The Transition from the Migratory to the Resident Fishery in the Strait of Belle Isle*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

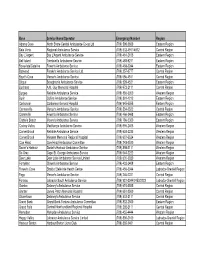

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

Eastern Labrador Field Excursion for Explorationists

EASTERN LABRADOR FIELD EXCURSION FOR EXPLORATIONISTS Charles F. Gower Geological Survey, Department of Natural Resources, Newfoundland and Labrador, P.O. Box 8700, St. John’s, Newfoundland, A1B 4J6. with contributions from James Haley and Chris Moran Search Minerals Inc., Suite 1320, 855 West Georgia St., Vancouver, B.C., V6C 3E8 and Alex Chafe Silver Spruce Resources Inc., Suite 312 – 197 Dufferin Street, Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, B4V 2G9. Open File LAB/1583 St. John’s, Newfoundland September, 2011 NOTE Open File reports and maps issued by the Geological Survey Division of the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources are made available for public use. They have not been formally edited or peer reviewed, and are based upon preliminary data and evaluation. The purchaser agrees not to provide a digital reproduction or copy of this product to a third party. Derivative products should acknowledge the source of the data. DISCLAIMER The Geological Survey, a division of the Department of Natural Resources (the “authors and publish- ers”), retains the sole right to the original data and information found in any product produced. The authors and publishers assume no legal liability or responsibility for any alterations, changes or misrep- resentations made by third parties with respect to these products or the original data. Furthermore, the Geological Survey assumes no liability with respect to digital reproductions or copies of original prod- ucts or for derivative products made by third parties. Please consult with the Geological Survey in order to ensure originality and correctness of data and/or products. Recommended citation: Gower, C.F., Haley, J., Moran, C. -

Fixed Link Between Labrador and Newfoundland Pre-Feasibility Study Final Report

Fixed Link between Labrador and Newfoundland Pre-feasibility Study Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................. 1 Background and Purpose ............................................ 1 Overview of Previous Work ......................................... 1 Other Relevant Fixed Links & Tunnels Worldwide .................... 1 The Environment and Geology of the Study Area ..................... 1 Assessment of Alternative Fixed Link Concepts ..................... 2 Bridge..............................................................2 Causeway............................................................2 Tunnels.............................................................2 Comparison Summary of Alternatives..................................3 Implementation Schedule ........................................... 4 Regulatory and Environmental Issues ............................... 4 Economic and Business Case Analysis ............................... 4 Financing Considerations .......................................... 7 Conclusions ....................................................... 7 1 INTRODUCTION................................................... 8 1.1 Background and Purpose....................................... 8 1.2 Overview of Previous Work.................................... 9 1.3 Study Approach.............................................. 10 2 REVIEW OF RELEVANT FIXED LINKS WORLDWIDE...................... 12 2.1 Øresund Link............................................... -

Innu Business Registry 27/03/2013

INNU BUSINESS REGISTRY 27/03/2013 REG NO ACCOMMODATION AND FOOD SERVICES PARTNER(S) CORE BUSINESS INNU PARTNER DATE Reg #064-IA Innu Atautshuap Ken Somers, 1. Convenience store - groceries Kurtis Somers, Jan. 17, 2005 Box 391, 40 McKenzie, Sheshatshiu, NL, A0P 1M0 Box 391, 40 McKenzie, Sheshatshiu, NL, 2. Transportation service Sheshatshiu, NL, A0P 1M0 Contact: Ken Somers, A0P 1M0 3. Taxi service Kenneth Somers Jr., P: 709-497-8451, Contact: Ken Somers, Sheshatshiu, NL, A0P 1M0 C:709-896-1802, P: 709-497-8451, Katrina Somers, F: 709-497-8120, C:709-896-1802, Sheshatshiu, NL, A0P 1M0 E: [email protected] F: 709-497-8120, E: [email protected] Reg #163-ICI International Catering Inc. Mene Conley, 1.Catering (including large camps) Max Penashue, Sept. 15, 2011 Box 211, Station C, 412 Lahr Blvd, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, NL, Box 211, Station C, 412 Lahr Blvd, Happy 2. Housekeeping Box 372, Sheshatshiu, NL, A0P 1M0 A0P 1C0 Valley-Goose Bay, NL, A0P 1C0 3. Janitorial C:709-899-2092, Contact: Mene Conley, Contact: Mene Conley, 4. Maintenance H: 497-8952, P: 709-896-4000, P: 709-896-4000, 4. Managerial services E: [email protected], C: 709-899-4004, C: 709-899-4004, 5. Commissionaires Service. F: 709-896-4747, F: 709-896-4747, 6. Catering to aircraft E: [email protected] E: [email protected] ESS Support Services (Compass Group Canada Ltd. and Komatik Support Service Inc.-JV) Contact: Brian Arbuckle, 2380 Bollard St., Lasalle, Quebec, H8N 1T2, P:514-761-5802, F: 514-761-1656, C: 514-831-1419, E: [email protected] Reg #005-LCLP Labrador Catering Limited Partnership East Coast Catering , 1.Catering (including large camps) INNU DEVELOPMENT LTD. -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

