Download the Briefing (PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

Election Monitor No.49

Euro-Burma Office 10 November 22 November 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 49 DIPLOMATS OF FOREIGN MISSIONS OBSERVE VOTING PROCESS IN VARIOUS STATES AND REGIONS Representatives of foreign embassies and UN agencies based in Myanmar, members of the Myanmar Foreign Correspondents Club and local journalists observed the polling stations and studied the casting of votes at a number of polling stations on the day of the elections. According the state-run media, the diplomats and guests were organized into small groups and conducted to the various regions and states to witness the elections. The following are the number of polling stations and number of eligible voters for the various regions and states:1 1. Kachin State - 866 polling stations for 824,968 eligible voters. 2. Magway Region- 4436 polling stations in 1705 wards and villages with 2,695,546 eligible voters 3. Chin State - 510 polling stations with 66827 eligible voters 4. Sagaing Region - 3,307 polling stations with 3,114,222 eligible voters in 125 constituencies 5. Bago Region - 1251 polling stations and 1057656 voters 6. Shan State (North ) - 1268 polling stations in five districts, 19 townships and 839 wards/ villages and there were 1,060,807 eligible voters. 7. Shan State(East) - 506 polling stations and 331,448 eligible voters 8. Shan State (South)- 908,030 eligible voters cast votes at 975 polling stations 9. Mandalay Region - 653 polling stations where more than 85,500 eligible voters 10. Rakhine State - 2824 polling stations and over 1769000 eligible voters in 17 townships in Rakhine State, 1267 polling stations and over 863000 eligible voters in Sittway District and 139 polling stations and over 146000 eligible voters in Sittway Township. -

Restrictive Measures – Burma/Myanmar) (Jersey) Order 2008 Arrangement

Community Provisions (Restrictive Measures – Burma/Myanmar) (Jersey) Order 2008 Arrangement COMMUNITY PROVISIONS (RESTRICTIVE MEASURES – BURMA/MYANMAR) (JERSEY) ORDER 2008 Arrangement Article 1 Interpretation ................................................................................................... 3 2 Prohibitions on importation, etc., of goods originating in or exported from Burma/Myanmar .................................................................................... 4 3 Exceptions to prohibitions in Article 2 ........................................................... 5 4 Prohibition on exportation, etc., to Burma/Myanmar of goods which might be used for internal repression .............................................................. 5 5 Prohibition on exportation, etc., to Burma/Myanmar of goods for use in certain industries ......................................................................................... 5 6 Exception to Article 5 ..................................................................................... 6 7 Prohibition on provision of technical or financial assistance to persons in Burma/Myanmar ......................................................................................... 7 8 Prohibition on provision of technical assistance to enterprises in Burma/Myanmar engaged in certain industries .............................................. 7 9 Derogation for certain authorizations ............................................................. 8 10 Authorizations not to be retrospective ........................................................... -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 Amending Council Regulation

2008R0385 — EN — 30.04.2008 — 000.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 116, 30.4.2008, p. 5) Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0385 — EN — 30.04.2008 — 000.001 — 2 ▼B COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b), thereof, Whereas: (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enterprises owned or controlled by the Government of Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under that Regulation. (3) Common Position 2008/349/CFSP of 29 April 2008 (2) amends Annex II and Annex III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. -

REGLAMENTO DE EJECUCIÓN (UE) No 383/2011 DE LA COMISIÓN

L 103/8 ES Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea 19.4.2011 REGLAMENTO DE EJECUCIÓN (UE) N o 383/2011 DE LA COMISIÓN de 18 de abril de 2011 por el que se modifica el Reglamento (CE) n o 194/2008 del Consejo por el que se renuevan y se refuerzan las medidas restrictivas aplicables a Birmania/Myanmar (Texto pertinente a efectos del EEE) LA COMISIÓN EUROPEA, artículos 9, 10 y 13 de dicha Decisión y la lista de las empresas a las que se hace referencia en los artículos 10 Visto el Tratado de Funcionamiento de la Unión Europea, y 14 de dicha Decisión. El Reglamento (CE) n o 194/2008 confiere efecto a la Decisión 2010/232/PESC en la me Visto el Reglamento (CE) n o 194/2008 del Consejo, de 25 de dida en que es necesario actuar a nivel de la Unión. Por febrero de 2008, por el que se renuevan y refuerzan las medidas lo tanto, deberán modificarse en consecuencia los anexos restrictivas aplicables a Birmania/Myanmar y se deroga el Regla V, VI y VII del Reglamento (CE) n o 194/2008. o mento (CE) n 817/2006 ( 1), y, en particular, su artículo 18, apartado 1, letra b), (5) Por lo que se refiere a las personas físicas identificadas en el anexo IV de la Decisión 2011/239/PESC, los efectos de Considerando lo siguiente: su inclusión en la lista del anexo II de dicha Decisión quedan suspendidos. Procede incluir sus nombres en el o (1) El anexo V del Reglamento (CE) n 194/2008 establece la anexo VI del Reglamento (CE) n o 194/2008. -

