Population Project: Municipal-Level Service Delivery in Labrador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Inuit

TOPIC 6.5 When Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation in 1949, whose responsibility was it to make provisions for Aboriginals? Will modern technology help or hinder Aboriginal groups in the preservation of their culture? 6.94 School children in front of the Grenfell Mission plane, Nain, 1966 Introduction When Newfoundland and Labrador joined and other services to Inuit communities. But unlike Confederation in 1949, the Terms of Union between the Moravians, who tried to preserve Inuit language the two governments made no reference to Aboriginal and culture, early government programs were not peoples and no provisions were made to safeguard their concerned with these matters. Teachers, for example, land or culture. No bands or reserves existed in the new delivered lessons in English, and most health and province and its Aboriginal peoples did not become other workers could not speak Inuktitut. registered under the federal Indian Act. Schooling, which was compulsory for children, had a Inuit huge influence on Inuit culture. The curriculum taught At the time of Confederation, at least 700 Inuit lived students nothing about their culture or their language, so in Labrador. Aside from their widespread conversion both were severely eroded. Many dropped out of school. to Christianity, many aspects of Inuit culture were Furthermore, young Inuit who were in school in their intact – many Inuit still spoke Inuktitut, lived on formative years did not have the opportunity to learn their traditional lands, and maintained a seasonal the skills to live the traditional lifestyle of their parents subsistence economy that consisted largely of hunting and grandparents and became estranged from this way and fishing. -

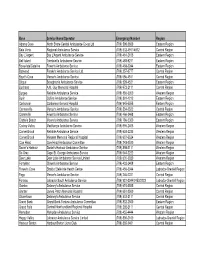

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Innu-Aimun Legal Terms Kaueueshtakanit Aimuna

INNU-AIMUN LEGAL TERMS (criminal law) KAUEUESHTAKANIT AIMUNA Sheshatshiu Dialect FIRST EDITION, 2007 www.innu-aimun.ca Innu-aimun Legal Terms (Criminal Law) Kaueueshtakanit innu-aimuna Sheshatshiu Dialect Editors / Ka aiatashtaht mashinaikannu Marguerite MacKenzie Kristen O’Keefe Innu collaborators / Innuat ka uauitshiaushiht Anniette Bartmann Mary Pia Benuen George Gregoire Thomas Michel Anne Rich Audrey Snow Francesca Snow Elizabeth Williams Legal collaborators / Kaimishiht ka uitshi-atussemaht Garrett O’Brien Jason Edwards DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE GOVERNMENT OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR St. John’s, Canada Published by: Department of Justice Government of Newfoundland and Labrador St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada First edition, 2007 Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-55146-328-5 Information contained in this document is available for personal and public non-commercial use and may be reproduced, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the Department of Justice, Newfoundland and Labrador. We ask only that: 1. users exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the material reproduced; 2. the Department of Justice, Newfoundland and Labrador be identified as the source department; 3. the reproduction is not represented as an official version of the materials reproduced, nor as having been made in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Department of Justice, Newfoundland and Labrador. Cover design by Andrea Jackson Printing Services by Memorial University of Newfoundland Foreword Access to justice is a cornerstone in our justice system. But it is important to remember that access has a broad meaning and it means much more than physical facilities. One of the key considerations in delivering justice services in Inuit and Innu communities is improving access through the use of appropriate language services. -

NEWFOUNDLAND and LABRADOR COLLEGE of OPTOMETRISTS Box 23085, Churchill Park, St

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR COLLEGE OF OPTOMETRISTS Box 23085, Churchill Park, St. John's, NL A1B 4J9 Following are the names of Optometrists registered with the Newfoundland and Labrador College of Optometrists as of 1 January 2014 who hold a therapeutic drug certificate and may prescribe a limited number of medications as outlined in the following regulation: http://www.assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/Regulations/rc120090.htm#3_ DR. ALPHONSUS A. BALLARD, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. JONATHAN BENSE, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GARRY C. BEST, GANDER, NL DR. JUSTIN BOULAY, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. LUC F. BOULAY, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. RICHARD A. BUCHANAN, SPRINGDALE, NL DR. ALISON CAIGER-WATSON, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. JOHN M. CASHIN, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GEORGE COLBOURNE, CORNER BROOK, NL DR. DOUGLAS COTE, PORT AUX BASQUES, NL DR. CECIL J. DUNCAN, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. CARL DURAND, CORNER BROOK, NL DR. RACHEL GARDINER, GOULDS, NL DR. CLARE HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. DEAN P. HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. DEBORA HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. KEVIN HALLERAN, MOUNT PEARL, NL DR. ELSIE K. HARRIS, STEPHENVILLE, NL DR. JESSICA HEAD, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL 1 of 3 DR. IAN HENDERSON, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. PAUL HISCOCK, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. LISA HOUNSELL, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. RICHARD J. HOWLETT, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. SARAH HUTCHENS, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GRACE HWANG, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. PATRICK KEAN, BAY ROBERTS, NL DR. NADINE KIELLEY, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. CHRISTIE LAW, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. ANGELA MacDONALD, SYDNEY, NS DR. -

