Mukbang and Food Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Ownership/Use

PT 04-1 Tax Type: Property Tax Issue: Religious Ownership/Use STATE OF ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS 3 ANGELS BROADCASTING NETWORK A.H. Docket # 01-PT-0027 P. I. # 174-116-11 v. Docket # 00-28-01 Docket # 01-28-07 THE DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS Barbara S. Rowe Administrative Law Judge RECOMMENDATION FOR DISPOSITION Appearances: Mr. Kent R. Steinkamp, Special Assistant Attorney General for the Illinois Department of Revenue; Mr. Nicholas P. Miller, Sidley, Austin, Brown, Wood, L.L.C., Mr. Lee Boothby, Boothby and Yingst, and Mr. D. Michael Riva for 3 Angels Broadcasting Network; Ms. Merry Rhodes and Ms. Joanne H. Petty, Robbins, Schwartz, Nicholas, Lifton and Taylor, Ltd. for Thompsonville Community High School District 112. Synopsis: The hearing in this matter was held to determine whether Franklin County Parcel Index No. 174-116-11 qualified for exemption during the 2000 and/or 2001 assessment years. Danny Shelton, president of Three Angels Broadcasting, (hereinafter referred to as the "Applicant" or “3ABN”); Larry Ewing, director of finance in 2002 of applicant; Alan Lovejoy, CPA and accountant; Walter Thompson, chairman of the board in 2002 of applicant; Bill Bishop, minister in the Seventh-day Adventist Church and member of the pastoral staff of applicant; Kenneth Denslow, president of the Illinois Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church; Mollie Steenson, department coordinator of applicant; and Linda Shelton, vice president of applicant, were present and testified on behalf of applicant. Cynthia Humm, Supervisor of Assessments of Franklin County was present and testified on behalf of Thompsonville Community High School District No. -

DFA Canada Global 50EQ-50FI Portfolio - Class F (USD) As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: RBC Holdings Are Subject to Change

DFA Canada Global 50EQ-50FI Portfolio - Class F (USD) As of July 31, 2021 (Updated Monthly) Source: RBC Holdings are subject to change. The information below represents the portfolio's holdings (excluding cash and cash equivalents) as of the date indicated, and may not be representative of the current or future investments of the portfolio. The information below should not be relied upon by the reader as research or investment advice regarding any security. This listing of portfolio holdings is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed a recommendation to buy the securities. The holdings information below does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The holdings information has not been audited. By viewing this listing of portfolio holdings, you are agreeing to not redistribute the information and to not misuse this information to the detriment of portfolio shareholders. Misuse of this information includes, but is not limited to, (i) purchasing or selling any securities listed in the portfolio holdings solely in reliance upon this information; (ii) trading against any of the portfolios or (iii) knowingly engaging in any trading practices that are damaging to Dimensional or one of the portfolios. Investors should consider the portfolio's investment objectives, risks, and charges and expenses, which are contained in the Prospectus. Investors should read it carefully before investing. This fund operates as a fund-of-funds and generally allocates its assets among other mutual funds, but has the ability to invest in securities and derivatives directly. The holdings listed below contain both the investment holdings of the corresponding underlying funds as well as any direct investments of the fund. -

Private Broadcasting and the Path to Radio Broadcasting Policy in Canada

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages 13–20 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v6i1.1219 Article Private Broadcasting and the Path to Radio Broadcasting Policy in Canada Anne Frances MacLennan Department of Communication Studies, York University, Toronto, M3J 1P3, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 6 October 2017 | Accepted: 6 December 2017 | Published: 9 February 2018 Abstract The largely unregulated early years of Canadian radio were vital to development of broadcasting policy. The Report of the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting in 1929 and American broadcasting both changed the direction of Canadian broadcasting, but were mitigated by the early, largely unregulated years. Broadcasters operated initially as small, indepen- dent, and local broadcasters, then, national networks developed in stages during the 1920s and 1930s. The late adoption of radio broadcasting policy to build a national network in Canada allowed other practices to take root in the wake of other examples, in particular, American commercial broadcasting. By 1929 when the Aird Report recommended a national net- work, the potential impact of the report was shaped by the path of early broadcasting and the shifts forced on Canada by American broadcasting and policy. Eventually Canada forged its own course that pulled in both directions, permitting both private commercial networks and public national networks. Keywords America; broadcasting; Canada; commission; frequencies; media history; national; networks; radio; religious Issue This article is part of the issue “Media History and Democracy”, edited by David W. Park (Lake Forest College, USA). © 2018 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

