Folk-Lore Journal:— As Long As a Corpse Is Still in a House, the Looking-Glass Is Turned Round, Or Covered, and the Clock Remains Stopped

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investment in Crofting?

THE CROFTER rooted in our community The journal of the Scottish Crofting Foundation, the only member-led organisation dedicated to the promotion of crofting and the largest association of small-scale food producers in the UK SEPTEMBER 2009 Number 84 Investment Commitment of Scottish Government in crofting? called into question by Reform Bill The evidence is clear HE quESTION needs to be asked. Why, for the second time around, has this bill been received with so much hostility by crofters? On the surface, the process taken to arrive at this point seems to have been O CULTIVATE the health of crofting T developmentally correct – there was a full inquiry into crofting, into which crofters had ample and to achieve economic and opportunity to contribute; a comprehensive analysis and set of recommendations was produced; social resilience of communities in T the Scottish Government responded to this and drafted a bill. However, if one looks a little rural Highlands and Islands, the Scottish closer it can be seen that flaws in the process – misunderstandings, misinterpretations, lack of Government must invest in crofting. participation – have led to an almost total rejection of the draft bill by the very people who gave The Government claims to be investing evidence to the inquiry, the crofters. The key to good development practice is participation and in crofting but this claim is not adequately this is what has been lacking at various stages of this process. reflected in practice. The following are For example, the Committee of Inquiry on Crofting -

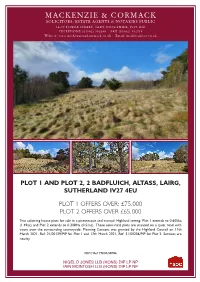

Mackenzie & Cormack

MACKENZIE & CORMACK SOLICITORS, ESTATE AGENTS & NOTARIES PUBLIC 16-18 TOWER STREET, TAIN, ROSS-SHIRE, IV19 1DZ TELEPHONE (01862) 892046 FAX (01862) 892715 Website: www.mackenzieandcormack.co.uk Email: [email protected] PLOT 1 AND PLOT 2, 2 BADFLUICH, ALTASS, LAIRG, SUTHERLAND IV27 4EU PLOT 1 OFFERS OVER: £75,000 PLOT 2 OFFERS OVER £65,000 Two adjoining house plots for sale in a picturesque and tranquil Highland setting. Plot 1 extends to 0.605ha (1.49ac) and Plot 2 extends to 0.208Ha (0.51ac). These semi-rural plots are situated on a quiet road with views over the surrounding countryside. Planning Consent was granted by the Highland Council on 11th March 2021, Ref: 21/00129/PIP for Plot 1 and 17th March 2021, Ref: 21/00206/PIP for Plot 2. Services are nearby. HSPC Ref: MK04/58786 NIGEL D JONES LLB (HONS) DIP LP NP IAIN MCINTOSH LLB (HONS) DIP LP NP RED LINE denotes Application area. BLUE LINE denotes land owner by Applicant. STATUS: PLANNING APPLICATION SITE AREA 6050m². Set in a spectacular rural location, Altass is an ideal area for to ROSEHALL enjoying wildlife and scenic walks. This is an excellent base for stalking and fishing with a 9-hole golf course available approximately 12 miles away at Bonar Bridge. Local amenities are available nearby include Rosehall Primary PROPOSED HOUSE SITE, Plot 1, 230m south/west of 2 Badfluich, School, Invercassley Stores & Tearoom, Ravens Rock Altass, LAIRG, IV27 4EU. Forest Walk and Achness Hotel. Further facilities can be found at Bonar Bridge to the East and Lairg to the North. -

