Firearms in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation Ballistics

An Overview of Forensic Ballistics Ankit Srivastava, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Institute of Forensic Science & Criminology Bundelkhand University, Jhansi – 284128, UP, India E-mail: [email protected] ; Mob: +91-9415067667 Ballistics Ballistics It is a branch of applied mechanics which deals with the study of motion of projectile and missiles and their associated phenomenon. Forensic Ballistics It is an application of science of ballistics to solve the problems related with shooting incident(where firearm is used). Firearms or guns Bullets/Pellets Cartridge cases Related Evidence Bullet holes Damaged bullet Gun shot wounds Gun shot residue Forensic Ballistics is divided into 3 sub-categories Internal Ballistics External Ballistics Terminal Ballistics Internal Ballistics The study of the phenomenon occurring inside a firearm when a shot is fired. It includes the study of various firearm mechanisms and barrel manufacturing techniques; factors influencing internal gas pressure; and firearm recoil . The most common types of Internal Ballistics examinations are: ✓ examining mechanism to determine the causes of accidental discharge ✓ examining home-made devices (zip-guns) to determine if they are capable of discharging ammunition effectively ✓ microscopic examination and comparison of fired bullets and cartridge cases to determine whether a particular firearm was used External Ballistics The study of the projectile’s flight from the moment it leaves the muzzle of the barrel until it strikes the target. The Two most common types of External Ballistics examinations are: calculation and reconstruction of bullet trajectories establishing the maximum range of a given bullet Terminal Ballistics The study of the projectile’s effect on the target or the counter-effect of the target on the projectile. -

Machine Guns

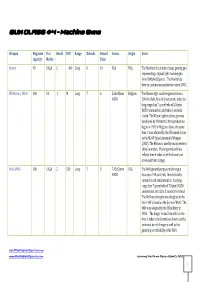

GUN CLASS #4 – Machine Guns Weapon Magazine Fire Recoil ROF Range Reloads Reload Ammo Origin Notes capacity Modes Time Morita 99 FA,SA 2 400 Long 6 10 N/A N/A The Morita is the standard issue gaming gun representing a typical light machine gun from Battlefield Sports. The Morita has been in continuous manufacture since 2002. FN Minimi / M249 200 FA 2 M Long 7 6 5.56x45mm Belgium The Minimi light machine gun features a NATO 200 shot belt, fires fully automatic only, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 5.56mm NATO ammunition, and takes 6 seconds reload. The Minimi light machine gun was developed by FN Herstal. Mass production began in 1982 in Belgium. About the same time it was adopted by the US Armed forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). The Minimi is used by many western allied countries. The longer reload time reflects time it takes to let the barrel cool down and then change. M60 GPMG 100 FA,SA 2 550 Long 7 8 7.62x51mm USA The M60 general purpose machine gun NATO features a 100 shot belt, fires both fully automatic and semiautomatic, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 7.62mm NATO ammunition and takes 8 seconds to reload. The M60 machine gun was designed in the late 1940's based on the German MG42. The M60 was adopted by the US military in 1950. .The longer reload time reflects the time it takes to let barrel cool down and the awkward barrel change as well as the general poor reliability of the M60. -

For Hard Chrome Plating (FNH1) 52 4.4

ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES & SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS Public version Legal name of Applicant(s): FN Herstal Manroy Submitted by: FN Herstal Substance: Chromium trioxide (EC 215-607-8, CAS 1333-82-0) Use title: Use-1 Industrial use of chromium trioxide in the hard chromium coating of military small- and medium-caliber firearms barrel bores and auxiliary parts subject to thermal, mechanical and chemical stresses, in order to provide hardness, heat resistance and thermal barrier properties, as well as corrosion resistance, adhesion and low friction properties. Use number: 1 Analysis of Alternatives – Socio-Economic Analysis CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 7 2. AIMS AND SCOPE OF THE ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................... 9 2.1. Applicants ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1.1. FN Herstal ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1.2. Manroy ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Behind a Veil of Secrecy:Military Small Arms and Light Weapons

16 Behind a Veil of Secrecy: Military Small Arms and Light Weapons Production in Western Europe By Reinhilde Weidacher An Occasional Paper of the Small Arms Survey Copyright The Small Arms Survey Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Grad © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva 2005 uate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It is also linked to the Graduate Institute’s Programme for Strategic and International Security First published in November 2005 Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Depart a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the ment of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Australia, prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permit Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, ted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It collaborates with research insti organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above tutes and nongovernmental organizations in many countries including Brazil, should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address Canada, Georgia, Germany, India, Israel, Jordan, Norway, the Russian Federation, below. South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey occasional paper series presents new and substan Graduate Institute of International Studies tial research findings by project staff and commissioned researchers on data, 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland methodological, and conceptual issues related to small arms, or detailed Copyedited by Alex Potter country and regional case studies. -

