Lower Churchill Hydroelectric Generation Project: Community Health Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching & Learning Assistant Permanent Positions

Teaching & Learning Assistant Permanent Positions Amos Comenius Memorial School (Hopedale) J.R. Smallwood Memorial School (Wabush) Labrador Straits Academy (L’Anse Au Loup) Lake Melville School (North West River) Peacock Primary School (Happy Valley-Goose Bay) What is a TEACHING AND LEARNING ASSISTANT? The TLA is responsible for supporting teaching and learning in an inclusive environment in the areas of planning, instruction, social emotional learning, assessment, evaluation and collection of student data. Reporting to the Principal of the school the TLA will work with the classroom teacher to: ● Assist with the planning and organization of learning experiences for students in accordance with established policies and procedures. ● Assist the classroom teacher in implementing programs and services for students including the delivery of instructional supports. ● Assist the teacher in assessing, evaluating, reporting and recording student progress. ● Work collaboratively with the classroom teacher to develop supportive educational environments ● Participate as a member of school teams in meeting the needs of students. ● Maintain effective professional working relationships. Qualifications: Teacher’s Certificate Level Two (2) from the Registrar of Teacher Certification and Records at the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. How to obtain this Level 2 certification: Application form Educational requirements: Completion of a minimum of 20 courses (i.e. 60 credit hours) from Memorial University (or another approved university). Courses completed in the areas of Education, Social Sciences or Psychology will be considered an asset OR; minimum Level 2 Early Childhood Educator certification from the Association of Early Childhood Educators of Newfoundland and Labrador. Salary: Certificate Level Two (2) of the Teachers Salary Grid; $37,476 - $45,794 per annum Once certified apply to the NLESD Website Personnel Package for Teaching and Learning Assistant Vacant Positions. -

Ratepayers of Sheshatshui, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Wabush and Labrador City, for Intervenor Status in This Proceeding

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF PUBLIC UTILITIES 120 Torbay Road, P.O. Box 21040, St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, AlA 5B2 E-mail: [email protected] 2020-03-04 Senwung Luk Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP 250 University Ave, 8''* Floor Toronto, ON M5H3E5 Dear Sir: Re: Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro - Reliability and Resource Adequacy Study Review - Request for Intervenor Status The Board has reviewed the request of the Labrador Interconnected Group, representing the domestic ratepayers of Sheshatshui, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Wabush and Labrador City, for intervenor status in this proceeding. While acknowledging the request was submitted beyond the due date of January 17,2020 the Board accepts the explanation provided. The request indicates the Labrador Intercoimected Group is interested in all matters affecting or potentially affecting the Labrador Intercoimected system, including plaiming for power supply adequacy and reliability in Labrador and the treatment of the Island and Labrador Intercoimected systems as separate systems. The request indicates that the Labrador Interconnected Group intends to represent its clients only where their interests diverge from those of all ratepayers. The Board is satisfied that the communities represented by the Labrador Interconnected Group have a direct interest in the issues being considered in this proceeding insofar as these issues impact customers on the Labrador Interconnected system and that its participation as an intervenor may assist the Board in its understanding of these issues. The Labrador Interconnected Group will have limited standing in this review to represent the interests of Labrador Interconnected customers with respect to planning for power supply adequacy and reliability for the Labrador Interconnected system within the provincial electrical system. -

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush Benefits of Labrador West Established community = reduced start up costs for industry Suited for operation phase of projects Experience of labour force Resource companies share in the value of creating community through corporate stewardship. Community amenities key for retaining workers. Link to natural environment – recreation amenities. Boom Bust Cycle Last big Bust 1982 Hundreds of homes vacant for approx 8 yrs Homes sold by banks and companies for $5,000- $25,000 Affordable homes and affordable apartment rents until 2005 2010 – same homes sell for $325,000 - $549,000 rental rates now $1,000 per bedroom i.e. 1 bedroom apt 1,200, 2 bedroom $2,000 and house rental $5,000 month! Challenges of Labrador West • Economic dependence on single industry • Growth impaired due to subsurface mineral rights • Transient Workforce Population • Expense of building/operating in remote northern location Challenges: Single Industry Market is volatile Community grows and diminishes in response to the resource Non renewable = finite. Challenges: Growth • Expansion/development encroach on mineral reserves • Land management strongly influenced by Provincial interest and local industry • Growth responds to market conditions – often lags behind needs of community and industry Challenges: Flyin/Flyout Arrangements Necessary for resource projects when workforce needs are high but short lived. I.e. construction phase Transient residents – not fully engaged in community (i.e. lack of community involvement and volunteerism. Often project negative image of the region due to their lived reality.) Negative perception amongst long-term residents of “contractors”. -