Altnaharra Site Leaflet

Altnaharra Club Site Explore the Scottish Highlands Places to see and things to do in the local area Make the most of your time 01 10 Melvich Talmine 03 Halkirk Shegra Eriboll Skelpick 04 Wick Forsinain 09 Syre Achavanich Allnabad Achfary 05 08 Badanloch Drumbeg 07 Lodge Braemore Stoer Crask Inn Stonechrubie Dalnessie Portgower 02 Drumrunie Lairg 11 06 Golspie Visit Don’t forget to check your Great Saving Guide for all the 1 Cape Wrath latest offers on attractions throughout the UK. Great Savings See some of Britain’s highest Guide camc.com/greatsavingsguide cliffs, seals and wildlife and the spectacular Cape Wrath Lighthouse at Scotland’s most north-westerly 5 Fishing point. Members staying on site may fly 2 Ferrycroft Countryside fish from the shore, and also row, Centre sail or paddle your own boat on Loch Naver. Beside the renowned archaeological site Ord Hill and 6 Clay pigeon shooting surrounded by forest, a great base Visit one of Big Shoots 150 for discovering wildlife and history. locations at Altass to experience the thrills of cracking clays. 3 Strathnaver Museum Discover the area’s vibrant culture and mythical past, inherited from Norse and Gaelic ancestors. 4 Bird Watching From mountain top to sea shore, this is a first class area for birdwatching. RSPB Forsinard Reserve is nearby and thrives with bird life in summer. Cape Wrath Cycle 8 National Cycle Network The nearest route to the site is 1, Dover to Shetland. 9 Mountain Biking The Highlands has been recognised by the International Mountain Bike Association as one of the great biking destinations and offers an abundance of trails, forest and wilderness riding to suit all levels and abilities. -

Ardgay District

ARDGAY & DISTRICT Community Council newsletter Price: £1.00 ISSN 2514-8400 = Issue No. 43 = SPRING 2019 = Ardgay and District Community Plan is now available to the public KYLE OF SUTHERLAND Development Trust and Sutherland Community Partnership have published the find- ings of a consultation that invited res- idents to provide their view on what they thought could best improve the community. (Page 6) “Cherished” and virtually unaltered in the last 200 years Croick church is “arguably the most authentic sur- vivor” of all 32 Thomas Telford Parliamentary Kirks. IN THE LAST ISSUE we published a Rev Mary Stobo has written an ex- letter to the Editor highlighting tensive article which brings invalu- Mac & Wild Falls of how the trees around Croick chuch able insight into the history of the Shin will re-open 23rd were overwhelming the building, building, on what has been done in March with exciting food and the potential damage faced by the past and what is being done now the church (fallen branches, roots, to preserve it in the best possible and events Page 12 clogged gutters, etc). In this issue, way for future generations. (Page 4) Time to join your local Stories of the people of Glencalvie community gym! Page 21 An account of some not so well-known facts Page 16 2019 is the International The abolition of the runrig tenure system Page 18 Year of the Salmon Page 14 The Curlew 20 red squirrels, new a needs all the help residents of Ledmore 36 pages featuring Lettes to the Editor, it can get & Migdale Opening times, Telephone guide, Bus & Train timetable, Page 31 Page 20 Sudokus & Crossword Sample Menu Every Monday 11.30am-2pm Bonar Bridge Community Hall Everyone Welcome Roasted Red Pepper and Tomato Soup —00— Chicken Mornay and Rice —00— Apple Pie with Ice Cream —00— Toasties - Cheese/Tuna mayo/Ham —00— Childrens’ Snack Boxes (sandwich, yoghurt, raisins and fresh fruit juice) —OO— Cappuccino, Mocha, Latte or Hot Chocolate Tea/Coffee Fruit Juice, Bottled Water—Still or Sparkling —OO— Takeaways must be ordered before 11.30am and collected by 1pm. -

