General Disclaimer One Or More of the Following Statements May Affect This Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Earth's Magnetism

THE STUDY OF EARTH’S MAGNETISM (1269-1950): A FOUNDATION BY PEREGRINUS AND SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENT OF GEOMAGNETISM AND PALEOMAGNETISM Vincent Courtillot, Jean-Louis Le Mouël To cite this version: Vincent Courtillot, Jean-Louis Le Mouël. THE STUDY OF EARTH’S MAGNETISM (1269-1950): A FOUNDATION BY PEREGRINUS AND SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENT OF GEOMAGNETISM AND PALEOMAGNETISM. Reviews of Geophysics, American Geophysical Union, 2007, 45 (3), pp.RG3008. 10.1029/2006RG000198. insu-02448801 HAL Id: insu-02448801 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-02448801 Submitted on 22 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE STUDY OF EARTH’S MAGNETISM (1269–1950): A FOUNDATION BY PEREGRINUS AND SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENT OF GEOMAGNETISM AND PALEOMAGNETISM Vincent Courtillot1 and Jean-Louis Le Moue¨l1 Received 17 February 2006; revised 14 July 2006; accepted 18 September 2006; published 25 September 2007. [1] This paper summarizes the histories of geomagnetism induced magnetizations), Delesse (remagnetization in a and paleomagnetism (1269–1950). The role of Peregrinus direction opposite to the original), and Melloni (direction of is emphasized. In the sixteenth century a debate on local lava magnetization acquired at time of cooling). -

Survey of Magnetism and Electrodynamics (Chapters 5-11)

Survey of Magnetism and Electrodynamics (Chapters 5-11) * Electrostatics - Coulomb’s law * Magnetostatics - Biot-Savart law closed V=1 potential ”flow “ I=1 V=2 I=2 surfaces discontinuity I=0 I = 6 ! I=6 closed flux divergent field lines B I=3 curling flow ”flux “lines D I=4 surfaces of H from source Q I=5 around source I * Helmholtz theorem: source and potential * Green ‘s function (tent/pole) * Macroscopic media - polarization chains * magnetization chains free charge in conductor M-chain bound charge (solenoid) in dielectric magnetic coil * Faraday’s law * Maxwell’s displacement current * Three electrical devices, each the ratio of flux / flow CAPACITOR RESISTOR INDUCTOR * Electrodynamics equations Lorentz force Continuity Maxwell electric, magnetic fields Constitution Potentials (wave equation) Gauge transform * Conserved currents desity flux energy momentum * Electromagnetic waves - Fresnell’s coefficients - skin depth - dipole radiation Section 5.1.1 – Magnetic Fields * the magnetic force was known in antiquity, but was more difficult to quantify ~ predominant effect in nature involves magnetization, not electric currents ~ no magnetic (point) charge (monopole); 1-d currents instead of 0-d charges ~ static electricity was produced in the lab long before steady currents * History: http://maxwell.byu.edu/~spencerr/phys442/node4.html 600 BC Thales of Miletus discovers lodestone’s atraction to iron 1200 AD Chinese use lodestone compass for navigation 1259 AD Petrus Peregrinus (Italy) discovers the same thing 1600 AD William Gilbert -

Magnetic Rocks © Learning A–Z Learning A–Z J Written by Katherine Follett Lexile 470L

FOCUS Book Magnetic Make a magnet! Get a strong magnet and a thin metal bolt. Rub the bolt Rocks across the magnet in one direction fifty times. Pick up a staple with the bolt. You made a magnet! Design a test for your magnet. What can it pick up? What else can you test? Now make another magnet with a new bolt. Change one thing about how you make the magnet. Then repeat your test. How did the results change? Beyond the Book Go to two places with sand. Find out which kind of sand has the most magnetite. Metal and Magnets Magnetic Have you ever played with magnets? Maybe there are magnets on your Rocks refrigerator. Some toys also have magnets in them. A magnet is a special piece of metal. It pulls on, or attracts, other pieces FOCUS Question of metal. What kinds of natural materials stick to magnets? But where do magnets come from? Cause and Effect Photo Credits: Front cover: © Joel Arem/Science Source/Getty Images; page 2: © Vanessa Davies/DK Images; page 3: © Art Directors & TRIP/Alamy Stock Photo; page 4: © Richard Hutchings/Science Source; page 5 (top): © Charles O’Rear/Corbis/VCG/Corbis Documentary/Getty Images; page 5 (bottom): © David Lee/ Alamy Stock Photo; page 6 (left): Sarah Cebulski/© Learning A–Z; page 6 (right): © Alexandru Dobrea/ Hemera/Thinkstock; page 7 (top): © Visuals Unlimited/Getty Images; page 7 (bottom): © Liu Liqun/Corbis Documentary/Getty Images; page 9: © The Natural History Museum/Alamy Stock Photo Illustration Credits: Page 8: Signe Nordin/© Learning A–Z; border (rock): Nora Voutas/© Learning A–Z; (clip): Casey Jones/ © Learning A–Z Reading Levels Magnetic Rocks © Learning A–Z Learning A–Z J Written by Katherine Follett Lexile 470L Correlations All rights reserved. -

