A Film by Kim A. Snyder Produced by Maria Cuomo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON Is More Than a Running Film. It Is a Timeless Story About Triumph Over Adversity for Runner and Non-Runner Alike. Film Sy

BOSTON is more than a running film. It is a timeless story about triumph over adversity for runner and non-runner alike. Film Synopsis BOSTON is the first ever feature-length documentary film about the world’s most legendary run- ning race – the Boston Marathon. The film chronicles the story of the iconic race from its humble origins with only 15 runners to the present day. In addition to highlighting the event as the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the film showcases many of the most important moments in more than a century of the race’s history. from a working man’s challenge welcoming foreign athletes and eventually women bec me the stage for manyThe Bostonfirsts and Marathon in no small evolved part the event that paved the way for the modern into a m world-classarathon and event, mass participatory sports. Following the tragic events of. The 2013, Boston BOSTON Marathon a the preparations and eventual running of the, 118th Boston Marathon one year later when runners and community gather once again for what will be the most meaningful raceshowcases of all. for , together The production was granted exclusive documentary rights from the Boston Athletic Association to produce the film and to use the Association’s extensive archive of video, photos and memorabilia. Production Credits: Boston is presented by John Hancock Financial, in association with the Kennedy/Marshall Com- pany. The film is directed by award winning filmmaker Jon Dunham, well known for his Spirit of the Marathon films, and produced by Academy Award-nominee Megan Williams and Eleanor Bingham Miller. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Sean Callery

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD Jessica Jones Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2016) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Minority Report Outstanding Music Composition For A Series, Original Dramatic Score (2016) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD TV Composer of the Year (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Homeland Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2012) ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION Homeland ASSOCIATION Best Music in a Series (2002) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2011) GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006, 2003) The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Outstanding Individual Achievement in Sound Editing for a Series (1993) *shared TELEVISION SERIES DOUBT (series) Tony Phelan, Joan Rater, Sarah Timberman, Carl CBS Beverly, Adam Bernstein, exec prods. 24: LEGACY (pilot & series) Kiefer Sutherland, Stephen Hopkins, Howard Gordon, 20 TH Century Fox Brian Grazer, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, exec. prods. Evan Katz, Manny Coto, showrunners DESIGNATED SURVIVOR (pilot & David Guggenheim, Kiefer Sutherland, Mark series) Gordon, Simon Kinberg, Suzan Bymel, Aditya ABC / Mark Gordon Company Sood, Amy Harris, exec. -

Racing Extinction

Racing Extinction Directed by Academy Award® winner Louie Psihoyos And the team behind THE COVE RACING EXTINCTION will have a worldwide broadcast premiere on The Discovery Channel December 2nd. Publicity Materials Are Available at: www.racingextinction.com Running Time: 94 minutes Press Contacts: Discovery Channel: Sunshine Sachs Jackie Lamaj NY/LA/National Office: 212.548.5607 Office: 212.691.2800 Email: [email protected] Tiffany Malloy Email: [email protected] Jacque Seaman Vulcan Productions: Email: [email protected] Julia Pacetti Office: 718.399.0400 Email: [email protected] 1 RACING EXTINCTION Synopsis Short Synopsis Oscar®-winning director Louie Psihoyos (THE COVE) assembles a team of artists and activists on an undercover operation to expose the hidden world of endangered species and the race to protect them against mass extinction. Spanning the globe to infiltrate the world’s most dangerous black markets and using high tech tactics to document the link between carbon emissions and species extinction, RACING EXTINCTION reveals stunning, never-before seen images that truly change the way we see the world. Long Synopsis Scientists predict that humanity’s footprint on the planet may cause the loss of 50% of all species by the end of the century. They believe we have entered the sixth major extinction in Earth’s history, following the fifth great extinction which took out the dinosaurs. Our era is called the Anthropocene, or “Age of Man,” because evidence shows that humanity has sparked a cataclysmic change of the world’s natural environment and animal life. Yet, we are the only ones who can stop the change we have created. -

