The Tubular Groaning of Galactic Refrigerators Noise in the Age of Its Mechanical Reproducibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law Ledger

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW LEDGER VOLUME 1 WINTER 2009 NUMBER 1 MIXED SIGNALS: TAKEDOWN BUT DON’T FILTER? A CASE FOR CONSTRUCTIVE AUTHORIZATION * VICTORIA ELMAN AND CINDY ABRAMSON Scribd, a social publishing website, is being sued for copyright infringement for allowing the uploading of infringing works, and also for using the works themselves to filter for copyrighted work upon receipt of a takedown notice. While Scribd has a possible fair use defense, given the transformative function of the filtering use, Victoria Elman and Cindy Abramson argue that such filtration systems ought not to constitute infringement, as long as the sole purpose is to prevent infringement. American author Elaine Scott has recently filed suit against Scribd, alleging that the social publishing website “shamelessly profits” by encouraging Internet users to illegally share copyrighted books online.1 Scribd enables users to upload a variety of written works much like YouTube enables the uploading of video * Victoria Elman received a B.A. from Columbia University and a J.D. from Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she was a Notes Editor of the Cardozo Law Review. She will be joining Goodwin Procter this January as an associate in the New York office. Cindy Abramson is an associate in the Litigation Department in the New York office of Morrison & Foerster LLP. She recieved her J.D. from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in 2009 where she completed concentrations in Intellectual Property and Litigation and was Senior Notes Editor of the Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Morrison & Foerster, LLP. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Night Ripper Game Free Download Night Ripper Game Free Download

night ripper game free download Night ripper game free download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66afcb849cee8498 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Night Watch Puppet Combo Download Free. Posted: (8 days ago) May 01, 2020 · Download Minecraft Map. Download : Night Watch How to install Minecraft Maps on Java Edition. Inspired by a Puppet Combo game : NIGHT WATCH Texture Pack and map made by : Trevencraftxxx ( me :D ) Progress: 100% complete: Tags: Horror. Night. Creepy. Puzzle. Challenge Adventure. Nightwatch. 2. Night Watch | Puppet Combo Wiki | Fandom. Posted: (5 days ago) Night Watch is a 2019 horror game developed by Puppet Combo. The game is available for download on Puppet Combo's Patreon1. 1 Summary 1.1 Outcome 1 1.2 Outcome 2 1.3 Outcome 3 2 Trivia 3 Gallery 4 References The game follows a park ranger named Jim who was assigned on watch duty on top of the tower in the middle of the park, where he specifically has to check for fires and guide any … Night Watch is Out! Park Ranger HORROR - Puppet Combo. -

Metal Machine Music: Lou Reed Y La Hoja De Un Arbusto

Metal Machine Music: Lou Reed y la hoja de un arbusto Imagen: RCA. La línea que separa la genialidad de la tomadura de pelo es tan fina que a veces es interesante aproximarse a esa frontera para echar un vistazo a lo que sucede en sus inmediaciones y comprobar cómo las cosas a uno y otro lado son casi idénticas. Tuve ocasión de revisar una vez más esa vecindad hace algún tiempo, aunque quizá no el suficiente, cuando me sirvieron la hoja de un arbusto como parte de un menú degustación. Una hoja pequeña, sin acompañamientos, ni salsas, ni aliños, colocada en el centro de un enorme plato blanco e injusto. Una triste hoja y nada más. Todo un reto para cualquier comensal dotado del habitual arsenal de cubertería. Uno de mis acompañantes, al verse frente a la hoja, inició un discurso que defendía el carácter artístico del plato —y por extensión, del alarde culinario en general— por oposición a la simple nutrición. Preparar un puchero de lentejas con chorizo para ocho personas es cocinar, pero aquello que teníamos delante era arte. Cuántas vueltas habría dado el chef para crear aquella pieza. Cuántos experimentos habría llevado a cabo para componer su obra. Cuántos ingredientes habría tanteado hasta concluir que la hoja, por sí misma, era exactamente lo que buscaba. Lo fácil, lo mortal, habría sido servir un plato de lentejas. Su tesis era esa que defiende que la obra de arte excede de la necesidad humana. Si comer consistiese únicamente en alimentarse, no existiría la gastronomía. Solo la cocina. El planteamiento parecía razonable, pero a pesar del tranquilizador envoltorio teórico, mi plato seguía estando formado por una hoja tan insignificante que, en aquel momento, lo significaba todo. -