Electricity and Magnetism

3637_CassidyTX_10b 6/14/02 12:47 PM Page 459 CHAPTER - 10 + Electricity and Magnetism 10.1 Gilbert’s Magnets 10.2 Electric Charges and Electric Forces 10.3 Forces and Fields 10.4 Electric Currents 10.5 Electric Potential Difference 10.6 Electric Potential Difference and Current 10.7 Electric Potential Difference and Power 10.8 Currents Act on Magnets 10.9 Currents Act on Currents 10.10 Magnetic Fields and Moving Charges 10.1 GILBERT’S MAGNETS Two natural substances, amber and lodestone, have awakened curiosity since ancient times. Amber is sap that oozed long ago from certain softwood trees, such as pine. Over many centuries, it hardened into a semitranspar- ent solid akin to model plastics and ranging in color from yellow to brown. It is a handsome ornamental stone when polished, and sometimes contains the remains of insects that were caught in the sticky sap. Ancient Greeks recognized a strange property of amber. If rubbed vigorously against cloth, it can attract nearby objects, such as bits of straw or grain seeds. Lodestone is a metallic mineral that also has unusual properties. It at- tracts iron. Also, when suspended or floated, a piece of lodestone always turns to one particular position, a north–south direction. The first known written description of the navigational use of lodestone as a compass in Western countries dates from the late twelfth century, but its properties were known even earlier in China. Today, lodestone would be called mag- netized iron ore. 459 3637_CassidyTX_10b 6/14/02 12:47 PM Page 460 460 10. -

5 Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism

5 Geomagnetism and paleomagnetism It is not known when the directive power of the magnet 5.1 HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION - its ability to align consistently north-south - was first recognized. Early in the Han dynasty, between 300 and 5.1.1 The discovery of magnetism 200 BC, the Chinese fashioned a rudimentary compass Mankind's interest in magnetism began as a fascination out of lodestone. It consisted of a spoon-shaped object, with the curious attractive properties of the mineral lode whose bowl balanced and could rotate on a flat polished stone, a naturally occurring form of magnetite. Called surface. This compass may have been used in the search loadstone in early usage, the name derives from the old for gems and in the selection of sites for houses. Before English word load, meaning "way" or "course"; the load 1000 AD the Chinese had developed suspended and stone was literally a stone which showed a traveller the pivoted-needle compasses. Their directive power led to the way. use of compasses for navigation long before the origin of The earliest observations of magnetism were made the aligning forces was understood. As late as the twelfth before accurate records of discoveries were kept, so that century, it was supposed in Europe that the alignment of it is impossible to be sure of historical precedents. the compass arose from its attempt to follow the pole star. Nevertheless, Greek philosophers wrote about lodestone It was later shown that the compass alignment was pro around 800 BC and its properties were known to the duced by a property of the Earth itself. -

8.4 History of the Magnetic Method in Exploration There Is Little Doubt That the Chinese Were the First to Observe and Employ Th

8.4 History of the magnetic method in exploration There is little doubt that the Chinese were the first to observe and employ the directional properties of magnetic objects in navigation. They may have invented and used the compass as early as 2600 before the Common Era, but more likely it was as late as 1100 in the Common Era before the compass was used as a navigational instrument. The compass was first noted in Europe around 1200, but the reference by an English monk suggests that the compass had previously been known for an extended period of time. In 1269, P. de Maricourt (P. Peregrinus) investigated the properties of a spherical lodestone. He studied the dipolar nature of magnetic objects and named the poles after the geographic directions that they pointed to (i.e. north and south). He also identified the forces of attraction between unlike poles and the repulsion between like poles. Although the matter was possibly observed earlier by the Chinese and also by Christopher Columbus in his voyages of discovery of the Caribbean Islands in 1492, N. Hartmann in 1510 is credited as the first European to record the declination of the geomagnetic field. In 1544, he was also the first to observe the inclination of the field. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, R. Norman constructed the first inclinometer with the dipping magnetic needle located on a horizontal pivot. With it he was able to show that the inclination of the field corresponds to that on a spherical lodestone, indicating that the cause of the directional component of the compass was within the Earth. -

