Get a License Or Don't Sample: Using Examples from Popular Music To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

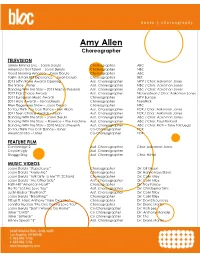

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

Summer Savage Challenge

S U M Awwwww SNAP. M Finish line, here we WELCOME E come! It's Week 4! R S A WE READY!! V TO WEEK 4 BRING IT ON! A G E L E T ' S G O O O O ! ! ! ! ! Y E S , I K N O W ! C O M P E T I T I O N ? H O W T O E N T E R C Did somebody say week We have leveled If you haven't submitted It's simple: H 4?? up...quarantine edition. Let's those before photos, 1.Take 3 before and A make sure that we don't go you've still got time! after photos (front, L back to what is "familiar". We side and back) Wow, time has literally @ have to continue to rise to a We will start collecting 2.Submit photos to L flown by. This is the last new level. perspective and s E after photos on Monday, [email protected] a week of our Summer discipline. r a May 4th. N Savage 30 day l o Now that we've improved G challenge. I am so glad I v Don't forget, best before our fitness life, what other e was able to share this E areas in your life need and after photos win a s experience with you. t improvement? PRIZE! y l e S U D I S C L A I M E R M M E Sara Lovestyle (Sara Hood) strongly recommends that you consult with your physician before beginning any exercise program. -

TABOO WORDS in the LYRICS of CARDI B on ALBUM INVASION of PRIVACY THESIS Submitted to the Board of Examiners in Partial Fulfillm

TABOO WORDS IN THE LYRICS OF CARDI B ON ALBUM INVASION OF PRIVACY THESIS Submitted to the Board of Examiners In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For Literary Degree at English Literature Department by PUTRI YANELIA NIM: AI.160803 ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SULTAN THAHA SAIFUDDIN JAMBI 2020 NOTA DINAS Jambi, 25 Juli 2020 Pembimbing I : Dr. Alfian, M.Ed…………… Pembimbing II : Adang Ridwan, S.S, M.Pd Alamat : Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora UIN STS Jambi Kepada Yth Ibu Dekan Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora UIN STS Jambi Di- Tempat Assalamu‟alaikum wr.wb Setelah membaca dan mengadakan perbaikan seperlunya, maka kami berpendapat bahwa skripsi saudari: Putri Yanelia, Nim. AI.160803 yang berjudul „“Taboo words in the lyrics of Cardi bAlbum Invasion of Privacy”‟, telah dapat diajukan untuk dimunaqosahkan guna melengkapi tugas - tugas dan memenuhi syarat – syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana strata satu (S1) pada Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora, UIN STS Jambi. Maka, dengan itu kami ajukan skripsi tersebut agar dapat diterima dengan baik. Demikianlah kami ucapkan terima kasih, semoga bermanfaat bagi kepentingan kampus dan para peneliti. Wassalamu‟alaikum wr.wb Pembimbing I Pembimbing II Dr. Alfian, M.Ed Adang Ridwan, S.S., M.Pd NIP: 19791230200604103 NIDN: 2109069101 i APPROVAL Jambi, July 25th 2020 Supervisor I : Dr. Alfian, M.Ed……………… Supervisor II :Adang Ridwan, M.Pd ………………… Address : Adab and HumanitiesFaculty .. …………State Islamic University ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, ,,,,,,,Sulthan Thaha Saifuddin Jambi. To The Dean of Adab and Humanities Faculty State Islamic University In Jambi Assalamu‟alaikum wr. Wb After reading and revising everything extend necessary, so we agree that the thesis entitled“Taboo Words in the Lyrics of Cardi b on Album Invasion of Privacy”can be submitted to Munaqasyah exam in part fulfillment to the Requirement for the Degree of Humaniora Scholar.We submitted it in order to be received well. -

