The Fifteenth Mount Haemus Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AVAS Newsletter 2016

AVON VALLEY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER December 2016 Editorial This year is a swan song for me as this twelfth edition of the Newsletter will be my last one. I feel that I have had a good innings and that it is time to pass baton on to someone who will bring a fresh vision to the task. As I stated last year there is a distinct move away from excavation work in archaeology and this trend is continuing, but our work with resistivity techniques to do non-invasive searches, supplemented by the use of Magnetometry, using some equipment borrowed from Bournemouth University has proved a revelation. For those who wish to know more and see some of the results, then attendance at our Members Evening in January is a must! We really are discovering more and disturb less! My last edition of our newsletter, like a number of previous copies is taking in some practical archaeological topics and attempting to stimulate members to seek out even more interesting places based upon the travels of a number of our members. Our blog site continues to flourishing. So once again, our thanks go to Mike Gill for his continuing work in keeping the news of activities and plans of AVAS available to our members and the general public at large. So let us all support them with any useful news or other input that we, as members, might come up with. N.B. The address on the web for our blogsite is at the bottom of this page. I hope that this edition of the Newsletter will be both stimulating and entertaining and wish you all great year of archaeology in 2017. -

Archaeology Book Collection 2013

Archaeology Book Collection 2013 The archaeology book collection is held on the upper floor of the Student Research Room (2M.25) and is arranged in alphabetical order. The journals in this collection are at the end of the document identified with the ‘author’ as ‘ZJ’. Use computer keys CTRL + F to search for a title/author. Abulafia, D. (2003). The Mediterranean in history. London, Thames & Hudson. Adkins, L. and R. Adkins (1989). Archaeological illustration. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Adkins, L. and R. A. Adkins (1982). A thesaurus of British archaeology. Newton Abbot, David & Charles. Adkins, R., et al. (2008). The handbook of British archaeology. London, Constable. Alcock, L. (1963). Celtic Archaeology and Art, University of Wales Press. Alcock, L. (1971). Arthur's Britain : history and archaeology, AD 367-634. London, Allen Lane. Alcock, L. (1973). Arthur's Britain: History and Archaeology AD 367-634. Harmondsworth, Penguin. Aldred, C. (1972). Akhenaten: Pharaoh of Egypt. London, Abacus; Sphere Books. Alimen, H. and A. H. Brodrick (1957). The prehistory of Africa. London, Hutchinson. Allan, J. P. (1984). Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds from Exeter 1971-1980. Exeter, Exeter City Council and the University of Exeter. Allen, D. F. (1980). The Coins of the Ancient Celts. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. Allibone, T. E. and S. Royal (1970). The impact of the natural sciences on archaeology. A joint symposium of the Royal Society and the British Academy. Organized by a committee under the chairmanship of T. E. Allibone, F.R.S, London: published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. Alves, F. and E. -

2013 CAG Library Index

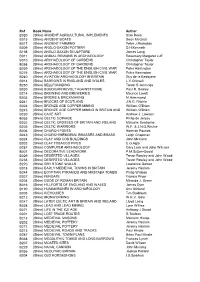

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

Parker Pearson, M 2013 Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International, No. 16 (2012-2013): 72-83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ai.1601 ARTICLE Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present Mike Parker Pearson* Over the years archaeologists connected with the Institute of Archaeology and UCL have made substantial contributions to the study of Stonehenge, the most enigmatic of all the prehistoric stone circles in Britain. Two of the early researchers were Petrie and Childe. More recently, colleagues in UCL’s Anthropology department – Barbara Bender and Chris Tilley – have also studied and written about the monument in its landscape. Mike Parker Pearson, who joined the Institute in 2012, has been leading a 10-year-long research programme on Stonehenge and, in this paper, he outlines the history and cur- rent state of research. Petrie and Childe on Stonehenge William Flinders Petrie (Fig. 1) worked on Stonehenge between 1874 and 1880, publishing the first accurate plan of the famous stones as a young man yet to start his career in Egypt. His numbering system of the monument’s many sarsens and blue- stones is still used to this day, and his slim book, Stonehenge: Plans, Descriptions, and Theories, sets out theories and observations that were innovative and insightful. Denied the opportunity of excavating Stonehenge, Petrie had relatively little to go on in terms of excavated evidence – the previous dig- gings had yielded few prehistoric finds other than antler picks – but he suggested that four theories could be considered indi- vidually or in combination for explaining Stonehenge’s purpose: sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental. -

Walking the Path of the Solitary Druid

Spring Equinox Issue Year of the Reform “LII” March 21, 2015 c.e. Volume 32, Issue 2 Editor’s Note: Blessings of the Spring on you. I hope you enjoyed the solar eclipse and have survived the late winter storms in the north-east. Deadline for Beltane submissions is April 22nd Send to [email protected] We invite you to join our Facebook groups such as: https://www.facebook.com/groups/2455316244/ RDNA https://www.facebook.com/groups/reforned.druids/ RDG Table of Contents News of the Groves Druid Poems Druid Blogs & Links Druid Videos Druid Pictures & Art Inoculative Libations to the Land Druid Debate 1: Non Celtic Druidism Druid Debate 2: Wilting Groves Book: The Awen Alone: Walking Solitary Druid NEWS OF THE GROVES Oakdale Grove: News from Minnesota I'm starting to create a few more stone sigil pendants in preparation for Beltane at Carleton. Not sure if anyone is planning on making the pilgrimage for vigiling, but it's good to prepare. I set up my most elaborate work altar ever on my desk now that my department has settled in at the headquarters building. The Schefflera tree pot is the mini sacred grove, yellow quartz "standing stone" at its center was a gift from my meditation seminars I'm enrolled in here at work, the plate makes a convenient coaster for my tea mug (effectively a chalice). The "altar" is the jar of water from Lake Superior which was collected after my grove consecrated the lake itself last October. I have a stone pendant with the Druid Sigil engraved. -

The Druids Voice 2.2PNG.Pub

© Steve Tatler The Sacredness and Mysticism of Green and Trees Marion Pearce CEREMONY, RITUAL, AND PRAYER Graeme k Talboys Silbury Hill Philip Shallcrass THETHE DRUIDDRUID NETWORKNETWORK The Druid Network and The Druids Voice Office 88 Grosvenor Road Dudley DY3 2PR United Kingdom © 2003 to the TDNTDN or the respective authors where indicated . We gratefully solicit and accept contrib u- tions for this magazine. Artwork and/or ph otography is best sent as a PC based file such as jpeg, gif, tiff, bmp or similar but originals on paper will be accepted but wil l necessitate scanning into the computer. Similarly all articles, texts, poetry, news and events is best received in txt, doc, r tf or pub files for copy and pasting into our doc uments. Type or print will be entered using OCR.. Handwritten work is difficult for us to manage but we are happy to see if we can use it. We cannot pay for any co n- tr ibutions. All postal enquiries must be a c- companied by an SSAE. (Ed) Cloaks,Cloaks, Tabards, Flags, and much more…. RobesRobes from £65 of the life , the achievements sis, and you are advised to To , The Druids Voice and the character of our d e- check regularly for changes. co ntinuing in its mission to parted brother Dylan Ap It is a dynamic and vibrant boldly go where no Druid Thuin. site, not only due to the co n- Ne twork journal has gone b e- tinual work of Bobcat and fore. Things have moved on with David, but also due to the n u- The Druid Network since the merous voluntary helpers We, here in Britain, find that last issue (2.1) of TDV. -

Religion and the Return of Magic: Wicca As Esoteric Spirituality

RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD March 2000 Joanne Elizabeth Pearson, B.A. (Hons.) ProQuest Number: 11003543 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003543 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION The thesis presented is entirely my own work, and has not been previously presented for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. The views expressed here are those of the author and not of Lancaster University. Joanne Elizabeth Pearson. RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY CONTENTS DIAGRAMS AND ILLUSTRATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi INTRODUCTION: RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC 1 CATEGORISING WICCA 1 The Sociology of the Occult 3 The New Age Movement 5 New Religious Movements and ‘Revived’ Religion 6 Nature Religion 8 MAGIC AND RELIGION 9 A Brief Outline of the Debate 9 Religion and the Decline o f Magic? 12 ESOTERICISM 16 Academic Understandings of -