PLACE-NAMES of SCOTLAND Printed by Neill Tfc Company FOK DAVID DOUGLAS

GIFT OF SEELEY W. MUDD and GEORGE I. COCHRAN MEYER ELSASSER DR. JOHN R. HAYNES WILLIAM L. HONNOLD JAMES R. MARTIN MRS. JOSEPH F. SARTORI to the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SOUTHERN BRANCH JOHN FISKE JOSEPH H'DONOI f RARE BOOKS PLACE-NAMES OF SCOTLAND Printed by Neill tfc Company FOK DAVID DOUGLAS. LONDON . SIMPKIN, MARSHALL. HAMILTON, KENT, AND CO., LIM. CAMBRIDGE . MACMILLAN AND BOWES. GLASGOW . JAMES MACLKHOSE AND SONS. PLACE-NAMES OF SCOTLAND JAMES B. JOHNSTON, B.D. MIKISTK.r: (IF THE VKV.V. CIU'IKTI, 1'ALKIIIK EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS 1892 ( ;DA < 69 PKEFACE. THAT this book is an attempt, only an attempt, with many deficiencies, the writer of it is well aware. The would-be severest critic could not criticise it more severely than he. But a pioneer may surely at all "times claim a certain measure of grace and indulgence, if the critic find here anything that is truly useful all, he is courteously entreated to lend his much- needed aid to make the book better, instead of picking out the many shortcomings which a first attempt in this philological field cannot but display. The book has been long a-gathering, and has been compiled in the mere shreds and fragments of time which could be spared from the conscientious discharge of exception- ally heavy ministerial work. It has been composed away from all large libraries, to which the writer was able to make occasional reference and both in only ; the writing and in the passing through the press though he has done his best he has been subject to incessant interruption. -

KYLEVIEW ALTASS, ROSEHALL, LAIRG, IV27 4EU 9Th July 2020 ZL304314 Terms and Conditions

Home Report KYLEVIEW ALTASS ROSEHALL LAIRG IV27 4EU Energy Performance Certificate YouEnergy can use this Performance document to: Certificate (EPC) Scotland Dwellings KYLEVIEW, ALTASS, ROSEHALL, LAIRG, IV27 4EU Dwelling type: Detached bungalow Reference number: 2010-4723-0200-0881-1206 Date of assessment: 09 July 2020 Type of assessment: RdSAP, existing dwelling Date of certificate: 09 July 2020 Approved Organisation: ECMK Total floor area: 150 m2 Main heating and fuel: Electric storage heaters Primary Energy Indicator: 677 kWh/m2/year You can use this document to: • Compare current ratings of properties to see which are more energy efficient and environmentally friendly • Find out how to save energy and money and also reduce CO2 emissions by improving your home Estimated energy costs for your home for 3 years* £9,708 See your recommendations report for more Over 3 years you could save* £3,666 information * based upon the cost of energy for heating, hot water, lighting and ventilation, calculated using standard assumptions Very energy efficient - lower running costs Current Potential Energy Efficiency Rating (92 plus) A This graph shows the current efficiency of your home, (81-91) B 90 taking into account both energy efficiency and fuel costs. The higher this rating, the lower your fuel bills (69-80) C are likely to be. (55-68) D Your current rating is band E (48). The average rating for EPCs in Scotland is band D (61). (39-54 E 48 (21-38) The potential rating shows the effect of undertaking all F of the improvement measures listed within your (1-20) G recommendations report. -

Sutherland Local Plan: Natural and Cultural Heritage Feedback Comments

SUTHERLAND LOCAL PLAN: NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE FEEDBACK COMMENTS NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE For example: Are there any development opportunities associated with the environment that you’d like to see encouraged? Are there any areas you’d like to see protected or those which would benefit from some improvement? General Comments • Sutherland has the most dramatic scenery in the UK and Tongue and Farr has the greatest spaces of part of flow-country, & “The Queen of Mountains”. Ben Loyal, and with the sea being to the north of us the blue of the sea and the coast on a sunny day is more dramatic than other places (so there is scope for expansion of tourism) It gives uplift to many people from all over UK. Without involving false development so the whole needs protection. • I moved to the Sutherland area from the Netherlands this year, because I really appreciate the wide open spaces and wildlife. Promote the area to tourists and please realise how valuable nature is (but I’m sure you do). • Any development should be sympathetic to the Local Environment. • In Norway all country primaries had a wood and each child planted a tree before leaving. Primary 7 children should have country skills taught at least one day per week. Give them a pride in their home background – not a useless country bumpkin. Bird watching/butterflies/wild flowers. How to hedge ditch, fence, build walls etc. • It is quite possible to develop an area without destroying much of the natural beauty. There will still be loads of underused ‘natural beauty’ event if lots of the land is developed! Get something moving for the next generation before it is too late. -