Night Ripper Game Free Download Night Ripper Game Free Download

night ripper game free download Night ripper game free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66afcb849cee8498 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Night Watch Puppet Combo Download Free. Posted: (8 days ago) May 01, 2020 · Download Minecraft Map. Download : Night Watch How to install Minecraft Maps on Java Edition. Inspired by a Puppet Combo game : NIGHT WATCH Texture Pack and map made by : Trevencraftxxx ( me :D ) Progress: 100% complete: Tags: Horror. Night. Creepy. Puzzle. Challenge Adventure. Nightwatch. 2. Night Watch | Puppet Combo Wiki | Fandom. Posted: (5 days ago) Night Watch is a 2019 horror game developed by Puppet Combo. The game is available for download on Puppet Combo's Patreon1. 1 Summary 1.1 Outcome 1 1.2 Outcome 2 1.3 Outcome 3 2 Trivia 3 Gallery 4 References The game follows a park ranger named Jim who was assigned on watch duty on top of the tower in the middle of the park, where he specifically has to check for fires and guide any … Night Watch is Out! Park Ranger HORROR - Puppet Combo. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

Cardi B and City Girls Bring Black Girl Rap Magic to BET Experience | Vibe 7/5/19, 8�05 PM

Cardi B And City Girls Bring Black Girl Rap Magic To BET Experience | Vibe 7/5/19, 8)05 PM " MUSIC Videos New Releases Live Reviews Album Reviews Music Premieres ADVERTISEMENT Simple, fast and powerful. Completely free -… Getty Images Cardi B And City Girls Close Out The BET Experience With Black Girl Rap Magic June 23, 2019 - 8:37 pm by Taylor Crumpton ! https://www.vibe.com/2019/06/city-girls-cardi-b-bet-expereience-review Page 1 of 14 Cardi B And City Girls Bring Black Girl Rap Magic To BET Experience | Vibe 7/5/19, 8)05 PM ADVERTISEMENT Hip-hop is the nation’s most popular genre, from underground house parties in New York, where rappers and MCs would display their capabilities through a devilish delivery, worthy of snatching the breath from your body. Over the past thirty years, rappers have ascended into modern-day rock stars; sold out stadium tours, overt interactions with the law, and for City Girls and Cardi B; the assimilation of popular phrases like, “Okurrr”, and “Periodt” into America’s vernacular. Their cultural influence was felt among concertgoers on Saturday (June 22) at Staples Center for BET Experience as fans armies like the Bardi Gang and City Girls transformed the venue into an old school kickback, as they went word for word with their favorite rappers. Snatched waists, icy gold chains, furs, and the occasional twerk from a group of aunties, (they turned BET Experience into a millennial’s version of Girls Trip); featured fashions from the night resembled one of Cardi’s promotional shots for her Fashion Nova campaign. -

Riaa Gold & Platinum Awards

4/1/2016 — 4/30/2016 In April 2016, RIAA certified 48 Digital Single Awards and 20 Album Awards. Complete lists of all album, single and video awards dating all the way back to 1958 can be accessed at riaa.com. RIAA GOLD & APRIL 2016 PLATINUM AWARDS DIGITAL MULTI-PLATINUM SINGLE (6) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 4/29/2016 MY HOUSE FLO RIDA ATLANTIC RECORDS 2 3/17/2015 4/1/2016 CRUISE FLORIDA GEORGIA BMX 10 4/10/2012 LINE 4/15/2016 WHITE IVERSON POST MALONE REPUBLIC RECORDS 2 8/14/2015 4/29/2016 WORK RIHANNA WESTBURY ROAD 3 1/27/2016 ENTERTAINMENT/DISTRIBUTED BY ROC NATION 4/29/2016 WORK RIHANNA WESTBURY ROAD 2 1/27/2016 ENTERTAINMENT/DISTRIBUTED BY ROC NATION 4/7/2016 ROSES THE CHAINSMOKERS COLUMBIA 2 3/10/2015 DIGITAL PLATINUM SINGLE (12) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 4/27/2016 DON’T BRYSON TILLER RCA 1 5/20/2015 4/21/2016 LOVE YOU LIKE THAT CANAAN SMITH MERCURY NASHVILLE 1 7/21/2014 4/18/2016 ONE CALL AWAY CHARLIE PUTH ARTIST PARTNERS GROUP 1 8/21/2015 4/29/2016 AW NAW CHRIS YOUNG RCA RECORDS LABEL 1 5/21/2013 NASHVILLE 4/29/2016 YOU CHRIS YOUNG RCA NASHVILLE 1 7/12/2011 4/29/2016 GETTIN’ YOU HOME CHRIS YOUNG RCA NASHVILLE 1 2/5/2009 4/29/2016 WHO I AM WITH YOU CHRIS YOUNG RCA RECORDS LABEL 1 9/17/2013 NASHVILLE 4/29/2016 MY HOUSE FLO RIDA ATLANTIC RECORDS 1 3/17/2015 4/29/2016 2 PHONES KEVIN GATES BREAD WINNERS 1 11/6/2015 ASSOCIATION/ATLANTIC RECORDS 4/15/2016 I TOOK A PILL IN IBIZA MIKE POSNER ISLAND RECORDS 1 4/3/2015 4/29/2016 WORK RIHANNA WESTBURY ROAD E 1 1/27/2016 NTERTAINMENT/DISTRIBUTED BY ROC NATION 4/15/2016 SAY IT TORY LANEZ MAD LOVE/INTERSCOPE 1 7/31/2015 www.riaa.com GoldandPlatinum @RIAA @riaa_awards APRIL 2016 DIGITAL GOLD SINGLE (25) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. -

