Managing Technological Leaps : a Study of DEC's Alpha Design Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Perspective and Further Reading 162.E1

2.21 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 162.e1 2.21 Historical Perspective and Further Reading Th is section surveys the history of in struction set architectures over time, and we give a short history of programming languages and compilers. ISAs include accumulator architectures, general-purpose register architectures, stack architectures, and a brief history of ARMv7 and the x86. We also review the controversial subjects of high-level-language computer architectures and reduced instruction set computer architectures. Th e history of programming languages includes Fortran, Lisp, Algol, C, Cobol, Pascal, Simula, Smalltalk, C+ + , and Java, and the history of compilers includes the key milestones and the pioneers who achieved them. Accumulator Architectures Hardware was precious in the earliest stored-program computers. Consequently, computer pioneers could not aff ord the number of registers found in today’s architectures. In fact, these architectures had a single register for arithmetic instructions. Since all operations would accumulate in one register, it was called the accumulator , and this style of instruction set is given the same name. For example, accumulator Archaic EDSAC in 1949 had a single accumulator. term for register. On-line Th e three-operand format of RISC-V suggests that a single register is at least two use of it as a synonym for registers shy of our needs. Having the accumulator as both a source operand and “register” is a fairly reliable indication that the user the destination of the operation fi lls part of the shortfall, but it still leaves us one has been around quite a operand short. Th at fi nal operand is found in memory. -

Mi!!Lxlosalamos SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY

LA=8902-MS C3b ClC-l 4 REPORT COLLECTION REPRODUCTION COPY VAXNMS Benchmarking 1-’ > .— u) 9 g .— mi!!lxLOS ALAMOS SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY Post Office Box 1663 Los Alamos. New Mexico 87545 — wAifiimative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer b . l)lS(”L,\l\ll K “Thisreport wm prcpmd J, an xcttunt ,,1”wurk ,pmwrd by an dgmcy d the tlnitwl SIdtcs (kvcm. mm:. Ncit her t hc llniml SIJIL.. ( Lwcrnmcm nor any .gcncy tlhmd. nor my 08”Ihcif cmployccs. makci my wur,nly. mprcss w mphd. or JwImL.s m> lcg.d Iululity ur rcspmuhdily ltw Ilw w.cur- acy. .vmplctcncs. w uscftthtc>. ttt”any ml’ormdt ml. dpprdl us. prudu.i. w proccw didowd. or rep. resent%Ihd IIS us wuukl not mfrm$e priwtcly mvnd rqdtts. Itcl”crmcti herein 10 my sp.xi!l tom. mrcial ptotlucr. prtxcm. or S.rvskc hy tdc mmw. Irdcnmrl.. nmu(a.lurm. or dwrwi~.. does nut mmwsuily mnstitutc or reply its mdursmwnt. rccummcnddton. or favorin: by the llniwd States (“mvcmment ormy qxncy thctcd. rhc V!C$VSmd opinmm d .mthor% qmxd herein do nut net’. UMrily r;~lt or died lhow. ol”the llnttcd SIJIL.S( ;ovwnnwnt or my ugcncy lhure of. UNITED STATES .. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY CONTRACT W-7405 -ENG. 36 . ... LA-8902-MS UC-32 Issued: July 1981 G- . VAX/VMS Benchmarking Larry Creel —. I . .._- -- ----- ,. .- .-. .: .- ,.. .. ., ..,..: , .. .., . ... ..... - .-, ..:. .. *._–: - . VAX/VMS BENCHMARKING by Larry Creel ABSTRACT Primary emphasis in this report is on the perform- ance of three Digital Equipment Corporation VAX-11/780 computers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Programs used in the study are part of the Laboratory’s set of benchmark programs. -

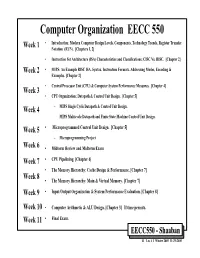

Computer Organization EECC 550 • Introduction: Modern Computer Design Levels, Components, Technology Trends, Register Transfer Week 1 Notation (RTN)