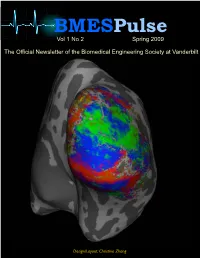

BMES V1 No2 Version2

BMESPulse Vol 1 No 2 Spring 2009 The Official Newsletter of the Biomedical Engineering Society at Vanderbilt Design/Layout: Christine Zhang INSIDE THIS ISSUE Letter from the President 3 Editor: Christine Zhang Meet the BMES Officers 4 Contributing Writers: Pathfinder Therapeutics 6 A traipse into Law 8 Catherine Ruelens Paul Guillod Girl Talk 10 Yina Dong (UCSD) Mike Scherer Christine Zhang The Great Divide 14 Abbie Necessary Chelsea Samson E-Week Celebrates Engineering 16 Faculty Advisor: (Not) Risky Business 17 Homeless but not Hopeless 18 Michael Miga, Ph.D. Vanderbilt BME is on the Move! 19 On the Cover Cover image is a functional MRI of the human visual cortex taken on a 7 Tesla MR imaging unit. ~ Courtesy of John C. Gore, professor of biomedical engineering, physics and molecular physiology and bio- physics, and radiology and radiological sciences at Vanderbilt University Page 3 Volume 1, Issue 2 Letter from the president I’m sure you will agree with me when I say this fall semester has flown by. I hope your semester has been both productive and fun. The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) at Vanderbilt University is a student run undergraduate organization open to all undergraduates studying biomedical engineering. Our mission is twofold: to promote the growth of biomedical engineering knowledge and its utilization and to bring together students and industry leaders to develop key contacts and relationships for the future. While we are a relatively new society, we have made great strides in the past two years and in the process have developed many goals to pass on to future chapter members. -

Red Dot Show Locatiotts of Reported Thefts Attd R~Bberies Sittce the Begittttittg of Fa" Se",Ester 2 September 16, 2008

Tuesday, September 16, 2008 Volume 135, Issl;Je 3 Red dot show locatiotts of reported thefts attd r~bberies sittce the begittttittg of Fa" Se",ester 2 September 16, 2008 2 News 14 Editorial 15 Opinion 17 Mosaic 21 Fashion Forward 27 Classifieds 28 Sports 29 Sports Commentary THE REVIEWlRicky Ber! Students play with German Shepherd puppies being sold on the Green. Check out our Web site for breaking news, blogs and more. www.udreview.com Cover map courtesy of Google Maps. Locations THE REVIEW/Steven Gold THE REVIEW/Steven Gold The band performs in front ofthe stadium's The Resident Student Association handed out plastic of crimes from University of Delaware Public new video screen. bags for recycling at Saturday's game. Safety and Newark Police Department. The Review is published once weekly every Tuesday of the school year, except Editor in Chief Graphics Editor Managing Mosaic Editors during Winter and Summer Sessions. An exclusive, online edition is published every Laura Dattaro Katie Smith Caitlin Birch, Larissa Cruz Friday. Our main office is located at 250 Perkins Student Center, Newark, DE 19716. Executive Editor Web site Editor Features Editors Brian Anderson . 9uentin Coleman Sabina Ellahi, Am;: Prazniak If you have questions about advertising or news content, see the listings below. Entertainment Editors Editori!ll Editors Ted Simmons, James Adams Smith Managing News Editors Sammi Cassin, Caitlin Wolters delaware UNdressed Columnist Jennifer Heine, Josh Shannon Alicia Gentile Cartoonist Administrative News Editor Display Advertising -

