The Anthony Perkins Saga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2007 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The life and career of actor Anthony Perkins seems almost like a movie script from the times in which he lived. One of the dark, vulnerable anti-heroes who gained popularity during Hollywood's "post-golden" era, Perkins began his career as a teen heartthrob and ended it unable to escape the role of villain. In his personal life, he often seemed as tortured as the troubled characters he played on film, hiding--and perhaps despising--his true nature while desperately seeking happiness and "normality." Perkins was born on April 4, 1932 in New York City, the only child of actor Osgood Perkins and Janet Esseltyn Rane. His father died when he was only five, and Perkins was reared by his strong-willed and possibly abusive mother. He followed his father into the theater, joining Actors Equity at the age of fifteen and working backstage until he got his first acting roles in summer stock productions of popular plays like Junior Miss and My Sister Eileen. He continued to hone his acting skills while attending Rollins College in Florida, performing in such classics as Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest. Perkins was an unhappy young man, and the theater provided escape from his loneliness and depression. "There was nothing about me I wanted to be," he told Mark Goodman in a People Weekly interview. "But I felt happy being somebody else." During his late teens, Perkins went to Hollywood and landed his first film role in the 1953 George Cukor production, The Actress, in which he appeared with Spencer Tracy. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

One-Word Movie Titles

One-Word Movie Titles This challenging crossword is for the true movie buff! We’ve gleaned 30 one- word movie titles from the Internet Movie Database’s list of top 250 movies of all time, as judged by the website’s users. Use the clues to find the name of each movie. Can you find the titles without going to the IMDb? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 EclipseCrossword.com © 2010 word-game-world.com All Rights Reserved. Across 1. 1995, Mel Gibson & James Robinson 5. 1960, Anthony Perkins & Vera Miles 7. 2000, Russell Crowe & Joaquin Phoenix 8. 1996, Ewan McGregor & Ewen Bremner 9. 1996, William H. Macy & Steve Buscemi 14. 1984, F. Murray Abraham & Tom Hulce 15. 1946, Cary Grant & Ingrid Bergman 16. 1972, Laurence Olivier & Michael Caine 18. 1986, Keith David & Forest Whitaker 21. 1979, Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver 22. 1995, Robert De Niro & Sharon Stone 24. 1940, Laurence Olivier & Joan Fontaine 25. 1995, Al Pacino & Robert De Niro 27. 1927, Alfred Abel & Gustav Fröhlich 28. 1975, Roy Scheider & Robert Shaw 29. 2000, Jason Statham & Benicio Del Toro 30. 2000, Guy Pearce & Carrie-Anne Moss Down 2. 2009, Sam Worthington & Zoe Saldana 3. 2007, Patton Oswalt & Iam Holm (voices) 4. 1958, James Stuart & Kim Novak 6. 1974, Jack Nicholson & Faye Dunaway 10. 1982, Ben Kingsley & Candice Bergen 11. 1990, Robert De Niro & Ray Liotta 12. 1986, Sigourney Weaver & Carrie Henn 13. 1942, Humphrey Bogart & Ingrid Bergman 17. -

FILMS and THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2

FILMS AND THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2. TGTBATU: CE The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Clint Eastwood 3. RFTS: KM Reach for the Sky: Kenneth More 4. FG; TH Forest Gump: Tom Hanks 5. TGE: SM/CB The Great Escape: Steve McQueen and Charles Bronson ( OK. I got it wrong!) 6. TS: PN/RR The Sting: Paul Newman and Robert Redford 7. GWTW: VL Gone with the Wind: Vivien Leigh 8. MOTOE: PU Murder on the Orient Express; Peter Ustinov (but it wasn’t it was Albert Finney! DOTN would be correct) 9. D: TH/HS/KB Dunkirk: Tom Hardy, Harry Styles, Kenneth Branagh 10. HN: GC High Noon: Gary Cooper 11. TS: JN The Shining: Jack Nicholson 12. G: BK Gandhi: Ben Kingsley 13. A: NK/HJ Australia: Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman 14. OGP: HF On Golden Pond: Henry Fonda 15. TDD: LM/CB/TS The Dirty Dozen: Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas 16. A: MC Alfie: Michael Caine 17. TDH: RDN The Deer Hunter: Robert De Niro 18. GWCTD: ST/SP Guess who’s coming to Dinner: Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier 19. TKS: CF The King’s Speech: Colin Firth 20. LOA: POT/OS Lawrence of Arabia: Peter O’Toole, Omar Shariff 21. C: ET/RB Cleopatra: Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton 22. MC: JV/DH Midnight Cowboy: Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman 23. P: AP/JL Psycho: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh 24. TG: JW True Grit: John Wayne 25. TEHL: DS The Eagle has landed: Donald Sutherland. 26. SLIH: MM Some like it Hot: Marilyn Monroe 27. -

