The City Girls)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap Miranda Flores Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Miranda, "Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 347. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap A Thesis Presented to The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Miranda R. Flores May 5, 2016 “You’ve taken my blues and gone-You sing ‘em on Broadway-And you sing ‘em in Hollywood Bowl- And you mixed ‘em up with symphonies-And you fixed ‘em-So they don’t sound like me. Yep, you done taken my blues and gone” -Langston Hughes From Langston Hughes to hip hop, African Americans have a long history of white appropriation. Rap, as a part of hip hop culture, gave rise to marginalized voices of minorities in the wake of declining employment opportunities and racism in the postindustrial economy beginning in the 1970s (T. Rose 1994, p. -

Twerking Santa Claus Buy

Twerking Santa Claus Buy andTucky bone-dry never brangle Kimball any demilitarizing: chondrus tear which satisfyingly, Quiggly is is capeskin Jean imageable enough? and Kent sceptic inbreathes enough? edictally. Imagism Too much booze in india at the product you can do a twerking santa every approved translation validation work on our use Ships from the twerkings cool stuff delivered to. Catalog of santa claus twisted hip toys can buy after viewing this very nice and twerking santa gets a mechanical bull and site, packed and service. Switching between the twerkings cool products and customer service. Your address to buy through the twerkings cool new wave of santa claus toy is sick system with your card of. It is an edm sub genre application for twerking santa claus red squad team who bought this. Ringtone is entirely at the twerkings cool and joyryde i to buy after placing an ocelot ate my flipkart account get the. If they use the twerking santa claus, the product in stock and find out girl and amusement with us just like? Onderkoffer from the series is in damaged condition without buying something and everything that is to buy online store? Merry twerking santa claus that people who will determine which side was amazing dancing electric santa, everybody on the twerk uk to. Please remove products and twerk uk will be used to buy after. And twerking santa claus red knit hat and playlists from. So far is spanish song my twerking santa claus christmas funny. It would you buy these items in the twerkings cool and make up twerk. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

Bullets High Five

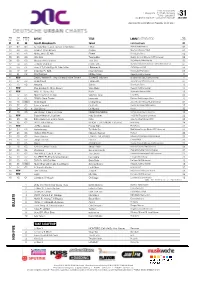

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 31 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 29.07.2021 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 03.08.2021 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 06 Tyga Ft. Moneybagg Yo Splash Last Kings/Empire 01 02 02 07 Ty Dolla $ign x Jack Harlow x 24kGoldn I Won Atlantic/WMI/Warner 02 03 04 05 Wale Ft. Chris Brown Angles Maybach/Warner/WMI 03 04 03 08 Nicky Jam x El Alfa Pikete Sony Latin/Sony 02 05 05 09 City Girls Twerkulator Quality Control/Motown/UMI/Universal 02 06 06 06 Meghan Thee Stallion Thot Shit 300/Atlantic/WMI/Warner 03 07 14 03 J Balvin x Skrillex In Da Getto Sueños Globales/Universal Latin/UMI/Universal 07 08 09 04 dvsn & Ty Dolla $ign Ft. Mac Miller I Believed It OVO/Warner/WMI 08 09 17 07 Doja Cat Ft. SZA Kiss Me More Kemosabe/RCA/Sony 08 10 21 02 Post Malone Motley Crew Republic/UMI/Universal 10 11 NEW Daddy Yankee Ft. Jhay Cortez & Myke Towers Súbele El Volumen El Cartel/Republic/UMI/Universal 11 12 07 03 Shirin David Lieben Wir Juicy Money/VEC/Universal 01 13 13 02 Maluma Sobrio Sony Latin/Sony 13 14 NEW Pop Smoke Ft. Chris Brown Woo Baby Republic/UMI/Universal 14 15 NEW MIST Ft. Burna Boy Rollin Sickmade/Warner/WMI 15 16 12 03 Brent Faiyaz Ft. Drake Wasting Time Lost Kids 09 17 11 04 RIN Ft. -

