Digital Sampling of Music and Copyrights: Is It Infringement, Fair Use, Or Should We Just Flip a Coin?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

A Remix Manifesto

An Educational Guide About The Film In RiP: A remix manifesto, web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor explores issues of copyright in the information age, mashing up the media landscape of the 20th century and shattering the wall between users and producers. The film’s central protagonist is Girl Talk, a mash‐up musician topping the charts with his sample‐based songs. But is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy? Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig, Brazil’s Minister of Culture, Gilberto Gil, and pop culture critic Cory Doctorow also come along for the ride. This is a participatory media experiment from day one, in which Brett shares his raw footage at opensourcecinema.org for anyone to remix. This movie‐as‐mash‐up method allows these remixes to become an integral part of the film. With RiP: A remix manifesto, Gaylor and Girl Talk sound an urgent alarm and draw the lines of battle. Which side of the ideas war are you on? About The Guide While the film is best viewed in its entirety, the chapters have been summarized, and relevant discussion questions are provided for each. Many questions specifically relate to music or media studies but some are more general in nature. General questions may still be relevant to the arts, but cross over to social studies, law and current events. Selected resources are included at the end of the guide to help students with further research, and as references for material covered in the documentary. This guide was written and compiled by Adam Hodgins, a teacher of Music and Technology at Selwyn House School in Montreal, Quebec. -

Frank Musarra Multimedia Artist and Technologist Born in Cleveland OH, 1981 BA, Bard College, Annandale-On-Hudson, NY, 2003 Lives and Works in Brooklyn NY

Frank Musarra Multimedia Artist and Technologist Born in Cleveland OH, 1981 BA, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY, 2003 Lives and works in Brooklyn NY Selected Multimedia Fabrications 2019: Kunsthalle Basel, Dora Budor: ‘The Preserving Machine’, Basel, Switzerland ● Raspberry Pi & Arduino microcontroller programming, biomechanical flying bird controlled via bluetooth and custom javascript / node.js code. Flight pattern based on data taken from Beethoven's 9th symphony. Musical data was parsed with Ableton Live and a custom Max/MSP patch, data translated into Javascript. Nike, ‘Nike Soho: Department of Unimaginable’, New York, NY ● Kinetic sculpture commission for mixed media installation and window display at Nike’s 5-story Soho retail location. 3D printed components, Arduino microcontroller programming, LEDs, GPU liquid cooling system pumps and fans, UV sensitive paint and filament, reclaimed e-waste. Esther Klein Gallery, Laura Splan: ‘Remote Entanglements’, ‘Contested Territories’, Philadelphia, PA ● Designed, programmed, and fabricated custom networked sculptures. Modified fan, wireless Raspberry Pi control, adjusting wind speed in real time to data from a biological laboratory. Twitter actuated lab mixer, IOT microcontroller, networked control. Wonderspaces Gallery, Foo/Skou: ‘Harmony of Spheres’, San Diego, CA ● Prototyping, development and fabrication of an interactive light and sound sculpture. Eighty-one wooden spheres coated in touch-sensitive conductive paint triggering eighty-one audio loops of choral vocalists and eighty-one LED spotlights. Interactive spatial playback on eighteen separate audio channels. Arduino microcontroller programming, capacitive touch sensor, polyphonic audio module, programmable LEDs. Amaro Montenegro, ‘Zest’s Lab’, Brooklyn Bar Convention, Brooklyn, NY ● Interactive sculpture commission for immersive theater performance / experiential marketing campaign. Mixed media, custom audio synthesizer, lighting, peristaltic liquid pumps for elaborate cocktail mixing device. -

