Gayle Conservation Area Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda to Notify the Clerk of Matters for Inclusion on the Agenda for the Next Meeting

HAWES & HIGH ABBOTSIDE PARISH COUNCIL CLERK: Mrs Karen Prudden Coatie, Bainbridge, Leyburn, North Yorkshire, DL8 3EF Telephone: 01969 650706 E-mail: [email protected] Dear Councillor You are summoned to attend a Meeting of Hawes & High Abbotside Parish Council, starting at 6.30 pm, to be held on THURSDAY 26th AUGUST 2021 via ‘Zoom’. Members of the public wishing to attend this meeting should contact the Clerk in advance to ensure they receive a link to the meeting ================================================================================== MEETING OF HAWES & HIGH ABBOTSIDE PARISH COUNCIL A G E N D A 1. Notification of the Council’s expectations in respect of recording of the meeting 2. Apologies for Absence To receive apologies and approve the reasons for absence. 3. Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of interest not already declared under the Council’s Code of Conduct or members Register of Disclosable Pecuniary Interests. 4. Minutes of the Last Meeting To confirm the Minutes of the Meeting held on 29th June 2021 as a true and correct record and to sign them as such. 5. Ongoing Matters To receive information on the following ongoing issues and decide further action where necessary:- 5.1. To receive an update on the Appersett and Burtersett village signs 5.2. To receive an update on the clearance of overgrown hedges overhanging footpaths 6. Planning Applications To Consider Planning Applications:- 6.1 R/56/520 - Householder Planning Permission for erection of glazed canopy extension and associated alterations -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

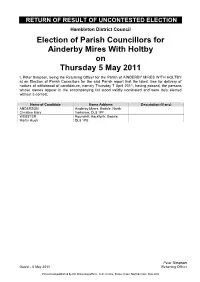

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ainderby Mires With Holtby on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Christine Mary Yorkshire, DL8 1PF WEBSTER Roundhill, Hackforth, Bedale, Martin Hugh DL8 1PB Dated Friday 5 September 2014 Peter Simpson Dated – 5 May 2011 Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton, DL6 2UU RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aiskew - Aiskew on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish Ward of AISKEW - AISKEW at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish Ward report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) LES Forest Lodge, 94 Bedale Road, Carl Anthony Aiskew, Bedale -

Wemmergill Estate 25 Year Management Plan

1 Wemmergill Moor Limited Management Agreement 2017-2042 Stephanie Bird-Halton, Team Leader – Natural England Richard Johnson, Estates Manager – Wemmergill Moor Limited Dave Mitchell, Lead Adviser – Natural England John Pinkney, Head Keeper – Wemmergill Moor Limited Version 2.2, May 2017 2 Contents Page Number Introduction 3 1) The Vision 6 2) Sensitive Features and Sustainable 8 Infrastructure Principles 3) Sustainable Infrastructure 18 Specifications Agreed Infrastructure Map 33 Agreed Infrastructure List 34 4) Vegetation Management Principles 35 5) Bare Peat & Grip Blocking 45 Specifications 6) Monitoring 47 7) Terms & Conditions of the 62 Agreement and signatories References 67 3 Deed of Agreement under Sections 7 and 13 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 THIS DEED OF AGREEMENT is made on the day of 2017 PARTIES (1) Natural England of 4th Floor, Foss House, Kings Pool, 1-2 Peasholme Green, York YO1 7PX ('Natural England'); and (2) Wemmergill Moor Limited, a company incorporated in England and Wales with registered number 4749924 whose registered office is at O’Reilly Chartered Accountants, Kiln Hill, Market Place, Hawes, North Yorkshire, DL8 3RA (“the Land Owner”). Introduction Wemmergill is one of Britain's most historic and prolific grouse moors, with shooting records that date back to 1843. In the late 19th Century members of the Royal Families of Europe, and MPs were regular visitors during the shooting season, staying at Wemmergill Hall (demolished in the 1980's). Sir Fredrick Milbank MP leased the shooting in the late 1860's when the landowner John Bowes, founder of the Bowes Museum, was living in Paris. -

Land & Buildings at Gayle

Land and Buildings at Gayle Gayle, Hawes, North Yorkshire Land and buildings extending to 0.82 Ha (2.03 Ac) For Sale by Private Treaty as a whole or in up to 3 Lots Guide Price for the whole: £85,000 Land and Buildings at Gayle West End, Gayle, Hawes, North Yorkshire, DL8 3RT Situation Rights and Easements The land and buildings are situated at West End, The property will be sold subject to and with the Gayle, near the popular Upper Wensleydale market benefit of all existing rights of way, water, drainage, town of Hawes within the heart of the Yorkshire watercourses, and other easements, quasi or reputed Dales National Park. easements and rights of adjoining owners if any affecting the same and all existing and proposed Description wayleaves and all matters registered by any All together the land and buildings extend to 0.82 competent authority subject to statute. Ha (2.03 Ac), however they are arranged in three separate Lots as described below. Photographs Any fixtures and fittings in the photographs may They come to the market following the Vendor’s not be included in the sale of the property. decision to sell and represent a rare opportunity to acquire some small parcels of land with the benefit Value Added Tax of stone barns in an accessible location. There is It is presumed that the sale of the property will be also potential for the Purchaser(s) to add value to exempt from VAT and that VAT will not be the barns as well as the land through conversion or charged in addition to the purchase price. -