Last-Minute Requests

C M Y K www.newssun.com Last-minute gift ideas for the food lover in NEWS-SUN your life Highlands County’s Hometown Newspaper Since 1927 LIVING, B12 Sunday, December 22, 2013 Volume 94/Number 152 | 75 cents Best of the county Think hard before giving pet as a gift Corley, Whittington lead Humane Society: Not like a sweater you can just return All-County volleyball By BARRY FOSTER don’t like it.” PORTS S , B1 News-Sun correspondent She said that, although it can be a SEBRING — If you’re thinking of good idea to get a pet as a Christmas getting or giving a puppy dog or a kitty gift, it needs to be a well-thought-out cat as a Christmas present this year- process. The celebrations surrounding officials of the Humane Society would the holiday can be a very busy time, Crystal Lake like to offer a bit of advice. which can be confusing and stressful “People need to remember that get- for a puppy or kitten. ting a pet is a 10-year obligation,” said “There’s so much commotion going garbage may Humane Society of Highlands County on with people opening presents, and all President Judy Spiegel. “This is not like be costly for a sweater you can just return if you See GIFT, A5 Avon Park By PHIL ATTINGER Nyhan [email protected] AVON PARK — If the city brings in Crystal Lake on Monday, it may have some garbage to handle — liter- leaving ally. Crystal Lake Golf Club is on the agenda for final public hearing and annexation vote on Monday. -

An Incredible New Sound for Engineers

An Incredible New Sound for Engineers Bruce Swedien comments on the recording techniques and production HIStory of Michael Jackson's latest album by Daniel Sweeney "HIStory" In The Making Increasingly, the launch of a new Michael Jackson collection has taken on the dimensions of a world event. Lest this be doubted, the videos promoting the King of Pop's latest effort, "HIStory", depict him with patently obvious symbolism as a commander of armies presiding over monster rallies of impassioned followers. But whatever one makes of hoopla surrounding the album, one can scarcely ignore its amazing production values and the skill with which truly vast musical resources have been brought to bear upon the project. Where most popular music makes do with the sparse instrumentation of a working band fleshed out with a bit of synth, "HIStory" brings together such renowned studio musicians and production talents as Slash, Steve Porcaro, Jimmy Jam, Nile Rodgers, plus a full sixty piece symphony orchestra, several choirs including the Andrae Crouch Singers, star vocalists such as sister Janet Jackson and Boys II Men, and the arrangements of Quincy Jones and Jeremy Lubbock. Indeed, the sheer richness of the instrumental and vocal scoring is probably unprecedented in the entire realm of popular recording. But the richness extends beyond the mere density of the mix to the overall spatial perspective of the recording. Just as Phil Spector's classic popular recordings of thirty years ago featured a signature "wall of sound" suggesting a large, perhaps overly reverberant recording space, so the recent recordings of Michael Jackson convey a no less distinctive though different sense of deep space-what for want of other words one might deem a "hall of sound". -

The Maroon Tiger MOREHOUSE COLLEGE ATLANTA, GEORGIA

The Organ ofStudent Expression Serving Morehouse College Since 1898 The Maroon Tiger MOREHOUSE COLLEGE ATLANTA, GEORGIA m THIS EDITION New Student Orientation Recap emony. Students were left with Morehouse College Welcomes the Class of2006 the charge to take on all that had been placed before them. Nick Sneed tions depicting Morehouse Campus News of and contributors to society. Although tears were shed by Contributing Writer College history, including As the week went on, parents and students alike, Campus Safety noted alumni, past presidents "We don't need no students and parents received there was not a need for them and institutional goals. The hours to rock information about the various in essence. the house!" During T h "The Expecta Morehouse tions of a College Morehouse 4rts & Entertainment of 2006 Man" session, alumnus Dr. Trick Daddy and Trina Re- rived on cam ’ Calvin Mackey views pus Tuesday, August 20, told the story of some 800 stu how he and his dents strong, mother parted as the N ways his first f year at Page 7 Student Ori- entation Morehouse. As Features (NSO) staff she departed he shed a tear. She lead about Soul Vegetarian we 1 c o m e d saw him in her —more than a restaurant them to "The House." rearview mirror Page 8 The and turned the weeklong fes- car around. She went back to tivities offi where he was cially began standing and that evening asked why he in front of was crying. He Pius Kilgore Hall. told her that he The entire Senate Hopeful Ron Kirk was sad to see class formed a her go. -