A History of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964)

University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964) Kyaw Zaw Win University of Wollongong Win, Kyaw Zaw, A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964), PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 A HISTORY OF THE BURMA SOCIALIST PARTY (1930-1964) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong By Kyaw Zaw Win (BA (Q), BA (Hons), MA) School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts July 2008 Certification I, Kyaw Zaw Win, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Kyaw Zaw Win______________________ Kyaw Zaw Win 1 July 2008 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Glossary of Key Burmese Terms i-iii Acknowledgements iv-ix Abstract x Introduction xi-xxxiii Literature on the Subject Methodology Summary of Chapters Chapter One: The Emergence of the Burmese Nationalist Struggle (1900-1939) 01-35 1. Burmese Society under the Colonial System (1870-1939) 2. Patriotism, Nationalism and Socialism 3. Thakin Mya as National Leader 4. The Class Background of Burma’s Socialist Leadership 5. -

Commission Regulation (EC)

L 108/20 EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2009 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Common Position 2009/351/CFSP of 27 April 2009 ( 2 ) amends Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. Annexes VI and VII Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 should, therefore, be Community, amended accordingly. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 of (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regu- force immediately, lation (EC) No 817/2006 ( 1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b) thereof, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Whereas: Article 1 1. Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the replaced by the text of Annex I to this Regulation. persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. 2. Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby replaced by the text of Annex II to this Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enter- prises owned or controlled by the Government of Article 2 Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publi- that Regulation. -

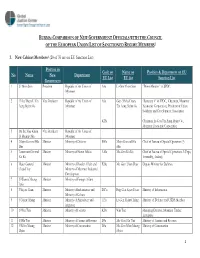

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 Renewing and Strengthening the Restrictive Measures in Respect of B

2008R0194 — EN — 16.05.2012 — 010.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 ►M5 Council Regulation (EU) No 408/2010 of 11 May 2010 L 118 5 12.5.2010 ►M6 Commission Regulation (EU) No 411/2010 of 10 May 2010 L 118 10 12.5.2010 ►M7 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 383/2011 of 18 April L 103 8 19.4.2011 2011 ►M8 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 891/2011 of 1 L 230 1 7.9.2011 September 2011 ►M9 Council Regulation (EU) No 1083/2011 of 27 October 2011 L 281 1 28.10.2011 ►M10 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1345/2011 of 19 December L 338 19 21.12.2011 2011 ►M11 Council Regulation (EU) No 409/2012 of 14 May 2012 L 126 1 15.5.2012 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. -

8016 12.Pdf 552,61 Kb

Vendredi 13 mai 2011 JOURNAL DE MONACO 867 Arrêtons : Information d’identification (fonction/titre, date et lieu ARTICLE PREMIER . # Nom (et alias éventuels) de naissance, numéro de sexe passeport/carte d’identité, (M/F) En application des dispositions prévues à l’article 2 de l’arrêté époux/épouse ou fils/fille de …) ministériel n° 2008-403, susvisé, l’annexe dudit arrêté est modifiée conformément à l’annexe du présent arrêté. Alf Aye Aye Thit Shwe Fille du Généralissime Than F Shwe ART . 2. Alg Tun Naing Shwe alias Tun Tun Fils du Généralissime Than M Naing Shwe. Propriétaire de J and J Le Conseiller de Gouvernement pour les Finances et l’Economie est company chargé de l’exécution du présent arrêté. Alh Khin Thanda Épouse de Tun Naing Shwe F Ali Kyaing San Shwe Fils du généralissime Than M Fait à Monaco, en l’Hôtel du Gouvernement, le vingt-neuf avril deux Shwe mille onze. Alj Dr. Khin Win Sein Épouse de Kyaing San Shwe F Alk Thant Zaw Shwe alias Fils du Généralissime Than M Le Ministre d’Etat, Maung Maung Shwe M. ROGER . All Dewar Shwe Fille du Généralissime Than F Shwe Alm Kyi Kyi Shwe alias Ma Aw Fille du Généralissime Than F Shwe ANNEXE DE L’ARRÊTÉ MINISTÉRIEL N°2011-251 Aln Lieutenant-colonel Mari de Kyi Kyi Shwe M DU 29 AVRIL 2011 MODIFIANT L’ARRÊTÉ MINISTÉRIEL Nay Soe Maung N° 2008-403 DU 30 JUILLET 2008 PORTANT APPLICATION DE L’ORDONNANCE SOUVERAINE N° 1.675 DU 10 JUIN 2008 Alo Pho La Pyae alias “full moon” et Fils de kyi Kyi Shwe et Nay M RELATIVE AUX PROCÉDURES DE GEL DES FONDS METTANT Nay Shwe Thway Aung Soe Maung, directeur de EN œUVRE DES SANCTIONS ÉCONOMIQUES. -

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 8 of the Export and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Import Law and S: 25 Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and of the Natural Disaster Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Management law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained.