'There's a Sound of Many Voices in the Camp and on the Track' –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singing Our National Anthem

Singing our National Anthem It is traditional for many Lodges to sing our national anthem ‘God Defend New Zealand’ at regular meetings or particularly at installation meetings. This can be either during the installation ceremony or during refectory. ‘God Defend New Zealand’ is one of two official anthems. The second, ‘God save the Queen’, reflects our colonial past. ‘God defend New Zealand’ was elevated to anthem status in 1977 and has become the preferred anthem for New Zealanders both at home and abroad. ‘God save the Queen’ is usually reserved for formal ceremonies involving the Queen, the Governor-General or the royal family. Thomas Bracken’s poem, ‘God defend New Zealand’, was put to music in 1876 by J.J. Woods from Lawrence, Central Otago. The first Maori translation was made in 1878 by Native Land Court judge Thomas H. Smith, at the request of Governor Sir George Grey. Despite this, until the closing decades of the 20th century most New Zealanders were familiar only with the English-language version. This situation changed dramatically at the 1999 Rugby World Cup in England. Hinewehi Mohi sang ‘God defend New Zealand’ only in Te Reo Maori before the All Blacks versus England match. While it has been customary for Lodges to sing the ‘English’ version younger men have grown up with the anthem being sung in both Maori and English, to acknowledge our bicultural heritage, particularly before major sporting events. Accordingly if we wish to ensure Freemasonry is attractive and contemporary to younger men it is important that Lodges look at adopting the dual version when the anthem is sung during Lodge activities. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Steve Harley Lee Nelson

SPARKLING ARTS EVENTS IN THE HEART OF SHOREHAM SEPT – DEC 2014 BAKA BEYOND LUNASA THE INNER VISION ORCHESTRA STEVE HARLEY GEORGIE FAME LEE NELSON TOYAH WILLCOX CURVED AIR SHAKATAK ROPETACKLECENTRE.CO.UK SEPT 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 SEPT 2014 WELCOME TO ROPETACKLE From music, comedy, theatre, talks, family events, exhibitions, and much more, we’ve something for everybody to enjoy this autumn and winter. As a charitable trust staffed almost entirely by volunteers, nothing comes close to the friendly atmosphere, intimate performance space, and first- class programming that makes Ropetackle one of the South Coast’s most prominent and celebrated arts venues. We believe engagement with the arts is of vital importance to the wellbeing of both individuals and the community, and with such an exciting and eclectic programme ahead of us, we’ll let the events speak for themselves. See you at the bar! THUNKSHOP THURSDAY SUPPERS BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 Our in-house cafe Thunkshop will be serving delicious pre-show suppers from 6pm before most of our Thursday events. Advance With support from booking is recommended but not essential, please contact Sarah on 07957 166092 for further details and to book. Seats are reserved for people dining. Look out for the Thunkshop icon throughout the programme or visit page 58 for the full list of pre-show meals. Programme design by Door 22 Creative www.door22.co.uk @ropetackleart Ropetackle Arts Centre Opera Rock Folk Family Blues Spoken Word Jazz 2 SEPT 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 SEPT 2014 SARA SPADE & THE NOISY BOYS Sara Spade & The Noisy Boys: World War One Centenary Concert She’s back! After a sell-out Ropetackle show in January, Sara Spade & The Noisy Boys return with flapper classics like ‘Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue’ and other popular Charlestons, plus favourite Great War-era songs including Pack up your Troubles in your Old Kit Bag and Long Way to Tipperary. -

