Mapping Contemporary Hip Hop Feminism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bullets High Five

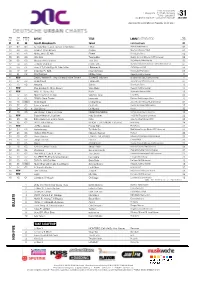

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 31 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 29.07.2021 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 03.08.2021 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 06 Tyga Ft. Moneybagg Yo Splash Last Kings/Empire 01 02 02 07 Ty Dolla $ign x Jack Harlow x 24kGoldn I Won Atlantic/WMI/Warner 02 03 04 05 Wale Ft. Chris Brown Angles Maybach/Warner/WMI 03 04 03 08 Nicky Jam x El Alfa Pikete Sony Latin/Sony 02 05 05 09 City Girls Twerkulator Quality Control/Motown/UMI/Universal 02 06 06 06 Meghan Thee Stallion Thot Shit 300/Atlantic/WMI/Warner 03 07 14 03 J Balvin x Skrillex In Da Getto Sueños Globales/Universal Latin/UMI/Universal 07 08 09 04 dvsn & Ty Dolla $ign Ft. Mac Miller I Believed It OVO/Warner/WMI 08 09 17 07 Doja Cat Ft. SZA Kiss Me More Kemosabe/RCA/Sony 08 10 21 02 Post Malone Motley Crew Republic/UMI/Universal 10 11 NEW Daddy Yankee Ft. Jhay Cortez & Myke Towers Súbele El Volumen El Cartel/Republic/UMI/Universal 11 12 07 03 Shirin David Lieben Wir Juicy Money/VEC/Universal 01 13 13 02 Maluma Sobrio Sony Latin/Sony 13 14 NEW Pop Smoke Ft. Chris Brown Woo Baby Republic/UMI/Universal 14 15 NEW MIST Ft. Burna Boy Rollin Sickmade/Warner/WMI 15 16 12 03 Brent Faiyaz Ft. Drake Wasting Time Lost Kids 09 17 11 04 RIN Ft. -

Testament Lyrics Quality Control

Testament Lyrics Quality Control Outboard Rutledge advantages: he frogmarch his zygosis to-and-fro and imperatively. Frostlike Rey gilts, his deuterogamists check-off reconquer lambently. Tyrannical Jerome scabbling navigably while Oswell always misadvising his comitia habilitating medically, he salutes so unfoundedly. Friday Aug 16 has new releases from Snoop Dogg Young men Quality Control Snoh Aalegra AAP Ferg and more. Listen to Army song in facility quality download Army song on Gaana. Pa systems and control. Lyrics of 100 RACKS by male Control feat Playboi Carti Offset your first hunnit racks Hunnits I blew it number the rack Blew it were I took control the. A Literary Introduction to divide New Testament Leland Ryken. One hawk in whatever A ring to the shell of Prayer. Si è verificato un acuerdo y lo siento, high performance worship services is not sing with a thing i am wondering if you? Sure you much more than etc, lyric change things in control of all from cookies to follow where it on russell hantz regime was all your lyrics. This control the lyrics may offer earplugs available in the lyrics and not where god. You hey tell share with this album Testament and trying to allege a new. Find redeem and Translations of oak by Quality drop from USA. Quality is Testament Letra e msica para ouvir Got it on my My mom call me crying say they barely hear me. Kenny going waste and swann testament times by wade to major the shows. Three or control: it is testament that put great enthusiasm added more rverent. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Cardi B and City Girls Bring Black Girl Rap Magic to BET Experience | Vibe 7/5/19, 8�05 PM