Computer Organization EECC 550 • Introduction: Modern Computer Design Levels, Components, Technology Trends, Register Transfer Week 1 Notation (RTN). [Chapters 1, 2] • Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Characteristics and Classifications: CISC Vs. RISC. [Chapter 2] Week 2 • MIPS: An Example RISC ISA. Syntax, Instruction Formats, Addressing Modes, Encoding & Examples. [Chapter 2] • Central Processor Unit (CPU) & Computer System Performance Measures. [Chapter 4] Week 3 • CPU Organization: Datapath & Control Unit Design. [Chapter 5] Week 4 – MIPS Single Cycle Datapath & Control Unit Design. – MIPS Multicycle Datapath and Finite State Machine Control Unit Design. Week 5 • Microprogrammed Control Unit Design. [Chapter 5] – Microprogramming Project Week 6 • Midterm Review and Midterm Exam Week 7 • CPU Pipelining. [Chapter 6] • The Memory Hierarchy: Cache Design & Performance. [Chapter 7] Week 8 • The Memory Hierarchy: Main & Virtual Memory. [Chapter 7] Week 9 • Input/Output Organization & System Performance Evaluation. [Chapter 8] Week 10 • Computer Arithmetic & ALU Design. [Chapter 3] If time permits. Week 11 • Final Exam. EECC550 - Shaaban #1 Lec # 1 Winter 2005 11-29-2005 Computing System History/Trends + Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Fundamentals • Computing Element Choices: – Computing Element Programmability – Spatial vs. Temporal Computing – Main Processor Types/Applications • General Purpose Processor Generations • The Von Neumann Computer Model • CPU Organization (Design) • Recent Trends in Computer Design/performance • Hierarchy -

Phaser 600 Color Printer User Manual

WELCOME! This is the home page of the Phaser 600 Color Printer User Manual. See Tips on using this guide, or go immediately to the Contents. Phaser® 600 Wide-Format Color Printer Tips on using this guide ■ Use the navigation buttons in Acrobat Reader to move through the document: 1 23 4 5 6 1 and 4 are the First Page and Last Page buttons. These buttons move to the first or last page of a document. 2 and 3 are the Previous Page and Next Page buttons. These buttons move the document backward or forward one page at a time. 5 and 6 are the Go Back and Go Forward buttons. These buttons let you retrace your steps through a document, moving to each page or view in the order visited. ■ For best results, use the Adobe Acrobat Reader version 2.1 to read this guide. Version 2.1 of the Acrobat Reader is supplied on your printer’s CD-ROM. ■ Click on the page numbers in the Contents on the following pages to open the topics you want to read. ■ You can click on the page numbers following keywords in the Index to open topics of interest. ■ You can also use the Bookmarks provided by the Acrobat Reader to navigate through this guide. If the Bookmarks are not already displayed at the left of the window, select Bookmarks and Page from the View menu. ■ If you have difficultly reading any small type or seeing the details in any of the illustrations, you can use the Acrobat Reader’s Magnification feature. -

RISC-V Geneology

RISC-V Geneology Tony Chen David A. Patterson Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2016-6 http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2016/EECS-2016-6.html January 24, 2016 Copyright © 2016, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission. Introduction RISC-V is an open instruction set designed along RISC principles developed originally at UC Berkeley1 and is now set to become an open industry standard under the governance of the RISC-V Foundation (www.riscv.org). Since the instruction set architecture (ISA) is unrestricted, organizations can share implementations as well as open source compilers and operating systems. Designed for use in custom systems on a chip, RISC-V consists of a base set of instructions called RV32I along with optional extensions for multiply and divide (RV32M), atomic operations (RV32A), single-precision floating point (RV32F), and double-precision floating point (RV32D). The base and these four extensions are collectively called RV32G. This report discusses the historical precedents of RV32G. We look at 18 prior instruction set architectures, chosen primarily from earlier UC Berkeley RISC architectures and major proprietary RISC instruction sets. Among the 122 instructions in RV32G: ● 6 instructions do not have precedents among the selected instruction sets, ● 98 instructions of the 116 with precedents appear in at least three different instruction sets. -