XXXV, 2 April-June 2019 Editor's Note 3 Prabhat Patnaik Some

XXXV, 2 April-June 2019 Editor’s Note 3 Prabhat Patnaik Some Comments About Marx’s Epistemology 7 Raghu Defence Procurement Today: Threat to Self-Reliance and Strategic Autonomy 16 CC Resolution (2010) On the Jammu & Kashmir Issue 57 EDITORIAL BOARD Sitaram YECHUry (EDItor) PrakasH Karat B.V. RAGHavULU ASHok DHAWALE ContribUtors Prabhat Patnaik is Emeritus Professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Raghu is a Defence and Strategic Analyst based in New Delhi. For subscription and other queries, contact The Manager, Marxist, A.K. Gopalan Bhavan, 27-29 Bhai Veer Singh Marg, New Delhi 110001 Phone: (91-11) 2334 8725. Email: [email protected] Printed by Sitaram Yechury at Progressive Printers, A 21, Jhilmil Industrial Area, Shahdara, Delhi 110095, and published by him on behalf of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) from A.K.Gopalan Bhavan, 27-29 Bhai Veer Singh Marg, New Delhi 110001 Marxist, XXXV, 2, April-June 2019 RAGHU Defence Procurement Today Threat to Self-Reliance and Strategic Autonomy IntrodUction India was the world’s second largest importer of military hardware during 2014-18 accounting for 9.5 per cent of the total, having dropped from its first rank during 2009-13 and ceding top spot to Saudi Arabia which accounted for around 12.5 per cent of total imports during these last five years.1 However, this was mainly due to delays in deliveries of earlier orders to India, and a sporadic spurt in Saudi imports. One can therefore broadly say that India has been the world’s leading arms importer over the past decade. -

B.O.O.S. Book of Operational Sculpture

B.O.O.S. Book of operational sculpture B.O.O.S. – Book of Operational Sculpture 1 Dear reader Thank You, that You took our book. We would like to introduce You our technique of sculpturing fashionable apparel, protection and field gear. Our techniques are based on the assessment of toughest world natural and man made environments and threats, special task operations and assigments of elite skilled operational units. Following book we describe how toughest operational requirements, transformed into basic quality system requirements of apparel, protection and field gear through deep scientific proceedings. Thus guarantee creation of fashionable, health and life saving apparel, protection and field gear. We hope this is exactly You are looking for. We will be happy if You can share with us Your experience in the toughest environments of the world. With the best regards Dr. Igors Šitvjenkins B.O.O.S. – Book of Operational Sculpture 3 4 B.O.O.S. – Book of Operational Sculpture INTRIODUCTION 6 TRINITY OF OPERATIONS 7 Model of most demanding operations CRITICAL SKILLS OPERATIONAL UNIT 10 Model of most elite special task unit OPERATIONAL TERRAIN 17 Assessment of toughest environments COMBAT PHYSIOLOGY 30 Body reaction on weather, apparel, load, terrain, task DESIGN 49 Bio-mechanics, neurodynamics, fashion, deception CAMOUFLAGE 52 TripleX multi-terrain pattern, NIR, TIR PROTECTION AGAINST FLAME THREATS 57 Trade-offs, FR of layering, System testing, SOPs REFERENCES ? B.O.O.S. – Book of Operational Sculpture 5 Introduction 1. Combat environment is the toughest. Knowing how to transform combat environment in fashionable apparel is what we are standing for to satisfy customer demanding needs, including civil customers, looking for high valuable apparel, protection and field gear (APFG), providing modern fashion and protection against tough environment our customers going to stay in. -

