Chapter 5 Conclusion the Study of “Franz Osten, Bombay Talkies And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashoke Kumar

Ashoke Kumar The boss's wife and leading actress of a leading Film Company runs off with her lead man. She is caught and taken back but not the lead man who is unceremoniously dismissed. So now the company needs a new hero. The boss decides his laboratory assistant would be the Film Company's next leading man. A bizzare film plot??? Hardly. This real life story starred the Bombay Talkies Film Company, it's boss Himansu Rai , lead actress Devika Rani and lead man Najam-ul-Hussain and last but not least its laboratory assistant Ashok Kumar. And thus began an extremely successful acting career that lasted six decades! Ashok Kumar aka Dadamoni was born Kumudlal Kunjilal Ganguly in Bhagalpur and grew up in Khandwa. He briefly studied law in Calcutta, then joined his future brother-in-law Shashadhar Mukherjee at Bombay Talkies as laboratory assistant before being made its leading man. Ashok Kumar made his debut opposite Devika Rani in Jeevan Naiya (1936) but became a well known face with Achut Kanya (1936) . Devika Rani and he did a string of films together - Izzat (1937) , Savitri (1937) , Nirmala (1938) among others but she was the bigger star and chief attraction in all those films. It was with his trio of hits opposite Leela Chitnis - Kangan (1939) , Bandhan (1940) and Jhoola (1941) that Ashok Kumar really came into his own. Going with the trend he sang his own songs and some of them like Main Ban ki Chidiya , Chal Chal re Naujawaan and Na Jaane Kidhar Aaj Meri Nao Chali Re were extremely popular! Ashok Kumar initiated a more natural style of acting compared to the prevaling style that followed theatrical trends. -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

Unit Indian Cinema

Popular Culture .UNIT INDIAN CINEMA Structure Objectives Introduction Introducing Indian Cinema 13.2.1 Era of Silent Films 13.2.2 Pre-Independence Talkies 13.2.3 Post Independence Cinema Indian Cinema as an Industry Indian Cinema : Fantasy or Reality Indian Cinema in Political Perspective Image of Hero Image of Woman Music And Dance in Indian Cinema Achievements of Indian Cinema Let Us Sum Up Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A 13.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit discusses about Indian cinema. Indian cinema has been a very powerful medium for the popular expression of India's cultural identity. After reading this Unit you will be able to: familiarize yourself with the achievements of about a hundred years of Indian cinema, trace the development of Indian cinema as an industry, spell out the various ways in which social reality has been portrayed in Indian cinema, place Indian cinema in a political perspective, define the specificities of the images of men and women in Indian cinema, . outline the importance of music in cinema, and get an idea of the main achievements of Indian cinema. 13.1 INTRODUCTION .p It is not possible to fully comprehend the various facets of modern Indan culture without understanding Indian cinema. Although primarily a source of entertainment, Indian cinema has nonetheless played an important role in carving out areas of unity between various groups and communities based on caste, religion and language. Indian cinema is almost as old as world cinema. On the one hand it has gdted to the world great film makers like Satyajit Ray, , it has also, on the other hand, evolved melodramatic forms of popular films which have gone beyond the Indian frontiers to create an impact in regions of South west Asia. -

Unit-2 Silent Era to Talkies, Cinema in Later Decades

Bachelor of Arts (Honors) in Journalism& Mass Communication (BJMC) BJMC-6 HISTORY OF THE MEDIA Block - 4 VISUAL MEDIA UNIT-1 EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA UNIT-2 SILENT ERA TO TALKIES, CINEMA IN LATER DECADES UNIT-3 COMING OF TELEVISION AND STATE’S DEVELOPMENT AGENDA UNIT-4 ARRIVAL OF TRANSNATIONAL TELEVISION; FORMATION OF PRASAR BHARATI The Course follows the UGC prescribed syllabus for BA(Honors) Journalism under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS). Course Writer Course Editor Dr. Narsingh Majhi Dr. Sudarshan Yadav Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Journalism and Mass Communication Dept. of Mass Communication, Sri Sri University, Cuttack Central University of Jharkhand Material Production Dr. Manas Ranjan Pujari Registrar Odisha State Open University, Sambalpur (CC) OSOU, JUNE 2020. VISUAL MEDIA is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-sa/4.0 Printedby: UNIT-1EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA Unit Structure 1.1. Learning Objective 1.2. Introduction 1.3. Evolution of Photography 1.4. History of Lithography 1.5. Evolution of Cinema 1.6. Check Your Progress 1.1.LEARNING OBJECTIVE After completing this unit, learners should be able to understand: the technological development of photography; the history and development of printing; and the development of the motion picture industry and technology. 1.2.INTRODUCTION Learners as you are aware that we are going to discuss the technological development of photography, lithography and motion picture. In the present times, the human society is very hard to think if the invention of photography hasn‘t been materialized. It is hard to imagine the world without photography. -