Bryson Tiller Returns with New Single and Visual for “Inhale” from His Forthcoming 3Rd Studio Album Due out This Fall Click Here to Watch

BRYSON TILLER RETURNS WITH NEW SINGLE AND VISUAL FOR “INHALE” FROM HIS FORTHCOMING 3RD STUDIO ALBUM DUE OUT THIS FALL CLICK HERE TO WATCH [September 3, 2020 – New York, NY] Today, chart-topping, multi-platinum selling, Grammy-Award nominated recording artist Bryson Tiller makes his official return with the release of his new single and visual for “Inhale” which will appear on his forthcoming third studio album out this fall via Trapsoul/RCA Records. Click HERE to listen/watch. “Inhale” which is produced by Dpat (Wiz Khalifa, Brent Faiyaz), continues with the introspective style that Tiller is known for while sampling SWV’s “All Night Long” and Mary J. Blige’s “Not Gon Cry.” The sensual and moody visual is directed by Tiller’s frequent collaborator Ro.Lexx. After treating fans to several releases on Souncloud, “Inhale” is the first official single release from Tiller following his critically acclaimed sophomore album, True To Self (2017), which topped the Billboard 200 albums chart upon release with Variety proclaiming it “one of the biggest records of the summer, if not the year.” Most recently Tiller has collaborated with Summer Walker for “Playing Games,” fellow Louisville native Jack Harlow for “Thru The Night,” Wale for “Love…Her Fault” and H.E.R. for “Could’ve Been” which earned the duo a Grammy nomination for R&B Performance in 2020. Listen/watch “Inhale” and keep an eye out for more from Bryson Tiller coming soon. Listen/Watch: “Inhale”: https://brysontiller.lnk.to/Inhale About Bryson Tiller: Bryson Tiller has captivated fans since his inception with the success of his 2015 debut album, T R A P S O U L. -

Jack Harlow & Chris Brown Team Up

JACK HARLOW & CHRIS BROWN TEAM UP IN MEXICO FOR “ALREADY BEST FRIENDS” MUSIC VIDEO WATCH HERE Directed by Ace Pro; filmed in Tulum, Mexico LOUISVILLE, KY RAPPER’S 4X-PLATINUM HIT “WHATS POPPIN” NOMINATED FOR BEST RAP PERFORMANCE AT THIS WEEKEND’S GRAMMY AWARDS SET TO MAKE SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE DEBUT ON MARCH 27TH WITH HOST MAYA RUDOLPH Critically acclaimed debut album THATS WHAT THEY ALL SAY out now Stream/Download here Photo Credit: Urban Wyatt Watch Jack’s must-see NPR Tiny Desk Concert: * * * ABOUT JACK HARLOW: Hailed by The FADER as a, “maverick rapper destined for legendary status,” 22-year-old, Louisville, KY native Jack Harlow has seen a meteoric rise since the release of his 4x-Platinum hit single, “WHATS POPPIN” (produced by Jetsonmade & Pooh Beatz,) in early 2020. The Generation Now/Atlantic Records rapper has consistently released a project each year, for the last 5 years, including 18 (2016), Gazebo (2017), Loose (2018), which received a Best Mixtape nomination at the 2019 BET Hip Hop Awards, Confetti (2019), featuring the Bryson Tiller-assisted “THRU THE NIGHT” and Sweet Action EP (2020), released on the same day as Harlow’s 22nd birthday. As one of 2020’s biggest break out stars, Harlow made his national television debut in February 2020 performing “WHATS POPPIN” on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. The song’s official remix, featuring Lil Wayne, DaBaby and Tory Lanez spent 13 straight weeks in the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at #2, while topping the charts at both Rhythm & Urban radio and peaking in the top 20 at Top 40 radio. -

