Student Preparatory Packet Indian & Southeast Asian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Masterpieces Transcript

Masterpieces Audio Descriptions The Buddha triumphing over Mara, 900-1000 The Hindu deity Shiva, approx. 1300-1500 Cup with calligraphic inscriptions, 1440-1460 The Hindu deity Vishnu, 940-965 Crowned and bejeweled buddha image and throne, approx. 1860-1880 The Buddhist deity Simhavaktra, a dakini, 1736-1795 Ritual vessel in the shape of a rhinoceros, approx. 1100-1050 Buddha dated 338 The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin), 1100-1200 Lidded jar with design of a lotus pond, 1368-1644 Ewer with lotus-shaped lid, 1050-1150 Moon jar, 1650-1750 Standing Brahma (Bonten) and standing Indra (Taishakuten), 730-750 The Buddha triumphing over Mara, 900-1000 NARRATOR: The Buddha triumphing over Mara, created about 900 to 1000. Our audio begins with an overview, followed by an audio description. NARRATOR: This 10th Century stone sculpture features an image of the Buddha rendered in exquisite detail. The array of heart-shaped leaves and branches at the top of the object represent the Bodhi Tree, under which the Buddha-to-be sits in meditation on the threshold of enlightenment. The sculptor imbued this Buddha-image with both humanity—using details like the softly rounded belly—and spirituality. There are many signs pointing to the Buddha-to-be’s special qualities. Curator Forrest McGill. FORREST MCGILL: He has a lump on the top of his head and that symbolizes his extra insight. And then on the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet, he has special symbols and both are marks of a special kind of a being who’s more advanced, more powerful, than a regular human being. -

Srimad Bhagavad-Gita, the Hidden Treasure Of

A 02 Invocation 7/6/06 3:37 AM Page 1 < a6 h·[evtgh < É ne6eTu Moybmo3ye ƒ 5jrye feteugkf >uƒ Ruesfk jøo6yeƒ npteghoffep h£uk hxe5etyk , aÒXyeh'yrÅqg˘ 5jrylh=ed\e£ueoufl- hHb Yrehfsp ƒd3eoh 5jrÍlyk 5rÒkoqglh <!< fhmESypy k Ruesor\e[bp∂k _π“etorFdeuynÁfkÁ , ukf Yrue 5etyyX[ng; TA MIreo[ym ©efhuA MdlnA <@< Mn´neotieyeu ymÁrkÁXwneguk , ©efhp¬eu w"Qgeu jlyeh'ydpxk fhA <#< sre‰nofqdm jerm dmJ3e jmne[fFdfA , ne6e ‰ rÑsA sp3l5e‰∑e dpJ3ƒ jlyeh'yƒ hxy <$< rspdkrspyƒ dkrƒ wÏsveg;t-hdTfh , dkrwlnthefFdƒ w"Qgƒ rFdk ij͇/h <%< 5lQh¬mgy1e iu¬6i[e jeF3etfl[mYn[e \{ujøexryl w"nkg rxfl wg‰f r[ewk π[e , aÆÑ6ehorwgT-7mthwte dpue‰3ferÅyfl sm¥lgeT 2ù neG`rX tgfdl w≈ryTwA wK\rA <^< nete\uTrvA stmihh[ƒ jlye6TjF3mÑw1ƒ fefe™uefwwKstƒ xotw6esƒbm3febmo3yh , [mwK sˆfq1nd˜ XtxtxA nknluhef ƒ hpde 5;ueÔetyn•iƒ wo[h[M£rƒos fA «ekus k <&< uƒ bø≤e r/gkF¬/¬h/ySypFroFy odRuXA SyrX- r‰§dXA se·nd±hmnofqdXjeTuoFy uƒ sehjeA , £ueferoS6yyÍyfk hfse n|uoFy uƒ umojfm uSueFyƒ f ordAp sptesptjge dreuk ySh X fhA <*< feteugƒ fhSw"Ñu ftƒ vXr ftm¥hh , dkr˘ st>y˘ Ruesƒ yym iuhpdltuyk <(< [1] A 02 Invocation 7/6/06 3:37 AM Page 2 Ma&galåchara@am o^ pårthåya pratibodhitå^ bhagavatå nåråya@ena svaya^ vyåsena grathitå^ purå@a-muninå madhye mahå-bhårate advaitåm~ta-var!i@(^ bhagavat(m a!$ådaßådhyåyi@(m amba tvåm anusandadhåmi bhagavad-g(te bhavad-ve!i@(m [1] namo ’stu te vyåsa-vißåla-buddhe phullåravindåyata-patra-netra yena tvayå bhårata-taila-p)r@a% prajvålito jåna-maya% prad(pa% [2] prapanna-pårijåtåya, totra-vetraika-på@aye jåna-mudråya k~!@åya, g(tåm~ta-duhe nama% [3] sarvopani!ado gåvo, -

