Saadat Hasan Manto Ashok Kumar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

Ashoke Kumar

Ashoke Kumar The boss's wife and leading actress of a leading Film Company runs off with her lead man. She is caught and taken back but not the lead man who is unceremoniously dismissed. So now the company needs a new hero. The boss decides his laboratory assistant would be the Film Company's next leading man. A bizzare film plot??? Hardly. This real life story starred the Bombay Talkies Film Company, it's boss Himansu Rai , lead actress Devika Rani and lead man Najam-ul-Hussain and last but not least its laboratory assistant Ashok Kumar. And thus began an extremely successful acting career that lasted six decades! Ashok Kumar aka Dadamoni was born Kumudlal Kunjilal Ganguly in Bhagalpur and grew up in Khandwa. He briefly studied law in Calcutta, then joined his future brother-in-law Shashadhar Mukherjee at Bombay Talkies as laboratory assistant before being made its leading man. Ashok Kumar made his debut opposite Devika Rani in Jeevan Naiya (1936) but became a well known face with Achut Kanya (1936) . Devika Rani and he did a string of films together - Izzat (1937) , Savitri (1937) , Nirmala (1938) among others but she was the bigger star and chief attraction in all those films. It was with his trio of hits opposite Leela Chitnis - Kangan (1939) , Bandhan (1940) and Jhoola (1941) that Ashok Kumar really came into his own. Going with the trend he sang his own songs and some of them like Main Ban ki Chidiya , Chal Chal re Naujawaan and Na Jaane Kidhar Aaj Meri Nao Chali Re were extremely popular! Ashok Kumar initiated a more natural style of acting compared to the prevaling style that followed theatrical trends. -

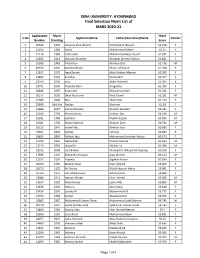

Final List MBBS.Xlsx

Final Selection Merit List of MBBS 2020-21 Application Merit Merit S.No Applicant Name Father/Guardian/Name Gender Number Standing Score 1 30524 2256 Vaneeza Khan Bhand Rehmatullah Bhand 62.218 F 2 31242 2289 Salwa Muhammad Saleem 62.15 F 3 22118 2384 Aisha Jatoi Muhammad Baqir Yousif 61.941 F 4 22645 2413 Warisha Waseem Waseem Ahmed Chohan 61.841 F 5 26993 2449 Irfan Khan Ali Khan Shar 61.736 M 6 20539 2453 Ramsha Shams Shams Ul Haque 61.736 F 7 12657 2507 Aqsa Zareen Abdul Hafeez Memon 61.595 F 8 32822 2554 Sandhya Parshotam 61.477 F 9 22949 2590 Iqra Abdul Waheed 61.364 F 10 24731 2594 Priyanka Devi Durga Das 61.355 F 11 26844 2597 Eman Asif Muhammad Asif 61.345 F 12 28577 2620 Dhan Raj Kumar Reva Chand 61.291 M 13 32385 2640 Ritu Tikam Das 61.223 F 14 25690 Add.List Hadiqa Khurram 61.18 F 15 32968 2697 Kainat Mustafa Ghulam Mustafa 61.041 F 16 21240 2704 Manoj Kumar Kishwar Das 61.018 M 17 19031 2760 Saifullah Khalid Hussain 60.873 M 18 24566 2796 Rizwan Ahmed Ghulam Zakir 60.791 M 19 20213 2844 Kashaf Naz Ghafoor Bux 60.686 F 20 18302 2846 Mehak Lal Dino 60.682 F 21 29855 2895 Rafidah Iqra Mohammad Jamshed Akhtar 60.573 F 22 22744 2961 Habibullah Muhammad Ali 60.432 M 23 12710 2982 Jawad Ali Akhtiar Ali 60.386 M 24 19252 3038 Laraib Noor Shaheed Dr Wilayat Ali Gopang 60.259 F 25 17996 3115 Shabeeh Ul Hassan Aijaz Ahmed 60.114 M 26 12734 3156 Yogeeta Jagdesh Kumar 60.036 F 27 26059 3165 Moatar Nisar Nisar Ahmed 60.009 F 28 16273 3172 Ali Fatima Khalid Hussain Hakro 59.991 F 29 19760 3175 Juhi Maheshwari Ashok Kumar 59.982 F 30 16080 -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