Aontacht V6I4

Aontacht ISSN 2044-1339 Volume 6, Issue 4 Creating Unity Through Community Secrets Memories, Lives & Dreams Volume 6 Issue 4 Spring/Autumn 2014 Brought to you by the community of Druidic Dawn Aontacht • 1 (www.druidicdawn.org) Volume 6, Issue 4 aontacht creating unity in community 27 Eight Common Uses of Scotch Pine Essential 8 Dr Gwilym Morus Oil Feature Interview REVIEWS Z12 Modern Druid Nature Mysticism 35 Europe Before Rome: A Site-By-Site Tour Dr Karen Parham of the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages 23 Chance, Magick and the Will of Eris 36 The Story of Light Renard 36 Essays in Contemporary Paganism 25 Knowledge of the Oak Andrew "Bish" Peers DEPARTMENTS 29 Taliesin's Grave, the Black Road 3 Contributors Page and Gwion's Hill. Dr. G 6 From The Desk 32 Three Plants for Insomnia David C. Corrin 7 News from the Druidic Dawn Management Team 19 Community Shopping 15 If You Want To See Visions 37 Community Calendar Alison Leigh Lilly 39 What is in the next Issue? 21 TravelDream Lisa Du Fresne Cover photo: Clettwr RiverValley Photo Druidic Dawn 2014 Aontacht • 2 Volume 6, Issue 4 aontacht Contributors creating unity in community Secrets Memories, Lives & Dreams r Gwilym Morus: Editor D based in Mid wales at Mach- Vacant ynlleth. Gwilym specialises in Medieval Welsh Co-Editor poetry and the Welsh Bardic tradition, Together Lucie Marie-Mai DuFresne with presenting an online course delving into the Production Manager Symbolic Keys of Welsh Mythology. Dr Gwilym Druidic Dawn Rep. Nigel Dailey Morus is also an accompanied musician in the modern sense, but also has explored the court Feature Editor - Wild Earth bardic poet medieval performance and delivery. -

Paganism.Pdf

Pagan Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Author .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Beliefs, Teachings, Wisdom and Authority ....................................................................................................................... 2 Basic Beliefs ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Sources of Authority and (lack of) scriptures ........................................................................................................................ 4 Founders and Exemplars ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ways of Living ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Guidance for life .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ritual practice ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Freidin-1 NICHOLAS PHILIPPE JEAN FREIDIN

Freidin-1 NICHOLAS PHILIPPE JEAN FREIDIN Curriculum vitae Date of birth: 8 September, 1951 Place of birth: Paris, France Marital status: Divorced, one daughter Citizenship: France, United States of America Addresses: OFFICE: HOME: Department of Sociology 1903 Wiltshire Boulevard and Anthropology Huntington Marshall University West Virginia 25701-4136 Huntington West Virginia 25755-2678 (304) 696 2794 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: DPhil. (Ph. D) Keble College, University of Oxford 1981 Thesis title: The Paris Basin in the Context of the Early Iron Age Supervisor: Professor Sir Barry W. Cunliffe Examiners: Professor Stuart Piggott Dr. Daphne Nash Diploma in Eur. Keble College, University of Oxford 1975 Archaeology A.B. (History) Georgetown University, Washington D.C. 1973 Zeugnis Deutschen Sprachkurse fur Auslander, 1973 Wiener Internationale Hochschulkurse, Universitat Wien, Vienna University of New Hampshire, 1969-71 Durham, N.H. Freidin-2 PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES: 1998-present Professor of Anthropology (tenured), Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Marshall University, Huntington, W. Va. 1987 - 1998 Associate Professor of Anthropology (tenured), Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Marshall University, Huntington, W. Va. 1991 Co-Project Director, Excavations at the Saint-Albans Site (46-Ka-27), sponsored by the Friends of St-Albans Archaeology, Inc., and the City of St- Albans, Kanawha County, W. Va. (in cooperation with Dr. Janet Brashler, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, Michigan) 1990 Project Director, Excavations at the Madie Carroll House, sponsored by the Madie Carrroll House Preservation Society, Inc., Guyandotte, Cabell County, W. Va. 1988 - 1989 Project Director, The Snidow (46-Mc-01) Project, sponsored by the West Virginia Archaeological Society, the Council for West Virginia Archaeology, Concord College and Marshall University 1983 – 1987 Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Marshall University, Huntington, W. -