Click to Download

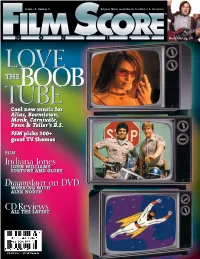

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

DAVID NORLAND Composer TELEVISION CREDITS

DAVID NORLAND Composer David Norland is an English composer living and working in Los Angeles. Most recently he composed the score to the current HBO film My Dinner With Herve (HBO 2018) starring Peter Dinklage and Jamie Dornan. His work with Emmy-winning director Sacha Gervasi includes the award-winning documentary Anvil! The Story Of Anvil. Anvil! won the IDA Best Feature award, an Emmy award, the Indie Spirit Best Documentary award, and numerous other Best Documentary awards around the world. His most recent collaboration with Sacha was on November Criminals (Sony 2017) starring Chloe Moretz and Ansel Elgort. Since 2010, David has composed much of the music for USA broadcasting giant ABC’s primetime news documentaries. His work for ABC is broadcast in the USA and around the world on a daily basis. A chorister from an early age, David was singing daily in Westminster Abbey, was a boy treble in The Elizabethan Consort of Voices and sang in a reputable touring choral group during the time. Having a love for choral music, David also finds time to write for choir. In addition to composition & choral music, David was a successful recording artist and record producer. His electronic band Solar Twins was signed by Madonna to Maverick Records and rode high on the USA dance charts, and his record writing, production and mixing work with Jamaican legends Sly and Robbie has been nominated for a Grammy. TELEVISION CREDITS My Dinner with Hervé (TV Movie) Good Morning America (TV Series) (additional Director: Sacha Gervasi music) Daredevil Films -

Screen Romantic Genius.Pdf MUSIC AND

“WHAT ONE MAN CAN INVENT, ANOTHER CAN DISCOVER” MUSIC AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF SHERLOCK HOLMES FROM LITERARY GENTLEMAN DETECTIVE TO ON-SCREEN ROMANTIC GENIUS By Emily Michelle Baumgart A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Musicology – Master of Arts 2015 ABSTRACT “WHAT ONE MAN CAN INVENT, ANOTHER CAN DISCOVER” MUSIC AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF SHERLOCK HOLMES FROM LITERARY GENTLEMAN DETECTIVE TO ON-SCREEN ROMANTIC GENIUS By Emily Michelle Baumgart Arguably one of the most famous literary characters of all time, Sherlock Holmes has appeared in numerous forms of media since his inception in 1887. With the recent growth of on-screen adaptations in both film and serial television forms, there is much new material to be analyzed and discussed. However, recent adaptations have begun exploring new reimaginings of Holmes, discarding his beginnings as the Victorian Gentleman Detective to create a much more flawed and multi-faceted character. Using Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original work as a reference point, this study explores how recent adaptors use both Holmes’s diegetic violin performance and extra-diegetic music. Not only does music in these screen adaptations take the role of narrative agent, it moreover serves to place the character of Holmes into the Romantic Genius archetype. Copyright by EMILY MICHELLE BAUMGART 2015 .ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am incredibly grateful to my advisor Dr. Kevin Bartig for his expertise, guidance, patience and good humor while helping me complete this document. Thank you also to my committee members Dr. Joanna Bosse and Dr. Michael Largey for their new perspectives and ideas. -

August 2015: Organize! Together We

AFM LOCAL 47 Vol. 1 No. 8 August 2015 ORGANIZE! TOGETHER WE WIN THE TRUTH ABOUT FI-CORE Let’s Get Organized! Facing fi-core coercion? Learn what you Meet our new organizer, and your union can do about it Merideth Cleary DISCLAIMER Overture Online is optimized for viewing in its native App version as published in the Apple App Store & Google Play. This pdf version of Overture Online does not contain the live html links or other interactive elements as they appear in the App version, and serves to exist for archival reference only. A digital archive of Overture Online containing all interactive elements may be accessed at the following link: afm47.org/press/category/overture-online ISSN: 2379-1322 Publisher Editor AFM Local 47 Gary Lasley 817 Vine Street Managing Editor / Ad Manager Hollywood, CA 90038-3779 Linda A. Rapka p 323.462.2161 f 323.461.3090 Graphic Design / Layout Assistant www.afm47.org Candace Evans Titled Officers Hearing Board President: John Acosta Alan Estes, Chuck Flores, Overture Online is the official electronic Vice President: Rick Baptist Jon Kurnick, Jeff Lass, monthly magazine of the American Federa- Secretary/Treasurer: Gary Lasley Norman Ludwin, Allen Savedoff, tion of Musicians Local 47, a labor union for Marc Sazer Trustees professional musicians located in Holly- Judy Chilnick, Dylan Hart, Hearing Representative wood. Bonnie Janofsky Vivian Wolf Directors Salary Review Board Formed by and for Los Angeles musicians Pam Gates, John Lofton, Rick Baptist, Stephen Green, Andy Malloy, Phil O’Connor, Norman Ludwin, Marie Matson, Paul over a century ago, Local 47 promotes and Bill Reichenbach, Vivian Wolf Sternhagen protects the concerns of musicians in all areas of the music business. -

