Digital Music in Turbulence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

Night Ripper Game Free Download Night Ripper Game Free Download

night ripper game free download Night ripper game free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66afcb849cee8498 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Night Watch Puppet Combo Download Free. Posted: (8 days ago) May 01, 2020 · Download Minecraft Map. Download : Night Watch How to install Minecraft Maps on Java Edition. Inspired by a Puppet Combo game : NIGHT WATCH Texture Pack and map made by : Trevencraftxxx ( me :D ) Progress: 100% complete: Tags: Horror. Night. Creepy. Puzzle. Challenge Adventure. Nightwatch. 2. Night Watch | Puppet Combo Wiki | Fandom. Posted: (5 days ago) Night Watch is a 2019 horror game developed by Puppet Combo. The game is available for download on Puppet Combo's Patreon1. 1 Summary 1.1 Outcome 1 1.2 Outcome 2 1.3 Outcome 3 2 Trivia 3 Gallery 4 References The game follows a park ranger named Jim who was assigned on watch duty on top of the tower in the middle of the park, where he specifically has to check for fires and guide any … Night Watch is Out! Park Ranger HORROR - Puppet Combo. -

BMES V1 No2 Version2

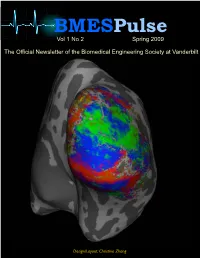

BMESPulse Vol 1 No 2 Spring 2009 The Official Newsletter of the Biomedical Engineering Society at Vanderbilt Design/Layout: Christine Zhang INSIDE THIS ISSUE Letter from the President 3 Editor: Christine Zhang Meet the BMES Officers 4 Contributing Writers: Pathfinder Therapeutics 6 A traipse into Law 8 Catherine Ruelens Paul Guillod Girl Talk 10 Yina Dong (UCSD) Mike Scherer Christine Zhang The Great Divide 14 Abbie Necessary Chelsea Samson E-Week Celebrates Engineering 16 Faculty Advisor: (Not) Risky Business 17 Homeless but not Hopeless 18 Michael Miga, Ph.D. Vanderbilt BME is on the Move! 19 On the Cover Cover image is a functional MRI of the human visual cortex taken on a 7 Tesla MR imaging unit. ~ Courtesy of John C. Gore, professor of biomedical engineering, physics and molecular physiology and bio- physics, and radiology and radiological sciences at Vanderbilt University Page 3 Volume 1, Issue 2 Letter from the president I’m sure you will agree with me when I say this fall semester has flown by. I hope your semester has been both productive and fun. The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) at Vanderbilt University is a student run undergraduate organization open to all undergraduates studying biomedical engineering. Our mission is twofold: to promote the growth of biomedical engineering knowledge and its utilization and to bring together students and industry leaders to develop key contacts and relationships for the future. While we are a relatively new society, we have made great strides in the past two years and in the process have developed many goals to pass on to future chapter members. -

Red Dot Show Locatiotts of Reported Thefts Attd R~Bberies Sittce the Begittttittg of Fa" Se",Ester 2 September 16, 2008

Tuesday, September 16, 2008 Volume 135, Issl;Je 3 Red dot show locatiotts of reported thefts attd r~bberies sittce the begittttittg of Fa" Se",ester 2 September 16, 2008 2 News 14 Editorial 15 Opinion 17 Mosaic 21 Fashion Forward 27 Classifieds 28 Sports 29 Sports Commentary THE REVIEWlRicky Ber! Students play with German Shepherd puppies being sold on the Green. Check out our Web site for breaking news, blogs and more. www.udreview.com Cover map courtesy of Google Maps. Locations THE REVIEW/Steven Gold THE REVIEW/Steven Gold The band performs in front ofthe stadium's The Resident Student Association handed out plastic of crimes from University of Delaware Public new video screen. bags for recycling at Saturday's game. Safety and Newark Police Department. The Review is published once weekly every Tuesday of the school year, except Editor in Chief Graphics Editor Managing Mosaic Editors during Winter and Summer Sessions. An exclusive, online edition is published every Laura Dattaro Katie Smith Caitlin Birch, Larissa Cruz Friday. Our main office is located at 250 Perkins Student Center, Newark, DE 19716. Executive Editor Web site Editor Features Editors Brian Anderson . 9uentin Coleman Sabina Ellahi, Am;: Prazniak If you have questions about advertising or news content, see the listings below. Entertainment Editors Editori!ll Editors Ted Simmons, James Adams Smith Managing News Editors Sammi Cassin, Caitlin Wolters delaware UNdressed Columnist Jennifer Heine, Josh Shannon Alicia Gentile Cartoonist Administrative News Editor Display Advertising -

The History of Rock Music: the 2000S

The History of Rock Music: The 2000s History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2006 Piero Scaruffi) Clubbers (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Electroclash TM, ®, Copyright © 2008 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The "electroclash" movement was basically a revival of the dance-punk style of the new wave. It was New York dj Lawrence "Larry Tee" who coined the term, and the first Electroclash Festival was held in that city in 2001. However, the movement had its origins on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. One could argue that electroclash was born with Space Invaders Are Smoking Grass (1997), released by Belgian dj Ferenc van der Sluijs under the moniker I-f. At about the same time German house dj Helmut-Josef "DJ Hell" Geier was promoting a scene in Berlin that was basically electroclash. Another forerunner was French dj Caroline "Miss Kittin" Herve', who had recorded the EP Champagne (1998), a collaboration with Michael "The Hacker" Amato that included the pioneering hit 1982. The duo joined the fad that they had pioneered with First Album (2001). Britain was first exposed to electroclash when Liverpool's Ladytron released He Took Her To A Movie (1999), that was basically a cover of Kraftwerk's The Model. Next came Liverpool's Robots In Disguise with the EP Mix Up Words and Sounds (2000). -

The Mashup As Resistance? a Critique of Marxist Framing in the Digital Age

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 The am shup as resistance?: A critique of Marxist framing in the digital age Adam Rugg University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Rugg, Adam, "The ashm up as resistance?: A critique of Marxist framing in the digital age" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2173 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mashup as Resistance? A Critique of Marxist Framing in the Digital Age by Adam Rugg A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D Andrew Berish, Ph. D Date of Approval: July 10, 2009 Keywords: Hegemony, Girl Talk, Consumer Empowerment, Remix, Copyright © Copyright 2009 , Adam Rugg Dedication I would like to dedicate this to my mom, my dad, and Randy, all who supported me and made it possible for me to pursue my academic goals. Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction 1 Chapter One: A Critique of Marxist Framing of the Mashup 10 Chapter Two: Girl Talk: A Case Study 25 Chapter Three: The Current Media Landscape 42 An Open Practice 44 Sanctioned Mixing 47 Consumers as Workers 51 i The Mashup as Resistance? A Critique of Marxist Framing of the Digital Age Adam Rugg ABSTRACT This thesis critiques contemporary scholarly approaches to the modern musical mashup that rely on outdated and over-generalized Marxist frameworks. -

