"Childhood and the Challenge of Fat Masculinity." Hitchcock's Appetites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2009 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2009 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY VICKY CRISTINA IN BRUGES BOTTLE SHOCK ARSENIC AND IN BRUGES BARCELONA (2008-UK/Belgium) (2008) OLD LACE (2008-UK/Belgium) (2008-Spain/US) in widescreen in widescreen in widescreen in Catalan/English/Spanish w/ (1944) with Chris Pine, Alan with Cary Grant, Josephine English subtitles in widescreen with Colin Farrell, Brendan with Colin Farrell, Brendan Hull, Jean Adair, Raymond with Rebecca Hall, Scarlett Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes, Rickman, Bill Pullman, Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes, Johansson, Javier Bardem, Clémence Poésy, Eric Godon, Rachael Taylor, Freddy Massey, Peter Lorre, Priscilla Clémence Poésy, Eric Godon, Penelopé Cruz, Chris Ciarán Hinds. Rodriguez, Dennis Farina. Lane, John Alexander, Jack Ciarán Hinds. Messina, Patricia Clarkson. Carson, John Ridgely. Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Directed and Co-written by Written and Directed by Woody Allen. Martin McDonagh. Randall Miller. Directed by Martin McDonagh. Frank Capra. 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 & 8:30pm 5 & 8:30pm 6 & 8:30pm 7 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 8 & 8:30pm 9 Lincoln's 200th Birthday THE VISITOR Valentine's Day THE VISITOR Presidents' Day 2 for 1 YOUNG MR. LINCOLN (2007) OUT OF AFRICA (2007) THE TALL TARGET (1951) (1939) in widescreen (1985) in widescreen with Dick Powell, Paula Raymond, Adolphe Menjou. with Henry Fonda, Alice with Richard Jenkins, Haaz in widescreen with Richard Jenkins, Haaz Directed by Anthony Mann. -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 65–99. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 16:41 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption People say, “ Why don ’ t you make more costume pictures? ” Nobody in a costume picture ever goes to the toilet. That means, it ’ s not possible to get any detail into it. People say, “ Why don ’ t you make a western? ” My answer is, I don ’ t know how much a loaf of bread costs in a western. I ’ ve never seen anybody buy chaps or being measured or buying a 10 gallon hat. This is sometimes where the drama comes from for me. 1 y 1942, Hitchcock had acquired his legendary moniker the “ Master of BSuspense. ” The nickname proved more accurate and durable than the title David O. Selznick had tried to confer on him— “ the Master of Melodrama ” — a year earlier, after Rebecca ’ s release. In a fi fty-four-feature career, he deviated only occasionally from his tried and true suspense fi lm, with the exceptions of his early British assignments, the horror fi lms Psycho and The Birds , the splendid, darkly comic The Trouble with Harry , and the romantic comedy Mr. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

European Journal of American Studies, 5-4 | 2010 “Don’T Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early A

European journal of American studies 5-4 | 2010 Special Issue: Film “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema Ian Scott Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/8751 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.8751 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Ian Scott, ““Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema”, European journal of American studies [Online], 5-4 | 2010, document 5, Online since 15 November 2010, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/8751 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.8751 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early A... 1 “Don’t Be Frightened Dear … This Is Hollywood”: British Filmmakers in Early American Cinema Ian Scott 1 “Don't be frightened, dear – this – this – is Hollywood.” 2 Noël Coward recited these words of encouragement told to him by the actress Laura Hope-Crews on a Christmas visit to Hollywood in 1929. In typically acerbic fashion, he retrospectively judged his experiences in Los Angeles to be “unreal and inconclusive, almost as though they hadn't happened at all.” Coward described his festive jaunt through Hollywood’s social merry-go-round as like careering “through the side-shows of some gigantic pleasure park at breakneck speed” accompanied by “blue-ridged cardboard mountains, painted skies [and] elaborate grottoes peopled with several familiar figures.”1 3 Coward’s first visit persuaded him that California was not the place to settle and he for one only ever made fleeting visits to the movie colony, but the description he offered, and the delicious dismissal of Hollywood’s “fabricated” community, became common currency if one examines other British accounts of life on the west coast at this time. -

Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Axel KRUSI;

SYDNEY STUDIES Tragicomedy and Tragic Burlesque: Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead AxEL KRUSI; When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead appeared at the .Old Vic theatre' in 1967, there was some suspicion that lack of literary value was one reason for the play's success. These doubts are repeated in the revised 1969 edition of John Russell Taylor's standard survey of recent British drama. The view in The Angry Theatre is that Stoppard lacks individuality, and that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is a pale imitation of the theatre of the absurd, wrillen in "brisk, informal prose", and with a vision of character and life which seems "a very small mouse to emerge from such an imposing mountain".l In contrast, Jumpers was received with considerable critical approval. Jumpers and Osborne's A Sense of Detachment and Storey's Life Class might seem to be evidence that in the past few years the new British drama has reached maturity as a tradition of dramatic forms aitd dramatic conventions which exist as a pattern of meaningful relationships between plays and audiences in particular theatres.2 Jumpers includes a group of philosophical acrobats, and in style and meaning seems to be an improved version of Stoppard's trans· lation of Beckett's theatre of the absurd into the terms of the conversation about the death of tragedy between the Player and Rosencrantz: Player Why, we grow rusty and you catch us at the very point of decadence-by this time tomorrow we might have forgotten every thing we ever knew. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced info the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on untii complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