Iron Ore Company of Canada New Explosives Facility, Labrador City

IRON ORE COMPANY OF CANADA NEW EXPLOSIVES FACILITY, LABRADOR CITY Environmental Assessment Registration Pursuant to the Newfoundland & Labrador Environmental Protection Act (Part X) Submitted by: Iron Ore Company of Canada 2 Avalon Drive Labrador City, Newfoundland & Labrador A2V 2Y6 Canada Prepared with the assistance of: GEMTEC Consulting Engineers and Scientists Limited 10 Maverick Place Paradise, NL A1L 0J1 Canada May 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 1.1 Proponent Information ...............................................................................................3 1.2 Rationale for the Undertaking .................................................................................... 5 1.3 Environmental Assessment Process and Requirements ............................................ 7 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ..............................................................................................8 2.1 Geographic Location ..................................................................................................8 2.2 Land Tenure ............................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Alternatives to the Project ........................................................................................ 10 2.4 Project Components ................................................................................................ 10 2.4.1 Demolition and -

Rapport Rectoverso

HOWSE MINERALS LIMITED HOWSE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT – (APRIL 2016) - SUBMITTED TO THE CEAA 11 LITERATURE CITED AND PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS Personal Communications André, D., Environmental Coordinator, MLJ, September 24 2014 Bouchard, J., Sécurité du Québec Director, Schefferville, September 26 2014 Cloutier, P., physician in NNK, NIMLJ and Schefferville, September 24 2014 Coggan, C. Atmacinta, Economy and Employment – NNK, 2013 and 2014 (for validation) Corbeil, G., NNK Public Works, October 28 2014 Cordova, O., TSH Director, November 3 2014 Côté, S.D., Localization of George River Caribou Herd Radio-Collared Individuals, Map dating from 2014- 12-08 from Caribou Ungava Einish, L., Centre de la petite enfance Uatikuss, September 23 2015 Elders, NNK, September 26 2014 Elders, NIMLJ, September 25 2014 Fortin, C., Caribou data, December 15 2014 and January 22 2014 Gaudreault, D., Nurse at the CLSC Naskapi, September 25 2014 Guanish, G., NNK Environmental Coordinator, September 22 2014 ITUM, Louis (Sylvestre) Mackenzie family trapline holder, 207 ITUM, Jean-Marie Mackenzie family, trapline holder, 211 Jean-Hairet, T., Nurse at the dispensary of Matimekush, personal communication, September 26 2014 Jean-Pierre, D., School Principal, MLJ, September 24 2014 Joncas, P., Administrator, Schefferville, September 22 2014 Lalonde, D., AECOM Project Manager, Environment, Montreal, November 10 2015 Lévesque, S., Non-Aboriginal harvester, Schefferville, September 25 2014 Lavoie, V., Director, Société de développement économique montagnaise, November 3 2014 Mackenzie, M., Chief, ITUM, November 3 2014 MacKenzie, R., Chief, Matimekush Lac-John, September 23 and 24 2014 Malec, M., ITUM Police Force, November 5 2014 Martin, D., Naskapi Police Force Chief, September 25 2014 Michel, A. -

Eastern Labrador Field Excursion for Explorationists

EASTERN LABRADOR FIELD EXCURSION FOR EXPLORATIONISTS Charles F. Gower Geological Survey, Department of Natural Resources, Newfoundland and Labrador, P.O. Box 8700, St. John’s, Newfoundland, A1B 4J6. with contributions from James Haley and Chris Moran Search Minerals Inc., Suite 1320, 855 West Georgia St., Vancouver, B.C., V6C 3E8 and Alex Chafe Silver Spruce Resources Inc., Suite 312 – 197 Dufferin Street, Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, B4V 2G9. Open File LAB/1583 St. John’s, Newfoundland September, 2011 NOTE Open File reports and maps issued by the Geological Survey Division of the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources are made available for public use. They have not been formally edited or peer reviewed, and are based upon preliminary data and evaluation. The purchaser agrees not to provide a digital reproduction or copy of this product to a third party. Derivative products should acknowledge the source of the data. DISCLAIMER The Geological Survey, a division of the Department of Natural Resources (the “authors and publish- ers”), retains the sole right to the original data and information found in any product produced. The authors and publishers assume no legal liability or responsibility for any alterations, changes or misrep- resentations made by third parties with respect to these products or the original data. Furthermore, the Geological Survey assumes no liability with respect to digital reproductions or copies of original prod- ucts or for derivative products made by third parties. Please consult with the Geological Survey in order to ensure originality and correctness of data and/or products. Recommended citation: Gower, C.F., Haley, J., Moran, C. -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