UMBC Greeks Come Together for Philanthropy Intimate Interview With

14 Arts [email protected] UMBC Greeks come together for philanthropy Zak Bratcher with Phi Mu,” said Steve Gilmore, a RETRIEVER STAFF Pi Kappa Phi member, on Thursday night. “It’s an event in teamwork, “Are you guys ready for some live and we’re really excited.” music?” Gilmore, a senior and former Alex Applebaum, a former UMBC Student Government Association student and member of Pi Kappa Phi president, said that Pi Kappa Phi Fraternity, kicked the night off in has held Rock for Push benefit con- fine style, warming up the crowd up certs below Flat Tuesdays in the in the University Center ballroom Commons the past two semesters. during Thursday evening’s Phi Is for Because of the partnership with Phi Philanthropy concert. Applebaum Mu, the event was shifted to the was one of five musical acts that larger venue in the UC. performed as part of the night-long Each of the five musical acts fundraising festivities. played for approximately half an The fundraiser was part of a hour. As mentioned, Applebaum partnership between UMBC Greek opened the event playing his brand organizations Pi Kappi Phi and Phi of acoustic pop-rock, including Mu Fraternity for Women to raise a cover of Dave Matthews Band’s money for charitable donation. “Tripping Billies.” “Last semester, we did Rock for T3, a harmonizing, folksy, acous- Push,” said Corey Jennings, a Pi tic pairing of UMBC junior Matthew Kappi Phi member. “We wanted to Polonchak and his twin brother Mi- make it bigger and better.” chael, performed next. They were Jennings, a junior, co-chaired the followed by last minute addition Phi Is for Philanthropy concert along The Town Criers, the rock-n-roll with Phi Mu’s Chantelle Walsh. -

Girl Talk Announces First North American Tour in Eight Years

February 10, 2020 For Immediate Release Girl Talk Announces First North American Tour in Eight Years Photo Credit - Joey Kennedy Girl Talk, aka Pittsburgh’s Gregg Gillis, is excited to announce his first North American tour in eight years. Throughout the past two decades, Girl Talk has been known for his wholly energetic, sweat soaked, confetti-covered live shows and festival performances. Once again, he will bring this exuberance across the states, playing Chicago’s Metro, Los Angeles’ Echoplex, the 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C., and more. A full list of dates can be found below and tickets go on sale later this week. Gillis built his reputation from his meticulous construction of sample-based music and specific style of genre-smashing, breakneck-paced party jams. With each Girl Talk album, from his breakout Night Ripper (2006) to Feed The Animals (2008) and his last, All Day (2010), his work has become increasingly detailed and complex. The last several years have seen Gillis focusing on collaborative work producing hip hop for some of his favorite rap artists. In 2014, he and Philadelphia’s Freeway released the "Broken Ankles” EP, and since then, Gillis has steadily earned an impressive list of production credits and collaborations with his artistic contemporaries, including Wiz Khalifa, T-Pain, Tory Lanez, Young Nudy, Bas, Cozz, Erick The Architect (from Flatbush Zombies), Smoke DZA, and Don Q. As Noisey so aptly describes him, "The tracks he's released over the last year show, more than anything, that Gillis is adaptable as a producer. The people he's worked with are about as different as you can get in the wider rap world, but no matter the circumstance, he's been able to find palettes that work for each of their voices. -

Amen to That Sampling and Adapting the Past

Amen to That Sampling and Adapting the Past • Steve Collins • Respond to this Article • Volume 10 • Issue 2 • May 2007 1In 1956, John Cage predicted that “in the future, records will be made from records” (Duffel, 202). Certainly, musical creativity has always involved a certain amount of appropriation and adaptation of previous works. For example, Vivaldi appropriated and adapted the “Cum sancto spiritu” fugue of Ruggieri’s Gloria (Burnett, 4; Forbes, 261). If stuck for a guitar solo on stage, Keith Richards admits that he’ll adapt Buddy Holly for his own purposes (Street, 135). Similarly, Nirvana adapted the opening riff from Killing Jokes’ “Eighties” for their song “Come as You Are”. Musical “quotation” is actively encouraged in jazz, and contemporary hip-hop would not exist if the genre’s pioneers and progenitors had not plundered and adapted existing recorded music. Sampling technologies, however, have taken musical adaptation a step further and realised Cage’s prediction. Hardware and software samplers have developed to the stage where any piece of audio can be appropriated and adapted to suit the creative impulses of the sampling musician (or samplist). The practice of sampling challenges established notions of creativity, with whole albums created with no original musical input as most would understand it—literally “records made from records.” 2Sample-based music is premised on adapting audio plundered from the cultural environment. This paper explores the ways in which technology is used to adapt previous recordings into new ones, and how musicians themselves have adapted to the potentials of digital technology for exploring alternative approaches to musical creativity. -

