Where Upside Down Is Right Side Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WRCU-14-22466 WU Catalog Covers 2015.Indd

2015Summer Semester MAY THROUGH AUGUST Courses FACULTY DAY AND TIME LOCATION AAUW Morning Book Tuesday, May 26 at Jean Weiker 10th Floor Lounge Group 9:30a.m. Be a part of this monthly book discussion group. It's open to any Bridgeport Area Branch member. If you would like to come to the meeting as a visitor, perhaps you will like the experience and decide to join AAUW. *If you are not a resident and you are interested in joining this group please contact Jean Weiker at 203-916-8305. A Child in a Japanese POW Tuesday, August 25 Marjolijn de Jager Auditorium Camp WWII at 1:30p.m. Join Marjolijn as she provides an insiders look at life as a child in a Japanese POW Camp. There will be discussions followed by the documentary, Song of Survival . Anatomy of a Car: What's Wednesday, June 24 Ivan Santiago Health Center Parking Lot Under The Hood at 2p.m. Join experienced driver and car enthusiast Ivan for an insiders look at cars. Learn about what goes into making and maintaining a car. Aqua Zumba Cindy McGuire Mondays, 10:30a.m. Fitness Center Zumba is one of the hottest fitness trends...and we're taking these dance moves to the pool! This class integrates the Zumba formula and philosophy with traditional aqua fitness. Join us for splashing, stretching, twisting, and even shouting and laughing. Sign up in the fitness center. For $30 you will be registered for 10 classes. *Must be Fitness Center Member to participate. Wednesday, May 27 Art Reception Sue Chrien Art Group Art Gallery at 2p.m. -

Believe: the Music of Cher Seattle Men's Chorus Encore Arts Seattle

MARCH 2019 the music of MARCH 30 & 31 | ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PAUL CALDWELL | SEATTLECHORUSES.ORG With the nation’s premier Cher impersonator and winner of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars, CHAD MICHAELS BYLANDBYSEA BYEXPERTS With unmatched experience and insider knowledge, we are the Alaska experts. No other cruise line gives you more options to see Glacier Bay. Plus, only we give you the premier Denali National Park adventure at our own McKinley Chalet Resort combined with access to the majestic Yukon Territory. It’s clear, there’s no better way to see Alaska than with Holland America Line. Call your Travel Advisor or 1-877-SAIL HAL, or visit hollandamerica.com Ships’ Registry: The Netherlands HAL 14038-4 Alaska4up_SeattleChorus_V1.indd 1 2/12/19 5:04 PM Pub/s: Seattle Chorus Traffic: 2/12/19 Run Date: March Color: CMYK Author: SN Trim: 8.375"wx10.875"h Live: 7.375"w x 9.875"h Bleed: 8.625"w x 11.125"h Version#: 1 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR I’ve said it before: refrains of hate and division that fall Seattle takes queens on the ears of his students every day. very seriously. If This was an invitation to do something RuPaul is on TV, different, something bold, something you can’t get a really beautiful. seat at any of So every winter, I go to the school the Capitol Hill weekly. But I don’t go alone. Singers establishments. from Seattle Men’s and Women’s Everything is jam-packed. And the Choruses take off work to be there exuberance of the fans rivals that of with me at 8:55 every Thursday the 12th man at a Seahawks game. -