Magnets and Magnetism by Encyclopaedia Britannica, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 08.21.19 Word Count 447 Level 420L

Magnets and magnetism By Encyclopaedia Britannica, adapted by Newsela staff on 08.21.19 Word Count 447 Level 420L Image 1. Metal paperclips stick to a lodestone rock. Lodestone is a natural magnet. Photo by: Ryan Somma/Flickr A magnet is made of rock or metal. It can pull some types of metal toward itself. The pulling force of magnets is called magnetism. It is a natural force. What Causes Magnetism? Magnets exist in nature. Certain rocks are magnets. One type of magnetic rock is lodestone. Magnetism is caused by tiny particles. They are called electrons. These particles are found in atoms. Atoms are the building blocks of everything. They are made of electrons and other particles. The electrons rotate around the atom's center. They make tiny magnetic forces. Sometimes many electrons spin in the same direction. Their tiny magnetic forces join together. They make one big magnet. You can use one magnet to make another. You rub the magnet on a piece of metal. You rub in only one direction. This makes the electrons in the metal start spinning. They all spin in the same direction. This is how they make a new magnet. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. Electricity can also make magnets. It is a form of energy. It is made by flowing electrons. Electricity can be used to make special magnets. They are called electromagnets. Hard And Soft Magnets Some metals make good magnets. One example is nickel. Another is iron. Once they become magnets, they stay magnets. -

Strange Attraction Civity)

HISTORICAL NOTE and then quenched to freeze in the nec essary hardness and magnetic traits (such as improved retentivity and coer Strange Attraction civity). After 1855 it was known that adding tungsten or manganese Each year, several million tOns of Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt (Peter improved carbon steel as a permanent metal are produced for use as magnetic the Pilgrim) described in detail the use magnet. materials in many everyday devices and of a compass for navigation. He processes common to all of us-from believed that the lodestone derived its Many different families of magnetic radio communication, information stor power from the sky. Apparently on one alloys have come into use since the age, telephone receivers, and stereo of his long voyages, Peter the Pilgrim beginning of this century. At the turn of speakers to electric motors, transform played with a sphere of magnetite, the 20th century Sir Robert Hadfield ers, and generators. All these things exploring its surface with bits of iron. invented iron-silicon alloys, which have would have completely baffled the He discovered that lines of magnetic especially high permeabilities in the ori shepherd Magnes 2500 years ago when, force circled the sphere and seemed to entation in which the alloy passes according to legend, he stepped on a intersect at two opposite places on the through the rolling press. Chrome-steel lodestone (magnetite). Pliny the Elder globe, which he named "poles" in anal alloys were developed in 1917, and until wrote of Magnes, "the nails of whose ogy to the Earth's poles. It wasn't until 1930 the only commercially available shoes and the [iron] tip of whose staff more than three centuries later in 1600, permanent magnets were made of car stuck fast in a magnetick field while he though, that William Gilbert, physician bon-steel, chrome-steel, or tungsten pastured his flocks." to Queen Elizabeth I, proposed that the steel. -

The Study of Magnetism and Terrestrial Magnetism in Great Britain, C 1750-1830 Robinson Mclaughry Yost Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Lodestone and earth: the study of magnetism and terrestrial magnetism in Great Britain, c 1750-1830 Robinson McLaughry Yost Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Yost, Robinson McLaughry, "Lodestone and earth: the study of magnetism and terrestrial magnetism in Great Britain, c 1750-1830 " (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11758. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11758 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

LODESTONE PACIFIC "Finest in the Field"