Carol Inn Listing Flyer.Indd

HOTEL INVESTMENT PROPERTY CAROL INN 215 Drake Avenue, Labrador City, NL HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY CBRE, as the exclusive advisor to PwC, is pleased to present for sale the Carol Inn (the “Hotel” or “Property”). ROB COLEMAN +1 709 754 1454 Offi ce The Carol Inn is located within the Central Business District of Labrador City with high visibility via Drake Avenue. The hotel is +1 709 693 3868 Cell approximately 4.7 kilometers north of the Wabush Airport. [email protected] Strategically located within Lab West, the property features visibilty from the Trans-Labrador Highway, allowing for easy access to all high LLOYD NASH volume roads within the community. +1 709 754 0082 Offi ce +1 709 699 7508 Cell The Hotel has a total of 22 guest rooms, offering a mix of room types to meet leisure, corporate, and extended-stay demand. Signifi cant [email protected] rennovations have been undertaken in recent years to the hotel. The Property also contains basement meeting rooms, main level bar, 140 Water Street, Suite 705 dining room and restaurant. Oppotunities exist for redevelopment, of St. John`s, NL A1C 6H6 those areas currently not in operation. Fax +1 709 754 1455 This property has abundant parking and the potential for expansion. This unique opportunity rarely comes to market in Lab West - a rare commercial building, strategically located in the heart of Lab West. HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY INVESTMENT PROFILE | CAROL INN INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS STRONG LOCATION The Carol Inn is located in Labrador City, on the mainland portion of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

Execution Copy Wabush Iron Co. Limited

R-4 EXECUTION COPY WABUSH IRON CO. LIMITED - and - WABUSH RESOURCES INC. - and - WABUSH LAKE RAILWAY COMPANY LIMITED - and - TACORA RESOURCES INC. - and - MAGGLOBAL LLC ASSET PURCHASE AGREEMENT DATED AS OF JUNE 2, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ARTICLE 1 INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Definitions ...................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Actions on Non-Business Days......................................................................................16 1.3 Currency and Payment Obligations ...............................................................................17 1.4 Calculation of Time ........................................................................................................17 1.5 Tender ...........................................................................................................................17 1.6 Additional Rules of Interpretation ...................................................................................17 1.7 Schedules and Exhibits .................................................................................................18 ARTICLE 2 PURCHASE OF ASSETS AND ASSUMPTION OF LIABILITIES ......................... 18 2.1 Purchase and Sale of Purchased Assets .......................................................................18 2.2 Assumption of Assumed Liabilities ................................................................................19 -

