Labrador Census Data.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langelier Index Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland

Water Resources Langelier Index Summary for Public Water Supplies in Management Division Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Langelier Index Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well May 29, 2020 -1.06 Bay St. George South Highlands #3 Brian Pumphrey Well May 20, 2020 -0.29 Highlands Birchy Bay Birchy Bay Jumper's Pond May 06, 2020 -2.64 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond May 01, 2020 -1.77 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond May 19, 2020 -5.85 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond May 21, 2020 -3.64 Chance Cove Upper Cove Hollett's Well Jun 11, 2020 -2.17 Channel-Port aux Basques Channel-Port Aux Basques Gull Pond & Wilcox Pond May 20, 2020 -2.41 Clarenville Clarenville, Shoal Harbour Shoal Harbour River Jun 05, 2020 -2.23 Conception Bay South Conception Bay South Bay Bulls Big Pond May 28, 2020 -1.87 Corner Brook Corner Brook (+Massey Trout Pond, Third Pond (2 Jun 19, 2020 -1.88 Drive, +Mount Moriah) intakes) Fleur de Lys Fleur De Lys First Pond, Narrow Pond May 19, 2020 -3.41 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.65 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.54 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.33 Gander Gander Gander Lake May 25, 2020 -2.93 Gander Bay South Gander Bay South - PWDU Barry's Brook May 20, 2020 -4.98 Gander Bay South George's Point, Harris Point Barry's Brook May 20, 2020 -3.25 Grand Falls-Windsor Grand Falls-Windsor Northern Arm Lake Jun 01, 2020 -2.80 (+Bishop's Falls, +Wooddale, +Botwood, +Peterview) Grates Cove Grates Cove Centre #1C -

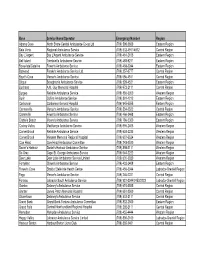

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Teaching & Learning Assistant Permanent Positions

Teaching & Learning Assistant Permanent Positions Amos Comenius Memorial School (Hopedale) J.R. Smallwood Memorial School (Wabush) Labrador Straits Academy (L’Anse Au Loup) Lake Melville School (North West River) Peacock Primary School (Happy Valley-Goose Bay) What is a TEACHING AND LEARNING ASSISTANT? The TLA is responsible for supporting teaching and learning in an inclusive environment in the areas of planning, instruction, social emotional learning, assessment, evaluation and collection of student data. Reporting to the Principal of the school the TLA will work with the classroom teacher to: ● Assist with the planning and organization of learning experiences for students in accordance with established policies and procedures. ● Assist the classroom teacher in implementing programs and services for students including the delivery of instructional supports. ● Assist the teacher in assessing, evaluating, reporting and recording student progress. ● Work collaboratively with the classroom teacher to develop supportive educational environments ● Participate as a member of school teams in meeting the needs of students. ● Maintain effective professional working relationships. Qualifications: Teacher’s Certificate Level Two (2) from the Registrar of Teacher Certification and Records at the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. How to obtain this Level 2 certification: Application form Educational requirements: Completion of a minimum of 20 courses (i.e. 60 credit hours) from Memorial University (or another approved university). Courses completed in the areas of Education, Social Sciences or Psychology will be considered an asset OR; minimum Level 2 Early Childhood Educator certification from the Association of Early Childhood Educators of Newfoundland and Labrador. Salary: Certificate Level Two (2) of the Teachers Salary Grid; $37,476 - $45,794 per annum Once certified apply to the NLESD Website Personnel Package for Teaching and Learning Assistant Vacant Positions. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