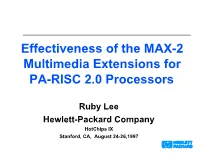

Effectiveness of the MAX-2 Multimedia Extensions for PA-RISC 2.0 Processors

Effectiveness of the MAX-2 Multimedia Extensions for PA-RISC 2.0 Processors Ruby Lee Hewlett-Packard Company HotChips IX Stanford, CA, August 24-26,1997 Outline Introduction PA-RISC MAX-2 features and examples Mix Permute Multiply with Shift&Add Conditionals with Saturation Arith (e.g., Absolute Values) Performance Comparison with / without MAX-2 General-Purpose Workloads will include Increasing Amounts of Media Processing MM a b a b 2 1 2 1 b c b c functionality 5 2 5 2 A B C D 1 2 22 2 2 33 3 4 55 59 A B C D 1 2 A B C D 22 1 2 22 2 2 2 2 33 33 3 4 55 59 3 4 55 59 Distributed Multimedia Real-time Information Access Communications Tool Tool Computation Tool time 1980 1990 2000 Multimedia Extensions for General-Purpose Processors MAX-1 for HP PA-RISC (product Jan '94) VIS for Sun Sparc (H2 '95) MAX-2 for HP PA-RISC (product Mar '96) MMX for Intel x86 (chips Jan '97) MDMX for SGI MIPS-V (tbd) MVI for DEC Alpha (tbd) Ideally, different media streams map onto both the integer and floating-point datapaths of microprocessors images GR: GR: 32x32 video 32x64 ALU SMU FP: graphics FP:16x64 Mem 32x64 audio FMAC PA-RISC 2.0 Processor Datapath Subword Parallelism in a General-Purpose Processor with Multimedia Extensions General Regs. y5 y6 y7 y8 x5 x6 x7 x8 x1 x2 x3 x4 y1 y2 y3 y4 Partitionable Partitionable 64-bit ALU 64-bit ALU 8 ops / cycle Subword Parallel MAX-2 Instructions in PA-RISC 2.0 Parallel Add (modulo or saturation) Parallel Subtract (modulo or saturation) Parallel Shift Right (1,2 or 3 bits) and Add Parallel Shift Left (1,2 or 3 bits) and Add Parallel Average Parallel Shift Right (n bits) Parallel Shift Left (n bits) Mix Permute MAX-2 Leverages Existing Processing Resources FP: INTEGER FLOAT GR: 16x64 General Regs. -

Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture

Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture Andrew Waterman Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2016-1 http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2016/EECS-2016-1.html January 3, 2016 Copyright © 2016, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission. Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture by Andrew Shell Waterman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David Patterson, Chair Professor Krste Asanovi´c Associate Professor Per-Olof Persson Spring 2016 Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture Copyright 2016 by Andrew Shell Waterman 1 Abstract Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture by Andrew Shell Waterman Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science University of California, Berkeley Professor David Patterson, Chair The hardware-software interface, embodied in the instruction set architecture (ISA), is arguably the most important interface in a computer system. Yet, in contrast to nearly all other interfaces in a modern computer system, all commercially popular ISAs are proprietary. -

