The Commodification of Rajasthani Folk Performance at Chokhi Dhani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

Castes and Caste Relationships

Chapter 4 Castes and Caste Relationships Introduction In order to understand the agrarian system in any Indian local community it is necessary to understand the workings of the caste system, since caste patterns much social and economic behaviour. The major responses to the uncertain environment of western Rajasthan involve utilising a wide variety of resources, either by spreading risks within the agro-pastoral economy, by moving into other physical regions (through nomadism) or by tapping in to the national economy, through civil service, military service or other employment. In this chapter I aim to show how tapping in to diverse resource levels can be facilitated by some aspects of caste organisation. To a certain extent members of different castes have different strategies consonant with their economic status and with organisational features of their caste. One aspect of this is that the higher castes, which constitute an upper class at the village level, are able to utilise alternative resources more easily than the lower castes, because the options are more restricted for those castes which own little land. This aspect will be raised in this chapter and developed later. I wish to emphasise that the use of the term 'class' in this context refers to a local level class structure defined in terms of economic criteria (essentially land ownership). All of the people in Hinganiya, and most of the people throughout the village cluster, would rank very low in a class system defined nationally or even on a district basis. While the differences loom large on a local level, they are relatively minor in the wider context. -

Agritourism Advantage Rajasthan

GLOBAL RAJASTHAN AGRITECH MEET 9-11 NOV 2016 JAIPUR AGRITOURISM ADVANTAGE RAJASTHAN Agritourism Advantage Rajasthan 1 Agritourism 2 Advantage Rajasthan TITLE Agritourism: Advantage Rajasthan YEAR November, 2016 AUTHORS Strategic Government Advisory (SGA), YES BANK Ltd Special &ĞĚĞƌĂƟŽŶŽĨ/ŶĚŝĂŶŚĂŵďĞƌƐŽĨŽŵŵĞƌĐĞΘ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌLJ;&//Ϳ Acknowledgement EŽƉĂƌƚŽĨƚŚŝƐƉƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶŵĂLJďĞƌĞƉƌŽĚƵĐĞĚŝŶĂŶLJĨŽƌŵďLJƉŚŽƚŽ͕ƉŚŽƚŽƉƌŝŶƚ͕ŵŝĐƌŽĮůŵŽƌĂŶLJŽƚŚĞƌ KWzZ/',d ŵĞĂŶƐǁŝƚŚŽƵƚƚŚĞǁƌŝƩĞŶƉĞƌŵŝƐƐŝŽŶŽĨz^E<>ƚĚ͘ dŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚŝƐƚŚĞƉƵďůŝĐĂƟŽŶŽĨz^E<>ŝŵŝƚĞĚ;͞z^E<͟ͿĂŶĚ&//ƐŽz^E<ĂŶĚ&//ŚĂǀĞĞĚŝƚŽƌŝĂů ĐŽŶƚƌŽůŽǀĞƌƚŚĞĐŽŶƚĞŶƚ͕ŝŶĐůƵĚŝŶŐŽƉŝŶŝŽŶƐ͕ĂĚǀŝĐĞ͕ƐƚĂƚĞŵĞŶƚƐ͕ƐĞƌǀŝĐĞƐ͕ŽīĞƌƐĞƚĐ͘ƚŚĂƚŝƐƌĞƉƌĞƐĞŶƚĞĚŝŶ ƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͘,ŽǁĞǀĞƌ͕z^E<͕&//ǁŝůůŶŽƚďĞůŝĂďůĞĨŽƌĂŶLJůŽƐƐŽƌĚĂŵĂŐĞĐĂƵƐĞĚďLJƚŚĞƌĞĂĚĞƌ͛ƐƌĞůŝĂŶĐĞ ŽŶŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶŽďƚĂŝŶĞĚƚŚƌŽƵŐŚƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͘dŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚŵĂLJĐŽŶƚĂŝŶƚŚŝƌĚƉĂƌƚLJĐŽŶƚĞŶƚƐĂŶĚƚŚŝƌĚͲƉĂƌƚLJ ƌĞƐŽƵƌĐĞƐ͘ z^ E< ĂŶĚͬŽƌ &// ƚĂŬĞ ŶŽ ƌĞƐƉŽŶƐŝďŝůŝƚLJ ĨŽƌ ƚŚŝƌĚ ƉĂƌƚLJ ĐŽŶƚĞŶƚ͕ ĂĚǀĞƌƟƐĞŵĞŶƚƐ Žƌ ƚŚŝƌĚ ƉĂƌƚLJĂƉƉůŝĐĂƟŽŶƐƚŚĂƚĂƌĞƉƌŝŶƚĞĚŽŶŽƌƚŚƌŽƵŐŚƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͕ŶŽƌĚŽĞƐŝƚƚĂŬĞĂŶLJƌĞƐƉŽŶƐŝďŝůŝƚLJĨŽƌƚŚĞŐŽŽĚƐ Žƌ ƐĞƌǀŝĐĞƐ ƉƌŽǀŝĚĞĚ ďLJ ŝƚƐ ĂĚǀĞƌƟƐĞƌƐ Žƌ ĨŽƌ ĂŶLJ ĞƌƌŽƌ͕ŽŵŝƐƐŝŽŶ͕ ĚĞůĞƟŽŶ͕ ĚĞĨĞĐƚ͕ ƚŚĞŌ Žƌ ĚĞƐƚƌƵĐƟŽŶ Žƌ ƵŶĂƵƚŚŽƌŝnjĞĚĂĐĐĞƐƐƚŽ͕ŽƌĂůƚĞƌĂƟŽŶŽĨ͕ĂŶLJƵƐĞƌĐŽŵŵƵŶŝĐĂƟŽŶ͘&ƵƌƚŚĞƌ͕z^E<ĂŶĚ&//ĚŽŶŽƚĂƐƐƵŵĞ ĂŶLJƌĞƐƉŽŶƐŝďŝůŝƚLJŽƌůŝĂďŝůŝƚLJĨŽƌĂŶLJůŽƐƐŽƌĚĂŵĂŐĞ͕ŝŶĐůƵĚŝŶŐƉĞƌƐŽŶĂůŝŶũƵƌLJŽƌĚĞĂƚŚ͕ƌĞƐƵůƟŶŐĨƌŽŵƵƐĞŽĨ ƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚŽƌĨƌŽŵĂŶLJĐŽŶƚĞŶƚĨŽƌĐŽŵŵƵŶŝĐĂƟŽŶƐŽƌŵĂƚĞƌŝĂůƐĂǀĂŝůĂďůĞŽŶƚŚŝƐƌĞƉŽƌƚ͘dŚĞĐŽŶƚĞŶƚƐĂƌĞ ƉƌŽǀŝĚĞĚĨŽƌLJŽƵƌƌĞĨĞƌĞŶĐĞŽŶůLJ͘ dŚĞƌĞĂĚĞƌͬďƵLJĞƌƵŶĚĞƌƐƚĂŶĚƐƚŚĂƚĞdžĐĞƉƚĨŽƌƚŚĞŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶ͕ƉƌŽĚƵĐƚƐĂŶĚƐĞƌǀŝĐĞƐĐůĞĂƌůLJŝĚĞŶƟĮĞĚĂƐ ďĞŝŶŐƐƵƉƉůŝĞĚďLJz^E<ĂŶĚ&//ĚŽŶŽƚŽƉĞƌĂƚĞ͕ĐŽŶƚƌŽůŽƌĞŶĚŽƌƐĞĂŶLJŽƚŚĞƌŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶ͕ƉƌŽĚƵĐƚƐ͕Žƌ -

Haryana Government Gazette

Haryana Government Gazette EXTRAORDINARY Published by Authority © Govt. of Haryana No. 21-2021/Ext.] CHANDIGARH, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 (MAGHA 20, 1942 SAKA) HARYANA GOVERNMENT PERSONNEL DEPARTMENT Notification The 9th February, 2021 No. 42/1/2018-5SII – In pursuance of the Rule 11(1) of the Haryana Civil Services (Executive Branch) Rules, 2008 and in supersession of Notification No. 42/1/95-5SII, dated 6th November, 2008, the Governor of Haryana is pleased to order that the syllabi for the Preliminary Examination as well as Main Written Examination for the posts of Haryana Civil Service (Executive Branch) and Allied Services shall be as under:- SYLLABI FOR THE PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION 1. GENERAL STUDIES General Science. Current events of national and international importance. History of India and Indian National Movement. Indian and World Geography. Indian Culture, Indian Polity and Indian Economy. General Mental Ability. Haryana-Economy and people. Social, economic and culture institutions and language of Haryana. Questions on General Science will cover general appreciation and understanding of science including matters of everyday observation and experience, as may be expected of a well educated person who has not made a special study of any particular scientific discipline. In current events, knowledge of significant national and international events will be tested. In History of India, emphasis will be on broad general understanding of the subject in its social, economic and political aspects. Questions on the Indian National Movement will relate to the nature and character of the nineteenth century resurgence, growth of nationalism and attainment of Independence. In Geography, emphasis will be on Geography of India. -