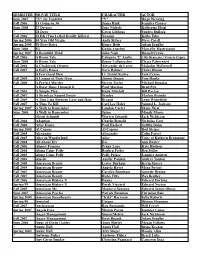

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Tab Hunter Confidential, LLC

Tab Hunter Confidential, LLC. “TAB HUNTER CONFIDENTIAL” FEBRUARY 25, 2015 TRANSCRIBED BY: WORD OF MOUTH (RL) [00:00:26] TAB HUNTER : I would go out occasionally to a cocktail party and I was fascinated by all of what I saw there. There were a few guys dancing with a few guys, a couple of gals dancing with a couple of gals. It was just a party and people were dancing and having a good time. Parties like this were illegal. [00:00:53] And then the next thing I know the cops came in. Doors burst open, there they were. They were arresting a bunch of, uh, queers. They took us down to the police station. You know, I thought oh my God, this is terrible. I thought what would my mother think of my being arrested? Will it affect this career that I’m trying to get started in motion pictures? [00:01:27] An attorney, Harry Weiss appeared. He was well known for taking care of situations like that with many, many Hollywood people. He said you gotta be a lot sharper than you are. You’re in Hollywood now, you want to be an actor, and really laid down the Tab Hunter Confidential - 2 law to me. And then I was released. I had no idea it was gonna jump up and be thrown out at me years later. [00:01:57] [FILM CLIP] DICK CLARK : Here’s the young fellow you’ve been waiting for. Ladies and gentleman, Tab Hunter. VOICEOVER : Six feet of rugged manhood to stir the heart of every woman. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. July 13, 2020 to Sun. July 19, 2020 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. July 13, 2020 to Sun. July 19, 2020 Monday July 13, 2020 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Paul McCartney - Rockshow Rock Legends Paul McCartney and Wings live on stage in a concert that is destined to live forever. In 1976, Jerry Lee Lewis - Jerry Lee Lewis is a piano-playing rock ‘n roll pioneer famous for his high energy Wings undertook an epic world tour which brought their music to a live audience of two million stage presence and controversial life. people in ten countries, an experience captured on the Wings over America triple album. Fully restored and remastered from the original film and audio masters, this is Wings at their best - in 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT concert, on film, at last. Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar Aloha Fleetwood - Sammy travels to Maui to visit with Fleetwood Mac founder Mick Fleetwood. 7:45 PM ET / 4:45 PM PT The Maui neighbors catch up on music and art and jump on stage at Fleetwoods on Front Street AXS TV Insider to perform a Fleetwood Mac classic! Featuring highlights and interviews with the biggest names in music. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Premiere The Big Interview 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Benicio Del Toro - Oscar winner and star of the current hit Sicario talks about making it in Hol- Nothing But Trailers lywood. Plus, his advice for those who want to become successful actors. -

Alonetogether March 2021

#AloneTogether March 2021 We’ve put together some small activities for you to enjoy this month. We hope you take joy from the fact that lots of neighbours across Liverpool will be completing these activities at home, at the same time as you. 3rd March is Alexander Graham Bell’s birthday. He was born on this day 174 years ago! The Scottish-born inventor, scientist, and engineer is credited with inventing and patenting the telephone. Task: Think of an invention, it can be anything in the world! Maybe you’d invent something to make your life a little easier? Or something that would entertain you when you get bored of your books, TV and phone? Something that will cook your dinner for you? Write down everything about your new invention and draw a picture of how you want it to look. The Academy awards, also known as the Oscars, are postponed this year. They’re usually in February, so we’re really missing all of the buzz that comes with this famous awards ceremony! Here’s a 60s film quiz to keep you going until April, when the Oscars will go ahead. (Answers on the last page). 1. Which film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1960? 2. Which actor won the Oscar for Best Actor for his role in the 1962 film To Kill a Mockingbird? 3. Which film was the highest grossing release of 1963, yet still lost money because it was one of the most expensive films ever made? 4. Who played the role of Norman Bates in the 1960 horror movie, Psycho? 5. -