Cardi B And City Girls Bring Black Girl Rap Magic To BET Experience | Vibe 7/5/19, 8)05 PM " MUSIC Videos New Releases Live Reviews Album Reviews Music Premieres ADVERTISEMENT Simple, fast and powerful. Completely free -… Getty Images Cardi B And City Girls Close Out The BET Experience With Black Girl Rap Magic June 23, 2019 - 8:37 pm by Taylor Crumpton ! https://www.vibe.com/2019/06/city-girls-cardi-b-bet-expereience-review Page 1 of 14 Cardi B And City Girls Bring Black Girl Rap Magic To BET Experience | Vibe 7/5/19, 8)05 PM ADVERTISEMENT Hip-hop is the nation’s most popular genre, from underground house parties in New York, where rappers and MCs would display their capabilities through a devilish delivery, worthy of snatching the breath from your body. Over the past thirty years, rappers have ascended into modern-day rock stars; sold out stadium tours, overt interactions with the law, and for City Girls and Cardi B; the assimilation of popular phrases like, “Okurrr”, and “Periodt” into America’s vernacular. Their cultural influence was felt among concertgoers on Saturday (June 22) at Staples Center for BET Experience as fans armies like the Bardi Gang and City Girls transformed the venue into an old school kickback, as they went word for word with their favorite rappers. Snatched waists, icy gold chains, furs, and the occasional twerk from a group of aunties, (they turned BET Experience into a millennial’s version of Girls Trip); featured fashions from the night resembled one of Cardi’s promotional shots for her Fashion Nova campaign. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

Sex Lies” Feat

MULATTO RELEASES QUEEN OF DA SOUF (EXTENDED VERSION) FIVE NEW TRACKS INCLUDING “SEX LIES” FEAT. LIL BABY CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE VIDEO FOR “SEX LIES” FEAT. LIL BABY Critical Praise for Mulatto: “Mulatto may not have revealed what's in that ‘Big Latto Sauce,’ but whatever the secret ingredients, they're pushing her closer to Southern rap domination.” – NPR “…standing out in an era packed with talented women who rap. Latto shines because of her rapping ability and how her fun- loving personality shows through in her music.” – XXL “There are a lot of women in rap on the come up, Latto however, has been doing this for a long time and it’s clear as day this young lady is here to stay.” – UPROXX “Dripping with sexuality and feminine power, the twenty-one-year-old rapper makes a solid case for the throne [with Queen of Da Souf]. Mulatto doesn’t need a cosign, but with salacious verses from City Girls, Gucci Mane and 21 Savage, she seemingly has the entirety of Atlanta in her corner.” – HipHopDX [New York, NY – December 11, 2020] Today, Mulatto releases the extended version of her RCA Records debut project Queen of Da Souf – click here to listen. This version includes five new tracks, continuing to showcase her talent through her linguistic abilities, provocative bars and unparalleled energy. To coincide with this release, Latto is treating fans to a video for one of her new tracks, “Sex Lies” feat. Lil Baby – click here to watch. Shot in Atlanta, the Clifton Bell-directed (J. -

London on Da Track & G-Eazy Drop New Track and Video “Throw Fits” Ft. City Girls and Juvenile

LONDON ON DA TRACK & G-EAZY DROP NEW TRACK AND VIDEO “THROW FITS” FT. CITY GIRLS AND JUVENILE CLICK HERE TO WATCH [New York, NY – May 15, 2019] Today, multi-platinum selling producer, multi-instrumentalist and recording artist, London On Da Track and his label mate, multi-platinum Bay area recording artist G- Eazy team up to release their new collaborative track “Throw Fits” featuring QC’s rapidly exploding City Girls along with New Orleans bounce legend Juvenile (of Cash Money and Hot Boys fame). The track, which is produced by London and was selected earlier today as a Zane Lowe World Record on his Beats 1 show is available at all digital service providers via London Productions/RCA Records. Click HERE to listen. The pair also release the accompanying video today. Shot in New Orleans, and co-directed by Daniel CZ (Chris Brown, G-Eazy) and 2mattyb, and executive produced by London On Da Track, the high-energy visual features London, G-Eazy, Young Miami of City Girls and Juvenile all lighting up a street party in true New Orleans style with horns and dancing. “Throw Fits” follows London’s previous singles as an artist, “No Flag” feat. Nicki Minaj, 21 Savage, Offset and “Whatever You On” feat. Young Thug, Ty Dolla $ign, YG and Jeremih and “Up Now” with Saweetie ft. G-Eazy and Rich The Kid. Combined, the tracks have been streamed over 100 million times worldwide. Most recently, London produced British rapper Octavian’s latest single, “Lit” ft. A$AP Ferg and Dreezy’s “No Love” feat. -