Concert Program Copy

AMERICAN LYRIC THEATER PRESENTS FROM ERASED TO SELF-EMPOWERED CELEBRATING BIPOC COMPOSERS AND LIBRETTISTS TEXTS AND TRANSLATIONS “O Viviane, auprès de toi” from Brocéliande (1892) Composer: Lucien Lambert (1858-1945) LibreDst: André Alexandre (1860-1928) GILDAS GILDAS O Viviane, auprès de toi l’heure trop brève O Viviane, the too brief hour, Dans un enchantement s’enfuit. In enchantment, has fled. Combien de fois le jour a remplacé la nuit How many Lmes has day replaced the night, Depuis qu’en ce château je rêve Since I dreamt, in this castle, De ton regard exquis et de ton front divin! Of your exquisite gaze and your divine face. Mais je dois regagner enfin but I have to go back Le palais de mon maître; To my master’s palace; O blonde charmeresse, O blonde charmer, Laisse moi parLr, le temps presse. me leave, Lme presses. VIVIANE VIVIANE J’ai marché ce=e nuit dans le bois merveilleux That night, I walked into the wonderful woods Où la source murmure à l’ombre des cyLses Where the spring whispers in the shades of the trees, Et les on des surprises And the all the wonders, M’ont demandé Asked me, ‘Pourquoi ces larmes dans tes yeux?’ ‘Why the tears in your eyes?’ J’ai répondu I responded, ‘Le mal d’aimerest chose étrange. ‘The evil of loving is a strange thing. Quand je voudrais sourire il me tombe des pleurs, When I want to smile, I fall into tears, Et mon être languit, mystérieux mélange And my being languishes, mysterious mixture De chansons d’allégresse et d’hymnes de douleurs.’ Of songs of joy and hymns of pain.’ Reste, Gildas, pour toi mes lèvres Stay Gildas, for you my lips Ont appris de charmants aveux; Have learned charming confessions; Nous vivrons d’éternelles fièvres, We will live in an eternal fever, De parfums et de songes bleus. -

Carl M. Szabo, General Counsel 1401 K St NW, Suite 502 Washington

NetChoice Promoting Convenience, Choice, and Commerce on The Net Carl M. Szabo, General Counsel 1401 K St NW, Suite 502 Washington, DC 20005 202-420-7485 www.netChoiCe.org May 15, 2018 Governor Larry Hogan State House 100 State CirCle Annapolis, MD 21401 - 1925 RE: Support for HB740/SB693, Ticket website domain names Dear Governor Hogan: We ask that you sign into law, HB740/SB693 as it will help proteCt Maryland residents from deCeptive and misleading concert and sports ticket website domains. Fans aCross Maryland regularly searCh online for tiCkets to their favorite ConCerts and shows. Unfortunately, many fans are misled by deCeptive domain names in searCh results, whiCh are designed to triCk fans into thinking they are seeing unsold seats offered by the venue. Take for example, a fan looking to see Cher in ConCert this weekend at the MGM theater at National Harbor. That fan enters “cher national harbor” in her searCh engine, and here’s the top result she sees: Despite the domain name, theaternationalharbor.com, this site has no affiliation with MGM National Harbor. In faCt, this website is run by a tiCket resale outfit that shows only tiCkets offered by brokers – at signifiCant markups over regular seats still available at National Harbor. The website theaternatioanlharbor.Com makes it appear they are the offiCial site for National Harbor, and displays SeCtion 3 seats for Saturday night’s show at over $400 (see image at right). But over at MGM’s offiCial tiCket website, there are still dozens of unsold seats in Section 3, at the face value of $270. -

32741-Memory-Folder.Pdf

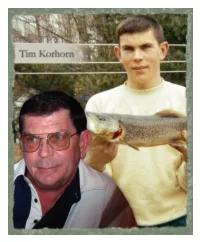

Tim Korhorn liked to keep his life simple, with his family at the center and his hunting and fi shing just a little off to the side. He was very happy to combine, spending a day with his family and fi shing together. The 1950s were a bustling, optimistic time in American history. Neighborhoods and schools were bursting at the seams in the post-war Baby Boom. Families moved from the cities to stake their claims on a comfortable life in the suburbs, where new domestic technologies promised to make the average American life easier. On the outskirts of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Egbert “Eggie” and Esther (Hulst) Korhorn were celebrating a “baby boom” of their own with the birth of their son, Timothy, on June 17, 1951. Tim grew up in Grand Rapids with his two sisters, Corrine and Nancy. His father provided well for the family as a District Manager at the Grand Rapids Press while his mother worked as a school cook and cared for their family. Tim received his education in the Kenowa Hills Public Schools and graduated in 1969. Already in high school, Tim developed a strong work ethic while working as a cook at Delight Restaurant in Standale. However, after graduating, he focused on his future and enrolled in trade school to learn the skills of a tool and die maker. In 1971 - he met the love of his life, Sharlene “Shar” Buhrer, while bowling at Allendale Lanes. The two began dating and fell hopelessly in love. They were happily married a year later in the Allendale Christian Reformed Church on October 7, 1972. -