Trump Contracts COVID

MILITARY VIDEO GAMES COLLEGE FOOTBALL National Guard designates Spelunky 2 drops Air Force finally taking units in Alabama, Arizona players into the role the field for its first to respond to civil unrest of intrepid explorer game as it hosts Navy Page 4 Page 14 Back page Report: Nearly 500 service members died by suicide in 2019 » Page 3 Volume 79, No. 120A ©SS 2020 CONTINGENCY EDITION SATURDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2020 stripes.com Free to Deployed Areas Trump contracts COVID White House says president experiencing ‘mild symptoms’ By Jill Colvin and Zeke Miller Trump has spent much of the year downplaying Associated Press the threat of a virus that has killed more than WASHINGTON — The White House said Friday 205,000 Americans. that President Donald Trump was suffering “mild His diagnosis was sure to have a destabilizing symptoms” of COVID-19, making the stunning effect in Washington and around the world, announcement after he returned from an evening raising questions about how far the virus has fundraiser without telling the crowd he had been spread through the highest levels of the U.S. exposed to an aide with the disease that has government. Hours before Trump announced he killed a million people worldwide. had contracted the virus, the White House said The announcement that the president of the a top aide who had traveled with him during the United States and first lady Melania Trump week had tested positive. had tested positive, tweeted by Trump shortly “Tonight, @FLOTUS and I tested positive for after midnight, plunged the country deeper into COVID-19. -

Invocation Time to Tune in the Phenomenon of African American Religious Broadcasting

Invocation Time to Tune In The Phenomenon of African American Religious Broadcasting Shine on me, shine on me. Let the light from the lighthouse Shine on me. — “Shine on Me,” in African American Heritage Hymnal At the dawn of the twentieth century, W. E. B. Du Bois described the black preacher as “the most unique personality developed by the Negro on American soil.”1 For the majority of the century, because of societal constraints regulating the movement of persons of color in America, these spiritual poets were largely confned to preaching to their own racial and residential communities. Today, however, with the victo- ries of the civil rights era and the emergence of advanced forms of media communication, many of these dynamic personalities have gained wider visibility both nationally and internationally. To channel-surf from BET to TBN to MBC to the Word Network is to witness the creative genius and artistic imaginations of these religious fgures. And it would be vir- tually impossible to enter any African American Christian congregation and fnd someone who had not heard of such televangelists as Bishop T. D. Jakes, Bishop Eddie Long, and Pastor Crefo Dollar. These preach- ers seem to have become ubiquitous in black popular culture as a result of their constant television broadcasts, mass video distributions, printed publications, gospel stage plays, musical recordings, and gargantuan congregations. With an astute marketing consciousness, these preachers and their style of ministry have found an enduring place in the African American religious imagination. 1 2 Invocation Televangelism and the Black Church in America Any discussion of televangelism and the black church involves an engage- ment with two distinct areas of religious expression that have grown exponentially in the post−civil rights era: religious broadcasting and the megachurch movement. -

The Production of Religious Broadcasting: the Case of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository The Production of Religious Broadcasting: The Case of the BBC Caitriona Noonan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Cultural Policy Research Department of Theatre, Film and Television University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ December 2008 © Caitriona Noonan, 2008 Abstract This thesis examines the way in which media professionals negotiate the occupational challenges related to television and radio production. It has used the subject of religion and its treatment within the BBC as a microcosm to unpack some of the dilemmas of contemporary broadcasting. In recent years religious programmes have evolved in both form and content leading to what some observers claim is a “renaissance” in religious broadcasting. However, any claims of a renaissance have to be balanced against the complex institutional and commercial constraints that challenge its long-term viability. This research finds that despite the BBC’s public commitment to covering a religious brief, producers in this style of programming are subject to many of the same competitive forces as those in other areas of production. Furthermore those producers who work in-house within the BBC’s Department of Religion and Ethics believe that in practice they are being increasingly undermined through the internal culture of the Corporation and the strategic decisions it has adopted. This is not an intentional snub by the BBC but a product of the pressure the Corporation finds itself under in an increasingly competitive broadcasting ecology, hence the removal of the protection once afforded to both the department and the output. -