Get a License Or Don't Sample: Using Examples from Popular Music To

Harvard Journal of Law & Technology Volume 29, Number 2 Spring 2016 GET A LICENSE OR DON’T SAMPLE: USING EXAMPLES FROM POPULAR MUSIC TO RAISE NEW QUESTIONS ABOUT THE BRIDGEPORT V. DIMENSION FILMS HOLDING Daniel Esannason* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 551 II. PROTECTING THE CREATORS OF MUSIC ....................................... 552 III: EARLY ATTITUDES TOWARDS SOUND RECORDINGS .................. 554 IV. CHANGE IN TECHNOLOGY, CHANGE IN ATTITUDE ..................... 555 V. THE ADVENT OF SAMPLING AS A MUSIC PRODUCTION TECHNIQUE ................................................................................... 557 VI. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE BRIDGEPORT HOLDING .................... 558 VII. HOW MUSIC IS MADE TODAY ................................................... 561 VIII. CONCLUSION ............................................................................ 565 I. INTRODUCTION In the 1900s, advancements in music reproduction technology gave rise to two major copyright questions: (1) should sound record- ings be protected and (2) if so, to what degree? These questions stemmed from two considerations: (1) what promotes the progress of the useful arts and (2) what decisions need to be made in light of technological advancements that facilitate the reproduction of music? Today, new techniques of producing music present novel varia- tions on these questions. Specifically, how do music software pro- grams alter our conception of how sound recordings are produced, and to what extent, if any, should music producers be able to sample sound recordings constructed from pre-made loops? This Note is an attempt to answer these questions. Part II outlines the purpose of cop- yright law and how it applies to music. Part III discusses how the 1909 Copyright Act and early 20th century cases reflected initial atti- tudes asserting that sound recordings should not be protected. Part IV * Harvard Law School, J.D. -

Adapting Copyright for the Mashup Generation

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 † Koret Professor of Law and Director, Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, University of California at Berkeley, School of Law. I thank my sons Dylan and Noah, Peter DiCola, Kembrew McLeod, Gregg Gillis, DJ Guzie, and DJ Solarz for inspiration and background about mashup culture. I also thank Mark Avsec, Jane Ginsburg, Eric Goldman, Molly Van Houweling, David Nimmer, Dotan Oliar, Sean Pager, and participants at the Berkeley Law IP Scholarship Seminar, Berkeley Law Faculty Seminar, and Fifth Annual Internet Law Work-in-Progress Conference for comments. -

Fair Use, Girl Talk, and Digital Sampling: an Empirical Study of Music Sampling's Effect on the Market for Copyrighted Works

Oklahoma Law Review Volume 67 Number 3 2015 Fair Use, Girl Talk, and Digital Sampling: An Empirical Study of Music Sampling's Effect on the Market for Copyrighted Works William M. Schuster II Vinson & Elkins, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation William M. Schuster II, Fair Use, Girl Talk, and Digital Sampling: An Empirical Study of Music Sampling's Effect on the Market for Copyrighted Works, 67 OKLA. L. REV. (2015), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol67/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oklahoma Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fair Use, Girl Talk, and Digital Sampling: An Empirical Study of Music Sampling's Effect on the Market for Copyrighted Works Cover Page Footnote Mike Schuster, [email protected], is a patent attorney who is licensed to practice law in the State of Texas. Schuster obtained his LL.M. in intellectual property/trade regulation from the New York University School of Law and his J.D., summa cum laude, from South Texas College of Law. The opinions expressed in this Article are those of the Author alone and should not be imputed to his employer or any of its clients.