(PL-557) for NPA 879 to Overlay NPA

Number: PL- 557 Date: 20 January 2021 From: Canadian Numbering Administrator (CNA) Subject: NPA 879 to Overlay NPA 709 (Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada) Related Previous Planning Letters: PL-503, PL-514, PL-521 _____________________________________________________________________ This Planning Letter supersedes all previous Planning Letters related to NPA Relief Planning for NPA 709 (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada). In Telecom Decision CRTC 2021-13, dated 18 January 2021, Indefinite deferral of relief for area code 709 in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) approved an NPA 709 Relief Planning Committee’s report which recommended the indefinite deferral of implementation of overlay area code 879 to provide relief to area code 709 until it re-enters the relief planning window. Accordingly, the relief date of 20 May 2022, which was identified in Planning Letter 521, has been postponed indefinitely. The relief method (Distributed Overlay) and new area code 879 will be implemented when relief is required. Background Information: In Telecom Decision CRTC 2017-35, dated 2 February 2017, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) directed that relief for Newfoundland and Labrador area code 709 be provided through a Distributed Overlay using new area code 879. The new area code 879 has been assigned by the North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) and will be implemented as a Distributed Overlay over the geographic area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador currently served by the 709 area code. The area code 709 consists of 211 Exchange Areas serving the province of Newfoundland and Labrador which includes the major communities of Corner Brook, Gander, Grand Falls, Happy Valley – Goose Bay, Labrador City – Wabush, Marystown and St. -

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush Benefits of Labrador West Established community = reduced start up costs for industry Suited for operation phase of projects Experience of labour force Resource companies share in the value of creating community through corporate stewardship. Community amenities key for retaining workers. Link to natural environment – recreation amenities. Boom Bust Cycle Last big Bust 1982 Hundreds of homes vacant for approx 8 yrs Homes sold by banks and companies for $5,000- $25,000 Affordable homes and affordable apartment rents until 2005 2010 – same homes sell for $325,000 - $549,000 rental rates now $1,000 per bedroom i.e. 1 bedroom apt 1,200, 2 bedroom $2,000 and house rental $5,000 month! Challenges of Labrador West • Economic dependence on single industry • Growth impaired due to subsurface mineral rights • Transient Workforce Population • Expense of building/operating in remote northern location Challenges: Single Industry Market is volatile Community grows and diminishes in response to the resource Non renewable = finite. Challenges: Growth • Expansion/development encroach on mineral reserves • Land management strongly influenced by Provincial interest and local industry • Growth responds to market conditions – often lags behind needs of community and industry Challenges: Flyin/Flyout Arrangements Necessary for resource projects when workforce needs are high but short lived. I.e. construction phase Transient residents – not fully engaged in community (i.e. lack of community involvement and volunteerism. Often project negative image of the region due to their lived reality.) Negative perception amongst long-term residents of “contractors”. -

Carol Inn Listing Flyer.Indd

HOTEL INVESTMENT PROPERTY CAROL INN 215 Drake Avenue, Labrador City, NL HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY CBRE, as the exclusive advisor to PwC, is pleased to present for sale the Carol Inn (the “Hotel” or “Property”). ROB COLEMAN +1 709 754 1454 Offi ce The Carol Inn is located within the Central Business District of Labrador City with high visibility via Drake Avenue. The hotel is +1 709 693 3868 Cell approximately 4.7 kilometers north of the Wabush Airport. [email protected] Strategically located within Lab West, the property features visibilty from the Trans-Labrador Highway, allowing for easy access to all high LLOYD NASH volume roads within the community. +1 709 754 0082 Offi ce +1 709 699 7508 Cell The Hotel has a total of 22 guest rooms, offering a mix of room types to meet leisure, corporate, and extended-stay demand. Signifi cant [email protected] rennovations have been undertaken in recent years to the hotel. The Property also contains basement meeting rooms, main level bar, 140 Water Street, Suite 705 dining room and restaurant. Oppotunities exist for redevelopment, of St. John`s, NL A1C 6H6 those areas currently not in operation. Fax +1 709 754 1455 This property has abundant parking and the potential for expansion. This unique opportunity rarely comes to market in Lab West - a rare commercial building, strategically located in the heart of Lab West. HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY INVESTMENT PROFILE | CAROL INN INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS STRONG LOCATION The Carol Inn is located in Labrador City, on the mainland portion of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

Hearing Aid Providers (Including Audiologists)

Hearing Aid Providers (including Audiologists) Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 16 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2R6 1-709-489-8500 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-489-8497 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioners: Joanne Hunter, Jodine Reid Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 3 Herald Avenue Corner Brook, NL A2H 4B8 1-709-639-8501 (Corner Brook) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-639-8502 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioner: Jason Gedge Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Hearing Service 3 Paton Street St. John’s, NL A1B 4S8 1-709-726-8083 (St. John’s) 1-800-563-8083 (Toll free) 1-709-726-8111 (Fax) [email protected] www.beltone.nl.ca Audiologists: Brittany Green Hearing Aid Practitioners: Mike Edwards, David King, Kim King, Joe Lynch, Lori Mercer Satellite Locations: Bay Roberts, Bonavista, Carbonear, Clarenville, Gander, Grand Bank, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador City, Lewisporte, Marystown, New-Wes- Valley, Twillingate ________________________________ Exploits Hearing Aid Centre 9 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2S8 1-709-489-8900 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-800-563-8901 (Toll free) 1-709-489-9006 (Fax) [email protected] www.exploitshearing.ca Hearing Aid Practitioners: Dianne Earle, William Earle, Toby Penney ________________________________ Maico Hearing Service 84 Thorburn Road St.