Night Ripper Game Free Download Night Ripper Game Free Download

night ripper game free download Night ripper game free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66afcb849cee8498 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Night Watch Puppet Combo Download Free. Posted: (8 days ago) May 01, 2020 · Download Minecraft Map. Download : Night Watch How to install Minecraft Maps on Java Edition. Inspired by a Puppet Combo game : NIGHT WATCH Texture Pack and map made by : Trevencraftxxx ( me :D ) Progress: 100% complete: Tags: Horror. Night. Creepy. Puzzle. Challenge Adventure. Nightwatch. 2. Night Watch | Puppet Combo Wiki | Fandom. Posted: (5 days ago) Night Watch is a 2019 horror game developed by Puppet Combo. The game is available for download on Puppet Combo's Patreon1. 1 Summary 1.1 Outcome 1 1.2 Outcome 2 1.3 Outcome 3 2 Trivia 3 Gallery 4 References The game follows a park ranger named Jim who was assigned on watch duty on top of the tower in the middle of the park, where he specifically has to check for fires and guide any … Night Watch is Out! Park Ranger HORROR - Puppet Combo. -

The Hood Internet Mixes It Up

CROSSFADER (//CROSSFADER.FM/) ARCHIVE (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/ARCHIVE/) APPS (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/APPS/) DJZ (http://www.djz.com/) CROSSFADER (//CROSSFADER.FM/) ARCHIVE (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/ARCHIVE/) APPS (HTTP://WWW.DJZ.COM/APPS/) EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW INTERVIEW: THE HOOD INTERNET MIXES IT UP Kim Reyes • SEP 11, 2013 Tweet 1 Aaron Brink and Steve Reidell decided to break out into the mash-up music scene under the moniker The Hood Internet (http://www.djz.com/tag/the-hood- internet) in a time when the genre was hot. Brink and Reidell, known by their DJ names ABX and STV SLV, have been releasing free mash-up songs and mixes on their website since 2007. What began as an internet project has transformed overtime to incorporate live DJ sets and a studio album of original tracks. Before taking the stage at the San Francisco venue The Independent on August 17, Reidell briefly explained the history of how The Hood Internet came to be. “ABX and I had a history of experimenting with looped-based software, just kind of making fun beats out of songs for our friends to rap on. The internet at the time seemed to be really receptive to mashups and I think we wanted to approach them with a little different twist.” In order to set themselves apart from other mash-up peers like Girl Talk (http://illegal-art.net/girltalk/), The Hood Internet decided to curate music by fusing rap and hip-hop with indie and electronic music. These songs were not necessarily chosen for their mainstream popularity, but were tracks chosen from Brink and Reidell’s own personal library of music. -

Sampling the Circuits: the Case for a New Comprehensive Scheme for Determining Copyright Infringement As a Result of Music Sampling

Washington University Law Review Volume 89 Issue 5 2012 Sampling the Circuits: The Case for a New Comprehensive Scheme for Determining Copyright Infringement as a Result of Music Sampling John S. Pelletier Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation John S. Pelletier, Sampling the Circuits: The Case for a New Comprehensive Scheme for Determining Copyright Infringement as a Result of Music Sampling, 89 WASH. U. L. REV. 1135 (2012). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol89/iss5/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SAMPLING THE CIRCUITS: THE CASE FOR A NEW COMPREHENSIVE SCHEME FOR DETERMINING COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT AS A RESULT OF MUSIC SAMPLING INTRODUCTION Music sampling continues to be the linchpin of a variety of musical styles including rap, hip-hop, house, and dance music, and has even become prevalent in rock music.1 The practice of sampling involves taking pre-existing sound recordings and using portions of those recordings as elements in a new musical composition.2 The amount of the work sampled can range from taking the entire ―hook‖ or chorus/refrain from a musical composition to smaller elements, such as a riff or even one or two notes or words.3 Music sampling, as it pertains to copyright law and copyright licensing, is a real and current issue. -