Reflection of Regional Culture and Image in the Form of Culinary Tourism: Rajasthan Dr

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) Volume 5 Issue 1, November-December 2020 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 – 6470 Reflection of Regional Culture and Image in the Form of Culinary Tourism: Rajasthan Dr. Gaurav Bhattacharya, Dr. Manoj Srivastava, Mr Arun Gautam School of Hotel Management, Manipal University Jaipur, Rajasthan, India ABSTRACT How to cite this paper: Dr. Gaurav Since time immemorial, food has been an integral part of any culture. Any Bhattacharya | Dr. Manoj Srivastava | Mr gathering of people, will in one way or another involve food in some form. Arun Gautam "Reflection of Regional Culturally, sharing of food induces social bonding; and, as humans are social Culture and Image in the Form of Culinary by nature, food becomes an integral part of the society. This paper attempts to Tourism: Rajasthan" research and document the roots of this amalgamation of culinary tourism Published in with culture and describe ways and means for showcasing and, hence, International Journal preserving the same. Since the topic is extremely wide in its scope, the focus of of Trend in Scientific the case study has purposely been limited to the state of Rajasthan in India. Research and Development (ijtsrd), Rajasthan, popularly known to many as the Land of the Kings, is a beautiful ISSN: 2456-6470, example of India’s age-old opulence and grandeur, traces of which still linger IJTSRD38102 Volume-5 | Issue-1, in the air of this state. One of the most colourful and vibrant states in the December 2020, pp.1034-1041, URL: country, with a strong blend of culture, history, music, cuisine and people www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd38102.pdf wholeheartedly offering hospitality, it’s quite easy falling in love with Rajasthan. -

The Incredible Cultural Heritage of Rajasthan

ISSN No. : 2394-0344 Remarking : Vol-2 * Issue-2*July-2015 The Incredible Cultural Heritage of Rajasthan Abstract Rajasthan, a land of tremendous architecture, music, dance, dresses, arts and crafts, and paintings has artistic and cultural traditions which reflect the ancient Indian way of life. There is a rich and varied folk culture from villages which is often depicted symbolic after state. Cultural heritage of Rajasthan is rich and carefully nurtured and sustained over centuries by waves of settlers ranging from Harappan civilization, Aryans, Bhils, Jats, Gujjars, Muslims and Rajput Aristocracy. The state is known for its arts and crafts , sculpture, paintings, meenakari work, colourful dresses, beautiful fairs and festivals, spectacular folk dance and music, ivory jewellery, marvellous architecture etc. Keywords: Tourist destination, Pad, Meenakari work, Architecture, Craft, Miniature Paintings, Ivory, Lac and Glass. Introduction Rajasthan, a land of Rajas and Maharajas, elephants and camels, places and forts, dance and music is not only a jewel among the tourism hotspots of Indians but is also one of the most popular tourist destinations of several thousands of foreigners every year. Rajasthan has a glorious history. It is known for many brave kings, their deeds, and their interest in art and architecture. Rajasthan exhibits the sole example in the history of mankind of a people withstanding every outrage barbarity can inflict or human nature sustain and bent to the earth, yet rising buoyant from the pressure and Prashant Dwivedi making calamity a whetstone to courage. Its name means “the land of Assistant Professor, Rajas.” It was also called Rajputana (the country of the Rajputs). -