A GRAVITY SU VEY A ERN NOTR BAY, N W UNDLAND CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) HUGH G. Ml rt B. Sc. (HOI S.) ~- ··- 223870 A GRAVITY SURVEY OF EASTERN NOTRE DAME BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND by @ HUGH G. MILLER, B.Sc. {HCNS.) .. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Memorial University of Newfoundland. July 20, 1970 11 ABSTRACT A gravity survey was undertaken on the archipelago and adjacent coast of eastern Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. A total of 308 gravity stations were occupied with a mean station spacing of 2,5 km, and 9 gravity sub-bases were established. Elevations for the survey were determined by barometric and direct altimetry. The densities of rock samples collected from 223 sites were detenmined. A Bouguer anomaly map was obtained and a polynomial fitting technique was employed to determine the regional contribution to the total Bouguer anomaly field. Residual and regional maps based on a fifth order polynomial were obtained. Several programs were written for the IBM 360/40 computer used in this and model work. Three-dimensional model studies were carried out and a satisfactory overall fit to the total Bouguer field was obtained. Several shallow features of the anomaly maps were found to correlate well with surface bodies, i.e. granite or diorite bodies. Sedimentary rocks had little effect on the gravity field. The trace of the Luke's Arm fault was delineated. The following new features we r~ discovered: (1) A major structural discontinuity near Change Islands; (2) A layer of relatively high ·density (probably basic to ultrabasic rock) at 5 - 10 km depth. -

Lower Churchill Hydroelectric Generation Project: Community Health Study

Component Studies Socio-Economic Environment Socio-Economic Report 2 of 6 Community Health Study January 2009 Environmental Impact Statement for the Lower Churchill Hydroelectric Generation Project LOWER CHURCHILL HYDROELECTRIC GENERATION PROJECT: COMMUNITY HEALTH STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE REPORT LCP 535785 FINAL REPORT DECEMBER 22, 2008 Aura Environmental Research and Consulting Ltd. for Minaskuat Inc. Lower Churchill Hydroelectric Generation Project ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge Mark Shrimpton, Linda Jefferson and Colleen Leader with Minaskuat Inc. for providing study guidance and logistical support. We also acknowledge the following individuals for providing data and assistance with identifying key issues and health concerns pertinent to the communities and the region: • Doug Abbass (Principal, Peacock Primary School, Happy Valley-Goose Bay) • Dr. Maureen Baikie (Medical Officer of Health, Labrador Grenfell Health) • Andrew Battcock (Labrador School Board) • Carol Best (Labrador Central Economic Development Board) • Teresa Bruce (Retired Teacher, Sheshatshiu) • Delia Connell (Community and Aboriginal Affairs, Labrador-Grenfell) • Genevieve Corbin (Regional Director, Child Youth and Family Services) • Deanne Costello (Regional Director, Mental Health and Addictions Services) • Dolores Dooley (Program Consultant, Health and Community Services) • Blenda Dredge (Regional Director, Rehabilitation and Intervention Services) • Jan Dymond (Regional Director, Consumers’ Health Awareness Network Newfoundland and Labrador) • Nicole -

Eastern Labrador Field Excursion for Explorationists

EASTERN LABRADOR FIELD EXCURSION FOR EXPLORATIONISTS Charles F. Gower Geological Survey, Department of Natural Resources, Newfoundland and Labrador, P.O. Box 8700, St. John’s, Newfoundland, A1B 4J6. with contributions from James Haley and Chris Moran Search Minerals Inc., Suite 1320, 855 West Georgia St., Vancouver, B.C., V6C 3E8 and Alex Chafe Silver Spruce Resources Inc., Suite 312 – 197 Dufferin Street, Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, B4V 2G9. Open File LAB/1583 St. John’s, Newfoundland September, 2011 NOTE Open File reports and maps issued by the Geological Survey Division of the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources are made available for public use. They have not been formally edited or peer reviewed, and are based upon preliminary data and evaluation. The purchaser agrees not to provide a digital reproduction or copy of this product to a third party. Derivative products should acknowledge the source of the data. DISCLAIMER The Geological Survey, a division of the Department of Natural Resources (the “authors and publish- ers”), retains the sole right to the original data and information found in any product produced. The authors and publishers assume no legal liability or responsibility for any alterations, changes or misrep- resentations made by third parties with respect to these products or the original data. Furthermore, the Geological Survey assumes no liability with respect to digital reproductions or copies of original prod- ucts or for derivative products made by third parties. Please consult with the Geological Survey in order to ensure originality and correctness of data and/or products. Recommended citation: Gower, C.F., Haley, J., Moran, C. -

Ratepayers of Sheshatshui, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Wabush and Labrador City, for Intervenor Status in This Proceeding