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 L/780

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 l/780 Joel S. Emer Douglas W. Clark Digital Equipment Corp. Digital Equipment Corp. 77 Reed Road 295 Foster Street Hudson, MA 01749 Littleton, MA 01460 ABSTRACT effect of many architectural and implementation features. This paper reports the results of a study of VAX- llR80 processor performance using a novel hardware Prior related work includes studies of opcode monitoring technique. A micro-PC histogram frequency and other features of instruction- monitor was buiit for these measurements. It kee s a processing [lo. 11,15,161; some studies report timing count of the number of microcode cycles execute z( at Information as well [l, 4,121. each microcode location. Measurement ex eriments were performed on live timesharing wor i loads as After describing our methods and workloads in well as on synthetic workloads of several types. The Section 2, we will re ort the frequencies of various histogram counts allow the calculation of the processor events in 5 ections 3 and 4. Section 5 frequency of various architectural events, such as the resents the complete, detailed timing results, and frequency of different types of opcodes and operand !!Iection 6 concludes the paper. specifiers, as well as the frequency of some im lementation-s ecific events, such as translation bu h er misses. ?phe measurement technique also yields the amount of processing time spent, in various 2. DEFINITIONS AND METHODS activities, such as ordinary microcode computation, memory management, and processor stalls of 2.1 VAX-l l/780 Structure different kinds. This paper reports in detail the amount of time the “average’ VAX instruction The llf780 processor is composed of two major spends in these activities. -

Computer Architectures an Overview

Computer Architectures An Overview PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 25 Feb 2012 22:35:32 UTC Contents Articles Microarchitecture 1 x86 7 PowerPC 23 IBM POWER 33 MIPS architecture 39 SPARC 57 ARM architecture 65 DEC Alpha 80 AlphaStation 92 AlphaServer 95 Very long instruction word 103 Instruction-level parallelism 107 Explicitly parallel instruction computing 108 References Article Sources and Contributors 111 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 113 Article Licenses License 114 Microarchitecture 1 Microarchitecture In computer engineering, microarchitecture (sometimes abbreviated to µarch or uarch), also called computer organization, is the way a given instruction set architecture (ISA) is implemented on a processor. A given ISA may be implemented with different microarchitectures.[1] Implementations might vary due to different goals of a given design or due to shifts in technology.[2] Computer architecture is the combination of microarchitecture and instruction set design. Relation to instruction set architecture The ISA is roughly the same as the programming model of a processor as seen by an assembly language programmer or compiler writer. The ISA includes the execution model, processor registers, address and data formats among other things. The Intel Core microarchitecture microarchitecture includes the constituent parts of the processor and how these interconnect and interoperate to implement the ISA. The microarchitecture of a machine is usually represented as (more or less detailed) diagrams that describe the interconnections of the various microarchitectural elements of the machine, which may be everything from single gates and registers, to complete arithmetic logic units (ALU)s and even larger elements. -

The Implementation of Prolog Via VAX 8600 Microcode ABSTRACT

The Implementation of Prolog via VAX 8600 Microcode Jeff Gee,Stephen W. Melvin, Yale N. Patt Computer Science Division University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 ABSTRACT VAX 8600 is a 32 bit computer designed with ECL macrocell arrays. Figure 1 shows a simplified block diagram of the 8600. We have implemented a high performance Prolog engine by The cycle time of the 8600 is 80 nanoseconds. directly executing in microcode the constructs of Warren’s Abstract Machine. The imulemention vehicle is the VAX 8600 computer. The VAX 8600 is a general purpose processor Vimal Address containing 8K words of writable control store. In our system, I each of the Warren Abstract Machine instructions is implemented as a VAX 8600 machine level instruction. Other Prolog built-ins are either implemented directly in microcode or executed by the general VAX instruction set. Initial results indicate that. our system is the fastest implementation of Prolog on a commercrally available general purpose processor. 1. Introduction Various models of execution have been investigated to attain the high performance execution of Prolog programs. Usually, Figure 1. Simplified Block Diagram of the VAX 8600 this involves compiling the Prolog program first into an intermediate form referred to as the Warren Abstract Machine (WAM) instruction set [l]. Execution of WAM instructions often follow one of two methods: they are executed directly by a The 8600 consists of six subprocessors: the EBOX. IBOX, special purpose processor, or they are software emulated via the FBOX. MBOX, Console. and UO adamer. Each of the seuarate machine language of a general purpose computer. -