Table 20C.1 CENTRAL BOARD of DIRECT TAXES

Table 20C.1 CENTRAL BOARD OF DIRECT TAXES STATEMENT SHOWING DETAILS OF PROSECUTIONS UNDER THE DIRECT TAXES ENACTMENTS DURING THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2014‐2015, 2015‐2016 and 2016‐2017 A. RESULT OF SEARCHES Financial Year Value of assets Seized (Rs. in Crores) 2014‐15 761.70 2015‐16 712.32 2016‐17 1469.45 B. STATISTICS FOR PROSECUTION Financial Number Number of Number of Number of Number of Year proceedings proceedings Persons of prosecutio compounded where convictions Convicted proceedin n obtained finally & jailed gs proceedin acquitted gs launched (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) 2014‐15 669 900 34 NA * 42 2015‐16 552 1019 28 NA * 38 2016‐17 1252 1208 16 19 30 # Figure also includes the no. of cases in Col. 6 in which proceedings were compounded & launched from previous year. * The data w.r.t. to the conviction in Col. 5 was not maintained centrally prior to F.Y. 2016‐17. TABLE 20C.1 – Page 1 of 1 Table 20C.2 CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, NEW DELHI PREVENTION OF CORRUPTION ACT CASES AND THEIR DISPOSAL‐ 2016 A. CBI Disposal 1(a) No. of cases pending investigation from previous year. 571 (b) No. of cases registered during the year. 673 (c) Total No. of cases for investigation during the year. 1244 2. No. of cases recommended for trial during the year. (Charge sheets filed) 339 3. No. of cases sent up for trial and also reported for departmental action during the year. 184 Total (2 + 3) 523 4. No. of cases pending departmental sanction for prosecution during the year. -

Small Arms of the Indian State: a Century of Procurement And

INDIA ARMED VIOLENCE ASSESSMENT Issue Brief Number 4 January 2014 Small Arms of the Indian State A Century of Procurement and Production Introduction state of dysfunction’ and singled out nuclear weapons (Bedi, 1999; Gupta, Army production as particularly weak 1990). Overlooked in this way, the Small arms procurement by the Indian (Cohen and Dasgupta, 2010, p. 143). Indian small arms industry developed government has long reflected the coun- Under this larger procurement its own momentum, largely discon- try’s larger national military procure- system, dominated by a culture of nected from broader international ment system, which stressed indigenous conservatism and a preference for trends in armament design and policy. arms production and procurement domestic manufacturers, any effort to It became one of the world’s largest above all. This deeply ingrained pri- modernize the small arms of India’s small arms industries, often over- ority created a national armaments military and police was held back, looked because it focuses mostly on policy widely criticized for passivity, even when indigenous products were supplying domestic military and law lack of strategic direction, and deliv- technically disappointing. While the enforcement services, rather than civil- ering equipment to the armed forces topic of small arms development ian or export markets. which was neither wanted nor suited never was prominent in Indian secu- As shown in this Issue Brief, these to their needs. By the 1990s, critics had rity affairs, it all but disappeared trends have changed since the 1990s, begun to write of an endemic ‘failure from public discussion in the 1980s but their legacy will continue to affect of defense production’ (Smith, 1994, and 1990s. -

Dominican Republic Country Report

SALW Guide Global distribution and visual identification Dominican Republic Country report https://salw-guide.bicc.de Weapons Distribution SALW Guide Weapons Distribution The following list shows the weapons which can be found in Dominican Republic and whether there is data on who holds these weapons: AR 15 (M16/M4) U HK MP5 G Browning M 2 G M1919 Browning G Colt M1911 U M203 grenade launcher G FN FAL G M60 G FN Herstal FN MAG G M79 G FN High Power U Mossberg 500 U FN MINIMI G MP UZI G FN P90 G Sterling MP L2A3 G HK G3 G Thompson M1928 G Explanation of symbols Country of origin Licensed production Production without a licence G Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by Governmental agencies. N Non-Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by non-Governmental armed groups. U Unspecified: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is found in the country, but do not specify whether it is held by Governmental agencies or non-Governmental armed groups. It is entirely possible to have a combination of tags beside each country. For example, if country X is tagged with a G and a U, it means that at least one source of data identifies Governmental agencies as holders of weapon type Y, and at least one other source confirms the presence of the weapon in country X without specifying who holds it. Note: This application is a living, non-comprehensive database, relying to a great extent on active contributions (provision and/or validation of data and information) by either SALW experts from the military and international renowned think tanks or by national and regional focal points of small arms control entities. -

Simunitions Pricing

2-U.S. LAW ENFORCEMENT/CRP Effective April 1st, 2021 (Supersede previous version) ALTHOUGH BEST EFFORTS ARE MADE TO ENSURE ACCURACY OF THIS PRICE LIST, GENERAL DYNAMICS ORDNANCE AND TACTICAL SYSTEMS-CANADA INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO CORRECT ANY ERRORS CONTAINED GENERAL PURCHASING INFORMATION WITHIN. GENERAL PURCHASING INFORMATION ITAR: Certain products in this price list are subject to United States International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). Products controlled by ITAR regulations are denoted by one asterisk (*). GAC: Certain products in this price list are subject to Global Affairs Canada (GAC). Products controlled by GAC Export Controls are denoted by two asterisks (**). ITAR and GAC: Certain products in this price list are subject to both, United States International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and, Global Affairs Canada (GAC). They are denoted by three asterisks (***). Pricing : Prices are expressed in U.S. Dollars and subject to change without notice. Pricing is only for commercial standard packaging. Excise Tax : In the U.S.A. Simunition products are imported by General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems - Simunition® Operations. An 11 % Federal excise tax will be added, if applicable. Special Labelling Fees : Charges related to special labelling will be of $5.00 per unit label. Terms : Payments are as specified on all invoices, except where otherwise provided in contracts or other special terms. Title of the goods remain in possession of the seller until full payment is received from the customer. Payments for invoices received after the net terms will accrue an interest penalty of 1.5 % per month (18 % annual). If a customer fails to honor his terms, full payment of all receivables will become due. -