Unit Indian Cinema

Popular Culture .UNIT INDIAN CINEMA Structure Objectives Introduction Introducing Indian Cinema 13.2.1 Era of Silent Films 13.2.2 Pre-Independence Talkies 13.2.3 Post Independence Cinema Indian Cinema as an Industry Indian Cinema : Fantasy or Reality Indian Cinema in Political Perspective Image of Hero Image of Woman Music And Dance in Indian Cinema Achievements of Indian Cinema Let Us Sum Up Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A 13.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit discusses about Indian cinema. Indian cinema has been a very powerful medium for the popular expression of India's cultural identity. After reading this Unit you will be able to: familiarize yourself with the achievements of about a hundred years of Indian cinema, trace the development of Indian cinema as an industry, spell out the various ways in which social reality has been portrayed in Indian cinema, place Indian cinema in a political perspective, define the specificities of the images of men and women in Indian cinema, . outline the importance of music in cinema, and get an idea of the main achievements of Indian cinema. 13.1 INTRODUCTION .p It is not possible to fully comprehend the various facets of modern Indan culture without understanding Indian cinema. Although primarily a source of entertainment, Indian cinema has nonetheless played an important role in carving out areas of unity between various groups and communities based on caste, religion and language. Indian cinema is almost as old as world cinema. On the one hand it has gdted to the world great film makers like Satyajit Ray, , it has also, on the other hand, evolved melodramatic forms of popular films which have gone beyond the Indian frontiers to create an impact in regions of South west Asia. -

Unit-2 Silent Era to Talkies, Cinema in Later Decades

Bachelor of Arts (Honors) in Journalism& Mass Communication (BJMC) BJMC-6 HISTORY OF THE MEDIA Block - 4 VISUAL MEDIA UNIT-1 EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA UNIT-2 SILENT ERA TO TALKIES, CINEMA IN LATER DECADES UNIT-3 COMING OF TELEVISION AND STATE’S DEVELOPMENT AGENDA UNIT-4 ARRIVAL OF TRANSNATIONAL TELEVISION; FORMATION OF PRASAR BHARATI The Course follows the UGC prescribed syllabus for BA(Honors) Journalism under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS). Course Writer Course Editor Dr. Narsingh Majhi Dr. Sudarshan Yadav Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Journalism and Mass Communication Dept. of Mass Communication, Sri Sri University, Cuttack Central University of Jharkhand Material Production Dr. Manas Ranjan Pujari Registrar Odisha State Open University, Sambalpur (CC) OSOU, JUNE 2020. VISUAL MEDIA is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-sa/4.0 Printedby: UNIT-1EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA Unit Structure 1.1. Learning Objective 1.2. Introduction 1.3. Evolution of Photography 1.4. History of Lithography 1.5. Evolution of Cinema 1.6. Check Your Progress 1.1.LEARNING OBJECTIVE After completing this unit, learners should be able to understand: the technological development of photography; the history and development of printing; and the development of the motion picture industry and technology. 1.2.INTRODUCTION Learners as you are aware that we are going to discuss the technological development of photography, lithography and motion picture. In the present times, the human society is very hard to think if the invention of photography hasn‘t been materialized. It is hard to imagine the world without photography. -

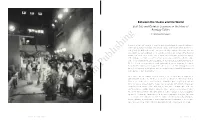

Sample Pages

Between the Studio and the World Built Sets and Outdoor Locations in the Films of Bombay Talkies ¢ Debashree Mukherjee ¢ Cinema is a form that forces us to question distinctions between the natural world and a world made by humans. Film studios manufacture natural environments with as much finesse as they fabricate built environments. Even when shooting outdoors, film crews alter and choreograph their surroundings in order to produce artful visions of nature. This historical proclivity has led theorists such as Jennifer Fay to name cinema as the “aesthetic practice of the Anthropocene,” that is, an art form that intervenes in and interferes with the natural world, mirroring humankind’s calamitous impact on the planet since the Industrial Revolution (2018, 4). In what follows, my concern is with thinking about how the indoor and the outdoor, Publishingthe world of the studio and the many worlds outside, are co-constituted through the act of filming. I am interested in how we can think of a mutual exertion of spatial influence and the co-production of space by multiple actors. Once framed by the camera, nature becomes a set of values (purity, regeneration, unpredictability), as does the city (freedom, anonymity, danger). The Wirsching collection allows us to examine these values and their construction by keeping in view both the filmed narrative as well as parafilmic images of production. By examining the physical and imaginative worlds that were manufactured in the early films of Bombay Talkies—built sets, Mapin painted backdrops, carefully calibrated outdoor locations—I pursue some meanings of “place” that unfold outwards from the film frame, and how an idea of place is critical to establishing the identity of characters. -