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF PUBLIC UTILITIES 120 Torbay Road, P.O. Box 21040, St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, AlA 5B2 E-mail: [email protected] 2020-03-04 Senwung Luk Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP 250 University Ave, 8''* Floor Toronto, ON M5H3E5 Dear Sir: Re: Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro - Reliability and Resource Adequacy Study Review - Request for Intervenor Status The Board has reviewed the request of the Labrador Interconnected Group, representing the domestic ratepayers of Sheshatshui, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Wabush and Labrador City, for intervenor status in this proceeding. While acknowledging the request was submitted beyond the due date of January 17,2020 the Board accepts the explanation provided. The request indicates the Labrador Intercoimected Group is interested in all matters affecting or potentially affecting the Labrador Intercoimected system, including plaiming for power supply adequacy and reliability in Labrador and the treatment of the Island and Labrador Intercoimected systems as separate systems. The request indicates that the Labrador Interconnected Group intends to represent its clients only where their interests diverge from those of all ratepayers. The Board is satisfied that the communities represented by the Labrador Interconnected Group have a direct interest in the issues being considered in this proceeding insofar as these issues impact customers on the Labrador Interconnected system and that its participation as an intervenor may assist the Board in its understanding of these issues. The Labrador Interconnected Group will have limited standing in this review to represent the interests of Labrador Interconnected customers with respect to planning for power supply adequacy and reliability for the Labrador Interconnected system within the provincial electrical system. -

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush Benefits of Labrador West Established community = reduced start up costs for industry Suited for operation phase of projects Experience of labour force Resource companies share in the value of creating community through corporate stewardship. Community amenities key for retaining workers. Link to natural environment – recreation amenities. Boom Bust Cycle Last big Bust 1982 Hundreds of homes vacant for approx 8 yrs Homes sold by banks and companies for $5,000- $25,000 Affordable homes and affordable apartment rents until 2005 2010 – same homes sell for $325,000 - $549,000 rental rates now $1,000 per bedroom i.e. 1 bedroom apt 1,200, 2 bedroom $2,000 and house rental $5,000 month! Challenges of Labrador West • Economic dependence on single industry • Growth impaired due to subsurface mineral rights • Transient Workforce Population • Expense of building/operating in remote northern location Challenges: Single Industry Market is volatile Community grows and diminishes in response to the resource Non renewable = finite. Challenges: Growth • Expansion/development encroach on mineral reserves • Land management strongly influenced by Provincial interest and local industry • Growth responds to market conditions – often lags behind needs of community and industry Challenges: Flyin/Flyout Arrangements Necessary for resource projects when workforce needs are high but short lived. I.e. construction phase Transient residents – not fully engaged in community (i.e. lack of community involvement and volunteerism. Often project negative image of the region due to their lived reality.) Negative perception amongst long-term residents of “contractors”. -

Carol Inn Listing Flyer.Indd

HOTEL INVESTMENT PROPERTY CAROL INN 215 Drake Avenue, Labrador City, NL HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY CBRE, as the exclusive advisor to PwC, is pleased to present for sale the Carol Inn (the “Hotel” or “Property”). ROB COLEMAN +1 709 754 1454 Offi ce The Carol Inn is located within the Central Business District of Labrador City with high visibility via Drake Avenue. The hotel is +1 709 693 3868 Cell approximately 4.7 kilometers north of the Wabush Airport. [email protected] Strategically located within Lab West, the property features visibilty from the Trans-Labrador Highway, allowing for easy access to all high LLOYD NASH volume roads within the community. +1 709 754 0082 Offi ce +1 709 699 7508 Cell The Hotel has a total of 22 guest rooms, offering a mix of room types to meet leisure, corporate, and extended-stay demand. Signifi cant [email protected] rennovations have been undertaken in recent years to the hotel. The Property also contains basement meeting rooms, main level bar, 140 Water Street, Suite 705 dining room and restaurant. Oppotunities exist for redevelopment, of St. John`s, NL A1C 6H6 those areas currently not in operation. Fax +1 709 754 1455 This property has abundant parking and the potential for expansion. This unique opportunity rarely comes to market in Lab West - a rare commercial building, strategically located in the heart of Lab West. HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY INVESTMENT PROFILE | CAROL INN INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS STRONG LOCATION The Carol Inn is located in Labrador City, on the mainland portion of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