Small Arms for Urban Combat

Small Arms for Urban Combat This page intentionally left blank Small Arms for Urban Combat A Review of Modern Handguns, Submachine Guns, Personal Defense Weapons, Carbines, Assault Rifles, Sniper Rifles, Anti-Materiel Rifles, Machine Guns, Combat Shotguns, Grenade Launchers and Other Weapons Systems RUSSELL C. TILSTRA McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Tilstra, Russell C., ¡968– Small arms for urban combat : a review of modern handguns, submachine guns, personal defense weapons, carbines, assault rifles, sniper rifles, anti-materiel rifles, machine guns, combat shotguns, grenade launchers and other weapons systems / Russell C. Tilstra. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6523-1 softcover : acid free paper 1. Firearms. 2. Urban warfare—Equipment and supplies. I. Title. UD380.T55 2012 623.4'4—dc23 2011046889 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2012 Russell C. Tilstra. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Front cover design by David K. Landis (Shake It Loose Graphics) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my wife and children for their love and support. Thanks for putting up with me. This page intentionally left blank Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations . viii Preface . 1 Introduction . 3 1. Handguns . 9 2. Submachine Guns . 33 3. -

AK 47 RIFLE 29823 Nos 6

Appendix-"A” PROCUREMENT PLAN- 2017 SNo. Name of Items Quantity SNo. Name of Items Quantity A&A. (Genl) 1 AK 47 RIFLE 29823 Nos 6 Assault Rifles (7.62 x 39 MM with 45867 Nos Accessories) 2 SNIPER RIFLE 252 Nos 7 PNV Sight for 5.56 INSAS Rifle 1750 Nos 3 MP-5 A3 SMG 1166 Nos 8 Assault Rifles 59,645 Nos 4 GLOCK - 17 PISTOL 720 Nos 9 MGL- (XRGL-40) PAC Basis 10 Nos 5 UBGL & Matching Grenades 1970 Nos 1,08,062 Nos C&T(Genl) 10 SOCKS WOOLEN HY KHAKI 60732 Nos 18 BOOT ANKLE TEXTILE(JUNGLE 30000 Nos BOOT) 11 TROUSER ECC 20643 Nos 19 TENT EXTENDABLE (4M) 4000 Nos 12 SPARE GLASSES FOR GOGGLES 27180 Nos 20 PF HUTS (243 NOS) 243 Nos GS 13 RESCUE BAG 203 Nos 21 PF HUTS (1133 NOS) 1133 Nos 14 CARRIER MAN PACK 17965 Nos 22 PF HUTS (1105 NOS) 1105 Nos 15 HOT WATER BOTTLE RUBBER 2899 Nos 23 BULLET RESISTANT JACKET 27412 Nos 16 WINTER OVERALL 7186 Nos 24 BULLET RESISTANT HELMET 20000 Nos 17 BULLET PROOF PATKA 20000 Nos 25 B.R.Vest 806 Nos M&E (Genl) 26 Non Linear Junction Detector 40 Nos 42 Tactical Blanket System 02 set 27 Fiber Optic Scope 32 Nos 43 Ni-mH Battery Pack For 5w 6440 Nos Hand Held VHF Radio Sets 28 Contactless Stethoscope 02 Nos 44 Li-ion Battery Pack 14.8 V for 372 Nos VX-1210 29 21 different types of BDD Eqpts 21 Nos 45 HF Manpack Transceiver Sets 25 300 Nos- for 10 CoBRA Units and W Rajasthan Sector (11 Nos) 30 DSMD 34 nos 46 Laser Printers for Crypto 248 Nos- Centre’s 31 HHTI (Un-cooled) short range 496 Nos 47 Line Interactive UPS 1KVA for 248 Nos Crypto Centre’s 32 DSMD 696 Nos 48 1/5, 25W VHF with Assys for 6335 Nos - North East based