UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE COW in the ELEVATOR an Anthropology of Wonder the COW in the ELEVATOR Tulasi Srinivas

TULASI SRINIVAS THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF WONDER THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR tulasi srinivas THE COW IN THE ELEVATOR An Anthropology of Won der Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer ic a on acid-f ree paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Cover designed by Julienne Alexander Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Srinivas, Tulasi, author. Title: The cow in the elevator : an anthropology of won der / Tulasi Srinivas. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2017049281 (print) | lccn 2017055278 (ebook) isbn 9780822371922 (ebook) isbn 9780822370642 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822370796 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Ritual. | Religious life—H induism. | Hinduism and culture— India— Bangalore. | Bangalore (India)— Religious life and customs. | Globalization—R eligious aspects. Classification: lcc bl1226.2 (ebook) | lcc bl1226.2 .s698 2018 (print) | ddc 294.5/4— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2017049281 Cover art: The Hindu goddess Durga during rush hour traffic. Bangalore, India, 2013. FotoFlirt / Alamy. For my wonderful mother, Rukmini Srinivas contents A Note on Translation · xi Acknowl edgments · xiii O Wonderful! · xix introduction. WONDER, CREATIVITY, AND ETHICAL LIFE IN BANGALORE · 1 Cranes in the Sky · 1 Wondering about Won der · 6 Modern Fractures · 9 Of Bangalore’s Boomtown Bourgeoisie · 13 My Guides into Won der · 16 Going Forward · 31 one. ADVENTURES IN MODERN DWELLING · 34 The Cow in the Elevator · 34 Grounded Won der · 37 And Ungrounded Won der · 39 Back to Earth · 41 Memorialized Cartography · 43 “Dead- Endu” Ganesha · 45 Earthen Prayers and Black Money · 48 Moving Marble · 51 Building Won der · 56 interlude. -

Shaiva Symbols on Punch-Marked Coins

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 1, Issue - 7, Sept - 2017 Shaiva symbols on Punch-Marked Coins Dr.Kanhaiya Singh Post Doctoral Fellow, Ancient history, Archaeology and culture Department, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gorakhpur University Gorakhpur. UP, India Email - [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: The study of coins is called Numismatics. Although Coins are very small in size, but he is strongly present important historical sources . The earliest coins of India is known as Punch-marked coins (Aahat mudra). We have Found various type of symbol on Punch-marked coins (Aahat mudra) as sun, Wheel, Six armed Wheel, Meru, Swastik, Fish, Flower, Trident, Nandipada, Taurine, animals and Jyamitik etc. all symbols are meaning full and he present social, Economic, Political, Religious and cultural conditions of contemporary India. In this research paper is present the only Shaiva symbols on punch-marked coins and prove the religious believers of contemporary Indian society and culture. Key words: Coinage, Iconography, Symbols, Religion, Culture. 1. INTRODUCTION: Conis are most important sources for Indian historiography. Although he is very small in size, but its interruption can solved a large problem of ‘Dark age’ in ancient Indian history. The coins of most authentic pieces of evidence and enlighten us about various aspects of the human life and culture of the people. Though the history of the study of the ancient Indian coins goes to back to 1800 AD, when Coldwell Found some coins from Coimbatore. The earliest coins of ancient india is known as Punch-Marked coins (Aahat Mudra). Remarkable that the earliest coins of india is called Punch-Marked, nominated by James prinsep1 in 1835 A.D. -

Lions Clubs International

GN1067D Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Only - (President, Secretary or Treasure) District 321 E District Club Club Name Title (Missing) District 321 E 30064 BASTI Treasurer District 321 E 31511 DEORIA President District 321 E 31511 DEORIA Secretary District 321 E 31511 DEORIA Treasurer District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL President District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL Secretary District 321 E 38880 GORAKHPUR VISHAL Treasurer District 321 E 44316 BALLIA BHRIGU President District 321 E 44316 BALLIA BHRIGU Secretary District 321 E 44316 BALLIA BHRIGU Treasurer District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR President District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR Secretary District 321 E 45215 JAUNPUR Treasurer District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA President District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA Secretary District 321 E 48896 GORAKHPUR GEETA Treasurer District 321 E 51493 AURAI CENTRAL President District 321 E 51493 AURAI CENTRAL Secretary District 321 E 51493 AURAI CENTRAL Treasurer District 321 E 52495 VARANASI EAST President District 321 E 52495 VARANASI EAST Secretary District 321 E 52495 VARANASI EAST Treasurer District 321 E 56897 SHAKTINAGAR JWALAMUKHI President District 321 E 56897 SHAKTINAGAR JWALAMUKHI Secretary District 321 E 56897 SHAKTINAGAR JWALAMUKHI Treasurer District 321 E 57063 BHADOHI CITY President District 321 E 57063 BHADOHI CITY Secretary District 321 E 57063 BHADOHI CITY Treasurer District 321 E 58521 FAIZABAD AWADH President District 321 E 58521 FAIZABAD AWADH Secretary District 321 E 58521 FAIZABAD AWADH Treasurer District -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 1974588 03

Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 1974588 03/06/2010 JAYA WATEK INDUSTRIES trading as ;JAYA WATEK INDUSTRIES INDIRA GANDHI ROAD, MONGOLPUR, BALURGHAT,PIN 733103,W.B. MANUFACTURER & MERCHANT AN INDAIN COMPANY Used Since :02/04/2007 KOLKATA PACKGE DRINKING WATER, FRUIT DRINKS AND FRUIT JUICES, SOFT DRINKS, SYRUPSAND OTHER PREPARATIONS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES 5463 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 BEY BLADER 2159631 14/06/2011 HECTOR BEVERAGES PVT. LTD B-82 SOUTH CITY -1 GURGAON 122001 SERVICE PROVIDER AN INCORPORATED COMPANY Address for service in India/Agents address: CHESTLAW H 2/4, MALVIYA NAGAR NEW DELHI-110017 Proposed to be Used DELHI BEVERAGES, NAMELY DRINKING WATERS, FLAVOURED WATERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS AND OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES, NAMELY SOFT DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, AND SPORTS DRINKS, FRUIT DRINKS AND JUICES, SYRUPS, CONCENTRATES AND POWDERS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES, NAMELY FLAVORED WATERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS, SOFT DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, SPORTS DRINKS, FRUIT DRINKS AND JUICES; DE- ALCOHOLISED DRINKS AND BEER ETC. 5464 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 PowerPop 2299749 15/03/2012 ESSEN FOODDIES INDIA PVT,LTD. trading as ;ESSEN FOODDIES INDIA PVT,LTD. KINFRA (FOOD) SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE, KAKKANCHERY,CHELEMBRA P.O., MALAPPURAM - 673634 KERALA MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS - Address for service in India/Attorney address: ANUP JOACHIM.T CC43/ 1983, SRSRA-2, SANTHIPURAM ROAD, COCHIN-682025,KERALA Proposed to be Used CHENNAI MINERAL AND AERATED WATER, NUTRITION DRINKS, ENERGY DRINKS, PACKAGED DRINKING WATER, FRUIT DRINKS AND FRUIT JUICES, SYRUPS, OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC DRINKS. 5465 Trade Marks Journal No: 1869 , 01/10/2018 Class 32 2441929 13/12/2012 HIMANSHU BHATT DHIREN BHARAD trading as ;J. -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

Bal Satsang Pariksha - Two

1 SSP / JUL 98 / 01 / 150 BOCHASANWASI SHRI AKSHARPURUSHOTTAM SWAMINARAYAN SANSTHA SATSANG SHIKSHAN PARIKSHA BAL SATSANG PARIKSHA - TWO. Date : 19th JULY 1998 Time : 9 a.m. to 11.00 a.m. Qu. Marks No. Obtained Candidate Seat No : 1. Total Marks :100 2. 3. No. of Centre :........................ 4. Name of Centre :..................... 5. Age of Candidate :................ 6. Signature of Class Supervisor................................................................ 7. NOTE : 1. Figures given on the right hand side indicate the marks 8. for that question. 9. 2. Follow the instructions while answering. 10. 3. Answers should be clear without cancellations. Good Writing Five marks will be given for clear and neat hand writing. Total Examiner’s Signature : ........................................... 01 2 Q.1 Fill in the blanks by choosing the correct answer from the words given in the brackets. 10 1. Yogiji Maharaj became a sadhu at the age of .......................... (17, 18, 19) 2. I have sacrificed myself for ......................................... (Maharaj, Gunatitanand Swami, Pramukh Swami) 3. Shantilal was initiated as parshad at ............................... (Atladra, Amdavad, Gondal) 4. Shriji Maharaj returned back the property to Dada Khachar after .......................... months. (12, 10, 6) 5. At .......................... two small boys used to come regulary for Swamishri's darshan. (Darban, Chicago, London) 6. Shriji Maharaj decided give ......................... kg of wheat to every houses in Jetalpur to grind. (30, 20, 25) 7. There is a temple of ................................. sadhu at Chansad. (Dayanandi, Ramanandi, Ramanujanandi) 8. ................................... named Mulji. (Atmanand Swami, Ramanand Swami, Muktanand Swami) 9. Mulji left home in the year ..................... .(1841, 1856, 1865) 10. The other name of Nirgunanand was ............................ (Nirvikalpanand, Gunatitanand, Nirgunswarupanand) Q.2. Answer the following in one sentence. -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust. -