EBSB Monthly Report February 2021

भारतीय सूचना Indian Institute of ौोगक संान Information Technology Guwahati गुवाहाट A Dissemination Report on THEATER AND DRAMATICS IN RAJASTHAN EBSB Monthly Report February, 2021 Ek Bharat Submitted to Shreshtha Bharat MoE, Govt. of India THEATER AND 01 DRAMATICS IN RAJASTHAN Rajasthan, an inseparable part of India. When it comes to culture in India, Rajasthan plays a very role in it. One of the way to show the culture and values in Rajasthan is their folk dramas and theater. Rajasthani dramatics art is also very diverse in Rajasthan itself like Marwari, Dundari, Shekhawati, Hadoti, Mewari etc. Also there are lot of different style of theater and dramas like Khayal, Swang, Rammat, Phad, Nautanki, Bhawai, Gawari etc. they have their own different style of performance and context. "RAJASTHANI DRAMATICS ART IS VERY DIVERSE IN RAJASTHAN" KHAYAL is one of the most prominent form of folk theatrical art in Rajasthan. The origin of the Khayal is around of 18th century. The subject of Khayal is based on the mythological and ancient stories. Due to diversity of culture of Rajasthan, Khayal theater has different form based on city, performing style or on the name of author. Some of the famous Khayal are like Kuchamani Khayal Shekhawati Khayal Jaipuri Khayal Ali bakshi Khayal Turra kalingi Khayal Kishangarhi Khayal Hathrasi Khayal Nautanki Khayal THEATER AND 02 DRAMATICS IN RAJASTHAN TAMASHA is folk drama which began in Jaipur during the times of Maharaja Pratap Singh. Bhatt family had an important role to introduce Tamasha and Drupad gayaki at that time in Rajasthan. -

RAJRAS Rajasthan Current Affairs of 2017

RAJRAS Rajasthan Current Affairs of 2017 Rajasthan Current Affairs Index Persons in NEWS ................................................................................................................................ 3 Places in NEWS .................................................................................................................................. 5 Schemes & Policy ............................................................................................................................. 10 General NEWS ................................................................................................................................. 16 New Initiatives ................................................................................................................................. 21 Science & Technology ...................................................................................................................... 23 RAJRAS Rajasthan Current Affairs Persons in NEWS Mrs. Santosh Ahlawat • Member of Parliament from Jhunjhunu, Mrs. Santosh Ahlawat has been entrusted with the responsibility of representing India at the 72nd UN General Assembly session. Along with Mrs Santosh Ahalawat, the former Union Minister Smt. Renuka Chowdhury and the Rajya Sabha nominated MP, Mr. Swapan Dasgupta will also be present in the conference. Alphons Kannanthanam • Union minister of state for tourism Alphons Kannanthanam was elected unopposed to Rajya Sabha from Rajasthan. He was the lone candidate for the by-poll for the Rajya Sabha seat, -

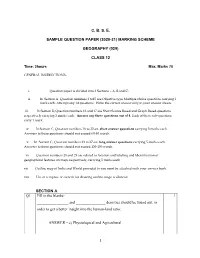

Marking Scheme Geography

C. B. S. E. SAMPLE QUESTION PAPER (2020-21) MARKING SCHEME GEOGRAPHY (029) CLASS 12 Time: 3hours Max. Marks 70 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS- i. Question paper is divided into 3 Sections – A, B and C. ii. In Section A Question numbers 1 to15 are Objective type Multiple choice questions carrying 1 mark each. Attempt any 14 questions. Write the correct answer only in your answer sheets. iii. In Section B, Question numbers 16 and 17 are Short Source Based and Graph Based questions respectively carrying 3 marks each. Answer any three questions out of 4. Each of these sub-questions carry 1 mark . iv. In Section C, Question numbers 18 to 22 are short answer questions carrying 3 marks each. Answers to these questions should not exceed 60-80 words. v. In Section C, Question numbers 23 to 27 are long answer questions carrying 5 marks each. Answers to these questions should not exceed 120-150 words. vi. Question numbers 28 and 29 are related to location and labeling and Identification of geographical features on maps respectively, carrying 5 marks each. vii. Outline map of India and World provided to you must be attached with your answer book. viii. Use of template or stencils for drawing outline maps is allowed. SECTION A Q1 Fill in the blanks- 1 ________________ and _______________ densities should be found out, in order to get a better insight into the human-land ratio: ANSWER – c) Physiological and Agricultural 1 Q2 Arrange the following approaches in a correct order according to their 1 development 1. Spatial organization 2. -

Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India General Background and Ecology

Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India General Background and Ecology of Vertebrates B.K. Sharma ● Seema Kulshreshtha Asad R. Rahmani Editors Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India General Background and Ecology of Vertebrates Editors Dr. B.K. Sharma Dr. Seema Kulshreshtha Associate Professor & Head Associate Professor & Head Department of Zoology Department of Zoology RL Saharia Government PG College Government Shakambhar PG College Kaladera (Jaipur), Rajasthan, India Sambhar Lake (Jaipur) , Rajasthan, India Dr. Asad R. Rahmani Director Bombay Natural History Society Mumbai , Maharashtra, India ISBN 978-1-4614-0799-7 ISBN 978-1-4614-0800-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-0800-0 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012954287 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, speci fi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on micro fi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied speci fi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Water Pressure