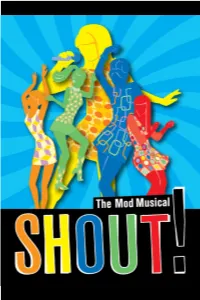

Shout Playbill FINAL.Pdf

Diamond Head Theatre Presents Created by PHILLIP GEORGE & DAVID LOWENSTEIN “Mod Musings” & “Groovy Gab” by PETER CHARLES MORRIS & PHILLIP GEORGE Orchestrations & Additional Arrangements by BRADLEY VIETH Originally Directed Off-Broadway by PHILLIP GEORGE Originally Choreographed Off Broadway by DAVID LOWENSTEIN Originally produced Off-Broadway in New York City by VICTORIA LANG & P.P. PICCOLI and MARK SCHWARTZ Developed in association with Amas Musical Theatre, Donna Trinkoff, Producing Director Directed & Set & Choreographed by Musical Direction by Lighting Design by JOHN RAMPAGE MEGAN ELLIS DAWN OSHIMA Costume Design by Props Design by Sound Design by KAREN G. WOLFE JOHN CUMMINGS III KERRI YONEDA Hair & Make Up Production Stage Manager Assistant To The Design by MATHIAS MAAS Director/Choreographer LINDA LOCKWOOD CELIA CHUN Executive Director Artistic Director DEENA DRAY JOHN RAMPAGE Platinum Sponsors: CRUM & FORSTER FIRST HAWAIIAN BANK JOHN YOUNG FOUNDATION TOYOTA HAWAII Gold Sponsors: AMERICAN SAVINGS BANK C.S. WO & SONS CADES SCHUTTE CITY MILL HAWAII PACIFIC HEALTH FRANCES HISASHIMA MARIKO & JOE LYONS DAVID & NOREEN MULLIKEN CAROLYN BERRY WILSON WAKABAYASHI & BINGHAM FAMILIES SHOUT! THE MOD MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com Diamond Head Theatre • 520 Makapuu Avenue, Honolulu, HI 96816 Phone (808) 733-0277 • Box Office (808) 733-0274 • www.diamondheadtheatre.com Diamond Head Theatre | Shout! w 2 Photographing, -

What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860S-1950S?

Journal of New Zealand Studies What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese? What Best Explains the Discrimination Against the Chinese in New Zealand, 1860s-1950s? MILES FAIRBURN University of Canterbury Dominating the relatively substantial literature on the history of the Chinese in New Zealand is the story of their mistreatment by white New Zealanders from the late 1860s through to the 1950s.1 However, the study of discrimination against the Chinese has now reached something of an impasse, one arising from the strong tendency of researchers in the area to advance their favourite explanations for discrimination without arguing why they prefer these to the alternatives. This practice has led to an increase in the variety of explanations and in the weight of data supporting the explanations, but not to their rigorous appraisal. In consequence, while researchers have told us more and more about which causal factors produced discrimination they have little debated or demonstrated the relative importance of these factors. As there is no reason to believe that all the putative factors are of equal importance, knowledge about the causes is not progressing. The object of this paper is to break the impasse by engaging in a systematic comparative evaluation of the different explanations to determine which one might be considered the best. The best explanation is, of course, not perfect by definition. Moreover, in all likelihood an even better explanation will consist of a combination of that best and one or more of the others. But to find the perfect explanation or a combination of explanations we have to start somewhere. -

Poetry Volume 1.Qxd

The Poems of Frithjof Schuon (1995-1998) The Poems of Frithjof Schuon (1995-1998) Volume 1 Adastra Stella Maris Autumn Leaves The Ring Translated from the German by William Stoddart This is a private edition printed by request only, and is not intended for sale to the general public. © World Wisdom, Inc., all rights reserved. This private edition of the poetry of Frithjof Schuon represents a first translation of the poems written during the last years of his life, as they were created in twenty-three separate volumes. For purposes of economy and space, it comprises the English translation only, without the original German. This translation is the work of William Stoddart, and is largely based on the author's dictated translations, as revised by Catherine Schuon. The order of the books follows the chronology in which they were created, rather than a grouping by collection. www.worldwisdom.com Contents Adastra 9 Stella Maris 81 Autumn Leaves 153 The Ring 237 Notes 306 Index of titles 308 Adastra A Garland of Songs Adastra As an Entry Out of my heart flowed many a song; I sought them not, they were inspired in me — O may the sound of the God-given harp Purify the soul and raise us to Heaven! May the light of wisdom unite With love to accompany our effort; And may our souls find grace: The Path from God to God, eternally. Adastra Ad astra — to the stars — the soul is striving, Called by an unstilled longing. O path of Truth and Beauty that I choose — Of God-remembrance which pervades the soul! Thou art the song that stills all longing — The light of grace; O shine into my heart! The Lord is our Refuge and our Shield — Be thou with Him and He will be with thee. -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

