立法會 Legislative Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Kwok Wing Hang and Others V Chief Executive in Council and Another

Department of Justice The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Summary of Judgment Kwok Wing Hang and Others v Chief Executive in Council and Another Leung Kwok Hung v Secretary for Justice and Another CACV 541, 542 & 583/2019 (on appeal from HCAL 2945/2019 and 2949/2019); [2020] HKCA 192 Decision : Respondents’ Appeal on (1) the ERO allowed, and (2) the PFCR partially allowed Applicants’ Cross Appeals dismissed Date of Hearing : 9-10 January 2020 Date of Judgment/Decision : 9 April 2020 Background 1. These are the appeals of the Chief Executive in Council (“CEIC”) and the Secretary for Justice (“SJ”), and the cross appeals of Mr Leung Kwok Hung (“Mr Leung”) and 24 Members of the Legislative Council (“LegCo”), against the Judgment of the Court of First Instance (“CFI”) dated 18 November 2019 (“CFI Judgment”) and the Decision of the CFI (on the questions of relief and costs) dated 22 November 2019 (“Decision”) allowing the application for judicial review and holding (i) the Emergency Regulations Ordinance (Cap. 241) (“ERO”) and the Prohibition on Face Covering Regulation (Cap. 241K) (“PFCR”) made thereunder unconstitutional and invalid (“Tier 1 Challenge”); and (ii) PFCR ss.3(1)(b) – (d) and s.5 unconstitutional and void (“Tier 2 Challenge”). 2. The background facts can be found in paras. 1-20 of the Judgment of the Court of Appeal (“CA”).1 3. The grounds for judicial review are repeated in para. 29 of the CA’s Judgment.2 1 In summary, since June 2019, Hong Kong had experienced serious social unrests and public disorders marked by protests, escalating violence, vandalisms and arsons arising from the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019. -

544 Final REPORT from the COMMISSION to the COUNCIL

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 15.9.2003 COM(2003) 544 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Annual Report by the European Commission on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Reaffirmation and implementation of the "one country, two systèmes" 3 3. Institutional developments 5 4. Legislative Developments 7 5. Rights of assembly and demonstration. 10 6. The Economy 11 7. European union - Hong Kong relations. 12 8. Conclusion 14 2 HONG KONG: Annual Report 2002 1. INTRODUCTION As in the Commission’s previous annual reports, this 2002 report aims to assess the state of development of the Hong Kong SAR and its relations with the European Union. In accordance with the Commission’s mandate, the report analyses progress in the implementation of the “One Country, Two Systems” principle, and reviews developments in the legislative, institutional and individual rights fields. The document also provides an assessment of economic developments, and reports on the main aspects of EU-Hong Kong relations. 2. REAFFIRMATION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE “ONE COUNTRY, TWO SYSTEMS” PRINCIPLE - Reaffirmation of the principle The Central Government of Beijing again reiterated its adherence to the “one country, two systems” principle in its official statements. In a speech to the National People’s Congress (NPC) on 5 March 2002, Prime Minister Zhu Rongji stated: “We should fully implement the principle of “one country, two systems” and the Basic Law of Hong Kong and Macao Special Administrative Regions. It is our firm and unswerving objective to maintain the long-term stability, prosperity and development there. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

1998 Human Rights Report - Hong Kong Page 1 of 8

1998 Human Rights Report - Hong Kong Page 1 of 8 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Hong Kong Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1998 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, February 26, 1999. HONG KONG Hong Kong reverted from British to Chinese sovereignty on July 1, 1997. As a Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China, it enjoys a high degree of autonomy except in defense and foreign affairs and remains a free society with legally protected rights. The Basic Law, approved in 1990 by China's National People's Congress, provides for fundamental rights and serves as a "mini constitution." A chief executive, selected by a 400-person selection committee chosen by a China- appointed preparatory committee, wields executive power. A legislature composed of directly and indirectly elected members was sworn in on July 1. Upon reversion, China, which had objected to the electoral rules instituted by the British colonial government, dissolved Hong Kong's first fully elected Legislative Council. A 60-member Provisional Legislature, chosen by the selection committee that named the Chief Executive, took office on July 1, 1997. Critics contended that the selection of the Provisional Legislature had no basis in law and was designed to exclude groups or individuals critical of China. -