Der Unbeugsame: Paul Newman the EFFECT of GAMMA RAYS on MAN-IN-THE-MOON MARIGOLDS the EFFECT of GAMMA RAYS P Aul Newman Bei Den Dreharbeiten Zu

Der Unbeugsame: Paul Newman THE EFFECT OF GAMMA RAYS ON MAN-IN-THE-MOON MARIGOLDS THE EFFECT OF GAMMA RAYS zu aul Newman bei den Dreharbeiten P Gern wies Paul Newman darauf hin, wie oft er im Leben gomery Clift das Spiel auf der Bühne und das Spielen unverschämtes Glück hatte – typisch für seinen selbst- für den Film neu definierten. ironischen Charme nannte er sich »the luckiest son-of- Zu Beginn von Newmans Karriere war viel die Rede a-bitch«. Das Glück bestand nicht nur darin, dass er zur davon, dass er Brando zu ähnlich sehe. Elia Kazan schlug Paul Newman Paul rechten Zeit am rechten Ort war, es begann schon weit- seinem Produzenten Budd Schulberg schon 1953 vor, aus früher, als »gute Samenreise mit günstigem An- ihn statt Brando für ON THE WATERFRONT (DIE FAUST 36 schluss im Mutterleib für glückliche Gene« (»For me, IM NACKEN, 1954) zu nehmen: »Der Junge wird garan- being lucky starts when you have a good sperm ride tiert ein Filmstar. Nicht der geringste Zweifel. Er sieht that makes a good womb connection that produces lu- genauso gut aus wie Brando, und seine starke männli- cky genes.«) Die genetische Grundausstattung war che Ausstrahlung ist unmittelbarer. Als Schauspieler ist schon vom Äußeren her beachtlich: ein griechischer er noch nicht so gut wie Brando, womöglich wird er es Gott aus dem Mittleren Westen, mit den blauesten Au- nie. Aber er ist ein verflucht guter Schauspieler mit reich- gen seit Frank Sinatra. lich Energie, reichlich Innenleben, reichlich Sex.« Er kam am 26. Januar 1925 in Ohio zur Welt, dien- Da er stets sein Glück betonte, erscheint es nur te im Zweiten Weltkrieg im Pazifik und ging dann nach passend, dass sein Durchbruch mit dem Film SOME- New York. -

IN PERSON & PREVIEWS Talent Q&As and Rare Appearances

IN PERSON & PREVIEWS Talent Q&As and rare appearances, plus a chance for you to catch the latest film and TV before anyone else TV Preview: World on Fire + Q&A with writer Peter Bowker plus cast TBA BBC-Mammoth Screen 2019. Lead dir Adam Smith. With Helen Hunt, Sean Bean, Lesley Manville, Jonah Hauer- King. Ep1 c.60min World on Fire is an adrenaline-fuelled, emotionally gripping and resonant drama, written by the award-winning Peter Bowker (The A Word, Marvellous). It charts the first year of World War Two, told through the intertwining fates of ordinary people from Britain, Poland, France, Germany and the United States as they grapple with the effect of the war on their everyday lives. Join us for a Q&A and preview of this new landmark series boasting a stellar cast, headed up by Helen Hunt and Sean Bean. TUE 3 SEP 18:15 NFT1 TV Preview: Temple + Q&A with writer Mark O’Rowe, exec producer Liza Marshall, actor Mark Strong, and further cast TBA Sky-Hera Pictures 2019. Dirs Luke Snellin, Shariff Korver, Lisa Siwe. With Mark Strong, Carice van Houten, Daniel Mays, Tobi King Bakare. Eps 1 and 2, 80min Temple tells the story of Daniel Milton (Strong), a talented surgeon whose world is turned upside down when his wife contracts a terminal illness. Yet Daniel refuses to accept the cards he’s been dealt. He partners with the obsessive, yet surprisingly resourceful, misfit Lee (Mays) to start a literal ‘underground’ clinic in the vast network of tunnels beneath Temple tube station in London.