Greengate Farm 97.18 Acres (39.33 Ha) Approx

www.listerhaigh.co.uk GREENGATE FARM 97.18 ACRES (39.33 HA) APPROX. KIRKBY FLEETHAM NEAR NORTHALLERTON, NORTH YORKSHIRE, DL7 0SL A VERSATILE RING FENCED FARM INCLUDING A SUBSTANTIAL BRICK BUILT FARMHOUSE WITH ADJACENT STONE BARNS PROVIDING SCOPE FOR DEVELOPMENT (SUBJECT TO PP), ALL SET WITHIN A RURAL SETTING WITH EXCELLENT CONNECTIVITY TO MAIN ROADS AND THE A1(M). THE FARM ALSO INCLUDES, A BUNGALOW, FURTHER OUTBUILDINGS, MODERN STEEL PORTAL FRAME BUILDINGS AND ARABLE/ GRASSLAND. THE WHOLE FARM EXTENDS TO 97.18 AC (39.33 HA) APPROX. Offers in Excess of £2,000,000 FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY. 106 High Street, Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, HG5 0HN Telephone: 01423 860322 Fax: 01423 860513 E-mail: [email protected] SUMMERBRIDGE, HARROGATE HG3 4JR www.listerhaigh.co.uk LOCATION HOLMELANDS BUNGALOW The farm is situated approximately 0.5 mile west of Holmelands Bungalow is well situated and stands in its Kirkby Fleetham and approximately 1 mile north west own plot just off Greengate Lane and takes full of Great Fencote and Little Fencote. The farm lies advantage of the views over Greengate Farm and the between 40 – 50m above sea level, with road frontage surrounding countryside. onto Greengate Lane and only 3.5 miles north of Junction 51 of the A1 (M). The accommodation briefly comprises two double bedrooms, one bathroom, kitchen, living room and Kirkby Fleetham village benefits from a primary school garden. and is within the catchment of both Bedale and Northallerton Schools. A bus route also services the The property was built circa 1958 and whilst being village along with the popular Black Horse Inn Pub. -

A Grade II Listed Georgian Former Coaching Inn

S. 4324 OLD SALUTATION LOW STREET, LITTLE FENCOTE, NORTHALLERTON DL7 9LR A Grade II Listed Georgian Former Coaching Inn 6 Acres of Land Available by Separate Negotiation Price: £595,000 143 High Street, Northallerton, DL7 8PE Tel: 01609 771959 Fax: 01609 778500 www.northallertonestateagency.co.uk Old Salutation , Low Street, Little Fencote, Northallerton DL7 9LR WE ARE VERY PROUD TO OFFER A SUBSTANTIAL, GRADE II LISTED GEORGIAN FORMER COACHING INN OFFERING THE FOLLOWING: A Very Impressive & Generously Proportioned Georgian Former Coaching Inn With Tremendous Scope for Further Improvement & Extension / Utilisation of 2nd Floor Accommodation Presently a Country Residence of Character, Distinction & Substance Well Laid Out & Attractively Presented 5-Bedroomed Family Accommodation Arranged on Two Floors Superb Vaulted Ceiling Living Kitchen of Immense Character & Distinction with Views to Front & Rear A Host of Original Features Retained & Enhanced By the Present Owners Extensive Third Floor Extending to 6 Bedrooms with Scope To Provide Additional Accommodation, Self-Contained Annexe Etc. Subject to Refurbishment & Building Regulations Attached Double Garage, Workshop & Storage Oil Fired Central Heating Very Attractive Rural Position in Much Sought After Country Location Good Sized, Well Laid Out, Mature Grounds with Extensive Hardstanding & Sweeping Driveway Small Scale Tree Planting & Relaxing Entertainment Area Inspection is Essential to Fully Appreciate the Property, Its Potential & its Attractive Rural Location Available for Early Completion 6 Acres of Land for Sale by Separate Negotiation OLD SALUTATION, LOW STREET, LITTLE FENCOTE, NORTHALLERTON DL7 9LR SITUATION Communications - A.1 and A.19 Trunk roads close by providing Northallerton 6 miles Richmond 8 miles direct access north and south and feeding into the A.66 A1 ½ mile Darlington 16 miles Transpennine . -