4 May 2020 Excellency, We Have the Honour to Address You in Our

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; and the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders REFERENCE: AL CHN 9/2020 4 May 2020 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacities as Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; and Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 41/12, 42/22, 34/18 and 34/5. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning the arrest of 15 pro-democracy activists in connection with their participation in peaceful protests between August and October 2019 in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR). In this regard, we would like to refer your Excellency’s Government to previous communications that Special Procedures sent with regard to the protests in Hong Kong (CHN 12/2019, CHN 2/2020 and CHN 3/2020). We thank you for the response to CHN 12/2019 and the explanations given in the response. However our questions in the communication were not fully answered. According to the information received: Between June and December 2019, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators gathered, the vast majority of them peacefully, to protest against the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation Bill and make further political demands. -

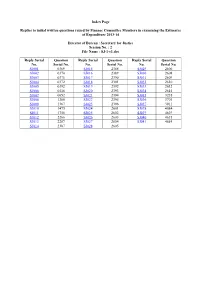

Replies to Initial Written Questions Raised by Finance Committee Members in Examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2013-14

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2013-14 Director of Bureau : Secretary for Justice Session No. : 2 File Name : SJ-1-e1.doc Reply Serial Question Reply Serial Question Reply Serial Question No. Serial No. No. Serial No. No. Serial No. SJ001 0369 SJ015 2388 SJ029 2606 SJ002 0370 SJ016 2389 SJ030 2608 SJ003 0371 SJ017 2390 SJ031 2609 SJ004 0372 SJ018 2391 SJ032 2610 SJ005 0392 SJ019 2392 SJ033 2612 SJ006 0518 SJ020 2393 SJ034 2614 SJ007 0652 SJ021 2394 SJ035 3238 SJ008 1366 SJ022 2395 SJ036 3701 SJ009 1367 SJ023 2396 SJ037 3911 SJ010 1475 SJ024 2601 SJ038 4084 SJ011 1756 SJ025 2602 SJ039 4629 SJ012 2266 SJ026 2603 SJ040 4635 SJ013 2267 SJ027 2604 SJ041 4654 SJ014 2387 SJ028 2605 Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2013-14 Director of Bureau : Secretary for Justice Session No. : 2 Reply Serial Question No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme SJ001 0369 TAM Yiu-chung 92 (2) Civil SJ002 0370 TAM Yiu-chung 92 (2) Civil SJ003 0371 TAM Yiu-chung 92 (3) Legal Policy SJ004 0372 TAM Yiu-chung 92 (3) Legal Policy SJ005 0392 TAM Yiu-chung 92 (1) Prosecutions SJ006 0518 HO Sau-lan, Cyd 92 SJ007 0652 LEUNG Kwok-hung 92 (1) Prosecutions SJ008 1366 HO Chun-yan, Albert 92 (2) Civil SJ009 1367 HO Chun-yan, Albert 92 (1) Prosecutions SJ010 1475 IP LAU Suk-yee, 92 (1) Prosecutions Regina SJ011 1756 MO, Claudia 92 (3) Legal Policy SJ012 2266 LIAO Cheung-kong, 92 (1) Prosecutions Martin -

China's National Security Law for Hong Kong

China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: Issues for Congress Updated August 3, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46473 SUMMARY R46473 China’s National Security Law for Hong Kong: August 3, 2020 Issues for Congress Susan V. Lawrence On June 30, 2020, China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) passed a Specialist in Asian Affairs national security law (NSL) for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Hong Kong’s Chief Executive promulgated it in Hong Kong later the same day. The law is widely seen Michael F. Martin as undermining the HKSAR’s once-high degree of autonomy and eroding the rights promised to Specialist in Asian Affairs Hong Kong in the 1984 Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong, an international treaty between the People’s Republic of China (China, or PRC) and the United Kingdom covering the 50 years from 1997 to 2047. The NSL criminalizes four broadly defined categories of offenses: secession, subversion, organization and perpetration of terrorist activities, and “collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security” in relation to the HKSAR. Persons convicted of violating the NSL can be sentenced to up to life in prison. China’s central government can, at its or the HKSAR’s discretion, exercise jurisdiction over alleged violations of the law and prosecute and adjudicate the cases in mainland China. The law apparently applies to alleged violations committed by anyone, anywhere in the world, including in the United States. The HKSAR and PRC governments have already begun implementing the NSL, including setting up the new entities the law requires. -