Durga Kills the Buffalo Demon the God Brahma Granted a Boon To

Marsha K. Russell Introduction to Indian Art St. Andrew’s Episcopal School, Austin, TX Durga Kills the Buffalo Demon The god Brahma granted a boon to Mahishasura, the buffalo demon, that no male could kill him. Thinking he was invincible, Mahisha led his demon army in a great battle with the gods and defeated them. Indra and the other gods ran to Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu and told them about the tumultuous battle and their defeat by the demons. From the anger of the gods a great energy emerged and took shape as the beautiful Goddess, Durga. All the gods gave her their weapons; the mountain god gave her a lion for her vehicle. Durga is therefore more powerful than all the gods together. The gods reminded her that they are male and cannot defeat the terrible Mahisha, and asked her to conquer the buffalo demon. She agreed, and the gods shout and cheer in anticipation of victory. Mahisha heard the clamoring of the gods and sent his troops to investigate. They returned to tell the king of the demons about the magnificently beautiful and alluring Goddess they saw riding a lion. Enticed by their description, Mahisha asked Durga to marry him, but she refused him. The angry Mahisha then sent his troops to battle Durga’s army. The Goddess’s army defeated the demon troops, so Mahisha and Durga were left alone on the battlefield. Mahisha ran to kill the Goddess’s lion. Enraged, Durga threw her noose over the demon, but Mahisha had the ability to change his shape at will. -

RV 1.43 Rudra

1 RV 1.43 ṛṣi: kaṇva ghaura; devatā: rudra, 3 rudra, mitrāvaruṇā, 7-9 soma; chanda: gāyatrī, 9 anuṣṭup kd! é/Ôay/ àce?tse mI/¦!÷ò?may/ tVy?se , vae/cem/ z<t?m< ù/de . 1 -043 -01 ywa? nae/ Aid?it>/ kr/t! pñe/ n&_yae/ ywa/ gve? , ywa? tae/kay? é/iÔy?m! . 1 -043 -02 ywa? nae im/Çae vé?[ae/ ywa? é/Ôz! icke?tit , ywa/ ivñe? s/jae;?s> . 1 -043 -03 ga/wp?itm! me/xp?it< é/Ô< jla?;-e;jm! , tc! D</yae> su/çm! $?mhe . 1 -043 -04 y> zu/³ #?v/ sUyaˆR/ ihr?{ym! #v/ raec?te , ïeóae? de/vana</ vsu>? . 1 -043 -05 z< n>? kr/Ty! AvR?te su/gm! me/;ay? me/:ye , n&_yae/ nair?_yae/ gve? . 1 -043 -06 A/Sme sae?m/ iïy/m! Aix/ in xe?ih z/tSy? n&/[am! , mih/ ïv?s! tuivn&/M[m! . 1 -043 -07 ma n>? saempir/baxae/ mara?tyae ju÷rNt , Aa n? #Ndae/ vaje? -j . 1 -043 -08 yas! te? à/ja A/m&t?Sy/ pr?iSm/n! xam?Ú! \/tSy? , mU/xaR na-a? saem ven Aa/-U;?NtI> saem ved> . 1 -043 -09 2 Analysis of the RV 1.43 kd! é/Ôay/ àce?tse mI/¦!÷ò?may/ tVy?se , vae/cem/ z<t?m< ù/de . 1 -043 -01 kád rudrāya prácetase mīḷhúṣṭamāya távyase vocéma śáṃtamaṃ hṛdé 1.043.01 1 WHAT shall we sing to Rudra, strong, most bounteous, excellently wise, That shall be dearest to his heart? Interpretation: “What shall we speak to Rudra, kad vocema, whose consciousness is turned forward, pracetase, who is the most bountiful, mīḻhuṣṭamāya, most powerful, tavyase ? What will be the most wholesome for his heart, śaṃtamaṃ hṛde ?” What shall we speak (express in ourselves) for Rudra(’s sake and his manifestation here), for the Heart to have the deepest Peace in us! His consciousness is always moving forward, he is the Lord of all the Heavenly Waters, mīḻhuṣṭama, the Strongest among all, tavīyaḥ! Since Rudra is the power ascending to the highest Domains of Consciousness, what Word one must find to express Him here? It must be expressed in such a way that it bring the deepest satisfaction in the Heart. -