Rapport Rectoverso

HOWSE MINERALS LIMITED HOWSE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT – (APRIL 2016) - SUBMITTED TO THE CEAA 7.5 SOCIOECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT This document presents the results of the biophysical effects assessment in compliance with the federal and provincial guidelines. All results apply to both jurisdictions simultaneously, with the exception of the Air Quality component. For this, unless otherwise noted, the results presented/discussed refer to the federal guidelines. A unique subsection (7.3.2.2.2) is provided which presents the Air Quality results in compliance with the EPR guidelines. 7.5.1 Regional and Historical Context The nearest populations to the Project site are found in the Schefferville and Kawawachikamach areas. The Town of Schefferville and Matimekush-Lac John, an Innu community, are located approximately 25 km from the Howse Property, and 2 km from the Labrador border. The Naskapi community of Kawawachikamach is located about 15 km northeast of Schefferville, by road. In Labrador, the closest cities, Labrador City and Wabush, are located approximately 260 kilometres from the Schefferville area (Figure 7-37). The RSA for all socioeconomic components includes: . Labrador West (Labrador City and Wabush); and . the City of Sept-Îles, and Uashat and Mani-Utenam. As discussed in Chapter 4, however, Uashat and Mani-Utenam are considered within the LSA for land-use and harvesting activities (Section 7.5.2.1). The IN and NCC are also considered to be within the RSA, in particular due to their population and their Aboriginal rights and land-claims, of which an overview is presented. The section below describes in broad terms the socioeconomic and historic context of the region in which the Howse Project will be inserted. -

Canada's Last Frontier – the 1054Km Trans

TRAVEL TIMES ARE BASED ON POSTED SPEED LIMITS A new highway loop itinerary through Eastern Canada. New territories of unspoiled pristine wilderness and remote villages are yours to explore! The ultimate free-wheeling adventure. Halifax - Baie Comeau / 796km / 10h 40m / paved highway Routing will take you across the province of Nova Scotia, north through New Brunswick to a ferry crossing from Matane, QC (2h 15m) to Baie Comeau. Baie Comeau - Labrador West / 598km / 8h 10m / two-thirds paved highway Upgrading to this section of highway (Route 389) continues; as of the end of the summer of 2017, 434kms were paved. Work continues in 2018/19 on the remaining 167kms. New highway sections will open, one in 2018 and another in 2019; expect summer construction zones during this period. North from Baie Comeau Route 389 will take you pass the Daniel Johnson Dam, onward to the iron ore mining communities of Fermont, Labrador City and Wabush on the Quebec/Labrador border. Labrador West - Labrador Central / 533km / 7h 31m / paved highway Traveling east, all 533kms of Route 500 is paved (completed 2015). The highway affords you opportunities to view the majestic Smallwood reservoir and Churchill Falls Hydroelectric generating station on route to Happy Valley – Goose Bay, the “Hub of Labrador” and North West River for cultural exploration at the Labrador Interpretation Centre and the Labrador Heritage Society Museum. Happy Valley-Goose Bay is also the access point to travel to Nunatsiavut via ferry and air services or to the Torngat Mountains National Park. Central Labrador - Red Bay / 542km / 9h 29m / partially paved highway Going south on Route 510, you pass to the south of the Mealy Mountains and onward through sub- arctic terrain to the coastal communities of Port Hope Simpson and Mary’s Harbour, the gateway to Battle Harbour National Historic District. -

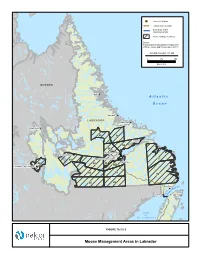

Moose Management Areas in Labrador !

"S Converter Station Transmission Corridor Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Moose Management Area Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_550 0 75 150 Kilometres QUEBEC Nain ! A t l a n t i c O c e a n Hopedale ! LABRADOR Makkovik ! Postville ! Schefferville! 85 56 Rigolet ! 55 54 North West River ! ! Churchill Falls Sheshatshiu ! Happy Valley-Goose Bay 57 51 ! ! Mud Lake 48 52 53 53A Labrador City / Wabush ! "S 60 59 58 50 49 Red Bay Isle ! elle f B o it a tr Forteau ! S St. Anthony ! G u l f o f St. Lawrence ! Sept-Îles! Portland Creek! Cat Arm FIGURE 10.3.5-2 Twillingate! ! Moose Management Areas in Labrador ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Port Hope Simpson ! Mary's Harbour ! LABRADOR "S Converter Station Red Bay QUEBEC ! Transmission Corridor ± Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Forteau ! 1 ! Large Game Management Areas St. Anthony 45 National Park 40 Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) 39 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_551 0 50 100 Kilometres 2 A t l a n t i c 3 O c e a n 14 4 G u l f 41 23 Deer Lake 15 22 o f ! 5 41 ! Gander St. Lawrence ! Grand Falls-Windsor ! 13 42 Corner Brook 7 24 16 21 6 12 27 29 43 17 Clarenville ! 47 28 8 20 11 18 25 29 26 34 9 ! St. John's 19 37 35 10 44 "S 30 Soldiers Pond 31 33 Channel-Port aux Basques ! ! Marystown 32 36 38 FIGURE 10.3.5-3 Moose and Black Bear Management Areas in Newfoundland Labrador‐Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 10 Existing Biophysical Environment Moose densities on the Island of Newfoundland are considerably higher than in Labrador, with densities ranging from a low of 0.11 moose/km2 in MMA 19 (1997 survey) to 6.82 moose/km2 in MMA 43 (1999) (Stantec 2010d). -