T Pain Oblivion Album Download ALBUM: T-Pain – Oblivion

t pain oblivion album download ALBUM: T-Pain – Oblivion. Stream And “Listen to ALBUM: T-Pain – Oblivion” “Fakaza Mp3“ 320kbps flexyjams cdq Fakaza download datafilehost torrent download Song Below. Release Date: November 17, 2017. Copyright: ℗ 2017 RCA Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment. Tracklist 1. Who Died 2. Classic You (feat. Chris Brown) 3. Straight 4. That’s How It Go 5. No Rush 6. Pu$$y on the Phone 7. Textin’ My Ex (feat. Tiffany Evans) 8. May I (feat. Mr. Talkbox) 9. I Told My Girl (feat. Manny G) 10. She Needed Me 11. Your Friend 12. Cee Cee From DC (feat. Wale) 13. Goal Line (feat. Blac Youngsta) 14. 2 Fine (feat. Ty Dolla $ign) 15. That Comeback 16. Second Chance (Don’t Back Down) [feat. Roberto Cacciapaglia] Listen: T-Pain New Album “Oblivion” T-Pain new album Oblivion is now available for streaming and download on iTunes/Apple Music. The project arrives six years after his previous album rEVOLVEr . Oblivion comes with 16 tracks with a couple guest verses from the likes of Wale, Ty Dolla $ign, Chris Brown, Tiffany Evans, Talkbox, Manny G, Blac Youngsta among others. Youngsta can be found on the previously released single “Goal Line” while singer Tiffany Evans is featured on another previously released single “Textin My Ex.” The auto-tune rapper first announced the project earlier this year and after a few delays its finally here. During an interview with XXL in August, T-Pain said Oblivion would be his final album on his deal with RCA. He also noted that majority of the project was produced by Dre Moon. -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities. -

BMES V1 No2 Version2

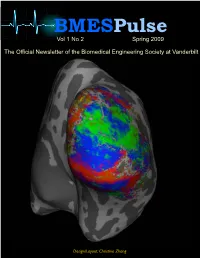

BMESPulse Vol 1 No 2 Spring 2009 The Official Newsletter of the Biomedical Engineering Society at Vanderbilt Design/Layout: Christine Zhang INSIDE THIS ISSUE Letter from the President 3 Editor: Christine Zhang Meet the BMES Officers 4 Contributing Writers: Pathfinder Therapeutics 6 A traipse into Law 8 Catherine Ruelens Paul Guillod Girl Talk 10 Yina Dong (UCSD) Mike Scherer Christine Zhang The Great Divide 14 Abbie Necessary Chelsea Samson E-Week Celebrates Engineering 16 Faculty Advisor: (Not) Risky Business 17 Homeless but not Hopeless 18 Michael Miga, Ph.D. Vanderbilt BME is on the Move! 19 On the Cover Cover image is a functional MRI of the human visual cortex taken on a 7 Tesla MR imaging unit. ~ Courtesy of John C. Gore, professor of biomedical engineering, physics and molecular physiology and bio- physics, and radiology and radiological sciences at Vanderbilt University Page 3 Volume 1, Issue 2 Letter from the president I’m sure you will agree with me when I say this fall semester has flown by. I hope your semester has been both productive and fun. The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) at Vanderbilt University is a student run undergraduate organization open to all undergraduates studying biomedical engineering. Our mission is twofold: to promote the growth of biomedical engineering knowledge and its utilization and to bring together students and industry leaders to develop key contacts and relationships for the future. While we are a relatively new society, we have made great strides in the past two years and in the process have developed many goals to pass on to future chapter members. -

Red Dot Show Locatiotts of Reported Thefts Attd R~Bberies Sittce the Begittttittg of Fa" Se",Ester 2 September 16, 2008