Sample Pages

Between the Studio and the World Built Sets and Outdoor Locations in the Films of Bombay Talkies ¢ Debashree Mukherjee ¢ Cinema is a form that forces us to question distinctions between the natural world and a world made by humans. Film studios manufacture natural environments with as much finesse as they fabricate built environments. Even when shooting outdoors, film crews alter and choreograph their surroundings in order to produce artful visions of nature. This historical proclivity has led theorists such as Jennifer Fay to name cinema as the “aesthetic practice of the Anthropocene,” that is, an art form that intervenes in and interferes with the natural world, mirroring humankind’s calamitous impact on the planet since the Industrial Revolution (2018, 4). In what follows, my concern is with thinking about how the indoor and the outdoor, Publishingthe world of the studio and the many worlds outside, are co-constituted through the act of filming. I am interested in how we can think of a mutual exertion of spatial influence and the co-production of space by multiple actors. Once framed by the camera, nature becomes a set of values (purity, regeneration, unpredictability), as does the city (freedom, anonymity, danger). The Wirsching collection allows us to examine these values and their construction by keeping in view both the filmed narrative as well as parafilmic images of production. By examining the physical and imaginative worlds that were manufactured in the early films of Bombay Talkies—built sets, Mapin painted backdrops, carefully calibrated outdoor locations—I pursue some meanings of “place” that unfold outwards from the film frame, and how an idea of place is critical to establishing the identity of characters. -

Download Download

Kervan – International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies n. 21 (2017) Item Girls and Objects of Dreams: Why Indian Censors Agree to Bold Scenes in Bollywood Films Tatiana Szurlej The article presents the social background, which helped Bollywood film industry to develop the so-called “item numbers”, replace them by “dream sequences”, and come back to the “item number” formula again. The songs performed by the film vamp or the character, who takes no part in the story, the musical interludes, which replaced the first way to show on the screen all elements which are theoretically banned, and the guest appearances of film stars on the screen are a very clever ways to fight all the prohibitions imposed by Indian censors. Censors found that film censorship was necessary, because the film as a medium is much more popular than literature or theater, and therefore has an impact on all people. Indeed, the viewers perceive the screen story as the world around them, so it becomes easy for them to accept the screen reality and move it to everyday life. That’s why the movie, despite the fact that even the very process of its creation is much more conventional than, for example, the theater performance, seems to be much more “real” to the audience than any story shown on the stage. Therefore, despite the fact that one of the most dangerous elements on which Indian censorship seems to be extremely sensitive is eroticism, this is also the most desired part of cinema. Moreover, filmmakers, who are tightly constrained, need at the same time to provide pleasure to the audience to get the invested money back, so they invented various tricks by which they manage to bypass censorship. -

Bombay Talkies

A Cinematic Imagination: Josef Wirsching and The Bombay Talkies Debashree Mukherjee Encounters, Exile, Belonging The story of how Josef Wirsching came to work in Bombay is fascinating and full of meandering details. In brief, it’s a story of creative confluence and, well, serendipity … the right people with the right ideas getting together at the right time. Thus, the theme of encounters – cultural, personal, intermedial – is key to understanding Josef Wirsching’s career and its significance. Born in Munich in 1903, Wirsching experienced all the cultural ferment of the interwar years. Cinema was still a fledgling art form at the time, and was radically influenced by Munich’s robust theatre and photography scene. For example, the Ostermayr brothers (Franz, Peter, Ottmarr) ran a photography studio, studied acting, and worked at Max Reinhardt’s Kammertheater before they turned wholeheartedly to filmmaking. Josef Wirsching himself was slated to take over his father’s costume and set design studios, but had a career epiphany when he was gifted a still camera on his 16th birthday. Against initial family resistance, Josef enrolled in a prestigious 1 industrial arts school to study photography and subsequently joined Weiss-Blau-Film as an apprentice photographer. By the early 1920s, Peter Ostermayr’s Emelka film company had 51 Projects / Processes become a greatly desired destination for young people wanting to make a name in cinema. Josef Wirsching joined Emelka at this time, as did another young man named Alfred Hitchcock. Back in India, at the turn of the century, Indian artists were actively trying to forge an aesthetic language that could be simultaneously nationalist as well as modern. -

DADASAHEB PHALKE AWARD for AMITABH BACHCHAN Relevant For: Pre-Specific GK | Topic: Important Prizes and Related Facts