2013/2014 Mit 2013 Geht Ein Jahr Zu Ende, Das

2013/2014 mit 2013 geht ein jahr zu ende, das ich - trotz anfaenglich suboptimaler gesundheitlicher form - ueberaus positiv in erinnerung behalten werde: viel freude in der familie, schoene sommertage in spanien, italien und daheim sowie zuletzt auch wieder erfreulich viele gelungene unternehmungen im freundeskreis. auf mein berufliches jahr 2013 habe ich bereits in einem separaten beitrag zurueckgeblickt. desweiteren konnte ich mich im vergangenen jahr ueber einen konstanten strom neuer guter musik, eine reihe spannende buecher und einige wenige im kino gesehene filme freuen, die ich hier zu den bewaehrten jahresbestenlisten zusammengestellt habe. mit der frage, was 2014 kulturell auf uns zukommt, habe ich mich bereits mit meinem mix '10 fuer 2014' beschaeftigt. auch jenseits der newcomer schickt sich das neue jahr an, vielversprechend zu werden: schon im januar werden neue platten im januar von bruce springsteen, broken bells, rosanne cash, katy b, und maximo park erscheinen. in dem monaten danach folgen zudem neue werke von tinariwen, neneh cherry, st. vincent, elbow, kaiser chiefs, toni braxton und ernst molden & willi resetarits. auch im nebenstehenden konzertkalender finden sich bereits eine reihe von eintraegen, die fuer nicht unerhebliche vorfreude sorgen. neue buecher gibt es 2014 u.a. von martin suter, hanif kureishi, und michel houellebecq. und meinem vorsatz, kuenftig wieder oefter ins kino zu gehen, duerften die angekuendigten neuen filme von wes anderson, mike leigh, anton corbijn, fatih akin, luc besson, und michael winterbottom vorschub leisten. ich gehe somit in aufgeraeumter stimmung ins neue jahr und wuensche uns allen ein gutes 2014, viel freude, gesundheit und jede menge schoener erlebnisse! beruflicher jahresrueckblick der im letzten jahr begonnenen tradition folgend, will ich einmal mehr an dieser stelle auf die vergangenen zwoelf monate in beruflicher hinsicht zurueckblicken. -

A FICTION BROOKLYN ACADEMY of MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer

Brooklyn Academy of Music SONGS FOR'DRELLA -A FICTION BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer BAM Opera House November 29 - December 3, 1989 presents SONGS FOR 'DRELLA -A FICTION Music and Lyrics by Lou Reed and John Cale Set Design, Photography and Scenic Projections by Lighting Design by JEROME SIRLIN ROBERT WIERZEL Co-commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music NEXT WAVE Festival and The Arts at St. Ann's Joseph V. Melillo, Director, NEXT WAVE Festival SONGS FOR 'DRELLA-A FICTION Songs for 'Drella-a fiction is a brief musical look at the life of Andy Warhol and is entirely fictitious. We start with Andy growing up in a Sinalltown-"There's no Michelangelo coming from Pittsburgh." He comes to New York and follows the customs of"Open House" both in'his apartments and the Factory. "It's a Czechoslovakian custom my mother passed onto meltheway to makefriends Andyis to invite them upfor tea." He travels around the world and is in his words "Forever Changed." He knows the importance of people and money in the art world ["Style It Takes"] and follows his primary ethic, "Work-the most~portantthing is work." He can copy the classicists but feels "the trouble with classicists, they look at a tree/that's all they see/they paint a tree..." , Andy wished we all had the same "Faces and Names." He becomes involved with movies-"Starlight." He is interested in repetitive images-"I love images worth repeating••.see them with a different feeling." The mor tality rate at the Factory is rather high and some blame Andy-"Itwasn't me who shamed you..." The open house policy leads to him being shot ["I Believe"] and a new, locked door approach at the Factory causes him to wonder, "...if I have to live in fear/ where willI get my ideas...will I slowly Slip Away?" One night he has a dream, his relationships change..."A Nobody Like You." He dies recovering from a gall bladder operation. -

February 13, 1979

We cBtbeze Vol. SS Tiicsdav Kehruarv i:t. l!»7!» .lames Madison University, llurrisonburg. Virginia No. m 10,000 students by '90 proposed Four options considered Rv .11 LIF SI MMFRS An enrollment of 10,330 by 1989-90 has been proposed by a James Madison University administrative committee. This is 1.635 more students than allowed under an an enrollment projection approved by the State Council for Higher Education in Virginia (SCHEV) in December and 2.404 more students than presently enrolled. JMU currently has an enrollment of 7,926 students and the State Council has approved an enrollment of 8,695 by the end of the 1980's. The university is seeking to increase the approved projection and a committee of the-Planning and Development Commission has compiled four options for SCHEV to consider. All four options list enrollments exceeding the current limit. The highest projection is 10,330 by 1989-90. All state colleges and universities in Virginia project enrollments each biennium (two-year period). JMU has exceeded its approved projection each year, according to Dr. William Jackameit. director ofUnstitutional research here. In the past. SCHEV has always cut the projected enrollment figures JMU has presented. However, projections for the next biennium (1980-82) were approved with no alterations. "We have demonstrated that we are going to have the students." Jackameit said. "SCHEV is finally realizing we can get the students." By exceeding SCHEV approved projections, JMU has run the risk of losing tuition money from the extra students. State budgets are based on the approved projection numbers and JMU has not been receiving state funds for the extra students. -