BASIC LAW of the HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION of the PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC of CHINA Important Notice

THE BASIC LAW OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Important Notice The information contained in this booklet has no legal status, and is made available for information only and should not be relied on as an official version of the Basic Law and related constitutional instruments herein. Users should refer to the Loose-leaf Edition of the Laws and the Government Gazette for the related official versions. Contents Decree of the President of the People’s Republic of China The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China Preamble ......................................................................................... 1 Chapter I General Principles ............................................................ 2 Chapter II Relationship between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region ................ 5 Chapter III Fundamental Rights and Duties of the Residents ............ 10 Chapter IV Political Structure............................................................. 15 Section 1 The Chief Executive ......................................................... 15 Section 2 The Executive Authorities ................................................ 21 Section 3 The Legislature................................................................. 22 Section 4 The Judiciary.................................................................... 27 Section 5 District Organizations ...................................................... 31 Section -

The Misapplication of Leung Kwok Hung in Hong Kong: Authorizing the Rationality Requirement for Textually Absolute Rights

Washington International Law Journal Volume 19 Number 3 7-1-2010 The Misapplication of Leung Kwok Hung in Hong Kong: Authorizing the Rationality Requirement for Textually Absolute Rights Albert Connor Buchman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Albert C. Buchman, Comment, The Misapplication of Leung Kwok Hung in Hong Kong: Authorizing the Rationality Requirement for Textually Absolute Rights, 19 Pac. Rim L & Pol'y J. 565 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol19/iss3/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington International Law Journal by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2010 Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal Association THE MISAPPLICATION OF LEUNG KWOK HUNG IN HONG KONG: AUTHORIZING THE RATIONALITY REQUIREMENT FOR TEXTUALLY ABSOLUTE RIGHTS Albert Connor Buchman† Abstract: The Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance (BORO) guarantees many fundamental rights to Hong Kong’s permanent residents. In these constitutionally significant statutes, two types of rights exist: 1) textually qualified rights, which contain qualifying language indicating for what purposes a legislated restriction is permissible, such as when necessary for national security, public order, public health or morals, and 2) textually absolute rights, which contain no language indicating when a legislated restriction on that right is permissible. In Leung Kwok Hung & Others v. -

The Public Order Ordinance Has Been Used to Crackdown On, and Imprison, Protestors from Across Hong Kong’S Political Opposition

A TOOL OF LAWFARE : THE ABUSE OF HONG KONG’S PUBLIC ORDER ORDINANCE SINCE 2014 SUMMARY On 22 May 2019, Ray Wong Toi-yeung and Alan Li publicly announced that they were granted refugee status by the government of Germany in May 2018.i Undoubtedly one of the key reasons that the German government made the bold step of granting political asylum to two young Hong Kongers is because of the punitive way that the Public Order Ordinance has been used to crackdown on, and imprison, protestors from across Hong Kong’s political opposition. Mr Wong and Mr Li were facing trial under this law, and therefore could not be guaranteed a fair trial. Hong Kong Watch will publish an in-depth report on this subject in the coming months. This briefing summarises one key argument: that the legislation has been a key tool in the Hong Kong government’s campaign of “lawfare” against Hong Kong’s political opposition. Since the Umbrella Movement, more than 100 democracy activists and protestors have been prosecuted under the Public Order Ordinance, a law which has been repeatedly criticised by the United Nations Human Rights Committee for curtailing freedom of assembly. Following pressure from the government to increase the ‘deterrence effect’ of the legislation in 2017, judges have interpreted offences in recent verdicts using the Public Order Ordinance following a simple approach: maximise the probability of conviction and minimise leniency. This not only further raises the costs of protest and has detrimental effects on civil liberties and political freedoms, it also sets a dangerous precedent for the rule of law.