Rental Housing Portfolio March 2021.Xlsx

Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Private Sector Non Profit Adams Cove 1 1 Arnold's Cove 29 10 39 Avondale 3 3 Bareneed 1 1 Bay Bulls 1 1 10 12 Bay Roberts 4 15 19 Bay de Verde 1 1 Bell Island 90 10 16 116 Branch 1 1 Brigus 5 5 Brownsdale 1 1 Bryants Cove 1 1 Butlerville 8 8 Carbonear 26 4 31 10 28 99 Chapel Cove 1 1 Clarke's Beach 14 24 38 Colinet 2 2 Colliers 3 3 Come by Chance 3 3 Conception Bay South 36 8 14 3 16 77 Conception Harbour 8 8 Cupids 8 8 Cupids Crossing 1 1 Dildo 1 1 Dunville 11 1 12 Ferryland 6 6 Fox Harbour 1 1 Freshwater, P. Bay 8 8 Gaskiers 2 2 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Goobies 2 2 Goulds 8 4 12 Green's Harbour 2 2 Hant's Harbour 0 Harbour Grace 14 2 6 22 Harbour Main 1 1 Heart's Content 2 2 Heart's Delight 3 12 15 Heart's Desire 2 2 Holyrood 13 38 51 Islingston 2 2 Jerseyside 4 4 Kelligrews 24 24 Kilbride 1 24 25 Lower Island Cove 1 1 Makinsons 2 1 3 Marysvale 4 4 Mount Carmel-Mitchell's Brook 2 2 Mount Pearl 208 52 18 10 24 28 220 560 New Harbour 1 10 11 New Perlican 0 Norman's Cove-Long Cove 5 12 17 North River 4 1 5 O'Donnels 2 2 Ochre Pit Cove 1 1 Old Perlican 1 8 9 Paradise 4 14 4 22 Placentia 28 2 6 40 76 Point Lance 0 Port de Grave 0 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Portugal Cove/ St. -

The Labrador Trough

THE LABRADOR TROUGH: OPPORTUNITIES IN CANADA’S PREMIER IRON ORE DISTRICT Located in a modern, Labrador West politically stable, mining-friendly jurisdiction The Canadian provinces of NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR and QUEBEC Canada’s premier iron ore district Long production history: more than 60 years of profitable operations More than 2 thousand million tonnes produced Entry point into the seaborne market in Europe, Asia, the Middle East and N. America Opportunity for long-term reliability and competitively of future supply: no “Big 3” The Resource: World-class More than 80 billion tonnes of known iron ore resources with excellent exploration potential Near surface deposits; open pit mining methods Represents ca. 99.8% of Canadian production Most current and historic production by Rio Tinto-IOC (Carol Lake), Arcelor Mittal (Mont Wright, Fire Lake) and Cliffs Natural Resources (Bloom Lake, Wabush) Vastly underexplored on a district scale High-quality ores Low phosphorous, alumina, sulphur and alkalies High Fe content concentrate and pellets Superior quality relative to Australian and Brazilian product offsets freight disadvantage (for China markets) Product diversity: Lump, premium fines, concentrate and pellet grades Flexibility to deliver special products POWER INFRASTRUCTURE Ample water and reliable sources of low-cost hydro-electric power Stably priced green energy Key transportation infrastructure with excess rail and port capacity NEW INVESTMENTS IN MULTI-USER PORT FACILITIES PORT OF SEPT ISLES HANDLES CAPE-SIZE and CHINAMAX* VESSELS NO PROHIBITIVE CONTROL OF RAIL BY A MAJOR PRODUCER CANADIAN LAW RECOGNIZES THE QSN&L RAILWAY AS A “COMMON CARRIER” INVESTMENT POTENTIAL CURRENT “BEAR” MARKET HAS PROVIDED A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY TO CONSOLIDATE WITHIN THE DISTRICT Opportunities for future development: Labrador Northern Trough • NuTAC New Millennium Iron Corp. -

Labrador Mining and Power: How Much and Where From?

Labrador mining and power: how much and where from? Department of Natural Resources November 2012 Key Factors • $10-15 billion of investment in Labrador mining projects may be realized over the next decade but this is dependent in part on the availability and cost of power. • If these projects proceed they will bring major economic benefits to the province, through employment and taxation revenue (both direct and indirect), as well as provide opportunities for service industries. • Estimation of future power needs for planned mining developments is challenging, particularly as many projects have not advanced to the stage where firm requests for power have been made. • Based on projects already in construction or near sanction, existing generating capacity in Labrador may be exhausted by 2015-17. • Muskrat Falls could be an important source of power for mining developments post-2017, and sanctioning of the project may assist mining companies in making positive investment decisions. Availability of power will encourage investment in the province rather than in competing jurisdictions. • Muskrat Falls could provide power for future mining developments (or export markets if mining developments are slow to proceed) as well as providing sufficient power for the Island of Newfoundland. The Isolated Island option, with refurbishment or replacement of the Holyrood Generating Station or any other isolated alternative, will not supply the power needed for Labrador mining developments. • In the longer term, mining developments may absorb all residual power from the Muskrat Falls development. Further power may be needed. LABRADOR MINING AND POWER: HOW MUCH AND WHERE FROM? 1 Introduction The provincial minerals sector in 2012 is forecast to operate at record levels, with mineral shipments and mineral industry employment at all-time highs. -