The History of Rock Music: the 2000S

The History of Rock Music: The 2000s History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2006 Piero Scaruffi) Clubbers (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Electroclash TM, ®, Copyright © 2008 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The "electroclash" movement was basically a revival of the dance-punk style of the new wave. It was New York dj Lawrence "Larry Tee" who coined the term, and the first Electroclash Festival was held in that city in 2001. However, the movement had its origins on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. One could argue that electroclash was born with Space Invaders Are Smoking Grass (1997), released by Belgian dj Ferenc van der Sluijs under the moniker I-f. At about the same time German house dj Helmut-Josef "DJ Hell" Geier was promoting a scene in Berlin that was basically electroclash. Another forerunner was French dj Caroline "Miss Kittin" Herve', who had recorded the EP Champagne (1998), a collaboration with Michael "The Hacker" Amato that included the pioneering hit 1982. The duo joined the fad that they had pioneered with First Album (2001). Britain was first exposed to electroclash when Liverpool's Ladytron released He Took Her To A Movie (1999), that was basically a cover of Kraftwerk's The Model. Next came Liverpool's Robots In Disguise with the EP Mix Up Words and Sounds (2000). -

Lou Reed's Adaptations and the Pain They Cause

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2014-03-17 I Get a Thrill from Punishment: Lou Reed's Adaptations and the Pain They Cause Jonathan B. Smith Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Smith, Jonathan B., "I Get a Thrill from Punishment: Lou Reed's Adaptations and the Pain They Cause" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 4012. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “I Get a Thrill from Punishment”: Lou Reed’s Adaptations and the Pain They Cause Jonathan Smith A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Carl Sederholm, Chair Kerry Soper Rob McFarland Department of Humanities, Classics and Comparative Literature Brigham Young University March 2014 Copyright © 2014 Jonathan Smith All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “I Get a Thrill from Punishment”: Lou Reed’s Adaptations and the Pain They Cause Jonathan Smith Department of Humanities, BYU Masters of Arts This paper explores two adaptations by rock musician Lou Reed of the Velvet Underground and Metal Machine Music fame. Reed has always been a complicated and controversial figure, but two of his albums—The Raven (2003), a collaborative theater piece; and Lulu (2011), a collaboration with heavy metal band Metallica—have inspired confusion and vitriol among both fans and critics. -

1. 101 Strings: Panoramic Majesty of Ferde Grofe's Grand

1. 101 Strings: Panoramic Majesty Of Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite 2. 60 Years of “Music America Loves Best” (2) 3. Aaron Rosand, Rolf Reinhardt; Southwest German Radio Orchestra: Berlioz/Chausson/Ravel/Saint-Saens 4. ABC: How To Be A Zillionaire! 5. ABC Classics: The First Release Seon Series 6. Ahmad Jamal: One 7. Alban Berg Quartett: Berg String Quartets/Lyric Suite 8. Albert Schweitzer: Mendelssohn Organ Sonata No. 4 In B-Flat Major/Widor Organ Symphony No. 6 In G Minor 9. Alexander Schneider: Brahms Piano Quartets Complete (2) 10. Alexandre Lagoya & Claude Bolling: Concerto For Classic Guitar & Jazz Piano 11. Alexis Weissenberg, Georges Pretre; Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 3 12. Alexis Weissenberg, Herbert Von Karajan; Orchestre De Paris: Tchaikovsky Concerto #2 13. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Gregorian Chant-Easter Processions 14. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Music At Notre Dame 1200-1375 Guillaume De Machaut 15. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Songs From Taverns & Chapels 16. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Te Deum/Jubilate Deo 17. Alfred Newman; Brass Of The Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra: Hallelujah! 18. Alicia De Larrocha: Grieg/Mendelssohn 19. Andre Cluytens; Paris Conservatoire Orchestra: Bizet 20. Andre Kostelanetz & His Orchestra: Columbia Album Of Richard Rodgers (2) 21. Andre Kostelanetz & His Orchestra: Verdi-La Traviata 22. Andre Previn; London Symphony Orchestra: Rachmaninov/Shostakovich 23. Andres Segovia: Plays J.S. Bach//Edith Weiss-Mann Harpsichord Bach 24. Andy Williams: Academy Award Winning Call Me Irresponsible 25. Andy Williams: Columbia Records Catalog, Vol. 1 26. Andy Williams: The Shadow Of Your Smile 27. Angel Romero, Andre Previn: London Sympony Orchestra: Rodrigo-Concierto De Aranjuez 28.