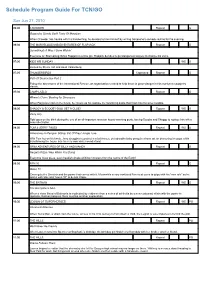

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Jun 27, 2010 06:00 CHOWDER Repeat G Gazpacho Stands Up/A Taste Of Marzipan When Chowder has trouble with his handwriting, he decides to train himself by writing Gazpacho's comedy routine for the evening. 06:30 THE MARVELOUS MISADVENTURES OF FLAPJACK Repeat G Something's A Miss / Gone Wishin' Everyone on Stormalong thinks Flapjack is a little girl. Flapjack decides to get dangerous surgery to change his voice. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Shura Taft and Heidi Valkenburg. 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Path Of Destruction Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Where's Clam / Bowling for Dinosaurs When Raj loses Clam in the forest, he covers up his mistake by convincing Lazlo that Clam has become invisible. 08:00 SHAGGY & SCOOBY-DOO GET A CLUE! Repeat WS G Party Arty Robi goes on the blink during the eve of an all-important mansion house-warming party, forcing Scooby and Shaggy to replace him wih a new robot butler. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES Repeat WS G Adventures In Penguin Sitting/ Cat Of Prey/ Jungle Love With Tom hot on his heels, Jerry struggles to protect a mischievous, yet adorable baby penguin whose set on devouring ice pops while transforming the house into his very own winter wonderland. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G Nergal's Pizza / Hey Water You Doing Everyone loves pizza, even freakish shape shifting monsters from the centre of the Earth! 09:30 BEN 10 Repeat G Gwen 10 Gwen gets the Omnitrix and the power that comes with it. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

Simply-Hitchcock-1587911892. Print

Simply Hitchcock Simply Hitchcock DAVID STERRITT SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2017 by David Sterritt Cover Illustration by Vladymyr Lukash Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-17-9 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Dedicated to Mikita, Jeremy and Tanya, Craig and Kim, and Oliver, of course Contents Praise for Simply Hitchcock ix Other Great Lives xiii Series Editor's Foreword xiv Preface xv Acknowledgements xix 1. Hitch 1 2. Silents Are Golden 21 3. Talkies, Theatricality, and the Low Ebb 37 4. The Classic Thriller Sextet 49 5. Hollywood 61 6. The Fabulous 1950s 96 7. From Psycho to Family Plot 123 8. Epilogue 145 End Notes 147 Suggested Reading 164 About the Author 167 A Word from the Publisher 168 Praise for Simply Hitchcock “With his customary style and brilliance, David Sterritt neatly unpacks Hitchcock’s long career with a sympathetic but sharply observant eye. As one of the cinema’s most perceptive critics, Sterritt is uniquely qualified to write this concise and compact volume, which is the best quick overview of Hitchcock’s work to date—written with both the cineaste and the general reader in mind. -

Invasion of the Body Snatchers Kathleen Loock

6 The Return of the Pod People: Remaking Cultural Anxieties in Invasion of the Body Snatchers Kathleen Loock Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), based on a novel by Jack Finney, has become one of the most influential alien invasion films of all time. The film’s theme of alien paranoia—the fear that some invis- ible invaders could replace individual human beings and turn them into a collective of emotionless pod people—resonated with widespread anxieties in 1950s American culture. It has been read as an allegory of the communist threat during the Cold War but also as a commen- tary on McCarthyism, the alienating effects of capitalism, conformism, postwar radiation anxiety, the return of “brainwashed” soldiers from the Korean War, and masculine fears of “the potential social, politi- cal, and personal disenfranchisement of postwar America’s hegemonic white patriarchy” (Mann 49). 1 Engaging with the profound concerns of its time, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is widely regarded as a signature film of the 1950s. Yet despite its cultural and historical specificity, the narrative of alien-induced dehumanization has lent itself to reinterpretations and re-imaginations like few others, always shifting with the zeitgeist and replacing former cultural anxieties with more contemporary and urgent ones. Siegel’s film has inspired three cinematic remakes over the last 55 years: Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Abel Ferrara’s Body Snatchers (1993), and, most recently, Oliver Hirschbiegel’s The Invasion (2007). Bits and pieces of the film have also found their way into the American popular imagination, taking the form of intermedial refer- ences to Invasion of the Body Snatchers in movies, television series, car- toons, and video games. -

The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films John T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films John T. Dunn Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, John T., "The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 758. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/758 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE REPRESENTATION OF DISABILITY IN THE MUSIC OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK FILMS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John Timothy Dunn B.M., The Louisiana Scholars’ College at Northwestern State University, 1999 M.M., The University of North Texas, 2002 May 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family, especially my wife, Sara, and my parents, Tim and Elaine, for giving me the emotional, physical, and mental fortitude to become a student again after a pause of ten years. I also must acknowledge the family, friends, and colleagues who endured my crazy schedule, hours on the road, and elevated stress levels during the completion of this degree.