Source : www.thehindu.com Date : 2019-09-25 DADASAHEB PHALKE AWARD FOR AMITABH BACHCHAN Relevant for: Pre-Specific GK | Topic: Important Prizes and Related Facts Amitabh Bachchan The country’s highest film honour, the Dadasaheb Phalke award, conferred for “outstanding contribution for the growth and development of Indian cinema” will be presented this year to Amitabh Bachchan. The first intimation of it came via a tweet by Information and Broadcasting Minister Prakash Javadekar in which he stated that “The legend Amitabh Bachchan who entertained and inspired for two generations has been selected unanimously for #DadaSahabPhalke award. The entire country and international community is happy. My heartiest congratulations to him. @narendramodi @SrBachchan.” Timely arrival The award, very appropriately comes in the year that marks Mr. Bachchan’s golden jubilee in cinema. He made his debut in 1969 with Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’ Saat Hindustani about seven Indians attempting to liberate Goa from Portuguese colonial rule. The same year he also did the voiceover for Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome , one of the earliest films of Indian parallel cinema. Interestingly, the Dadasaheb Phalke award itself was first presented in the year of Mr. Bachchan’s debut. It was introduced by the government in 1969 to commemorate the “father of Indian cinema” who directed Raja Harishchandra (1913), India’s first feature film, and it was awarded for the first time to Devika Rani, “the first lady of Indian cinema.” One of the most influential figures in Indian cinema for the past five decades, Mr. Bachchan, with four national awards and 15 Filmfare trophies behind him, has had a many-splendoured stint in the world of entertainment. -

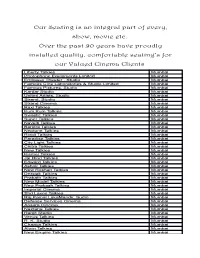

Our Seating Is an Integral Part of Every, Show, Movie Etc. Over the Past 90 Years Have Proudly Installed Quality, Comfortable Seating’S for Our Valued Cinema Clients

Our Seating is an integral part of every, show, movie etc. Over the past 90 years have proudly installed quality, comfortable seating’s for our Valued Cinema Clients Liberty Talkies Mumbai Photophone Equipments Limited Mumbai Embassy Theater , Studio Mumbai Famous Cine Laboratories & Studio Limited Mumbai Famous Pictures, Studio Mumbai Kardar Studio Mumbai United Artists, Studio Mumbai Strand, Studio Mumbai Strand Cinema Mumbai Raxi Talkies Mumbai Kum Kum Talkies Mumbai Swastic Talkies Mumbai Super Talkies Mumbai Navelti Talkies Mumbai Bandra Talkies Mumbai Neptune Talkies Mumbai Rivoli Talkies Mumbai Paradise Talkies Mumbai City Light Talkies Mumbai Chitra Talkies Mumbai New Talkies Mumbai Kismet Talkies Mumbai Jai Hind Talkies Mumbai Edward Talkies Mumbai Ashok Talkies Mumbai New Roshan Talkies Mumbai Deepak Talkies Mumbai Prabath Talkies Mumbai New Model Talkies Mumbai New Prakash Talkies Mumbai Imperial Cinema Mumbai Shri Laxmi Talkies Mumbai Raj Kamal LakaMandir, Sudio Mumbai Defense Services Cinema Mumbai Apsara Cinema Mumbai Nazrana Talkies Mumbai Ranjit Studio Mumbai Venus Talkies Mumbai R. K. Studio Mumbai Chaaya Talkies Mumbai Alwin Talkies Mumbai New Empire Talkies Mumbai Kohinoor Talkies Mumbai Usha Talkies Mumbai Surya Talkies Mumbai Bhiwandi Talkies Mumbai Roop Talkies Mumbai Royal Talkies Mumbai Bombay Theatre Mumbai Royal Opera House Mumbai Uday Talkies Mumbai Akash Talkies Mumbai Anupan Chitra Mandir Mumbai Topiwala Theatre Mumbai Vijay Talkies Mumbai Rex Cinema Mumbai Lotus Cinema Mumbai Jaya Talkies Mumbai Krishna Talkies Mumbai Krishna Talkies, Kalyan Mumbai Paramount Talkies Mumbai Oscar Cinema Mumbai Amber Cinema Mumbai Minor Cinema Mumbai Kasturba Cinema Mumbai Milap Cinemas Mumbai Sahakar Chitra Mandir Mumbai Taj Cinema Mumbai Kareer Mini Theatre Mumbai Deep Mandir Mumbai Bharat Trading Company, Exports Mumbai Anand Talkies Mumbai Gopi Chitra Mandir Mumbai Dahisar Theatres Pvt. -