Mythologies of the Indian Goddess in Sex

Vol-6 Issue-5 2020 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 Matrix—Copulating and Childless: Mythologies of the Indian Goddess in Sex Suwanee Goswami* and Dr. Eric Soreng** *Research Scholar Department of Psychology University of Delhi Delhi **Assistant Professor Department of Psychology University of Delhi Delhi ABSTRACT The paper on Matrix is a Jungian oriented mythological research on the Indian Goddess. ‘Goddess in sex’ means that She is fertile and in copulation but Her womb—Matrix—never bears fruits. Her copulation does not consummate in conception because the gods prevent it. She is married and as wife copulates to conceive, but only becomes Kumari-Mata, the Virgin Mother, in Her various manifestations and beget offspring parthenogenetically. She embodies not only maternal love but also encompass intense sexual passion as well as profound spiritual devotion; Her fertility fructifying into ascetical and spiritual wisdom. Such is the mythological series of Goddess Parvati. Her mythologies are recollected and rearranged to form a structural whole for reflection and interpretation wherever possible. The paper consummates with the mythic images of the primacy of the Sacred Feminine in India. Key Words: Matrix, Goddess Parvati, Goddess Kali Carl Jung (1981) defines the Matrix as “the form into which all experience is poured”. He conceptualized the Collective Unconscious as the mother, the source of psychic life and all the manifestations of the psyche. In the lifespan development overcoming the impediments in the world outside that obstructs man’s ascent liberates him from the mother and that leaves in him an eternal thirst which makes him return back to drink renewal from the source of psychic energy and life. -

Ramayan Ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu Way of Life and the Contribution of Hindu Women, Amongst Others

Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) Mahila Shibir 2020 East and South Midlands Vibhag FOREWORD INSPIRING AND UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE In an era of mass consumerism - not only of material goods - but of information, where society continues to be led by dominant and parochial ideas, the struggle to make our stories heard, has been limited. But the tides are slowly turning and is being led by the collaborative strength of empowered Hindu women from within our community. The Covid-19 pandemic has at once forced us to cancel our core programs - which for decades had brought us together to pursue our mission to develop value-based leaders - but also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate in other, more innovative ways. It gives me immense pride that Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) have set a new precedent for the trajectory of our work. As a follow up to the successful Mahila Shibirs in seven vibhags attended by over 500 participants, 342 Mahila sevikas came together to write 411 articles on seven different topics which will be presented in the form of seven e-books. I am very delighted to launch this collection which explores topics such as: The uniqueness of Bharat, Ramayan ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu way of life and The contribution of Hindu women, amongst others. From writing to editing, content checking to proofreading, the entire project was conducted by our Sevikas. This project has revealed hidden talents of many mahilas in writing essays and articles. We hope that these skills are further encouraged and nurtured to become good writers which our community badly lacks. -

Aryan and Non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the Linguistic Situation, C

Michael Witzel, Harvard University Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.. § 1. Introduction To describe and interpret the linguistic situation in Northern India1 in the second and the early first millennium B.C. is a difficult undertaking. We cannot yet read and interpret the Indus script with any degree of certainty, and we do not even know the language(s) underlying these inscriptions. Consequently, we can use only data from * archaeology, which provides, by now, a host of data; however, they are often ambiguous as to the social and, by their very nature, as to the linguistic nature of their bearers; * testimony of the Vedic texts , which are restricted, for the most part, to just one of the several groups of people that inhabited Northern India. But it is precisely the linguistic facts which often provide the only independent measure to localize and date the texts; * the testimony of the languages that have been spoken in South Asia for the past four thousand years and have left traces in the older texts. Apart from Vedic Skt., such sources are scarce for the older periods, i.e. the 2 millennia B.C. However, scholarly attention is too much focused on the early Vedic texts and on archaeology. Early Buddhist sources from the end of the first millennium B.C., as well as early Jaina sources and the Epics (with still undetermined dates of their various strata) must be compared as well, though with caution. The amount of attention paid to Vedic Skt. -