The Avebury to Norwich 'Thunder Run'

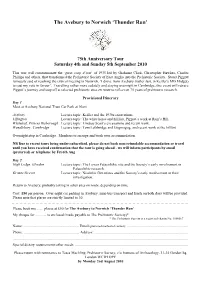

The Avebury to Norwich ‘Thunder Run’ 75th Anniversary Tour Saturday 4th and Sunday 5th September 2010 This tour will commemorate the ‘great coup d’etat’ of 1935 led by Grahame Clark, Christopher Hawkes, Charles Phillips and others, that transformed the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia into the Prehistoric Society. Stuart Piggott famously said of reaching the critical meeting in Norwich, ‘I drove from Avebury (rather fast, in Keiller's MG Midget) to cast my vote in favour’. Travelling rather more sedately and staying overnight in Cambridge, this event will retrace Piggott’s journey and stop off at selected prehistoric sites en route to reflect on 75 years of prehistoric research. Provisional Itinerary Day 1 Meet at Avebury National Trust Car Park at 10am Avebury Lecture topic: Keiller and the 1930s excavations. Uffington Lecture topic: The white horse and hillfort, Piggott’s work at Ram’s Hill. Whiteleaf, Princes Risborough Lecture topic: Lindsay Scott’s excavations and recent work. Wandlebury, Cambridge Lecture topic: Tom Lethbridge and Gogmagog, and recent work at the hillfort. Overnight stop in Cambridge. Members to arrange and book own accommodation. NB Due to recent tours being under-subscribed, please do not book non-refundable accommodation or travel until you have received confirmation that the tour is going ahead - we will inform participants by email (preferred) or telephone by Fri 6th Aug Day 2 High Lodge, Elvedon Lecture topic: The Lower Palaeolithic site and the Society’s early involvement in Palaeolithic research. Grimes Graves Lecture topic: Neolithic flint mines and the Society’s early involvement in their investigation. -

Living Druidry: Magical Spirituality for the Wild Soul Free

FREE LIVING DRUIDRY: MAGICAL SPIRITUALITY FOR THE WILD SOUL PDF Emma Restall Orr | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2005 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780749924973 | English | London, United Kingdom Druid Magic Handbook: Ritual Magic Rooted In The Living Earth - Heaven & Nature Store Post a Comment. Pages Home What is Druidry? A druid study program. Various druid groups offer druid study programs. I started with AODA, but then went my own way. Below is my own druid study program. It is similar to the AODA program, but it removes magic and divination, and adds additional optional areas of study such as mythology, languages, yoga, and gardening. First Degree Spend at least a year on the following activities: Druidry 1 Read books by at least two different authors about modern druidry. Bonewits, Isaac. Bonewits' Essential Guide to Druidism. Living Druidry: Magical Spirituality for the Wild Soul, Philip. Druid Mysteries. The Rebirth of Druidry. What Do Druids Believe? Ellison, Robert. The Solitary Druid. Greenfield, Trevor. Paganism Greer, John Michael. The Druidry Handbook. Orr, Emma Restall. Taelboys, Graeme K. Treadwell, Cat. A Druid's Tale. White, Julie, and Talboys, Graeme K. Alhouse-Green, Miranda. Caesar's Druids: An Ancient Priesthood. Cunliffe, Barry. The Ancient Celts. Ellis, Peter Berresford. A Brief History of the Druids. Hutton, Ronald. The Druids. Blood and Mistletoe. James, Living Druidry: Magical Spirituality for the Wild Soul. The World of the Celts. King, John Robert. Markale, Jean. The Druids: Celtic Priests of Nature. Meditation 4 Practice meditation every day, at least 10 minutes a day. Brown, Nimue. Druidry and Meditation. Nichol, James. Contemplative Druidry.