Translation Today

Translation Today Editor TARIQ KHAN Volume 12, Issue 2 2018 Editor TARIQ KHAN Officer in Charge, NTM Assistant Editors Advisors GEETHAKUMARY V. D. G. RAO , Director, CIIL ABDUL HALIM C. V. SHIVARAMAKRISHNA ADITYA KUMAR PANDA Head, Centre for TS, CIIL Editorial Board SUSAN BASSNETT JEREMY MUNDAY School of Modern Languages and School of Languages, Cultures and Cultures, University of Warwick, Societies, University of Leeds, Coventry, United Kingdom Leeds, United Kingdom HARISH TRIVEDI ANTHONY PYM Department of English, Translation and Intercultural Studies, University of Delhi, The RoviraiVirgili University, New Delhi, India Tarragona, Spain MICHAEL CRONIN PANCHANAN MOHANTY School of Applied Language and Centre for Applied Linguistics and Intercultural Studies, Dublin Translation Studies, University of University, Dublin, Ireland Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India DOUGLAS ROBINSON AVADHESH KUMAR SINGH Department of English, School of Translation Studies and Hong Kong Baptist University, Training, Indira Gandhi National Open Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong University, New Delhi, India SHERRY SIMON SUSHANT KUMAR MISHRA Department of French, Centre of French and Francophone Concordia University, Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Quebec, Canada New Delhi, India Translation Today Volume 12, Issue 2, 2018 Web Address: http://www.ntm.org.in/languages/english/translationtoday.aspx Editor : TARIQ KHAN E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] © National Translation Mission, CIIL, Mysuru, 2018. This material may not be reproduced -

Saadat Hasan Manto Ashok Kumar

Ashok Kumar A Najmul Hasan made off with Devika Rani, Bombay Talkies was thrown into complete chaos. Filming had started, a few scenes had even been finished when Najmul Hasan pulled his heroine from the world of celluloid into the real world. But the person who was most distressed and worried at the Talkies was Himanshu Roy—Devika Rani’s husband and the behind-the-scenes brains of the company. In those days S. Mukherjee, brother-in-law of Ashok Kumar and the well-known filmmaker of many popular movies, was an assistant to Mr. Savak Vacha, the sound engineer at the Talkies. Being a Bengali himself he naturally felt for Himanshu Roy. Somehow or other he wanted Devika Rani to come back. So, without consulting Himanshu Roy, he made some efforts on his own and, by using his exceptional tact, he persuaded Devika Rani to fly from the arms of her lover back into the arms of the Talkies, which offered her talent more room to grow. And fly back she did. Then S. Mukherjee used his tact once again and prevailed upon his distraught mentor, Roy, to take her back. Poor Najmul Hasan joined the list of lovers separated from their beloveds by political, religious and capitalist intrigues. He was cut off—with a pair of scissors as it were—from the film and dumped into the wastebasket. This created a problem: who should now be cast opposite the already smitten Devika Rani as her lover on the screen? Himanshu Roy was an exceedingly hardworking filmmaker who pretty much kept to himself and remained quietly absorbed in his work. -

Bhavan's Bhagwandas Purohit Vidya Mandir Srikrishna Nagar, Wathoda , Nagpur - 440024

Bhavan's Bhagwandas Purohit Vidya Mandir Srikrishna Nagar, Wathoda , Nagpur - 440024 Collection Register for of Collection [Book], Category [0], Room [0], Shelf [0], Rack [0] Sl.No. Acc. Code Acc. Date Title Author Publisher Pub. Year Call No. Withdrawn No Withdrawn Dt. 1 BOK1 03/07/1995 Adventure at the Castle - MURRAY , WILLIAM Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1995 823/ TOU-AMUR Key Words Reading Scheme - 10 b 2 BOK2 03/07/1995 Sleeping Beauty - Read It AINSWORTH , ALISON Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1993 823/TOU-SAIN Yourself 3 BOK3 03/07/1995 Out In the Sun - Key Words MURRAY , WILLIAM Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1995 823 / TOU-OMUR Reading Scheme - 5 b 4 BOK4 03/07/1995 We Like To Help - Key MURRAY , WILLIAM Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1995 823 / TOU-WMUR Words Reading Scheme - 6 b 5 BOK5 03/07/1995 Things We Do - Key Words MURRAY , WILLIAM Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1995 823 /TOU-TMUR Reading Scheme - 4 a 6 BOK6 03/07/1995 Thumbelina - Read It AINSWORTH , ALISON Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1993 823/TOU-TAIN Yourself 7 BOK7 03/07/1995 PUSS IN BOOTS - READ HUNIA , FRAN Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1993 823/TOU-PHUN IT YOURSELF 8 BOK8 03/07/1995 THINGS WE DO Touche , De La Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1995 823/TOU-TTOU 9 BOK9 03/07/1995 THE GINGERBREAD HUNIA , FRAN Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1993 823/TOU-GHUN MAN - READ IT YOURSELF 10 BOK10 03/07/1995 GOLDILOCKS AND THE HUNIA , FRAN Ladybird Books Ltd.. 1993 823 / TOU-GHUN THREE BEARS - READ IT YOURSELF 11 BOK11 03/07/1995 THE THREE LITTLE HUNIA , FRAN Ladybird Books Ltd.