Creich Community Council

Minutes approved 19/01/2021 CREICH COMMUNITY COUNCIL Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday 17th November 2020 at 7.30pm on Zoom Present: Pete Campbell, Chair (PC), Marcus Munro, Vice Chair (MM), Mary Goulder, Treasurer/Secretary (MG), Russell Smith (RS), Norman MacDonald (NM) Apologies: John White (JW), Rikki Vetters (RV), Brian Coghill (BC) Also present: Hamish Munro (HM), Jessie Munro (JM), Michael Baird (MB) Police representative: None present Item 1. Welcome/apologies (as above). Police report. This meeting immediately followed the closure of the AGM. Personnel remained unchanged. No report received from the police despite confirmation of the date. MB reported that there have been numerous speeding incidents noted on the Bonar-Ardgay straight. He has been in communication with Rhoda Grant MSP who in turn has contacted Donna Manson, THC and Superintendent Trickett. THC are said to be reviewing the speed restrictions and further actions by the police are anticipated. Once again, the idea was put forward for a continuous 30mph limit from the outskirts of Ardgay through Bonar to the outskirts on both the Dornoch and Lairg roads. MM said that while the reduction of speed on the complete straight would be welcomed the main issue is the stretch approaching Bonar Bridge from Ardgay past Ardgay Game and The Hub. He suggested reinstating ‘Smiley Sid’, the CC’s own speed advice sign, on a lamppost at the entry into Bonar from Ardgay. This requires THC to connect the equipment to the appropriate streetlight. Such a request will be made. KC/MG Action. The CC will continue to support A&DCC in its efforts to resolve this issue. -

Two Plots, South of the Old Church Altass, Rosehall Bellingram.Co.Uk

Two Plots, South Of The Old Church Altass, Rosehall bellingram.co.uk Two attractive neighbouring building plots in Rosehall is within walking distance where these is a primary Important Notice: the village of Altass both with Planning school, village hall and a hotel. The nearest towns are Bonar These sale particulars were prepared on the basis of Bridge and Lairg where there are shops, banks, surgeries, information provided to us by our clients and/or our local Permission in Principle for a one and a half schools and a railway station at Lairg. Inverness is about an knowledge. Whilst we make every reasonable effort to ensure storey dwelling house hour away by road and has all the facilities commensurate that they are correct, no warranty or guarantee is given and with a major regional centre. These include a good shopping prospective purchasers should not rely upon them as Dornoch 22 miles, centre, theatre, hospital, schools and a mainline railway statements or representations of fact. Furthermore neither Bonar Bridge 09 miles station. Inverness airport has a variety of services both Bell Ingram LLP or its Partners or employees assume any Inverness 46 miles domestic and international. responsibility therefore. In particular: i) prospective purchasers should satisfy themselves as to the Services structural condition of any buildings or other erections and the state of repair of any services, appliances, equipment or Rural location yet within easy driving distance of all Mains water and electricity are understood to be available facilities; ii) any photographs included in these particulars are amenities. nearby. Drainage will be to a water treatment tank. -