By Fen Montaigne Photographs by Peter Essick How can such a wet planet be so short on clean fresh water? The latest installment in the "Challenges for Humanity" series plumbs the problem. Rajendra Singh came to the village, bringing with him the promise of water. If ever a place needed moisture, this hamlet in the desiccated Indian state of Rajasthan was it. Always a dry spot, Rajasthan had suffered several years of drought, leaving remote villages like Goratalai with barely enough water to quench the thirst of their inhabitants. Farm plots had shriveled, and men had fled to the cities seeking work, leaving those behind to subsist on roti, corn, and chili paste. Desperate villagers appealed to a local aristocratic family, who in turn contacted Singh, a man renowned across western India for his ability to use traditional methods of capturing monsoon rains to supply water year-round. Singh arrived in Goratalai on a warm ankle bracelets jangling as they walked. February morning. The sky was robin's egg After a few minutes Singh—dressed in a blue, the same color it had been since light-golden blouse that fell to his knees and August when, everyone recalled, the last white pants—directed villagers to place rains had fallen. He was greeted by a group stones in a 75-yard (68- meter) line between of about 50 people waiting in a dirt square two hills. "This is an ideal site," he under a banyan tree. The men wore loose- announced. His organization, Tarun Bharat fitting cotton pantaloons and turbans of Sangh, would provide the engineering orange, maroon, and white. -

Some Facts About Rajasthan 2020 Pdf

Some facts about rajasthan 2020 pdf Continue State in Northern India This article is about the Indian state. In the area of the ancient city of Samarkand you can see Registan. For the desert in Afghanistan, see Rigestan. The state in IndiaRajasthanState from above, from left to right: Tar Desert, Gateshwar Mahadeva Temple in Chittorgarha, Jantar Mantar, Jodhpur Blue City, Mount Abu, Amer Fort Seal of Rajasthan in IndiaCoordinates (Jaipur): 26'36'N 73'48'E / 26.6'N 73.8'E / 26.6; 73.8Coordinates: 26'36'N 73'48'E / 26.6'N 73.8'E / 26.6; 73.8Country IndiaEstablished30 March 1949CapitalJaipurLargest cityJaipurDistricts List AjmerAlwarBanswaraBaranBarmerBharatpurBhilwaraBikanerBundiChittorgarhChuruDausaDholpurDungarpurHanumangarhJaipurJaisalmerJalorJhalawarJhunjhunuJodhpurKarauliKotaNagaurPaliPratapgarhRajsamandSawai MadhopurSikarSirohiSri GanganagarTonkUdaipur Government • BodyGovernment of Rajasthan • GovernorKalraj Mishra[1] • Chief MinisterAshok Gehlot (INC) • LegislatureUnicameral (200 seats) • Parliamentary constituencyRajya Sabha (10 seats)Lok Sabha (25 seats) • High CourtRajasthan High CourtArea • Total342,239 km2 (132,139 sq mi)Area rank1stPopulation (2011)[2] • Total68,548,437 • Rank7th • Density200/km2 (520/sq mi)Demonym(s)RajasthaniGSDP (2019–20)[3] • Total₹10.20 lakh crore (US$140 billion) • Per capita₹118,159 (US$1,700)Languages[4] • OfficialHindi • Additional officialEnglish • RegionalRajasthaniTime zoneUTC+05:30 (IST)ISO 3166 codeIN-RJVehicle registrationRJ-HDI (2018) 0.629[5]medium · 29thLiteracy (2011)66.1% Sex ratio (2011)928 ♀/1000 ♂'6'websiteRajasthan.gov.inSymbols Rajast The EmblemEmblem of Rajasthan Dance GhoomarMammal Camel and ChinkaraBird GodawanFlower RohidaTree KhejriGame Basketball Rajasthan (/ˈrɑːdʒəstæn/Hindu pronunciation: raːdʒəsˈthaːn (listen); literally, Land of Kings is a state in northern India. The state covers an area of 342,239 square kilometers (132,139 square miles), or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographic area.