Tuesday, September 16, 2008 Volume 135, Issl;Je 3 Red dot show locatiotts of reported thefts attd r~bberies sittce the begittttittg of Fa" Se",ester 2 September 16, 2008 2 News 14 Editorial 15 Opinion 17 Mosaic 21 Fashion Forward 27 Classifieds 28 Sports 29 Sports Commentary THE REVIEWlRicky Ber! Students play with German Shepherd puppies being sold on the Green. Check out our Web site for breaking news, blogs and more. www.udreview.com Cover map courtesy of Google Maps. Locations THE REVIEW/Steven Gold THE REVIEW/Steven Gold The band performs in front ofthe stadium's The Resident Student Association handed out plastic of crimes from University of Delaware Public new video screen. bags for recycling at Saturday's game. Safety and Newark Police Department. The Review is published once weekly every Tuesday of the school year, except Editor in Chief Graphics Editor Managing Mosaic Editors during Winter and Summer Sessions. An exclusive, online edition is published every Laura Dattaro Katie Smith Caitlin Birch, Larissa Cruz Friday. Our main office is located at 250 Perkins Student Center, Newark, DE 19716. Executive Editor Web site Editor Features Editors Brian Anderson . 9uentin Coleman Sabina Ellahi, Am;: Prazniak If you have questions about advertising or news content, see the listings below. Entertainment Editors Editori!ll Editors Ted Simmons, James Adams Smith Managing News Editors Sammi Cassin, Caitlin Wolters delaware UNdressed Columnist Jennifer Heine, Josh Shannon Alicia Gentile Cartoonist Administrative News Editor Display Advertising -

The History of Rock Music: the 2000S

The History of Rock Music: The 2000s History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2006 Piero Scaruffi) Clubbers (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Electroclash TM, ®, Copyright © 2008 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The "electroclash" movement was basically a revival of the dance-punk style of the new wave. It was New York dj Lawrence "Larry Tee" who coined the term, and the first Electroclash Festival was held in that city in 2001. However, the movement had its origins on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. One could argue that electroclash was born with Space Invaders Are Smoking Grass (1997), released by Belgian dj Ferenc van der Sluijs under the moniker I-f. At about the same time German house dj Helmut-Josef "DJ Hell" Geier was promoting a scene in Berlin that was basically electroclash. Another forerunner was French dj Caroline "Miss Kittin" Herve', who had recorded the EP Champagne (1998), a collaboration with Michael "The Hacker" Amato that included the pioneering hit 1982. The duo joined the fad that they had pioneered with First Album (2001). Britain was first exposed to electroclash when Liverpool's Ladytron released He Took Her To A Movie (1999), that was basically a cover of Kraftwerk's The Model. Next came Liverpool's Robots In Disguise with the EP Mix Up Words and Sounds (2000). -

Remixing Music Copyright to Better Protect Mashup Artists Kerri Eble

EBLE.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 3/29/2013 2:34 PM THIS IS A REMIX: REMIXING MUSIC COPYRIGHT TO BETTER PROTECT MASHUP ARTISTS KERRI EBLE Modern copyright law has strayed from its original purpose as set out in the Constitution and is ill-equipped to protect and foster new forms of artistic expression. Since the last major amendment to the Copyright Act, new art forms have arisen, particularly “mashup music.” This type of music combines elements of other artists’ songs with other sounds to create a new artistic work. Under modern copy- right law, various courts treat this type of music inconsistently, creat- ing uncertainty among mashup artists and stifling this new artistic ex- pression. In addition, copyright law, as applied to music, unduly favors primary artists, sacrificing the Copyright Clause’s focus on preserving the public domain. This Note discusses the history of mashup music and its increas- ing popularity in the United States, as well as the relevant history of copyright law. This Note then discusses current safe harbors that ex- ist under copyright law for secondary artists and analyzes why mashups do not fit within these safe harbors. This Note concludes by recommending that the fair use exception be expanded to protect mashup artists by adding a safe harbor for “recontextualized” or “re- designed” artworks. I. INTRODUCTION Everything is breaking down in a good way. Once upon a time . there was a line. You know, the edge of the stage was there. The performers are on one side. The audience is on the oth- er side, and never the twain shall meet.