Surprising 3-Pointer Sent JC to Regional Final

Saturday, February 13, 2021 The Commercial Review Portland, Indiana 47371 www.thecr.com $1 Defense argues Sheldon’s Stylz Trump did not incite Vote could come as early as today By ERIC TUCKER, LISA MASCARO and MARY CLARE JALONICK Associated Press WASHINGTON — Don - ald Trump’s impeachment lawyers accused Democrats of waging a campaign of “hatred” against the for - mer president as they sped through their defense of his actions and fiery words before the Jan. 6 insurrec - tion at the U.S. Capitol, hurtling the Senate toward a final vote in his historic trial. The defense team vigor - ously denied on Friday that Trump had incited the deadly riot and said his encouragement of follow - ers to “fight like hell” at a rally that preceded it was The Commercial Review/Bailey Cline routine political speech. Sheldon Ballinger’s new grooming and daycare service, Doggy Stylz & Inn, is open to dogs of all breeds and sizes. They played dozens of out- of-context clips showing In addition to the grooming station pictured above, she also has a garage for bathing and boarding dogs and a lobby Democrats, some of them complete with toys, treats and other items available for sale. senators now serving as jurors, also telling support - ers to “fight,” aiming to establish a parallel with Coldwater, Ohio, resident has opened a new Trump’s overheated rheto - ric. dog grooming and daycare business in Bryant “This is ordinarily politi - cal rhetoric that is virtually By BAILEY CLINE grooming table, time in high school at County $40. A touch-up, which includes indistinguishable from the The Commercial Review counters, cages Animal Clinic in Coldwater. -

AWARDS 10X DIAMOND ALBUM September // 9/1/16 - 9/30/16 CHRIS STAPLETON//TRAVELLER 2X MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM ADELE//25 AWARDS 10X DIAMOND ALBUM September // 9/1/16 - 9/30/16 CHRIS STAPLETON//TRAVELLER 2X MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM In September 2016, RIAA certified 87 Digital Single Awards and FIFTH HARMONY//7/27 23 Album Awards. All RIAA Awards GOLD ALBUM dating back to 1958, plus top tallies for your favorite artists, are available THOMAS RHETT//TANGLED UP at riaa.com/gold-platinum! PLATINUM ALBUM FARRUKO//VISIONARY SONGS PLATINO ALBUM www.riaa.com //// //// GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS SEPTEMBER // 9/1/16 - 9/31/16 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 23 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// 9/20/16 Hello Adele Pop Columbia/Xl Recordings 10/23/15 R&B/ 9/9/16 Exchange Bryson Tiller RCA 9/21/15 Hip Hop 9/28/16 Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Pop Schoolboy/Interscope 3/1/12 R&B/ Waverecordings/Empire/ 9/23/16 Broccoli D.R.A.M. 4/6/16 Hip Hop Atlantic Hollywood Records & Island 9/23/16 Cool For The Summer Demi Lovato Pop 7/1/15 Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 9/1/16 One Dance Drake Hip Hop 4/12/16 Republic Records Dance/Elec R&B/Hip Young Money/Cash Money/ 9/1/16 One Dance Drake Hop 4/12/16 Republic Records Dance/Elec R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 9/1/16 One Dance Drake Hip Hop 4/12/16 Republic Records Dance/Elec Work From Home 9/6/16 Fifth Harmony Pop Syco Music/Epic 2/26/16 Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign Future Feat.