The Folk Singer

THE FOLK SINGER ___________________________ A New Musical Book & Lyrics by Tom Attea Contact: Tom Attea [email protected] (c) 2016 Tom Attea ii. CAST DON, FOLK SINGER & ORGANIZER KIM, HIS GIRLFRIEND TODD, FOLK SINGER AMY, FOLK SINGER ZACK, FOLK SINGER JAN, FOLK SINGER BAND CHORUS AS KIM, FRANK, HARMONY SINGERS AND VIDEOGRAPHERS iii. SONGS WELCOME.............................................................................Don & Others PEOPLE LOOK BEAUTIFUL TO ME................................Amy THE WAR MEMORIAL.......................................................Todd IF ALL YOU WANT IS MORE.............................................Jan THE DAY LINCOLN'S STATUE CAME TO LIFE.............Zack HAMMERED.........................................................................Don TERROR, ERROR..................................................................Todd SITTIN' ON A NUCLEAR BOMB........................................Zack A NEWBORN CHILD............................................................Amy THAT GOOD OLD RAILWAY STATION..........................Don SOUNDS A LOT LIKE LUCK...............................................Zack DO YOU MIND TELLIN' ME WHY?....................................Jan UNDERACHIEVING AS BEST WE CAN............................ Don, Jan, and Amy BLUE COLLAR, CAN'T EARN A DOLLAR.......................Todd I LONG FOR WIDE OPEN SPACES......................................Don WOULD YOU HAVE THE SENSE TO LOVE ME?.............Amy & Zack A CLIMATE OF CHANGE...................................................All -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

Memories of Nick Drake (1969-70)

Counterculture Studies Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 18 2019 Memories of Nick Drake (1969-70) Ross Grainger [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs Recommended Citation Grainger, Ross, Memories of Nick Drake (1969-70), Counterculture Studies, 2(1), 2019, 137-150. doi:10.14453/ccs.v2.i1.17 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Memories of Nick Drake (1969-70) Abstract An account of Australian Ross Grainger's meetings with the British singer songwriter guitarist Nick Drake (1948-74) during the period 1969-70, including discussions at London folk clubs. Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This journal article is available in Counterculture Studies: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ccs/vol2/iss1/18 Memories of Nick Drake (1969-70) Ross Grainger Nick Drake, 29 April 1969. Photograph: Keith Morris. I first met Nick Drake when I arrived in London after attending the Isle of Wight Pop Festival in 1969, which featured as its curtain-closer a very different Bob Dylan to the one I had seen in Sydney in March 1966. However, on thinking about it, Dylan’s more scaled down eclectic country music approach - which he revealed for the first time - kind of prepared me for what I was about to experience in London. The day after I arrived at my temporary London lodgings with friends living in Warwick Avenue, I went to Les Cousins in Greek Street. -

Armandito Y Su Trovason High Energy Cuban Six Piece Latin Band

Dates For Your Diary Folk News Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Dance News Issue 412 CD Reviews November 2009 $3.00 Armandito Y Su Trovason High energy Cuban six piece Latin band ♫ folk music ♫ dance ♫ festivals ♫ reviews ♫ profiles ♫ diary dates ♫ sessions ♫ teachers ♫ opportunities The Folk Federation ONLINE - jam.org.au The CORNSTALK Gazette NOVEMBER 2009 1 AdVErTISINg Rates Size mm Members Non-mem NOVEMBEr 2009 Folk Federation of New South Wales Inc Full page 180x250 $80 $120 In this issue Post Office Box A182 1/2 page 180x125 $40 $70 Dates for your diary p4 Sydney South NSW 1235 ISSN 0818 7339 ABN9411575922 1/4 page 90x60 $25 $50 Festivals, workshops, schools p6 jam.org.au 1/8 page 45 x 30 $15 $35 Folk news p8 The Folk Federation of NSW Inc, formed in Back cover 180x250 $100 $150 Dance news p9 1970, is a Statewide body which aims to present, Folk contacts p10 support, encourage and collect folk m usic, folk 2 + issues per mth $90 $130 dance, folklore and folk activities as they exist Advertising artwork required by 5th of each month. CD Review p14 Advertisements can be produced by Cornstalk if re- in Australia in all their forms. It provides a link quired. Please contact the editor for enquiries about Deadline for December/January Issue for people interested in the folk arts through its advertising Tel: 6493 6758 ADVERTS 5th November affiliations with folk clubs throughout NSW and its Inserts for Cornstalk COPY 10th November counterparts in other States. It bridges all styles [email protected] NOTE: There will be no January issue.