Index 1994–2009 (Volumes 1–16)

THE GAY & LESBIAN REVIEW / WORLDWIDE Formerly: THE HARVARD GAY & LESBIAN REVIEW (1994-1999) INDEX 1994–2009 (VOLUMES 1–16) FEATURE ARTICLES “ACHIEVING FAILURE” (gallery show). SEE Arning 7:1 “Corpus Christi” (play). SEE Frontain 14:2 “DOWN LOW” SEE Boykin. 12.6 “EX-GAY MOVEMENT” SEE Grizzle 9:1 “Ex-Gay.” See Toscano. 16:3 “EX-GAYS” (movement). SEE Khan 7:3, Pietrzyk 7:3 “EX-GAYS” SEE Benjamin. 12.6 “FIELD, MICHAEL.” SEE Bergman. 6:3 “FINE BY ME” (slogan) SEE Huff-Hannon. 12.3 “Fireworks” (movie) SEE Anger interview 14:2 “GAY GENE.” SEE Rosario 10:6 “Gendercator” (movie). SEE White 14:5 “Giovanni’s Apartment.” SEE Woodhouse. 1:1 “HOMINTERN” [joke] SEE Woods.10:3 “HOMOSEXUAL BRAIN.” SEE Gallo 7:1 “QUEER” (LANGUAGE USAGE) SEE Paige 9:4 “REBECCA” (movie) SEE Greenhill. 14:3 “RICE QUEENS” See Nawrocki 9:2 “TADZIO” (character). SEE Adair. 10:6 “The Editors” Survey Says …. 12.1 “Times of Harvey Milk” (Film). SEE Herrera. 16:2 “Wat Niet Mag” (play). SEE Senelick 14:3 A PLACE AT THE TABLE (book) see Bergman 11:1 Aarons, Leroy F. SEE Stone. 13:1 ABRAMOFF, JACK. SEE Ireland. 13:2 ACTIVISM see Duberman 11:1, Schulman 11:1, Warren 11:1 ACTUP (ORGANIZATION). SEE Kramer. 2:3 Adair, Gilbert. The Real Tadzio of Thomas Mann. 10:6 Adelman, Marcy, interviewee. “Openhouse” Takes Root by the Bay. 14:1 ADVERTISING. SEE Joffe 14:5 AFGHANISTAN. SEE Baer.10:2 AFGHANISTAN. SEE Luongo, 15:2 AFRICAN AMERICAN GAY MEN. SEE Dang. 12.2 AFRICAN-AMERICAN CHURCHES. SEE Blaxton, 5:1 AFRICAN-AMERICAN LESBIAN LITERATURE. -

Commercial Tffeaiicr Wants to Thaw Things out the Most Immediate Way Is to Slide Government Costs 10 Percent Immediately