Mission for Labrador–Grenfell Health

Strategic Plan: 2008-2011 1 Message from the Chairperson In accordance with the Transparency and Accountability Act (SNL2004 Chapter T -8.1) and its reporting guidelines for Category 1 Entities, and on behalf of the Labrador-Grenfell Regional Health Authority (herein referred to as Labrador-Grenfell Health), I present the Authority’s Strategic Plan for 2008-11. This document summarizes the strategic directions that the health authority has committed to addressing over the next three years. This plan builds upon the successes achieved and lessons learned during the 2006-08 strategic planning cycle and also considers both the Department of Health and Community Services Strategic Directions (see Appendix A) and national health priorities. I am pleased to present specific goals, objectives and indicators for the following strategic initiatives: Child, Youth and Family Services; improved health status measurement tools; a culture of safety; fiscal and human resources capacity and regional health services planning. In accordance with the Section 5(4) of the Act, I, as do my fellow Board members, understand we are accountable for the preparation of this plan and for achieving the specific goals and objectives contained herein. Labrador-Grenfell Health looks forward to working together with its health and community partners in meeting the goals and objectives developed in this Strategic Plan. Respectfully, Larry Bradley Chair Labrador-Grenfell Regional Health Authority 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Overview page 4 2.0 Lines of Business page 5 3.0 Mandate page 9 4.0 Values page 10 5.0 Primary Clients page 11 6.0 Vision page 11 7.0 Mission Statement page 12 8.0 Strategic/Governance Issues page 15 Appendix A: Strategic Directions, DOHCS page 26 Appendix B: Board and Executive Office page 29 Appendix C: Facilities by Location page 30 Appendix D: Legislation and Regulations page 32 3 1.0 Overview Labrador-Grenfell Health provides quality health and community services to a population just under 37,000 and serves eighty-one communities. -

Labrador-Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement

Labrador-Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Plain Language Summary Stantec 2011 © Nalcor Energy has written this Plain Language Summary, in accordance with the Environmental Impact Statement Guidelines, to provide a short description of the transmission project and to describe how the transmission project will affect the environment. It also explains what Nalcor plans to do if it receives approval from the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the Government of Canada to build the transmission project. The summary is available in: English, French, Innu-aimun (Labrador and Quebec dialects), Naskapi and Inuktitut. For a more detailed and technical summary of the Environmental Impact Statement, please refer to the Executive Summary of the Environmental Impact Statement. Glossary of Terms Adaptive management – learning from experience and improving things like mitigation and processes to make them better. Alternating current (ac) – most common form of electrical current or power; this is the type of power that people use in their homes. Biophysical – physical and biological components of the environment, such as air quality, aquatics, wildlife on land and in water, etc. Converter station – equipment used to convert alternating current to direct current (or direct current back to alternating current). Converter stations are part of High Voltage direct current (HVdc) transmission systems. Direct current (dc) – direct current can be used to transmit power over long transmission lines to customers for their use. It must still be changed back to alternating current power before it’s delivered to people’s homes. Electrode – high capacity grounding system used to allow HVdc systems to still operate when one electrical conductor is out of service. -

Labrador-Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement

NALCOR ENERGY LABRADOR‐ISLAND TRANSMISSION LINK ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Chapter 3 Project Description April 2012 Labrador‐Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 3 Project Description TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................................. 3‐1 3.1 Project Overview ................................................................................................................................ 3‐1 5 3.2 Project Location ................................................................................................................................. 3‐3 3.3 Project Components and Layout ...................................................................................................... 3‐10 3.3.1 Muskrat Falls Converter Station ............................................................................................ 3‐10 3.3.2 Transmission Line ................................................................................................................. 3‐12 3.3.2.1 Muskrat Falls uto Fortea Point ........................................................................................ 3‐13 10 3.3.2.2 Strait of Belle Isle Submarine Cable Crossing ................................................................. 3‐25 3.3.2.3 Shoal Cove to Soldiers Pond ........................................................................................... 3‐28 3.3.3 Soldiers Pond Converter Station,