Aspirational Paratexts: the Case of “Quality Openers” in TV Promotion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Strategy: the Blind Spot of International Humanitarian Law

Harvard National Security Journal / Vol. 8 333 ARTICLE Military Strategy: The Blind Spot of International Humanitarian Law Yishai Beer* * Professor of Law, Herzliya Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya, Israel. The author would like to thank Eyal Benvenisti, Gabriella Blum, Moshe Halbertal, Eliav Lieblich, David Kretzmer, and Kenneth Watkin for their useful comments, and Ohad Abrahami for his research assistance. © 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College and Yishai Beer. 334 2017 / Military Strategy: The Blind Spot of International Humanitarian Law Abstract The stated agenda of international humanitarian law (IHL) is to humanize war’s arena. Since it is the strategic level of war that primarily affects war’s conduct, one might have expected that the law would focus upon it. Paradoxically, the current law generally ignores the strategic discourse and prefers to scrutinize the conduct of war through a tactical lens. This disregard of military strategy has a price that is demonstrated in the prevailing law of targeting. This Article challenges the current blind spot of IHL: its disregard of the direct consequences of war strategy and the war aims deriving from it. It asks those who want to comprehensively reduce war’s hazards to think strategically and to leverage military strategy as a constraining tool. The effect of the suggested approach is demonstrated through an analysis of targeting rules, where the restrictive attributes of military strategy, which could play a significant role in limiting targeting, have been overlooked. Harvard National Security Journal / Vol. 8 335 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................336 I. Strategy Determines War’s Patterns and Scope .........................................340 II. -

National Strategy for Homeland Security 2007

national strategy for HOMELAND SECURITY H OMELAND SECURITY COUNCIL OCTOBER 2 0 0 7 national strategy for HOMELAND SECURITY H OMELAND SECURITY COUNCIL OCTOBER 2 0 0 7 My fellow Americans, More than 6 years after the attacks of September 11, 2001, we remain at war with adversar- ies who are committed to destroying our people, our freedom, and our way of life. In the midst of this conflict, our Nation also has endured one of the worst natural disasters in our history, Hurricane Katrina. As we face the dual challenges of preventing terrorist attacks in the Homeland and strengthening our Nation’s preparedness for both natural and man-made disasters, our most solemn duty is to protect the American people. The National Strategy for Homeland Security serves as our guide to leverage America’s talents and resources to meet this obligation. Despite grave challenges, we also have seen great accomplishments. Working with our part- ners and allies, we have broken up terrorist cells, disrupted attacks, and saved American lives. Although our enemies have not been idle, they have not succeeded in launching another attack on our soil in over 6 years due to the bravery and diligence of many. Just as our vision of homeland security has evolved as we have made progress in the War on Terror, we also have learned from the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina. We witnessed countless acts of courage and kindness in the aftermath of that storm, but I, like most Americans, was not satisfied with the Federal response. We have applied the lessons of Katrina to thisStrategy to make sure that America is safer, stronger, and better prepared. -

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

Sean Callery

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD Jessica Jones Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2016) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Minority Report Outstanding Music Composition For A Series, Original Dramatic Score (2016) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD TV Composer of the Year (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Homeland Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2012) ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION Homeland ASSOCIATION Best Music in a Series (2002) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2011) GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006, 2003) The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Outstanding Individual Achievement in Sound Editing for a Series (1993) *shared TELEVISION SERIES DOUBT (series) Tony Phelan, Joan Rater, Sarah Timberman, Carl CBS Beverly, Adam Bernstein, exec prods. 24: LEGACY (pilot & series) Kiefer Sutherland, Stephen Hopkins, Howard Gordon, 20 TH Century Fox Brian Grazer, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, exec. prods. Evan Katz, Manny Coto, showrunners DESIGNATED SURVIVOR (pilot & David Guggenheim, Kiefer Sutherland, Mark series) Gordon, Simon Kinberg, Suzan Bymel, Aditya ABC / Mark Gordon Company Sood, Amy Harris, exec. -