Utilities Act, RSN 1990, Chapter P-47

IN THE MATTER OF, the Public Utilities Act, R.S.N. 1990, Chapter P-47 (the Act), and IN THE MATTER OF a General Rate Application (the Application) by Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro for approvals of, under Section 70 of the Act, changes in the rates to be charged for the supply of power and energy to Newfoundland Power, Rural Customers and Industrial Customers; and under Section 71 of the Act, Changes in the Rules and Regulations applicable to the Supply of electricity to Rural Customers. Requests for Information by the Towns of Labrador, Wabush, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, North West River (LWHN) 2 0 - 5 4 Issued: November 6, 2013 1 1. LWHN -NLH-20 Provide a table that gives the following: (1) 2. Labrador Interconnected System's share of the 3. rural deficit, expressed in dollars; (2) 4. Newfoundland Power's share of the rural deficits, 5. expressed in dollars, (3) the number of Labrador 6. Interconnected customers; (4) the number of NP 7. customers (or NL Hydro's best estimate 8. if it does not have exact figures); (5) based (1) and 9. (3), the Labrador Interconnected System's share 10. of the rural deficit per customer; and (6) based on 11. (2) and (4), NP's share of the rural deficit per NP 12. customer. The table should be for annual figures 13. from 2003 to the 2013 text year inclusive. Also, if 14. available, provide the forecasts for the years 2014 15. to 2017 inclusive. 16. LWHN-NLH-21 Please provide copies of the five most recent 17. -

Rapport Rectoverso

HOWSE MINERALS LIMITED HOWSE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT – (APRIL 2016) - SUBMITTED TO THE CEAA 7.5 SOCIOECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT This document presents the results of the biophysical effects assessment in compliance with the federal and provincial guidelines. All results apply to both jurisdictions simultaneously, with the exception of the Air Quality component. For this, unless otherwise noted, the results presented/discussed refer to the federal guidelines. A unique subsection (7.3.2.2.2) is provided which presents the Air Quality results in compliance with the EPR guidelines. 7.5.1 Regional and Historical Context The nearest populations to the Project site are found in the Schefferville and Kawawachikamach areas. The Town of Schefferville and Matimekush-Lac John, an Innu community, are located approximately 25 km from the Howse Property, and 2 km from the Labrador border. The Naskapi community of Kawawachikamach is located about 15 km northeast of Schefferville, by road. In Labrador, the closest cities, Labrador City and Wabush, are located approximately 260 kilometres from the Schefferville area (Figure 7-37). The RSA for all socioeconomic components includes: . Labrador West (Labrador City and Wabush); and . the City of Sept-Îles, and Uashat and Mani-Utenam. As discussed in Chapter 4, however, Uashat and Mani-Utenam are considered within the LSA for land-use and harvesting activities (Section 7.5.2.1). The IN and NCC are also considered to be within the RSA, in particular due to their population and their Aboriginal rights and land-claims, of which an overview is presented. The section below describes in broad terms the socioeconomic and historic context of the region in which the Howse Project will be inserted. -

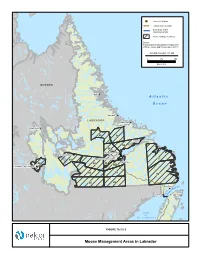

Moose Management Areas in Labrador !