Download the Program (PDF)

PRIVATE PREMIERE EVENTJULY 19 2020 Thank you for joining us for the special premiere event. We are deeply grateful for your support! PROGRAM Approximate total run time: 2 hours PERFORMANCE PROGRAM welcome aaron copland Fanfare for the Common Man Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor and Colburn faculty reception and richard d. colburn award presentation horns trombones Andrew Bain, Colburn faculty and LA Phil Principal David Rejano Cantero, Colburn faculty intermission 5 minutes Elizabeth Upton, Colburn Conservatory alumna and LA Phil Principal the way forward film premiere and Colburn faculty Liam Wilt, Colburn Conservatory student Kaylet Torrez, Colburn Conservatory alumna and Callan Milani, Colburn Conservatory alumnus intermission 5 minutes Pacific Symphony Assistant Principal tuba Elyse Lauzon, Colburn Conservatory alumna, Ferran Martinez Miquel, Colburn Conservatory student live conversation with our artists Pacific Symphony section member timpani trumpets Ted Atkatz, Colburn faculty Jim Wilt, Colburn faculty and LA Phil Associate Principal bass drum Pat Chapman, Colburn Conservatory student Ryan Darke, Colburn Conservatory alumnus, THE WAY FORWARD Colburn faculty, and LA Opera Principal tam-tam Jonah Levy, Colburn Conservatory alumnus Arthur Lin, Colburn Conservatory student The Way Forward first took shape as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world and quickly imposed a new reality for musicians and dancers. In March 2020, the Colburn School began to reimagine the traditional performance-going routine as a new cinematic experience that could connect the School’s resilient johannes brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. 114 (IV. Allegro) artistic community with a global audience. Cristina Mateo Sáez, clarinet, Colburn Conservatory student Clive Greensmith, cello, Colburn faculty Faculty, alumni, and students from all units of the School, as well as guest artists, were enlisted to help Fabio Bidini, piano, Colburn faculty realize this new vision as well as director Hamid Shams. -

Married Life, for Better and Worse | Variety

Married life, for better and worse NOVEMBER 30, 2012 | 04:00AM PT Golden Globe Update 2013 Diane Garrett (http://variety.com/author/diane-garrett/) Leslie Mann wants you to know that the Viagra sex scene in “This Is 40 (http://variety.com/t/this-is-40/)” didn’t happen to her. Sure, the movie, one of several spotlighting the ups and downs of married life this awards season, draws on her union with writer-director Judd Apatow. And it stars their kids. But don’t confuse Pete and Debbie with Apatow and Mann. “That’s not us,” Mann quickly asserts with a laugh when the chemically enhanced coitus scene comes up in conversation. The scene, which opens the movie, sets (http://variety411.com/us/los-an- geles/sets-stages/) the stage for frank treatment of marital relations. Over the course of “This Is 40,” Mann’s Debbie and Paul Rudd’s Pete bicker about cupcakes, their parents and money. They also steal away for a romantic getaway from their squabbling kids and worry about their individual businesses. “I think it’s emotionally true to us, but also true to everyone,” Mann says, citing common marital complaints of feeling neglected or that the kids are getting more attention than the spouse. “It’s universal in that way.” Apatow collaborated with Mann on the script for years. “We come up with ideas, and the reason why fights are balanced in the film is because I try to figure out Pete and she helps me figure out Debbie,” Apatow says. The goal, Mann says, was to present a relationship that rings true, for better and for worse.