A Guide to Building Lasting Relationships in Mentoring Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

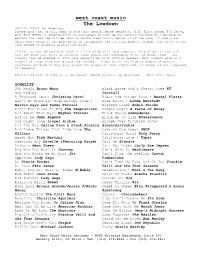

The Lowdown Songlist

west coast music The Lowdown SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, F/D Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm the band will be able to perform the song and will be able to locate sheet music, mp3 or CD of the song. If some cases where sheet music is not printed or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests. Please feel free to call us at the office should you have any questions. – West Coast Music SONGLIST: 24K Magic Bruno Mars Black Horse And A Cherry Tree KT 90s Medley Tunstall A Thousand Years Christina Perri Bless the Broken Road – Rascal Flatts Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Duet) Blue Bayou – Linda Ronstadt Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Brick House Commodores All Of Me John Legend Bring Me To Life Evanescence All Night Long Lionel Richie Bridge Over Troubled -

Special Pick of the Month E2 Energy: Growing Energy PROGRAMME 10 Game Night They Know Their Place but Have They Figured out the Game? PROGRAMME 1

Your In-Room Television Programme Guide MALAYSIA | MAY 2018 Special Pick Of The Month E2 Energy: Growing Energy PROGRAMME 10 Game Night They know their place but have they figured out the game? PROGRAMME 1 ROOM COPY ONLY KDN PP9343/10/2012(030542) Free to Guest Channel System 2 Channels 4 Channels 6 Channels 8 Channels Top Quality Movies Please check the number of Vision Four Channels and Documentaries - subscribed to by your Hotel. 24 Hours a Day Then follow the colour code. May 1, 5, 9, 13, 17, 21, 25, 29 *Jun 2 Channel 12am 3am 6am 9am 12pm 3pm 6pm 9pm Vision Four 1 5 49 41 25 21 15 31 1 Vision Four 2 6 50 42 26 22 16 32 2 Vision Four 3 7 51 43 27 23 9 33 3 Vision Four 4 8 52 44 28 24 10 34 4 Vision Four 5 1 53 45 37 17 11 35 5 Vision Four 6 2 54 46 38 18 12 36 6 Vision Four 7 3 55 47 39 19 13 29 7 Vision Four 8 4 56 48 40 20 14 30 8 May 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30 *Jun 3 Channel 12am 3am 6am 9am 12pm 3pm 6pm 9pm Vision Four 1 7 43 27 51 23 33 3 9 Vision Four 2 8 44 28 52 24 34 4 10 Vision Four 3 5 45 37 53 17 35 1 11 Vision Four 4 6 46 38 54 18 36 2 12 Vision Four 5 3 47 39 55 19 29 7 13 Vision Four 6 4 48 40 56 20 30 8 14 Vision Four 7 1 41 25 49 21 31 5 15 Vision Four 8 2 42 26 50 22 32 6 16 May 3, 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, 27, 31 *Jun 4 Channel 12am 3am 6am 9am 12pm 3pm 6pm 9pm Vision Four 1 1 37 53 45 11 5 35 17 Vision Four 2 2 38 54 46 12 6 36 18 Vision Four 3 3 39 55 47 13 7 29 19 Vision Four 4 4 40 56 48 14 8 30 20 Vision Four 5 5 25 49 41 15 3 31 21 Vision Four 6 6 26 50 42 16 4 32 22 Vision Four 7 7 27 51 43 9 1 33 23 Vision Four 8 8 28 52 44 10 2 34 24 May 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28 *Jun 1 Channel 12am 3am 6am 9am 12pm 3pm 6pm 9pm Vision Four 1 3 55 47 39 19 13 7 29 Vision Four 2 4 56 48 40 20 14 8 30 Vision Four 3 1 49 41 25 21 15 5 31 Vision Four 4 2 50 42 26 22 16 6 32 Vision Four 5 7 51 43 27 23 9 1 33 Vision Four 6 8 52 44 28 24 10 2 34 Vision Four 7 5 53 45 37 17 11 3 35 Vision Four 8 6 54 46 38 18 12 4 36 * In event of schedule overlap. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Go the Go the Distance Distance

GO THE DISTANCE A TWISTED TALE GO THE DISTANCE A TWISTED TALE What if Meg had to become a Greek god? JEN CALONITA Los Angeles • New York Copyright © 2021 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by Disney • Hyperion, an imprint of Buena Vista Books, Inc. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Disney • Hyperion, 125 West End Avenue, New York, New York 10023. Printed in the United States of America First Hardcover Edition, April 2021 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 FAC-020093-21050 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020946065 ISBN 978-1-368-06380-7 Visit disneybooks.com For Tyler and Dylan— Always go the distance. —J.C. PROLOGUE Some time ago . “Excuses! Excuses! You give the same ones every week!” “They’re not excuses, Thea! It’s the truth!” “Truth? You expect me to believe you leave this house every day and go to work?” Their voices echoed through the small home, inevitably reaching five-year-old Megara as she sat in the adjacent room at the window. She didn’t flinch as their argument grew louder and more heated. As cutting as their words might be, Megara didn’t understand them. Her parents’ arguments had become as common as the sun rising in the morning and the moon shining at night. Even her mother seemed to anticipate them coming now, like she could feel an impend- ing storm. -