Mr Alexander Campion

Agenda 7.2 item Report PLN/058/18 no THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: North Planning Applications Committee Date: 11 September 2018 Report Title: 18/02744/FUL - Land 90M SW Of Kinvara, Altass Report By: Area Planning Manager – North 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 Applicant: Mr Alexandar Campion Description of development: Erection of 2 no. houses Ward: 1 - North, West and Central Sutherland Category: Local Reasons Referred to Committee: 5 objections All relevant matters have been taken into account when appraising this application. It is considered that the proposal accords with the principles and policies contained within the Development Plan and is acceptable in terms of all other applicable material considerations. 2. Recommendation 2.2 Members are asked to agree the recommendation to approve as set out in section 11 of the report. 3. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 3.1 The application seeks consent for the erection of two houses, to be used primarily for holiday letting purposes. The proposed development also includes formation of a new access and installation of private drainage arrangements. The proposed houses have been designed specifically to provide functional accommodation for disabled people. 3.2 No pre-application advice was sought in advance of the submission of the planning application. 3.3 There is no infrastructure on site at present. 3.4 The application is supported by a Supporting Statement and a further document has been lodged by the applicant to provide clarity in response to objections. 3.5 Variations: No variations have been made to the proposal since it was lodged. As noted above however, further information has been submitted in the form of a response to objections. -

Residential Property Kyle Lodge, Altass, Lairg

Residential Property Kyle Lodge, Altass, Lairg The Property This four bedroom detached property is set in approximately 1.5 acres of well maintained & established grounds. Situated in a prominent and elevated position this home enjoys stunning open countryside views which overlook river Oykel and Struie. The spacious accommodation comprises of lounge, kitchen/dining room, conservatory, utility room, shower room, family bathroom and four bedrooms with bedroom 1 and 2 sharing a Jack and Jill shower room. There is a large gravel driveway with ample parking for several vehicles which leads to a double garage with power & light. The property benefits from double glazing and oil central heating throughout. This property needs to be seen to be appreciated and would make an ideal family home. The Area The property is situated in a small rural community of Altass with spectacular views over the river Oykel valley framed with trees with additional views of Struie, there is a primary school in Altass which is conveniently located just over a mile from the property. Kyle Lodge is situated approximately 8 miles from the village of Bonar Bridge, where the Kyle of Sutherland meets the Dornoch Firth. This attractive area is an ideal location for exploring the North Highlands and a number of leisure pursuits nearby plus hill and woodland walks. And convenient to the fishing beats and for those who enjoy any outdoor pursuits. In Bonar Bridge there are local shops, GP surgery, golf club, restaurant and pubs. Invershin train station provides a regular commuter service to the Highland capital, Inverness, there are also three other railway stations within a 10 mile radius. -

Ardgay District

ARDGay & DISTRICT Community Council newsletter Price: £1.00 ISSN 2514-8400 = Issue No. 40 = SUMMER 2018 = TO INCREASE COMMUNITY RESILIENCE Ardgay & District CC: Two Public Access Defibrillators for Ardgay and Culrain THE TWO NEW PADs are designed to be used by an- yone in the event of a sud- den cardiac arrest. CPR training will be offered by the Scottish Ambulance and the Scottish Fire & Rescue Services on Sun- day 24th June, from 10 am to 3 pm, at Ardgay Pub- lic Hall. Photographed: Silvia Muras, Vice Chair of Ardgay & District CC and leader of the project, Andy Waugh (right) and Calum MacKinnon. © LATEEF OKUNNU alongside the recently in- stalled defibrillator at Ar- Mac & Wild comes dgay Hall. Pages 4 & 5 to Falls of Shin New Central Sutherland Outreach London’s favourite Scottish restaurant Programme from Citizens Advice Mac & Wild announce the launch of their Bureau local branch (Page 14) third restaurant, opening late June 2018. TAKING MAC & WILD BACK to its Highland roots, Ardgay Post Office is back with founders Andy Waugh and Calum Mackinnon are delighted to announce they have taken over the site new opening times Page 10 New at the Falls of Shin visitor centre. Pages 8 & 9 Postmaster in Bonar Bridge Page 12 Your essential guide 100 years ago Ardgay a to local events for all was ‘invaded’ by North 36 pages featuring Opening times, tastes and American lumberjacks Telephone guide, ages Bus & Train timetable, Sudoku & Crosswords Page 25 Page 18 Volunteering Opportunities At East & Central Sutherland Citizens Advice Bureau We are