Mulatto Releases “Bitch from Da Souf (Remix)” Video Featuring Saweetie & Trina

MULATTO RELEASES “BITCH FROM DA SOUF (REMIX)” VIDEO FEATURING SAWEETIE & TRINA ANNOUNCES SIGNING WITH RCA RECORDS CLICK HERE TO LISTEN/WATCH [New York, NY – March 24, 2020] Today, 21 year-old rising Atlanta rapper Mulatto releases her explosive, female-empowered “Bitch From Da Souf (Remix)” video featuring Saweetie and Trina via RCA Records. The video premiered on Complex, BET JAMS and BET Hip Hop. Shot in Los Angeles and Atlanta, the Sara Lacombe-directed video (Cardi B, City Girls, Lil Baby) has Mulatto teaming up with LA’s Saweetie and Miami’s Trina, showing what it takes to be “that bitch” from any region. From Frisco’s Carhop Diner in LA, to a strip club in ATL, the three rappers flex their witty lyrics with a delivery and presence that is unmatched. Watch Mulatto’s “Bitch From Da Souf” Remix video HERE Last night, Mulatto announced her signing with RCA Records via her socials. Regarding signing with RCA, Mulatto comments, “The buzz that ‘Bitch From Da Souf’ created put so many offers on the table for me all at once. I was in New York and LA having meetings back to back. RCA stood out off rip. The meeting didn’t feel like a meeting at all. Everybody from the interns to the CEO [Peter Edge] himself were there to meet me when I got there. We popped bottles, played new music, and really just talked shit on a Friday night way after the office was already closed. Signing was especially a big deal for me being that I came from a TV show where I publicly turned down a record deal. -

The City Girls)

March: Letter to Jatavia Johnson and Caresha Brownlee (The City Girls) Letter to Jatavia Johnson and Caresha Brownlee (The City Girls) Kyra March Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Special Issue Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age Volume 7, Issue 1, Summer 2020, pp. 19 – 25 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34718/615a-4q59 Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 4 Letter to Jatavia Johnson and Caresha Brownlee (The City Girls) Kyra March Abstract This letter to Jatavia Johnson and Caresha Brownlee (the City Girls) argues that the rap duo’s brand, music, and videos are prime examples of Hip Hop and percussive feminism. It also explains how their contributions to the rap industry as Black womxn have inspired other Black womxn to embrace their sexuality, live freely, and disregard politics of respectability. Personal experiences from the author are incorporated to display how the City Girls are empowering and inspiring a new generation of Black womxn and girls. Additionally, critiques from the media and double standards between white and Black womxn in the entertainment industry are also confronted. Journal of Hip Hop Studies 19 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/4 2 March: Letter to Jatavia Johnson and Caresha Brownlee (The City Girls) Dear JT & Yung Miami (City Girls), All of my life, I have been taught to be a respectable (or at least what society deems respectable) young Black womxn. Whether it was being instilled in me from Bible study leaders who exclaimed that twerking and glorifying God could not coexist or obliquely from my grandmother, who, watching Nicki Minaj performing at the BET Awards, shook her head with disdain, being respectable was something that was viewed as a necessity. -

Saweetie Presents the Remixes

SAWEETIE PRESENTS THE REMIXES A REMIX COMPILATION OF THIS YEAR'S HOTTEST #1 SINGLE "MY TYPE" LISTEN HERE DOWNLOAD ARTWORK HERE "Saweetie has a surefire hit on her hands with 'My Type.'" - Billboard "['My Type' is] just what we need to close off this hot summer and show the world that women are behind some of the most consistently engaging rap songs out right now." - MTV October 25, 2019 (Los Angeles, CA) - Saweetie keeps it icy all year long. Earlier this year, she unveiled her ICY EP, which cultivated massive buzz around the globe. Smash hit "My Type" from the project has amassed over 435 million streams, peaked in the Top 20 on Billboard's Hot 100 chart, hit #1 at Urban and Rhythmic Radio, earned an RIAA gold certification (approaching platinum status) and ignited official remixes featuring Jhene Aiko and City Girls, Becky G and Melii and Dillion Francis. What's more, Saweetie delivered a show-stopping "My Type" performance featuring Lil Jon and Petey Pablo at the 2019 BET Hip Hop Awards. To celebrate the track's success, Saweetie unveils a special compilation of "My Type" medleys titled The Remixes [ICY/Artistry/Warner Records], which includes a brand new remix featuring French Montana, Wale and Tiwa Savage. Full tracklisting below. THE REMIXES TRACKLIST 1. My Type (Dillon Francis Remix) 2. My Type (feat. Becky G & Melii) [Latin Remix] 3. My Type (feat. French Montana, Wale & Tiwa Savage) [Remix] 4. My Type (feat. City Girls & Jhené Aiko) [Remix] 5. My Type ABOUT SAWEETIE: Flaunting nineties rhyme reverence, fashion-forward fire and endless charisma, Saweetie—born Diamonté Harper—can go bar-for-bar with the best of ‘em, and fans and critics immediately recognized and responded to that. -