09.03 Nycha Journalv3

Vol. 33, No. 9 First Class U.S. Postage Paid — Permit No. 4119, New York, N.Y. 10007 Septiembre 2003 CIENTOS ASISTEN A LA CAMINATA El Alcalde le Arnold Schwarzenegger Anuncia el ANUAL DE NIÑOS EN CENTRAL PARK Rinde Honores a Ganador Universitario de la un Empleado de NYCHA por Ir Competición del ‘Inner City Games’ Más Allá de sus Funciones uando las luces se apa- garon a las 4:11 pm el Cpasado 14 de agosto, en el comienzo del apagón más grande en la historia de los Estados Unidos, la coordinadora de la co- munidad, Myra Miller y 15 niños del Campamento de Verano del Centro Comunitario de Langston Hughes en Brooklyn recién habían regresado de su clase de entre- namiento de computación en la biblioteca local. Ms. Miller y sus empleados - la asistente comuni- a lluvia empapó las calles de la ciudad durante toda la semana, taria, Aisha Duckett y el ayudante pero el 6 de agosto del 2003, dejó de llover justo lo suficiente de servicio comunitario, Nereida Lpara que cientos de niños de los centros comunitarios de Martínez, estaban preparando los NYCHA a lo largo de la ciudad se reunieran en Central Park para la refrigerios para los niños cuando Segunda Caminata Anual de Niños de NYCHA. Estamos aquí para se apagó la electricidad. enseñarle a nuestras niños la importancia de la buena salud.” dijo el Los niños mayores, que van de presidente de NYCHA, Tino Hernández a la joven congregacion. los 6 a 12 años, fueron enviados a “Gracias por traer el sol. Ustedes son la razón por la cual el sol salió su casa. -

Hold It High (Cadence) on the Road Again the U.S

Hold It High (cadence) On the Road Again The U.S. Air Force Willie Nelson Brave Never Gonna Give You Up Sara Bareilles Rick Astley My Hero Home Foo Fighters Phillip Phillips Fight Song We Are The Champions Rachel Platten Queen Can’t Stop the Feeling (from Trolls) When Can I See You Again? (from Wreck-It Ralph) Justin Timberlake Owl City Dog Days Are Over Rise Up Florence & The Machine Andra Day Don’t You Worry ‘Bout A Thing (from SING) Holding Out For A Hero (from Footloose) Tori Kelly Bonnie Tyler Heroes (We Could Be) Firework Alesso, Tove Lo Katy Perry Daisies You’ll Always Find Your Way Back Home Katy Perry Hannah Montana How Far I’ll Go (from Moana) You Got It (The Right Stuff) Auli’I Cravalho New Kids On The Block Friends Are Family (from LEGO Batman Movie) Wild Things Oh, Hush!, Jeff Lewis, Will Arnett Alessia Cara 355th Force Support Squadron Marketing // Davis-Monthan Air Force Base Castle On The Hill Shake It Off Ed Sheeran Taylor Swift How Far We’ve Come Something To Be Proud Of Matchbox Twenty Montogomery Gentry I Will Wait I’m Still Standing Mumford & Sons Elton John Keep Your Head Up Go The Distance (from Hercules) Andy Grammar Roger Bart Leaving, On A Jet Plane Scars To Your Beautiful John Denver Alessia Cara Miles Apart We Know The Way (from Moana) Yellowcard Opetaia Foa’I, Lin-Manuel Miranda Into The Unknown (from Frozen 2) Part Of Me Idina Menzel, AURORA Katy Perry Budapest Just Around The Riverbend (from Pocahontas) George Ezra Judy Kuhn Boomerang I Will Survive JoJo Siwa Gloria Gaynor This Is Me (from The Greatest Showman) Tightrope (feat. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

DANNY COLLINS by Dan Fogelman

DANNY COLLINS by Dan Fogelman White Shooting Draft - 05/21/13 Blue Draft - 06/07/13 Pink Pages - 06/18/13 Yellow Pages - 06/20/13 Green Pages - 06/28/13 Goldenrod Pages - 07/01/13 Salmon Pages - 07/08/13 Buff Pages - 07/30/13 Cherry Pages - 08/01/13 This material is the property of Danny Collins Productions, LLC and access and use of this material is intended solely for use by Danny Collins Productions, LLC, its personnel and other authorized persons. Dissemination or disclosure of the material in any form to any unauthorized persons or the sale or copying of this material in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. 1. OVER BLACK we hear the sounds of a TURNTABLE turning on. We hear a NEEDLE drop. The record plays a SONG. The SONG is pure, innocent, and simple... the kind of thing great singer-songwriters are made of. TEXT: “The following is kind-of based on a true story a little bit.” The words are lifted away in a haze of CIGARETTE SMOKE. 1 INT. CHIME IN MAGAZINE OFFICES - DAY (1971) 1 We listen to the song as we pick up snapshots from an office of an early 70’s music magazine: - Cigarettes are smoked indoors, everywhere. Smoke wafts over cubicles, everywhere. - Women wear mini-skirts. Really “mini” mini-skirts. - Music POSTERS and SIGNAGE line cubicle walls. Hendrix. Dylan. Simon and a Jew-fro’d Garfunkel. - A poster of a young RICHARD NIXON. Someone has drawn a MUSTACHE on Nixon’s face as well as a “SPEECH BUBBLE” which reads “I’m an asshole.” - We hone in on a SINGLE CIGARETTE. -