Minit-Ed * New Jersey was in the deep freeze as the new administration took office in Trenton. The hoopla now is over. Even the echoes have died away. Gov. Kean now, it is hoped, has his sleeves rolled up and is hammering away at his numerous problems. If he Commercial Tffeaiicr wants to thaw things out the most immediate way is to slide government costs 10 percent immediately. Howls of the Trenton disinherited would be lost among and SOUTH BERGEN REVIEW the cheers of the long suffering taxpayers. Why should government cost signs be on a one-way street marked UP? Come on, Tom Sharpen the knife. VOL. 60 NO. 27 OS„S,2!.,20 @ THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 1982 Prtfetatat251 Ridge Rd . Lyndhurst weewr.0^ ' N Grantsmen Attacked By Commissioner Guida By Amy Divine was so and submitted a list which $406,000 had been Commissioner-JUames of the work including approved Guida lashed out at Bruno much paperwork - done by When it was suggested Associates. Lyndhurst Bruno Associates in its ef that Mayor Joseph grantsmen. during the forts to obtain whatever Carucci s othce nught work meeting last Tuesday government funds art- work on obtaining grants night. available for various pro he said. Getting grants is jects of the community- In in my department but 1 Guida told the firms several attempts, the haven't enough personnel representative. William township did not qualify JKatterman. that though to do all the paperwork for the funds applied for. the company states it has necessary to apply for all as noted in the report the grants we would like achieved several grants for the township he has not Guida said he was not John Bruno has be'-n seen any funds sent to the denigrating Katterman s notified by the board that town s treasury as yet He work jut still saw little sol his contract with the town further contended that the id results in the form of ship will expire on March funds for several street money. -

Funone Activities 2019 Individuals Name: ______

FunOne Activities 2019 Individuals Name: ____________________________________________________ Individuals Address: ____________________________________________________________ Individuals City: ______________________________ Home’s Phone #: __________________ Home Manager: _____________________________ Managers Cell#: ____________________ Listed below are activities that are planned so far for 2019. Please look over the list of days and times. All of these activities will be 1individual to 1 staff. Just because you sign up for an activity does not mean that you will be doing the activity. FunOne needs to serve multiple people. The cost will be worked out between the Manager and the FunOne Administrator. The manager will need to put the activity on the home calendar and plan for the individual to attend. The FunOne Administrator and Home Manager will work with Teri to assure any medications that the individual has to taken will be given appropriately. The manager can encourage and suggest the staff person to work with the individual going on the trip, but final decision will be made by the FunOne Administrator. The activities below are ones that are planned for 2019, but we are not limited to just these activities. If you have an individual who wants to do something without the entire home, please email me to let me what they would like to do. Furthermore, as more activities come available in 2019, I will be giving out additional list at the Administrative Staff Meeting. Please fill out this form completely. Please put a checkmark beside the activities that the individual would like to be considered for to attend. You can either email it back to me or put it in my mailbox at Choices. -

2003 Calendar of Events January

2003 Calendar of Events January 3-5 – Kroger/Valleydale Championship Rodeo – Salem Civic Center, 540-375-3004, www.salemciviccenter.com. 5 – Smith Mountain Lake State Park Lecture Series – 3 pm. The History of Smith Mountain Lake and Dam. $. 540-297-6066. 10 – Free Friday at Science Museum of Virginia – 1-4 pm. 540-342-5710. 10 – Free Friday at Art Museum of Western Virginia – noon – 5 pm. 540-342- 5760. 20 – Free Friday at History Museum of Western Virginia – 540-342-5770. 10-11- Budweiser Monster Truck Challenge & Thrill Show - Salem Civic Center, 540-375-3004, www.salemciviccenter.com. 11 – Eastern National Draft Horse Pull – Virginia Horse Center, Lexington, 540-464- 2950. 11 – “Winnie the Pooh”. 10:30 am, 1:30 pm. Lynchburg Fine Arts Museum. 434-846- 8451. 13-Feb 22 – Chairs: On and Off the Wall – Exhibit 9-5. Lynchburg Fine Arts Center. Monday-Saturday, 434-846-8451. 14-19 – The Woman Who Amuses Herself – Waldron Stage, Mill Mountain Theatre, 540-342-5740. 17 – Lee-Jackson Day at Bedford City/County Museum – Newly designed Confederate Room opens, photo enhancements, restorations and repairs done on premises and costumed volunteers. 540-586-4520. 17–19 – Children’s Winter Carnival – Enjoy the sights and sounds of a real carnival in 1 the middle of winter, a completely indoor event. Call for times and ride prices. Salem Civic Center, 540-375-3004, www.salemciviccenter.com. 18 – Terri Allard in Concert – 7:30 p.m. Bedford Central Library. Country/Folk/Acoustic Pop. 540-586-8911, ext. 18, www.friendsofbedfordlibrary.org. 18 – Mark O’Connor at the Jefferson Center – 8:00 pm. -