4 'He Who Has Ears to Hear, Let Him Hear

‘He Who Has Ears to Hear, Let Him Hear’: Christian Pedagogy and Religious Broadcasting During the Inter-War Period Michael Bailey Leeds Metropolitan University Keywords : Broadcasting, BBC religion, Christian Morality, Civilising Mission, Nation and Culture, Secularisation, Sabbatarianism, Ecumenicalism, Popular Religion and Entertainment. Abstract What I mean to demonstrate in this essay is the way in which early public service broadcasting developed as an extension of Christian pastoral guidance. Understood thus, early broadcasting can be seen to function as a socio-religious technology whose rationale was to give direction to practical conduct and attempt to hold individuals to it. The significance of this is that Christian utterance was a broadcasting activity to which the BBC, and its first Director-General particularly, John Reith, ascribed special importance. The BBC was determined to provide what it thought was for the moral good of the greater majority. In spite of overwhelming criticism from the listening public and secular public opinion, the BBC was unswerving in its commitment to the centrality of Christianity in the national culture. By the end of the 1930s the ‘Reithian Sunday’ was among the most enduring and controversial of the BBCs inter-war practices. Introduction In the entrance of Broadcasting House is a statue by the well-known sculptor, Eric Gill, depicting The Sower casting his seed abroad. Though the act of sowing is nowadays commonly associated with primitive farming methods, the iconography of the sower was in fact used to illustrate a well-known parable from the New Testament (Matthew 13; Mark 4; Luke 8). For just as Jesus told his disciples that the farmer goes out to sow his seed in order to yield a crop, so too do the agencies of religion sow the word of God in order that, ‘He who has ears to hear, let him hear’. -

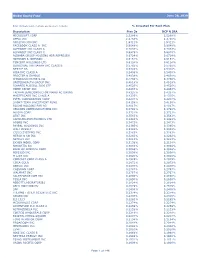

Global Equity Fund Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP

Global Equity Fund June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP 2.5289% 2.5289% APPLE INC 2.4756% 2.4756% AMAZON COM INC 1.9411% 1.9411% FACEBOOK CLASS A INC 0.9048% 0.9048% ALPHABET INC CLASS A 0.7033% 0.7033% ALPHABET INC CLASS C 0.6978% 0.6978% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING ADR REPRESEN 0.6724% 0.6724% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.6151% 0.6151% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.6124% 0.6124% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC CLASS B 0.5765% 0.5765% NESTLE SA 0.5428% 0.5428% VISA INC CLASS A 0.5408% 0.5408% PROCTER & GAMBLE 0.4838% 0.4838% JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 0.4730% 0.4730% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.4619% 0.4619% ISHARES RUSSELL 3000 ETF 0.4525% 0.4525% HOME DEPOT INC 0.4463% 0.4463% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING 0.4337% 0.4337% MASTERCARD INC CLASS A 0.4325% 0.4325% INTEL CORPORATION CORP 0.4207% 0.4207% SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT FUND 0.4158% 0.4158% ROCHE HOLDING PAR AG 0.4017% 0.4017% VERIZON COMMUNICATIONS INC 0.3792% 0.3792% NVIDIA CORP 0.3721% 0.3721% AT&T INC 0.3583% 0.3583% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS LTD 0.3483% 0.3483% ADOBE INC 0.3473% 0.3473% PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 0.3395% 0.3395% WALT DISNEY 0.3342% 0.3342% CISCO SYSTEMS INC 0.3283% 0.3283% MERCK & CO INC 0.3242% 0.3242% NETFLIX INC 0.3213% 0.3213% EXXON MOBIL CORP 0.3138% 0.3138% NOVARTIS AG 0.3084% 0.3084% BANK OF AMERICA CORP 0.3046% 0.3046% PEPSICO INC 0.3036% 0.3036% PFIZER INC 0.3020% 0.3020% COMCAST CORP CLASS A 0.2929% 0.2929% COCA-COLA 0.2872% 0.2872% ABBVIE INC 0.2870% 0.2870% CHEVRON CORP 0.2767% 0.2767% WALMART INC 0.2767% -

Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund Annual Report October 31, 2020

Annual Report | October 31, 2020 Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund See the inside front cover for important information about access to your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports. Important information about access to shareholder reports Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports will no longer be sent to you by mail, unless you specifically request them. Instead, you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted on the website and will be provided with a link to access the report. If you have already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and do not need to take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the fund electronically by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker-dealer or bank) or, if you invest directly with the fund, by calling Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or by logging on to vanguard.com. You may elect to receive paper copies of all future shareholder reports free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact the intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies. If you invest directly with the fund, you can call Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or log on to vanguard.com. Your election to receive paper copies will apply to all the funds you hold through an intermediary or directly with Vanguard. -