Execution Copy Wabush Iron Co. Limited

R-4 EXECUTION COPY WABUSH IRON CO. LIMITED - and - WABUSH RESOURCES INC. - and - WABUSH LAKE RAILWAY COMPANY LIMITED - and - TACORA RESOURCES INC. - and - MAGGLOBAL LLC ASSET PURCHASE AGREEMENT DATED AS OF JUNE 2, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ARTICLE 1 INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Definitions ...................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Actions on Non-Business Days......................................................................................16 1.3 Currency and Payment Obligations ...............................................................................17 1.4 Calculation of Time ........................................................................................................17 1.5 Tender ...........................................................................................................................17 1.6 Additional Rules of Interpretation ...................................................................................17 1.7 Schedules and Exhibits .................................................................................................18 ARTICLE 2 PURCHASE OF ASSETS AND ASSUMPTION OF LIABILITIES ......................... 18 2.1 Purchase and Sale of Purchased Assets .......................................................................18 2.2 Assumption of Assumed Liabilities ................................................................................19 -

HYDROGEOLOGY 50°0' Central Newfoundland

55°15' 55°0' 54°45' 54°30' 54°15' 54°0' 53°45' 53°30' 53°15' 50°15' Department of Environment and Conservation Department of Natural Resources Map No. 3b HYDROGEOLOGY 50°0' Central Newfoundland Well Yield Well Depth 50°0' Characteristics Characteristics (m) Number (L/min) Hydrostratigraphic Unit Lithology of Wells Average Median Average Median Unit 1 schist, gneiss, Low to Moderate Yield 73 20 6 51 48 quartzite, slate Metamorphic Strata siltstone, Unit 2 conglomerate, argillite, Low to Moderate Yield 1403 20 7 51 46 greywacke, with Sedimentary Strata minor volcanic 49°45' flows and tuff Unit 3 basic pillow Low to Moderate Yield lava, flows, 723 22 9 50 46 Barr'D Islands Volcanic Strata breccia and tuff 49°45' Fogo Joe Batt's Arm Tilting Unit 4 mafic and ultramafic Shoal Bay Pike's Arm Low Yield intrusions of ophiolite 13 9 7 58 61 Herring Neck Change Islands complexes FogoC oIsolkasn Pdond Ophiolite Complexes Durrell Deep Bay Fogo Island Region Unit 5 granite, granodiorite, Salt Harbour N o r t h Twillingate Island Harbour diabase, and diorite 688 22 9 44 37 Little Harbour Cobbs Arm A t l a n t i c Low to Moderate Yield Too Good Arm Seldom intrusions Notre Dame Bay O c e a n Plutonic Strata Gilliards Cove F Jenkins Cove rid Keattyle Cove Black Duck Cove Little Seldom Tizzard's Harbour B Rogers Cove ay Indian Cove Surficial deposits - Unconsolidated sediments Stag Harbour Newville Valley Pond Moreton's Harbour Surficial Hydrostratigraphic Units Fairbanks-Hillgrade Unit A - Till Deposits Hillgrade Port Albert Well yields range from 2 litres per minute (L/min) to 136 L/min and averaged 29 L/min Bridgeport 49°30' Virgin Arm-Carter's Cove with a median value of 18 L/min. -

The Transition from the Migratory to the Resident Fishery in the Strait of Belle Isle*

PATRICIA THORNTON The Transition from the Migratory to the Resident Fishery in the Strait of Belle Isle* THE EVOLUTION OF THE MERCHANT COLONIAL system in Newfoundland from migratory ship fishery to permanent resident fishery was a process which was repeated several times over the course of the colony's history, as frontier conditions retreated before the spread of settlement. On the east coast, the transition from a British-based shore fishery operated by hired servants to one in which merchants became suppliers and marketers for Newfoundland fishing families took place in the second half of the 18th century. Further north and on the south coast the migratory fishery persisted longer,1 but it was only in the Strait of Belle Isle that it held sway from its inception in the 1760s until well into the 1820s. Then here too it was slowly transformed into a resident fishery as migratory personnel became residents of the shore, with the arrival of settlers from Conception and Trinity Bays and merchants and traders from St John's and Halifax. Gerald Sider has provided an integrated and provocative conceptual framework within which to view this transformation. Three aspects of his thesis will be examined here. First, he states that the English merchants, controlling the migratory fishery throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, opposed permanent settlement and landed property. Second, he claims that in the face of settlement in the first four decades of the 19th century, the merchants reacted by getting out of the fishing business and entrapping the resident fishermen in a cashless truck system, a transition from wages to truck which, he claims, represented a loss to the fishermen and which had to be forcibly imposed by the courts.