Exotic Dance Clubs on Carpet

24 — THE HERALD. Wed., March 4, 1981 I Olender raps wrecker plan VERNON — Michael Olender, a reluctant for the three-mile limit provision., He said he allowed to join the association the following member of the Vernon Wrecker Owners feels it opens the town to a discretionary suit March but he claimed incurred damages Association, told the Town Council Monday by someone who might be 3.1 miles away. He from Feb. 1974 to March 1975. The chief’s night that he doesn't feel a recent proposal of jsaid he questions what wrecker owners in proposal at that time only allowed wrecker the police chief gives local towers a fair South Windsor and Bolton might do. “I feel the services within the town, willing to provide 24- shake. chief’s proposal will open a can of worms," he hour service, to belong to the association. The College basketball State Democrats Column reveals Doctors rewrite Olender, of Olender’s Inc. of Route 83, said said. court ruled that the town’s action wasn’t out of Resident proposes line. tourneys start suggest new tax I Cuban espionage the first he knew of the proposal of Police The council was supposed to discuss the freezing theory Chief Herman Fritz was when he read it in the proposal Monday night but the chief asked for Olender said it was his interpretation that a delay because a meeting he had scheduled Page 15 Page 8 Page 10 Page 20 newspapers. The chief's proposal would allow the courts gave the police department the for last week had to be postponed. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 4-3-1990 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1990). The George-Anne. 1169. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/1169 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Kerns to join Big East Conference SeePage 13B * 912/681-5246 Tuesday April 3,1°90 Since 1927, Georgia Southern's Official Student Newspaper Georgia Southern College • Statesboro, GA 30460 Brother Jim enrolls at GSC. pledges KA the KA's I don't know what I would By TONE LOC ful beings said he decided the at- not be so bad after all," said Brother "Now that I am here on only place to be," said Brother Jim. Staff Writer mosphere at GSC wasn't so bad Jim as his KA big brother Guido Southern's campus I am learning have done with my life. The life of an He then wiped drool from his mouth The Reverend Jim Gilles, better after all. guided him through the pledging how to live among the people and lie evangelist is a monotonous one and apparantly caused by the previous known as Brother Jim, has enrolled "If you can't beat 'em, join 'em," process. -

Overview the Ecosystem Surrounding the Sale and Use of Event Tickets Is More Complex Than Most Know

NetChoice Promoting Convenience, Choice, and Commerce on the Net Steve DelBianco, President Carl Szabo, Vice-President & General Counsel NetChoice 1401 K St NW, Suite 502 Washington, DC 20005 www.netchoice.org 202-420-7498 December 3, 2018 SUBMITTED ELECTRONICALLY Federal Trade Commission NetChoice Response to Federal Trade Commission Request for Request for Comments on FTC to Hold ) Workshop Examining Online Event Ticket Sale - Agency Seeks Input in Advance of March 2019 Workshop; Project No. P18450 ) NetChoice submits this response regarding the Federal Trade Commission’s (“FTC”) request for comments on the online event-ticket marketplace, FTC to Hold Workshop Examining Online Event Ticket Sale - Agency Seeks Input in Advance of March 2019 Workshop; Project No. P18450. NetChoice is a trade association of leading e-commerce and online companies promoting the value, convenience, and choice of internet business models. Our mission is to make the internet safe for free enterprise and for free expression. We work to promote the integrity and availability of the global internet and are significantly engaged in privacy issues in the states, in Washington, and in international internet governance organizations. Overview The ecosystem surrounding the sale and use of event tickets is more complex than most know. With a majority of tickets held-back from public sale for many events, and one company controlling a majority of primary tickets issued, the event ticket world is an area that the FTC can and should engage to ensure transparency, choice, and competition for all. The advent of online secondary ticket sales has made ticket purchases safer and more reliable.