Download Download

Kervan – International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies n. 21 (2017) Item Girls and Objects of Dreams: Why Indian Censors Agree to Bold Scenes in Bollywood Films Tatiana Szurlej The article presents the social background, which helped Bollywood film industry to develop the so-called “item numbers”, replace them by “dream sequences”, and come back to the “item number” formula again. The songs performed by the film vamp or the character, who takes no part in the story, the musical interludes, which replaced the first way to show on the screen all elements which are theoretically banned, and the guest appearances of film stars on the screen are a very clever ways to fight all the prohibitions imposed by Indian censors. Censors found that film censorship was necessary, because the film as a medium is much more popular than literature or theater, and therefore has an impact on all people. Indeed, the viewers perceive the screen story as the world around them, so it becomes easy for them to accept the screen reality and move it to everyday life. That’s why the movie, despite the fact that even the very process of its creation is much more conventional than, for example, the theater performance, seems to be much more “real” to the audience than any story shown on the stage. Therefore, despite the fact that one of the most dangerous elements on which Indian censorship seems to be extremely sensitive is eroticism, this is also the most desired part of cinema. Moreover, filmmakers, who are tightly constrained, need at the same time to provide pleasure to the audience to get the invested money back, so they invented various tricks by which they manage to bypass censorship. -

Bombay Talkies

A Cinematic Imagination: Josef Wirsching and The Bombay Talkies Debashree Mukherjee Encounters, Exile, Belonging The story of how Josef Wirsching came to work in Bombay is fascinating and full of meandering details. In brief, it’s a story of creative confluence and, well, serendipity … the right people with the right ideas getting together at the right time. Thus, the theme of encounters – cultural, personal, intermedial – is key to understanding Josef Wirsching’s career and its significance. Born in Munich in 1903, Wirsching experienced all the cultural ferment of the interwar years. Cinema was still a fledgling art form at the time, and was radically influenced by Munich’s robust theatre and photography scene. For example, the Ostermayr brothers (Franz, Peter, Ottmarr) ran a photography studio, studied acting, and worked at Max Reinhardt’s Kammertheater before they turned wholeheartedly to filmmaking. Josef Wirsching himself was slated to take over his father’s costume and set design studios, but had a career epiphany when he was gifted a still camera on his 16th birthday. Against initial family resistance, Josef enrolled in a prestigious 1 industrial arts school to study photography and subsequently joined Weiss-Blau-Film as an apprentice photographer. By the early 1920s, Peter Ostermayr’s Emelka film company had 51 Projects / Processes become a greatly desired destination for young people wanting to make a name in cinema. Josef Wirsching joined Emelka at this time, as did another young man named Alfred Hitchcock. Back in India, at the turn of the century, Indian artists were actively trying to forge an aesthetic language that could be simultaneously nationalist as well as modern. -

DADASAHEB PHALKE AWARD for AMITABH BACHCHAN Relevant For: Pre-Specific GK | Topic: Important Prizes and Related Facts

Source : www.thehindu.com Date : 2019-09-25 DADASAHEB PHALKE AWARD FOR AMITABH BACHCHAN Relevant for: Pre-Specific GK | Topic: Important Prizes and Related Facts Amitabh Bachchan The country’s highest film honour, the Dadasaheb Phalke award, conferred for “outstanding contribution for the growth and development of Indian cinema” will be presented this year to Amitabh Bachchan. The first intimation of it came via a tweet by Information and Broadcasting Minister Prakash Javadekar in which he stated that “The legend Amitabh Bachchan who entertained and inspired for two generations has been selected unanimously for #DadaSahabPhalke award. The entire country and international community is happy. My heartiest congratulations to him. @narendramodi @SrBachchan.” Timely arrival The award, very appropriately comes in the year that marks Mr. Bachchan’s golden jubilee in cinema. He made his debut in 1969 with Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’ Saat Hindustani about seven Indians attempting to liberate Goa from Portuguese colonial rule. The same year he also did the voiceover for Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome , one of the earliest films of Indian parallel cinema. Interestingly, the Dadasaheb Phalke award itself was first presented in the year of Mr. Bachchan’s debut. It was introduced by the government in 1969 to commemorate the “father of Indian cinema” who directed Raja Harishchandra (1913), India’s first feature film, and it was awarded for the first time to Devika Rani, “the first lady of Indian cinema.” One of the most influential figures in Indian cinema for the past five decades, Mr. Bachchan, with four national awards and 15 Filmfare trophies behind him, has had a many-splendoured stint in the world of entertainment. -