LODESTONE PACIFIC "Finest In The Field" VARIABLE SHIELDED COIL FORMS Hardware Only or Finished Wound Assemblies For Tunable Inductors, Transformers and Oscillators • Th r o u g h ho l e • Su r f a c e Mo u n T Issue K Rev. 1 4769 Wesley Dr., Anaheim, CA 92807 USA • Phone (714) 970-0900 • Fax (714) 970-0800 E-Mail: [email protected] • www.lodestonepacific.com LODESTONE PACIFIC Tuneable Shielded Coil Forms High Q • Dependable Performance • Superior Temperature Stability • RoHS and REACH Compliant “Finest in the Field” China USA Mandy Tina KaAmyrin Lodestone China P. Leo Ltd Lodestone USA Hong Kong Lodestone USA Shenzhen California [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (86)+86 1363 136-3166-2432 166 2432 (852)+852 2604260 48222 8222 1 (714)+1(800) 970 694-8089 0900 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From Fish Finder to Sidewinder Variable Shielded Coil Forms for making Variable Inductors, IFT Coils, Oscillators, RF Coils, Transformers, RF Filter Inductors, Narrow and 5mm Toko Sizes Broadband RF Transformers, AM and FM OSC Coils, RF Antenna Coils, TV Receiver Coils, Transceiver Coils, and IFT Amplifiers. Lodestone Pacific Popular Assemblies High Q • Great Temperature Stability USA Military Qualified ISO 9001-2000 • 8mm Assemblies Using Iron Powder Cores Lodestone L32, L33, L335 & L337 series • 10.5 & 11mm Assemblies Using Iron Powder Cores Lodestone L42, L41, L43 series • 11.5 & 14.5mm Assemblies Using Iron Powder Cores 7mm Toko Sizes Lodestone L45, L57 series -

Current Electricity Electromagnet Electron Force Lodestone Magnet

Name ___________________________ Date ___________________ Magnetism & Electricity Vocabulary List & Definitions current the flow of electricity in a conductor. a physical phenomenon caused by the movement of certain charged particles such as electrons, esp. between points having different electrical charges, and seen in electricity naturally occurring phenomena such as lightning and magnetic attraction and repulsion. a magnet in which an iron or steel core is magnetized by the electric current in the coil of insulated wire wound electromagnet around it. a negatively charged particle, considered a fundamental unit of matter, that exists independently or outside the electron nucleus of an atom. force active power, energy, or physical strength. a rock that possesses magnetic properties and attracts lodestone iron; magnetite. an object that attracts iron and some other materials by magnet virtue of a natural or induced force field surrounding it. to cause to come near, as by some special quality or attract action. a device that generates electricity by means of chemical battery reactions. repel to drive away or force backwards. an arrangement of electronic elements, including conductors, resistors, and the like, through which electric circuit current moves. an instrument for determining direction, esp. one with a horizontal magnetic needle that rotates freely until it compass points to the magnetic north. ©Teachnology, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 1 Name ___________________________ Date ___________________ Magnetism and Electricity Word Search -

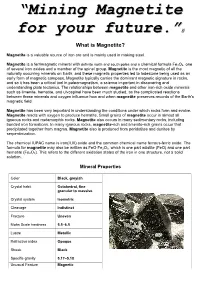

“Mining Magnetite for Your Future.”

““MMiinniinngg MMaaggnneettiittee © ffoorr yyoouurr ffuuttuurree..”” What is Magnetite? Magnetite is a valuable source of iron ore and is mainly used in making steel. Magnetite is a ferrimagnetic mineral with definite north and south poles and a chemical formula Fe3O4, one of several iron oxides and a member of the spinel group. Magnetite is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth, and these magnetic properties led to lodestone being used as an early form of magnetic compass. Magnetite typically carries the dominant magnetic signature in rocks, and so it has been a critical tool in paleomagnetism, a science important in discovering and understanding plate tectonics. The relationships between magnetite and other iron-rich oxide minerals such as ilmenite, hematite, and ulvospinel have been much studied, as the complicated reactions between these minerals and oxygen influence how and when magnetite preserves records of the Earth's magnetic field. Magnetite has been very important in understanding the conditions under which rocks form and evolve. Magnetite reacts with oxygen to produce hematite. Small grains of magnetite occur in almost all igneous rocks and metamorphic rocks. Magnetite also occurs in many sedimentary rocks, including banded iron formations. In many igneous rocks, magnetite-rich and ilmenite-rich grains occur that precipitated together from magma. Magnetite also is produced from peridotites and dunites by serpentinization. The chemical IUPAC name is iron(II,III) oxide and the common chemical name ferrous-ferric oxide. The formula for magnetite may also be written as FeO·Fe2O3, which is one part wüstite (FeO) and one part hematite (Fe2O3).