Las Vegas, NV

Showbiz Las Vegas 2021 Overalls Rank Routine Dancer Studio Sapphire Minis Solo 1 Wind It Up Brooklyn Botello Murrieta Dance Project Sapphire Mini Duet/Trio 1 Lemonade The Pointe Dance Center Sapphire Mini Small Group 1 Everybody Wants To Be A Cat The Pointe Dance Center 2 Lollipop Murrieta Dance Project 3 Rotton To The Core The Pointe Dance Center Sapphire Petite Solo 1 Bop Kaitlyn Vandezande Arabesque Dance & Fitness Studio 2 Clap Snap Kymber Workman Inspire Dance Academy 3 Love Shack Diem Franch Inspire Dance Academy Sapphire Petite Duet/Trio 1 Let It Be Me Inspire Dance Academy 2 Big And Loud Inspire Dance Academy 3 Girls Gotta Inspire Dance Academy 4 Fabulous Feet Gymcats Sapphire Petite Small Group 1 Witch Doctor Dance Fusion 2 All I Do Is Work Gymcats 3 Jump Shout Boogie Dance Fusion Sapphire Pre-Junior Solo 1 Swagger Jagger Elena Gomez The Pointe Dance Center 2 Legends Are Made Tyler Workman Inspire Dance Academy 3 Zero To Hero Ziva Devargas Inspire Dance Academy 4 Stand Out Addison Lewis Gymcats 5 Perfect Isn't Easy Layla Lenz Gymcats 6 What's My Name Khloe Daniels The Pointe Dance Center 7 Immortals Jordan Tensay Inspire Dance Academy 8 Take On Me Giselle King Gymcats 9 Lovely Zhyion Saulsberry Studio 305, Home of the Rolle Project Showbiz Las Vegas 2021 Overalls Rank Routine Dancer Studio 10 Americano Paige Jarvis Inspire Dance Academy Sapphire Junior Solo 1 One Voice Jaycee Lareaux Dance Fusion 2 What You Want Harper Kristof Gymcats 3 Moon And Back Ava Hancock The Glow Dance 4 I'm A Lady Olivia Grant Inspire Dance Academy 5 -

Go the Distance Sheet Music Key of F.Pdf

From: “Walt Disney’s Hercules” Go the Distance from Walt Disney Pictures’ Hercules by ALAN MENKEN Lyrics by DAVID ZIPPEL Published Under License From Walt Disney Music Publishing © 1997 Wonderland Music Company, Inc. and Walt Disney Music Company All Rights Reserved Used by Permission Authorized for use by Caryssa Gilmore NOTICE: Purchasers of this musical file are entitled to use it for their personal enjoyment and musical fulfillment. However, any duplication, adaptation, arranging and/or transmission of this copyrighted music requires the written consent of the copyright owner(s) and of Musicnotes.com. Unauthorized uses are infringements of the copyright laws of the United States and other countries and may subject the user to civil and/or criminal penalties. Ǻ Musicnotes.com GO THE DISTANCE from Walt Disney Pictures’ HERCULES Music by ALAN MENKEN Slowly Lyrics by DAVID ZIPPEL F B C F x x x b x o o x x Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï b 4 Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï G 4 î Î «L.H. Ï Ï ú mf {} k F b 4 · î «. Ï 4 B C F Î Ï x b x o o x x Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï b Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï G ú. « L.H. Ï Ï ú {} . F b w ú Ï Ï w B C ú. -

2021 Breeze Show Choir Catalog

Previously Arranged Titles (updated 2/24/21) Specific details about each arrangement (including audio samples and cost) are available at https://breezetunes.com . The use of any of these arrangements requires a valid custom arrangement license purchased from https://tresonamusic.com . Their licensing fees typically range from $180 to $280 per song and must be paid before you can receive your music. Copyright approval frequently takes 4-6 weeks, sometimes longer, so plan accordingly. If changes to the arrangement are desired, there is an additional fee of $100. Examples of this include re-voicing (such as from SATB to another voice part), rewriting band parts, making cuts, adding an additional verse, etc. **Arrangements may be transposed into a different key free of charge, provided that the change does not make re-voicing necessary** For songs that do not have vocal rehearsal tracks, these can be created for $150/song. To place an order, send an e-mail to [email protected] or submit a license request on Tresona listing Garrett Breeze as the arranger, Tips for success using Previously Arranged Titles: • Most arrangements can be made to work in any voicing, so don’t be afraid to look at titles written for other combinations of voices than what you have. Most SATB songs, for example, can be easily reworked for SAT. • Remember that show function is one of the most important things to consider when purchasing an arrangement. For example, if something is labelled in the catalog as a Song 2/4, it is probably not going to work as a closer.