9110-9P Department of Homeland Security

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 06/23/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-13109, and on govinfo.gov 9110-9P DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY [Docket No. CISA-2020-0018] Agency Information Collection Activities: Proposed Collection; Comment Request; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Visitor Request Form AGENCY: Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Department of Homeland Security (DHS). ACTION: 30-day notice and request for comments; reinstatement without change of information collection request: 1670-0036. SUMMARY: The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Office of Compliance and Security (OCS), as part of its continuing effort to reduce paperwork and respondent burden, invites the general public to take this opportunity to comment on a reinstatement, without change, of a previously approved information collection for which approval has expired. CISA will submit the following Information Collection Request to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review and clearance in accordance with the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995. CISA previously published a notice about this ICR, in the Federal Register on February 17, 2021, for a 60-day public comment period. There were no comments received. The purpose of this notice is to allow additional 30-days for public comments. DATES: The comment period for the information collection request published on February 17, 2021 at 86 FR 9949. Comments must be submitted on or before [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: Written comments and recommendations for the proposed information collection should be sent within 30 days of publication of this notice to www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAMain . -

Pointing Towards Clarity Or Missing the Point? a Critique of the Proposed "Social Group" Rule and Its Impact on Gender-Based Political Asylum

POINTING TOWARDS CLARITY OR MISSING THE POINT? A CRITIQUE OF THE PROPOSED "SOCIAL GROUP" RULE AND ITS IMPACT ON GENDER-BASED POLITICAL ASYLUM LOREN G. STEWART* From the beginning of the marriage, her husband abused her. He raped her almost daily, beating her before and during each rape. He once dislocated her jawbone because her menstrual period was fifteen days late. When she refused to abort a pregnancy, he kicked her violently in her spine. Once, he kicked her in her genitalia, causing her severe pain and eight days of bleeding. She fled the city with their children, but he tracked them down and beat her unconscious. He broke windows and mirrors with her head. He told her that if she left him, he would find her, cut off her arms and legs with a machete and leave her in a wheelchair. She attempted suicide, but was unsuccessful. She contacted the police three times, but they did not respond. A judge denied her protection, saying that the court "would not interfere in domestic disputes."' She finally left him, fled to the United States, and applied for political asylum. Should women like Rodi Alvarado Pefia, described above, be eligible to receive political asylum in the United States?2 To be J.D. Candidate 2005, University of Pennsylvania Law School. B.A. History, cum laude, Yale University 1999. The author wishes to express his gratitude to Professors Fernando Chang-Muy, Louis S. Rulli and Catherine Struve for their guidance, enthusiasm, and inspiration. ratience,In re R-A-, 22 I. & N. Dec. 906, 908-10 (BIA 1999, Att'y Gen. -

A Film by Kim A. Snyder Produced by Maria Cuomo

PRESENTS *OFFICIAL SELECTION – 2016 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL* *OFFICIAL SELECTION – 2016 SXSW FILM FESTIVAL* A FILM BY KIM A. SNYDER PRODUCED BY MARIA CUOMO COLE OPENS IN THEATERS OCTOBER 7 2016 // USA // 85 Minutes NY Press Contacts Abramorama Contacts LA Press Contact Ryan Werner Richard Abramowitz Nancy Willen 917-254-7653 914-741-1818 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Charlie Olsky Liv Abramowitz 917-545-7260 914-741-1818 [email protected] [email protected] www.NewtownFilm.com #WeAreAllNewtown SYNOPSIS A proud Labor Day parade floats by as hundreds of parents and children line the streets in the last gasps of summer. It is made up of local leadership, a brigade of first responders, the town priest, a high school marching band and a magic school bus in a town that could be Anytown, America. Yet this isn’t any town. It’s Newtown. Twenty months after the horrific mass shooting in Newtown, CT that took the lives of twenty elementary school children and six educators on December 14, 2012, the small New England town is a complex psychological web of tragic aftermath in the wake of yet another act of mass killing at the hands of a disturbed young gunman. Kim A. Snyder’s searing Newtown documents a traumatized community fractured by grief and driven toward a sense of purpose. There are no easy answers, no words of compassion or reassurance that can bring back those who lost their lives during the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Instead, Snyder gives us exclusive access into the lives and homes of those who remain, all of whom have been indelibly changed by the events. -

Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary

Blind Spot: Hitler’s Secretary Dir: Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, Austria, 2003 A review by Jessica Lang, John Hopkins University, USA Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary, a documentary film directed by Andre Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, is the first published account of Traudl Humps Junge's memories as Hitler's secretary from 1942 until his suicide in 1945. The ninety minute film, which came out in 2002, was edited from more than ten hours of footage. The result is a disturbing compilation of memories and reflections on those memories that, while interesting enough, are presented in a way that is at best uneven. Part of this unevenness is a product of the film's distribution of time: while it begins with Junge's recalling how she interviewed for her secretarial position in order to quit another less enjoyable job, most of it is spent reflecting on Hitler as his regime and military conquests collapsed around him. But the film also is not balanced in terms of its reflectivity, abandoning halfway through some of its most interesting and most important narrative strategies. In terms of its construction, the film involves Junge speaking directly to the camera. She speaks with little prompting (that the audience can hear, at least) and appears to have retained a footprint of war memories that has remained almost perfectly intact through the sixty years she has kept them largely to herself. Interrupted by sudden editing breaks, the viewer is rushed through the first two and a half years of Junge's employment in the first half of the film. -

A Governor's Guide to Homeland Security

A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION (NGA), founded in 1908, is the instrument through which the nation’s governors collectively influence the development and implementation of national policy and apply creative leadership to state issues. Its members are the governors of the 50 states, three territories and two commonwealths. The NGA Center for Best Practices is the nation’s only dedicated consulting firm for governors and their key policy staff. The NGA Center’s mission is to develop and implement innovative solutions to public policy challenges. Through the staff of the NGA Center, governors and their policy advisors can: • Quickly learn about what works, what doesn’t and what lessons can be learned from other governors grappling with the same problems; • Obtain specialized assistance in designing and implementing new programs or improving the effectiveness of current programs; • Receive up-to-date, comprehensive information about what is happening in other state capitals and in Washington, D.C., so governors are aware of cutting-edge policies; and • Learn about emerging national trends and their implications for states, so governors can prepare to meet future demands. For more information about NGA and the Center for Best Practices, please visit www.nga.org. A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY NGA Center for Best Practices Homeland Security & Public Safety Division FEBRUARY 2019 Acknowledgements A Governor’s Guide to Homeland Security was produced by the Homeland Security & Public Safety Division of the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) including Maggie Brunner, Reza Zomorrodian, David Forscey, Michael Garcia, Mary Catherine Ott, and Jeff McLeod. -

Click to Download

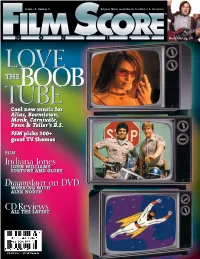

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

Transnational Ethnic Communities and Rebel Groups' Strategies in a Civil Conflict

Transnational Ethnic Communities and Rebel Groups’ Strategies in a Civil Conflict The case of the Karen National Union rebellion in Myanmar Bethsabée Souris University College London (UCL) 2020 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science I, Bethsabée Souris, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis 1 2 Abstract Few studies have systematically analysed how transnational ethnic kin groups affect the behaviour of domestic ethnic groups in an insurgency, in particular how they have an effect on the types of activities they conduct and their targets. The research question of this study is: What are the mechanisms through which transnational ethnic kin groups influence the domestic rebel ethnic group’s strategies? This thesis analyses the influence of transnational communities on domestic challengers to the state as a two-step process. First, it investigates under which conditions transnational ethnic kin groups provide political and economic support to the rebel ethnic group. It shows that networks between rebel groups and transnational communities, which can enable the diffusion of the rebel group’s conflict frames, are key to ensure transnational support. Second, it examines how such transnational support can influence rebel groups’ strategies. It shows that central to our understanding of rebel groups’ strategies is the cohesion (or lack thereof) of the rebel group. Furthermore, it identifies two sources of rebel group’s fragmentation: the state counter-insurgency strategies, and transnational support. The interaction of these two factors can contribute to the fragmentation of the group and in turn to a shift in the strategies it conducts. -

Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland

This is a repository copy of “Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150191/ Version: Published Version Article: Steenberg, L and Tasker, Y (2015) “Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland. Cinema Journal, 54 (4). pp. 132-138. ISSN 0009-7101 https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2015.0042 This article is protected by copyright. Reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cinema Journal 54 i No. 4 I Summer 2015 "Pledge Allegiance": Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and H o m e la n d by Lindsay Steenber g and Yvonne Tasker lthough there are numerous intertexts for the series, here we situate Homeland (Showtime, 2011—) in the generic context of American crime television. Homeland draws on and develops two of this genre’s most highly visible tropes: constant vigilance regardingA national borders (for which the phrase “homeland security” comes to serve as cultural shorthand) and the vital yet precariously placed female investigator.