MM XXVI No. 1.Pmd

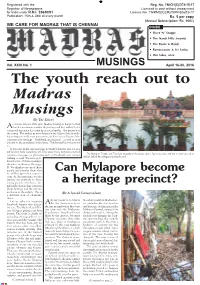

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/15-17 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/15-17 Publication: 15th & 28th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE • Short ‘N’ Snappy • The Nandi Hills Swamiji • The Ryans & Rajaji • Rameswaram & Sri Lanka • Our lakes, once Vol. XXVI No. 1 MUSINGS April 16-30, 2016 The youth reach out to Madras Musings (By The Editor) s it steps into its 26th year, Madras Musings is happy to find Athat the maximum number of greetings and best wishes for its continued existence has come in on social media – the preserve of the young. This makes us most happy for we believe that by mak- ing an impact on the next generation, we have carried forward the concerns over heritage – both built and natural – as well as over our city to the guardians of the future. This by itself is a victory for us. It was only in the last issue that we made it known that we as a publication have completed 25. Ever since then, we have received countless messages on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter The Mylapore Temple and Tank look beautiful in the picture above. But come closer and this is what you will see wishing us well. We have pub- (below) behind the railings protecting the tank. lished some of these messages elsewhere in this issue (See page 3). -

Gaudiya Math in Austria Keykey Elements of Cost for the Future, Based on the fi Nancial Support Received

Sriman Mahaprabhu and His Mission Who established the Sri Krishna Chaitanya Mission? audiya Vaishnavism is a spiritual move- e Modern Era he founder acharya of Sri After taking sannyas in 1940, He has started the Sri ment founded by Sri Krishna Chaitanya As time passed, the theology and practice of this Krishna Chaitanya Mission Krishna Chaitanya Mission in India. While preaching the Sri Sri Radha Govinda Gaudiya Math GMahaprabhu in India in the 15th century. pure devotional line were buried in ignorance and T is Om Vishnupada Srila message of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu he established 26 ‘Gaudiya’ refers to the Gaudiya region (present misconceptions. At this precarious time, in 1838 B.V. Puri Gosvami. He appeared in Gaudiya Maths in India, Italy, Spain, Mexico and Austria, day West Bengal/Bangladesh) with Vaishnavism Srila Bhaktivinoda akur was born in Birnagar in 1913 in a small village in Berham- additionally initiating thousands of disciples in the chant- NEW TEMPLE PROJECT meaning ‘ e worship of Vishnu (Krishna)’. Its the district of Nadia in West Bengal. After coming pur district, Orissa, India. After ing of the Holy Name. philosophical basis are Bhagavad Gita, Srimad in contact with the life and teachings of Sri Chait- completing his study of Ayurveda Bhagavatam as well as other puranic scriptures anya Mahaprabhu he focused all his activities on he opened a hospital and simul- Present Acharya in Austria and the Upanishads. Sri Krishna Chaitanya Ma- Sri Krishna Chaitanya the study and distribution of Mahaprabhu’s mes- taneously led Gandhi’s freedom Before he left this world he Mahaprabhu haprabhu (1486–1534) is the Yuga Avatar of Su- sage. -