Full Edition

THE UPPER WENSLEYDALE NEWSLETTER Issue 229 October 2016 Donation please: 30p suggested or more if you wish Covering Upper Wensleydale from Wensley to Garsdale Head, with Walden and Bishopdale, Swaledale from Keld to Gunnerside plus Cowgill in Upper Dentdale. Published by Upper Wensleydale The Upper Wensleydale Newsletter Newsletter Burnside Coach House, Burtersett Road, Hawes DL8 3NT Tel: 667785 Issue 229 October 2016 Email for submission of articles, what’s ons, letters etc.:[email protected] Features Competition 4 Newsletters on the Web, simply enter ____________________________ “Upper Wensleydale Newsletter” or Swaledale Mountain Rescue 12 ‘‘Welcome to Wensleydale’ Archive copies back to 1995 are in the Dales ________________ ____________ Countryside Museum resources room. Wensleydale Wheels 7 ____________________________ Committee: Alan S.Watkinson, A684 9 and 10 Malcolm Carruthers, ____________________________ Barry Cruickshanks (Web), Police Report 18 Sue E .Duffield, Karen Jones, ____________________________ Alastair Macintosh, Neil Piper, Karen Prudden Doctor’s Rotas 17 Janet W. Thomson (Treasurer), ____________________________ Peter Wood Message from Spain 16 Final processing: ___________________________ Sarah Champion, Adrian Janke. Jane Ritchie 21 Postal distribution: Derek Stephens ____________________________ What’s On 13 ________________________ PLEASE NOTE Plus all the regulars This web-copy does not contain the commercial adverts which are in the full Newsletter. Whilst we try to ensure that all information is As a general rule we only accept adverts from correct we cannot be held legally responsible within the circulation area and no more than for omissions or inaccuracies in articles, one-third of each issue is taken up with them. adverts or listings, or for any inconvenience caused. Views expressed in articles are the - Advertising sole responsibility of the person by lined. -

Hambleton District Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment

Hambleton District Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Hambleton District Council Project Number: 60535354 April 2019 Hambleton District Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Amelia Kent Isla Hoffmann Heap Dr James Riley Ecologist (Grad CIEEM) Senior Ecologist Technical Director Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 0 17/08/18 Draft for client JR James Riley Technical Director review 1 23/10/2018 Final following JR James Riley Technical Director client comments 2 02/05/19 Updated following JR James Riley Technical Director amendments to plan Prepared for: Hambleton District Council AECOM Hambleton District Local Plan Habitats Regulations Assessment Prepared for: Hambleton District Council Prepared by: AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited Midpoint, Alencon Link Basingstoke Hampshire RG21 7PP United Kingdom T: +44(0)1256 310200 aecom.com © 2019 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement -

Askrigg Walk 12.Indd

Walk 12 Mossdale and Cotterdale Distance - 8 miles Map: O.S. Outdoor Leisure 30 - Walk - A684 Disclaimer: This route was correct at time of writing. However, alterations can happen if development or boundary changes occur, and there is no guarantee of permanent access. These walks have been published for use by site visitors on the understanding that neither HPB Management Limited nor any other person connected with Holiday Property Bond is responsible for the safety or wellbeing of those following the routes as described. It is walkers’ own responsibility to be adequately prepared and equipped for the level of walk and the weather conditions and to assess the safety and accessibility of the walk. Walk 12 Mossdale and Cotterdale Distance - 8 miles Map: O.S. Outdoor Leisure 19 There are several hamlets in Wensleydale with names right. Descend into a small copse and cross a stream, then swing seeking a stile located where the wall and a wire fence meet. ending - Sett. Appersett, Burtersett, Countersett and left towards a gate situated alongside a barn. Cross the next Follow a beckside path towards the houses (no M&S or Tesco Marsett being examples. The derivation comes from the field aiming for a gate in the far right corner. Turn left along the hereabouts!) Turn right. farm access road. Norse saetr, which roughly translated means settlement. The hamlet, formerly known as Cotter Town originally When the road swings (right) towards the farmhouse (Birk housed a mining community. In those times there were This outing commences from Appersett, a small hamlet Rigg farm), veer left and pass through a gate. -

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale

Swaledale & Arkengarthdale The two far northern dales, with their The River Swale is one of England’s fastest industry, but in many places you will see iconic farming landscape of field barns and rising spate rivers, rushing its way between the dramatic remains of the former drystone walls, are the perfect place to Thwaite, Muker, Reeth and Richmond. leadmining industry. Find out more about retreat from a busy world and relax. local life at the Swaledale Museum in Reeth. On the moors you’re likely to see the At the head of Swaledale is the tiny village hardy Swaledale sheep, key to the Also in Reeth are great shops showcasing of Keld - you can explore its history at the livelihood of many Dales farmers - and the local photography and arts and crafts: Keld Countryside & Heritage Centre. This logo for the Yorkshire Dales National Park; stunning images at Scenic View Gallery and is the crossing point of the Coast to Coast in the valleys, tranquil hay meadows, at dramatic sculptures at Graculus, as well as Walk and the Pennine Way long distance their best in the early summer months. exciting new artists cooperative, Fleece. footpaths, and one end of the newest It is hard to believe these calm pastures Further up the valley in Muker is cosy cycle route, the Swale Trail (read more and wild moors were ever a site for Swaledale Woollens and the Old School about this on page 10). Gallery. The glorious wildflower meadows of Muker If you want to get active, why not learn navigation with one of the companies in the area that offer training courses or take to the hills on two wheels with Dales Bike Centre.