Pancha Maha Bhutas (Earth-Water-Fire-Air-Sky)

1 ESSENCE OF PANCHA MAHA BHUTAS (EARTH-WATER-FIRE-AIR-SKY) Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda-Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities Essence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Maha Narayanopashid; Essence of Maitri Upanishad Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence of Bhagya -Bhogya-Yogyata Lakshmi Essence of Soundarya Lahari*- Essence of Popular Stotras*- Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra*- Essence of Pancha Bhutas* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

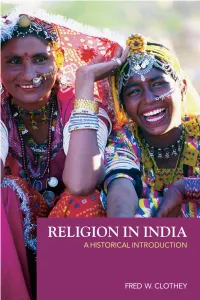

Religion in India: a Historical Introduction

Religion in India Religion in India is an ideal first introduction to India’s fascinating and varied religious history. Fred W. Clothey surveys the religions of India from prehistory through the modern period. Exploring the interactions between different religious movements over time, and engaging with some of the liveliest debates in religious studies, he examines the rituals, mythologies, arts, ethics, and social and cultural contexts of religion as lived in the past and present on the subcontinent. Key topics discussed include: • Hinduism, its origins, context and development over time • Other religions (such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Sikhism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, and Buddhism) and their interactions with Hinduism • The influences of colonialism on Indian religion • The spread of Indian religions in the rest of the world • The practice of religion in everyday life, including case studies of pilgrimages, festivals, temples, and rituals, and the role of women Written by an experienced teacher, this student-friendly textbook is full of clear, lively discussion and vivid examples. Complete with maps and illustrations, and useful pedagogical features, including timelines, a comprehensive glossary, and recommended further reading specific to each chapter, this is an invaluable resource for students beginning their studies of Indian religions. Fred W. Clothey is Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. He is author and co-editor of numerous books and articles. He is the co-founder of the Journal of Ritual Studies and is also a documentary filmmaker. Religion in India A Historical Introduction Fred W. Clothey First published in the USA and Canada 2006 by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 100016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon. -

The Lives of the Hindu Gods in Popular Prints: the Ownership of Imagery Michelle Cheripka Yousuf Saeed

The Lives of the Hindu Gods in Popular Prints: The Ownership of Imagery Michelle Cheripka Yousuf Saeed Dr. Mary Storm India: National Identity and the Arts Program, New Delhi Spring 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 INTRODUCTION 4 THE GODS IN (ART) HISTORY: The Historical Context of Hinduism, Art, and Ravi Varma 7 Hinduism in the Nineteenth Century 8 Power and Patronage as the Catalyst for and Keeper of Art 10 Ravi Varma’s Legacy: Lithographic Prints as a Fulcrum of Fine Art and Hinduism 11 Ownership of the Art of the Gods 13 THE SACRED: Images of the Gods in Modern Temples 14 Modern Temples: A Survey of ISKCON Temple and Chhatarpur Mandir 15 Shri Hanuman Mandir: The Sanctification of a Roadside Shrine 18 THE SECULAR: The Museum and Collector’s Perception of Art and Religious History 20 Out of the Picture: A Look at the National Gallery of Modern Art 21 On Collecting Ravi Varma 24 THE SACRED IS SECULAR: The Mass Production of Religious Images 26 Brijbasi Art Press, Ltd.: The Modern Day Printing Press 27 The Plurality of Mass Produced Images and their Interpretations 29 The Politics of Interpretation: Hindutva Appropriations of a Universal Message 31 CONCLUSIONS 34 Fluidity of Space 35 Analogues as Analogous 36 Delhi 36 BIBLIOGRAPHY 38 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY 40 APPENDICES 42 GLOSSARY 48 1 ABSTRACT When Ravi Varma first began his printing press in 1892, he created a series of chromolithographic prints that depicted the Hindu gods and other Indian mythological figures.1 These images, some of which were based on his original oil paintings and commissioned work, made both the gods and fine art accessible to the masses, thereby challenging distinctions between sacred and secular spaces.