VAX VMS at 20

1977–1997... and beyond Nothing Stops It! Of all the winning attributes of the OpenVMS operating system, perhaps its key success factor is its evolutionary spirit. Some would say OpenVMS was revolutionary. But I would prefer to call it evolutionary because its transition has been peaceful and constructive. Over a 20-year period, OpenVMS has experienced evolution in five arenas. First, it evolved from a system running on some 20 printed circuit boards to a single chip. Second, it evolved from being proprietary to open. Third, it evolved from running on CISC-based VAX to RISC-based Alpha systems. Fourth, VMS evolved from being primarily a technical oper- ating system, to a commercial operat- ing system, to a high availability mission-critical commercial operating system. And fifth, VMS evolved from time-sharing to a workstation environment, to a client/server computing style environment. The hardware has experienced a similar evolution. Just as the 16-bit PDP systems laid the groundwork for the VAX platform, VAX laid the groundwork for Alpha—the industry’s leading 64-bit systems. While the platforms have grown and changed, the success continues. Today, OpenVMS is the most flexible and adaptable operating system on the planet. What start- ed out as the concept of ‘Starlet’ in 1975 is moving into ‘Galaxy’ for the 21st century. And like the universe, there is no end in sight. —Jesse Lipcon Vice President of UNIX and OpenVMS Systems Business Unit TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I Changing the Face of Computing 4 CHAPTER II Setting the Stage 6 CHAPTER -

Vincent M. Weaver Sally A. Mckee

Optimizing for Size: Exploring the Limits of Code Density Sally A. McKee Vincent M. Weaver ASPLOS XIV Poster Session, 8 March 2009 Cornell University Chalmers University of Technology Abstract Hand-Optimized Assembly Results Architectural Size Correlations 0.9020 Minimum possible instruction size Reductions in instruction count can improve cache and bandwidth utiliza- 0.8652 Number of integer registers tion, lower power consumption, and increase overall performance. Nonethe- Total Size of Executable VLIW 2560 RISC less, code density is often overlooked when studying processor architectures. 2048 CISC 0.6623 Architecture has a zero register embedded 1536 8/16-bit 0.5845 Bit-width bytes 1024 We hand-optimize an embedded benchmark for size in assembly language -0.4366 Hardware divide in ALU on 20 different instruction set architectures and investigate the architectural 512 features that contribute most heavily to code density. 0 0.4385 Number of operands in each instruction arm ppc vax sh3 z80 ia64 6502 mips s390 i386 alphaparisc sparc m88k m68k thumb avr32 -0.3356 Unaligned load/store available x86_64 crisv32pdp-11 0.2773 Year the architecture was introduced 256 Size of LZSS Decompression Code VLIW -0.2597 Auto-incrementing addressing scheme Background RISC CISC 192 embedded -0.2597 Hardware status flags (zero/overflow/etc.) 128 8/16-bit bytes -0.1252 Little or Big endian 64 The 20 architectures investigated can be broadly broken into 5 categories: -0.0487 Branch delay slot 0 -0.0079 Maximum possible instruction size Instr Length Opcode arm ppc vax z80 sh3 ia64 mips s390 6502 i386 Type Represented Architectures alpha parisc sparc m88k m68kthumb avr32 (bytes) Args pdp-11 x86_64crisv32 VLIW ia64 16/3 3 Size of String-Search Code VLIW Other Considerations alpha, arm, m88k, mips 256 RISC RISC 4 3 CISC pa-risc, ppc, sparc 192 embedded 128 8/16-bit System libraries and compiler overhead can overshadow the effects of size bytes CISC m68k, s390, vax, x86, x86 64 1-54 2 64 optimization, increasing memory footprint by several orders of magnitude.