"S Converter Station Transmission Corridor Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Moose Management Area Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_550 0 75 150 Kilometres QUEBEC Nain ! A t l a n t i c O c e a n Hopedale ! LABRADOR Makkovik ! Postville ! Schefferville! 85 56 Rigolet ! 55 54 North West River ! ! Churchill Falls Sheshatshiu ! Happy Valley-Goose Bay 57 51 ! ! Mud Lake 48 52 53 53A Labrador City / Wabush ! "S 60 59 58 50 49 Red Bay Isle ! elle f B o it a tr Forteau ! S St. Anthony ! G u l f o f St. Lawrence ! Sept-Îles! Portland Creek! Cat Arm FIGURE 10.3.5-2 Twillingate! ! Moose Management Areas in Labrador ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Port Hope Simpson ! Mary's Harbour ! LABRADOR "S Converter Station Red Bay QUEBEC ! Transmission Corridor ± Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Forteau ! 1 ! Large Game Management Areas St. Anthony 45 National Park 40 Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) 39 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_551 0 50 100 Kilometres 2 A t l a n t i c 3 O c e a n 14 4 G u l f 41 23 Deer Lake 15 22 o f ! 5 41 ! Gander St. Lawrence ! Grand Falls-Windsor ! 13 42 Corner Brook 7 24 16 21 6 12 27 29 43 17 Clarenville ! 47 28 8 20 11 18 25 29 26 34 9 ! St. John's 19 37 35 10 44 "S 30 Soldiers Pond 31 33 Channel-Port aux Basques ! ! Marystown 32 36 38 FIGURE 10.3.5-3 Moose and Black Bear Management Areas in Newfoundland Labrador‐Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 10 Existing Biophysical Environment Moose densities on the Island of Newfoundland are considerably higher than in Labrador, with densities ranging from a low of 0.11 moose/km2 in MMA 19 (1997 survey) to 6.82 moose/km2 in MMA 43 (1999) (Stantec 2010d). -

Lab Hearing Rescheduled 10-30-03

Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities P.O. Box 21040, St. John=s, NL. A1A 5B2 Tel: (709) 726-8600 - Fax: (709) 726-9604 PUBLIC SERVICE BULLETIN OCTOBER 30, 2003 Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro General Rate Hearing and Public Participation Days set for the Town of Labrador City and Happy Valley-Goose Bay Rescheduled The Board wishes to advise that the proceedings that were scheduled to commence in Labrador West on Monday, November 3 have been postponed and will be rescheduled to a later date. This postponement is as a result of a request from the Towns of Labrador City and Wabush, who are registered intervenors in Hydro’s General Rate Hearing. The public participation days previously scheduled for Wednesday, November 5 at the O’Brien Hall in Labrador City and Thursday, November 6 at the St. Anglican Parish Hall in Happy Valley-Goose Bay will also be rescheduled. The Board will advise the public of the revised start date and schedule. For further information please contact the Board Secretary as detailed below. _______________________________________________________________________________ Media Contact: Cheryl Blundon, Board Secretary Office: Suite E210, Prince Charles Building, 120 Torbay Road, St. John’s By mail: P.O. Box 21040, St. John’s, NL, A1A 5B2 Phone: (709) 726-8600 Toll Free: 1-866-782-0006 E-mail: [email protected] FAX TRANSMISSION DISTRIBUTION LIST TO: FAX NO. E-mail (as requested) CBC Radio- St. John’s 576-5234 [email protected] CBC Television 576-5144 [email protected] CBC-Radio- Labrador City 944-5472 CBC-Radio- Goose Bay 896-8900 NTV Television Network - Newsroom 722-3207 CHOZ Radio 726-3300 Steele Communications -CFCB Radio- Labrador City 282-5543 -CFCB Radio- Labrador- Goose Bay 896-8708 Doug Learning, VOCM 726-4633 [email protected] Pat Doyle, The Telegram 364-3939 [email protected] Robinson-Blackmore Publishing 722-2228 (Please make available to the Aurora and the Labradorian your papers) MUNICIPALITIES Town of Port Hope Simpson 960-0387 Town of Mary’s Harbour 921-6255 Town of West St.