List of Search Engines

A blog network is a group of blogs that are connected to each other in a network. A blog network can either be a group of loosely connected blogs, or a group of blogs that are owned by the same company. The purpose of such a network is usually to promote the other blogs in the same network and therefore increase the advertising revenue generated from online advertising on the blogs.[1] List of search engines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For knowing popular web search engines see, see Most popular Internet search engines. This is a list of search engines, including web search engines, selection-based search engines, metasearch engines, desktop search tools, and web portals and vertical market websites that have a search facility for online databases. Contents 1 By content/topic o 1.1 General o 1.2 P2P search engines o 1.3 Metasearch engines o 1.4 Geographically limited scope o 1.5 Semantic o 1.6 Accountancy o 1.7 Business o 1.8 Computers o 1.9 Enterprise o 1.10 Fashion o 1.11 Food/Recipes o 1.12 Genealogy o 1.13 Mobile/Handheld o 1.14 Job o 1.15 Legal o 1.16 Medical o 1.17 News o 1.18 People o 1.19 Real estate / property o 1.20 Television o 1.21 Video Games 2 By information type o 2.1 Forum o 2.2 Blog o 2.3 Multimedia o 2.4 Source code o 2.5 BitTorrent o 2.6 Email o 2.7 Maps o 2.8 Price o 2.9 Question and answer . -

El Efecto Del “Hallyu” En La Estrategia De Soft Power De Corea Del Sur

FACULTAD DE DERECHO Carrera de Relaciones Internacionales EL EFECTO DEL “HALLYU” EN LA ESTRATEGIA DE SOFT POWER DE COREA DEL SUR Tesis para optar el Título Profesional de Licenciado en Relaciones Internacionales SANDRA LUCÍA OCAÑA BAUDOIN Asesor: Manuel Augusto Gonzales Chávez Lima – Perú 2019 A mi familia, por siempre creer en mí y apoyarme en cada paso de mi camino. AGRADECIMIENTOS Me gustaría expresar mi sincera gratitud a las personas que me brindaron su apoyo para el desarrollo de esta tesis: Manuel Gonzales Chávez, Enrique Cárdenas Aréstegui, Juan Carlos Liendo O’Connor, Pamela Olano de Cieza. Así mismo, extiendo mi agradecimiento al Ministro Seung-in Hong y a la Primera Secretaria Ye-seung Lee, de la embajada de Corea del Sur en Perú. Finalmente, agradezco a mi familia por su apoyo incondicional durante esta investigación. Resumen El presente trabajo busca analizar el efecto del fenómeno Hallyu en la estrategia de soft power de Corea del Sur. El Hallyu, también llamado “Ola Coreana”, es el proceso de difusión de la cultura popular surcoreana, que inició a mediados de los años noventa y se mantiene hasta el día de hoy. Considerando el alcance global que logró obtener dicho fenómeno – debido al éxito de productos culturales tales como las telenovelas y el K-pop – esta tesis busca responder cuál es su impacto en la estrategia de soft power surcoreana. La investigación – que es de tipo explicativo y enfoque cualitativo – se basó en distintas publicaciones académicas para comprender el desarrollo del fenómeno Hallyu y los elementos que lo constituyen. Además, determina los efectos económicos, socioculturales y políticos del fenómeno Hallyu. -

Collaborative Eating in Mukbang, a Korean Livestream of Eating HANWOOL CHOE Georgetown University, USA

Language in Society, page 1 of 38. doi:10.1017/S0047404518001355 Eating together multimodally: Collaborative eating in mukbang, a Korean livestream of eating HANWOOL CHOE Georgetown University, USA ABSTRACT Mukbang is a Korean livestream where a host eats while interacting with viewers. The eater ‘speaks’ to the viewers while eating and the viewers ‘type’ to each other and to the eater through a live chat room. Using interac- tional sociolinguistics along with insights from conversation analysis (CA) studies, the present study examines how sociable eating is jointly and multi- modally achieved in mukbang. Analyzing sixty-seven mukbang clips, I find that mukbang participants coordinate their actions through speech, written text, and embodied acts, and that this coordination creates involvement and, by extension, establishes both community and social agency. Specifi- cally, recruitments are the basic joint action of eating, as participants, who are taking turns, assume footings of the recruit and the recruiter. The host embodies viewers’ text recruitments through embodied animating and pup- peteering. As in street performance, the viewers often offer voluntary dona- tions, and the host shows entertaining gratitude in response. (Mukbang, footing, recruitments, agency, involvement, constructed action, multimodal interaction, computer-mediated discourse)* INTRODUCTION When individuals gather together around a table, eating becomes not only an oppor- tunity for nourishment, but also for sociability. In Korea, the practice of common eating is recognized as a cultural hallmark: people not only share a table, but also eat from the same dishes. Togetherness is thus a key feature of Korean eating. In recent years, however, the traditional practice of eating together has taken on a new multimodal form among Korea’s younger generation.