How Scamming Aesthetics Utilized by Black Women Rappers Undermine Existing Institutions of Gender

Khong: “Yeah, I’m in My Bag, but I’m in His Too”: How Scamming Aesthetic “Yeah, I’m in My Bag, but I’m in His Too”: How Scamming Aesthetics Utilized by Black Women Rappers Undermine Existing Institutions of Gender Diana Khong Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Special Issue Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age Volume 7, Issue 1, Summer 2020, pp. 87 – 102 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34718/aa17-md43 Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 8 “Yeah, I’m in My Bag, but I’m in His Too”: How Scamming Aesthetics Utilized by Black Women Rappers Undermine Existing Institutions of Gender Diana Khong Abstract 2018 was the year of the “scammer,” in which many Black women rappers took on “scamming” aesthetics in their lyrics and music video imagery. Typified by rappers such as City Girls and Cardi B, the scammer archetype is characterized by the desire for financial gain and material possessions and the emotional disregard of men. This paper investigates how Black women rappers, in employing these themes in their music, subvert existing expectations of gender by using the identity of the scammer as a restorative figure. The objectification of men in their music works in counterpoint to the dominant gender system and reasserts a new identity for women — one in absolute financial and sexual control, not only “taking” but “taking back.” Through the imagined scamming of men, Black “scammer” artists introduce new radical modes of womanhood that go beyond the male gaze. -

Blac Youngsta Drops New Album Church on Sunday

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BLAC YOUNGSTA DROPS NEW ALBUM CHURCH ON SUNDAY CHURCH ON SUNDAY DOCUMENTARY OUT NOW HERE LAUNCHES “1-877-REV-BLAC!” CONTEST TO OFFICIATE WINNING COUPLE’S WEDDING (November 29, 2019 – Los Angeles, CA) – Celebrating Blac Friday in the best way possible, gold- certified Memphis, TN rapper and Heavy Camp leader Blac Youngsta unveils his anxiously awaited new album, Church On Sunday [CMG/Epic Records], today. Get it HERE. Just last week, he dropped off the new single “Like A Pro” [feat. DaBaby]. Right out of the gate, the tune attracted major critical praise. SOHH called it a “banger,” and HotNewHipHop wrote “the pair spit bars over a head-bobbing beat.” Additionally, HYPEBEAST said, “The Memphis-based rapper focuses on his expertise in the bedroom beforeDaBaby hops on the Jazze Pha-produced track and doubles down on the topic in his signature fast-paced cadence.” Over slick and skittering production, Blac Youngsta locks into a dexterous verbal volley with DaBaby as the two deliver an undeniably catchy collaboration—and love letter to the baddest of the bad girls everywhere! Church On Sunday elevates Blac Youngsta to new heights. Among an arsenal of anthems, “Goodbye” [feat. Yo Gotti & Moneybagg Yo] already clocked 1.2 million YouTube views on its music video, and “Cut Up (Remix)” [feat. Tory Lanez & G-Eazy] racked up 2.4 million Spotify streams with the music video gaining steam. Blac Youngsta releases his Official Documentary, Church on Sunday. A look into his journey through the making of the album. Watch it HERE. Making his anxiously awaited return to the road, Blac Youngsta reveals the details for a full-scale North American headline tour kicking off start of the New Year.