Waiting List SP Pune University - OPEN Sr

Waiting List SP Pune University - OPEN Sr. Hall Appln No Final Name Category Univ board Name Marks No. Ticket No NAGARDEOLEKAR Savitribai Phule Pune 1 180616938 ECO311 OPEN 19 SIDDHI SATISH University KHARADE AKANKSHA Savitribai Phule Pune 2 180616943 ECO244 OPEN 19 RAMESH University PARAB SAMIKSHA Savitribai Phule Pune 3 180617735 ECO346 OPEN 18 SURYAKANT University SALAKE KIRAN Savitribai Phule Pune 4 180616760 ECO420 OPEN 16 JAGANNATH University GHOTANKAR SANIKA Savitribai Phule Pune 5 180618595 ECO139 OPEN 14 SATYAJIT University SHINDE HANMANT Savitribai Phule Pune 6 180617159 ECO446 OPEN 14 BALIRAM University WAKCHAURE ONKAR Savitribai Phule Pune 7 180517142 ECO515 OPEN 13 BAJIRAO University JAGADALE SAURABH Savitribai Phule Pune 8 180618797 ECO186 OPEN 12 BAPURAO University Savitribai Phule Pune 9 180619405 ECO188 JAGDALE SIDDHI ABHAY OPEN 12 University Savitribai Phule Pune 10 180616626 ECO191 JAGTAP SACHIN DILIP OPEN 12 University PADIR DHANANJAY Savitribai Phule Pune 11 180617787 ECO336 OPEN 12 SARUDAS University BHOSALE BHAGVATI Savitribai Phule Pune 12 180616280 ECO050 OPEN 11 ISHWAR University DESHMUKH ANIKET Savitribai Phule Pune 13 180608751 ECO091 OPEN 11 PRASHANT University KHANDAGALE Savitribai Phule Pune 14 180600323 ECO238 OPEN 11 PRATIBHA SAHEBRAO University THODSARE SHRIPAL Savitribai Phule Pune 15 180601950 ECO485 OPEN 11 SHAHAJI University BIRAJDAR ROHIT Savitribai Phule Pune 16 180612118 ECO059 OPEN 10 GOKUL University MUTHE BHAKTI Savitribai Phule Pune 17 180605318 ECO309 OPEN 10 BABASAHEB University Savitribai -

Faculty of Juridical Sciences

FACULTY OF JURIDICAL SCIENCES COURSE:BALLB Semester –IV SUBJECT: SOCIOLOGY-III SUBJECT CODE:BAL-401 NAME OF FACULTY: DR.SHIV KUMAR TRIPATHI Lecture-21 Varna (Hinduism) Varṇa (Sanskrit: व셍ण, romanized: varṇa), a Sanskrit word with several meanings including type, order, colour or class,[1][2] was used to refer to social classes in Hindu texts like the Manusmriti.[1][3][4] These and other Hindu texts classified the society in principle into four varnas:[1][5] Brahmins: priests, scholars and teachers. Kshatriyas: rulers, warriors and administrators. [6] Vaishyas: agriculturalists and merchants. Shudras: laborers and service providers. Communities which belong to one of the four varnas or classes are called savarna or "caste Hindus". The Dalits and tribes who do not belong to any varna were called avarna.[7][8] This quadruple division is a form of social stratification, quite different from the more nuanced system Jātis which correspond to the European term "caste".[9] The varna system is discussed in Hindu texts, and understood as idealised human callings.[10][11] The concept is generally traced to the Purusha Sukta verse of the Rig Veda. The commentary on the Varna system in the Manusmriti is oft-cited.[12] Counter to these textual classifications, many Hindu texts and doctrines question and disagree with the Varna system of social classification.[13] Etymology and origins The Sanskrit term varna is derived from the root vṛ, meaning "to cover, to envelop, count, classify consider, describe or choose" (compare vṛtra).[14] The word appears -

Unit 4 Philosophy of Buddhism

Philosophy of Buddhism UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY OF BUDDHISM Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Four Noble Truths 4.3 The Eightfold Path in Buddhism 4.4 The Doctrine of Dependent Origination (Pratitya-samutpada) 4.5 The Doctrine of Momentoriness (Kshanika-vada) 4.6 The Doctrine of Karma 4.7 The Doctrine of Non-soul (anatta) 4.8 Philosophical Schools of Buddhism 4.9 Let Us Sum Up 4.10 Key Words 4.11 Further Readings and References 4.0 OBJECTIVES This unit, the philosophy of Buddhism, introduces the main philosophical notions of Buddhism. It gives a brief and comprehensive view about the central teachings of Lord Buddha and the rich philosophical implications applied on it by his followers. This study may help the students to develop a genuine taste for Buddhism and its philosophy, which would enable them to carry out more researches and study on it. Since Buddhist philosophy gives practical suggestions for a virtuous life, this study will help one to improve the quality of his or her life and the attitude towards his or her life. 4.1 INTRODUCTION Buddhist philosophy and doctrines, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, give meaningful insights about reality and human existence. Buddha was primarily an ethical teacher rather than a philosopher. His central concern was to show man the way out of suffering and not one of constructing a philosophical theory. Therefore, Buddha’s teaching lays great emphasis on the practical matters of conduct which lead to liberation. For Buddha, the root cause of suffering is ignorance and in order to eliminate suffering we need to know the nature of existence.