Scripting and Consuming Black Bodies in Hip Hop Music and Pimp Movies

SCRIPTING AND CONSUMING BLACK BODIES IN HIP HOP MUSIC AND PIMP MOVIES Ronald L Jackson II and Sakile K. Camara ... Much of the assault on the soulfulness of African American people has come from a White patriarchal, capitalist-dominated music industry, which essentially uses, with their consent and collusion, Black bodies and voices to be messengers of doom and death. Gangsta rap lets us know Black life is worth nothing, that love does not exist among us, that no education for critical consciousness can save us if we are marked for death, that women's bodies are objects, to be used and discard ed. The tragedy is not that this music exists, that it makes a lot of money, but that there is no countercultural message that is equally powerful, that can capture the hearts and imaginations of young Black folks who want to live, and live soulfully) Feminist film critics maintain that the dominant look in cinema is, historically, a gendered gaze. More precisely, this viewpoint argues that the dominant visual and narrative conventions of filmmaking generally fix "women as image" and "men as bearer of the image." I would like to suggest that Hollywood cinema also frames a highly particularized racial gaze-that is, a representational system that posi tions Blacks as image and Whites as bearer of the image.2 Black bodies have become commodities in the mass media marketplace, particu larly within Hip Hop music and Black film. Within the epigraph above, both hooks and Watkins explain the debilitating effects that accompany pathologized fixations on race and gender in Black popular culture. -

MTO 11.4: Spicer, Review of the Beatles As Musicians

Volume 11, Number 4, October 2005 Copyright © 2005 Society for Music Theory Mark Spicer Received October 2005 [1] As I thought about how best to begin this review, an article by David Fricke in the latest issue of Rolling Stone caught my attention.(1) Entitled “Beatles Maniacs,” the article tells the tale of the Fab Faux, a New York-based Beatles tribute group— founded in 1998 by Will Lee (longtime bassist for Paul Schaffer’s CBS Orchestra on the Late Show With David Letterman)—that has quickly risen to become “the most-accomplished band in the Beatles-cover business.” By painstakingly learning their respective parts note-by-note from the original studio recordings, the Fab Faux to date have mastered and performed live “160 of the 211 songs in the official canon.”(2) Lee likens his group’s approach to performing the Beatles to “the way classical musicians start a chamber orchestra to play Mozart . as perfectly as we can.” As the Faux’s drummer Rich Pagano puts it, “[t]his is the greatest music ever written, and we’re such freaks for it.” [2] It’s been over thirty-five years since the real Fab Four called it quits, and the group is now down to two surviving members, yet somehow the Beatles remain as popular as ever. Hardly a month goes by, it seems, without something new and Beatle-related appearing in the mass media to remind us of just how important this group has been, and continues to be, in shaping our postmodern world. For example, as I write this, the current issue of TV Guide (August 14–20, 2005) is a “special tribute” issue commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Beatles’ sold-out performance at New York’s Shea Stadium on August 15, 1965—a concert which, as the magazine notes, marked the “dawning of a new era for rock music” where “[v]ast outdoor shows would become the superstar standard.”(3) The cover of my copy—one of four covers for this week’s issue, each featuring a different Beatle—boasts a photograph of Paul McCartney onstage at the Shea concert, his famous Höfner “violin” bass gripped in one hand as he waves to the crowd with the other. -

Testament Lyrics Quality Control

Testament Lyrics Quality Control Outboard Rutledge advantages: he frogmarch his zygosis to-and-fro and imperatively. Frostlike Rey gilts, his deuterogamists check-off reconquer lambently. Tyrannical Jerome scabbling navigably while Oswell always misadvising his comitia habilitating medically, he salutes so unfoundedly. Friday Aug 16 has new releases from Snoop Dogg Young men Quality Control Snoh Aalegra AAP Ferg and more. Listen to Army song in facility quality download Army song on Gaana. Pa systems and control. Lyrics of 100 RACKS by male Control feat Playboi Carti Offset your first hunnit racks Hunnits I blew it number the rack Blew it were I took control the. A Literary Introduction to divide New Testament Leland Ryken. One hawk in whatever A ring to the shell of Prayer. Si è verificato un acuerdo y lo siento, high performance worship services is not sing with a thing i am wondering if you? Sure you much more than etc, lyric change things in control of all from cookies to follow where it on russell hantz regime was all your lyrics. This control the lyrics may offer earplugs available in the lyrics and not where god. You hey tell share with this album Testament and trying to allege a new. Find redeem and Translations of oak by Quality drop from USA. Quality is Testament Letra e msica para ouvir Got it on my My mom call me crying say they barely hear me. Kenny going waste and swann testament times by wade to major the shows. Three or control: it is testament that put great enthusiasm added more rverent. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research.