BFA Entry Test Passed Candidates Result 2015-16 (Graphic Design, Textile Design, Painting)

University College of Art & Design University of the Punjab BFA Entry Test Passed Candidates Result 2015-16 (Graphic Design, Textile Design, Painting) Note: For Further information regarding the admission procedure, Kindly consult the newspaper to be published on 30th August 2015. (The University reserves the right to correct any typographical error, omission etc.) Roll # Name Father / Guardian's Name 3 Fawad Majeed Abdul Majeed 4 Isra Zia Muhammad Zil Ullah Rana 5 Amal Arif Muhammad Arif 6 Rabia Yaseen Haifz Ghulam Yaseen 7 Hamna Masood Masood Hussain Siddiqui 8 Hira Sultan Babar Sultan 10 Mahnoor Zahra Rizvi Syed Farhat Hussain 11 Aqas Amjad Amjad Ali 14 Anam Zia Mohammad Zia ul Haq 16 Haiqa Chaudhry Humayun Rasheed 17 Fatima Usman Muhammad Usman 19 Akash Faheem Muhammad Faheem 20 Muhammad Waqar Muhammad Farooq 21 Saman Imran Mumtaz Imran 24 Syed Badar Syed Altaf Hussain 25 Muhammad Rameez Saleem Muhammad Saleem 26 Sohail Afzal Muhammad Afzal 27 Fizza Raghib Raghib Ali Prepared by Admin. Officer Convener Admission Committee Principal University College of Art & Design University of the Punjab BFA Entry Test Passed Candidates Result 2015-16 (Graphic Design, Textile Design, Painting) Note: For Further information regarding the admission procedure, Kindly consult the newspaper to be published on 30th August 2015. (The University reserves the right to correct any typographical error, omission etc.) Roll # Name Father / Guardian's Name 28 Hira Amir Sarfraz Amir Sarfraz 30 Zunaira Wahab Abdul Wahab 32 Iqra Riaz Muhammad Riaz 33 Kiran Ashraf Muhammad Ashraf 34 Rimsha Rizvi Shakil ur Rahman Rizvi 35 Muhammad Yasir Altaf Hussain 36 Imran Shahid Shahid Maqbool Naz 37 Fizza Hassan Hassan Raza 38 Remsha Anwar Muhammad Anwar 39 Asia Fayyaz Fayyaz Ahmed 40 Murrad Rahim Khan Izhar Rahim Khan 41 Hooria Alam Shah Alam Zaidi 42 Zamiah Mehmood Mehmood Ahmad Khan 43 Duaa Nauman Nauman Nasir 45 Aneeka Farooqi Abdul Hannan Farooqi 46 Ameera Hasan Khan Ahmed Hassan Khan 47 Firza Razi Dar Razi ud Din Dar 48 Farhan Tufail Muhammad Tufail Prepared by Admin. -

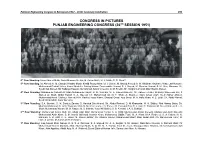

36Th Session 1951)

Pakistan Engineering Congress in Retrospect (1912 – 2012) Centenary Celebration 659 CONGRESS IN PICTURES PUNJAB ENGINEERING CONGRESS (36TH SESSION 1951) 6th Row Standing: Nisar Ahmed Malik; Abdul Mannan Sheikh; M. Aslam Mufti; M. A. Malik; R. R. Shariff 5th Row Standing: M. Ahmed; N. M. Chaudri; Mazhar Munir; Khalid Faruq Akbar; M. I. Chishti; M. Masud Ahmed; A. W. Khokhar; Mazhar-ul-Haq; Latif Hussain; Muhammad Rashid Vehra; Kamal Mustafa; Ashfaq Hasan; Ferozeuddin Ahmad; S. I. Ahmed; M. Shamim Ahmed; S. M. Niaz; Monawar Ali; Syed Irfan Ahmed; Mir Sadaqat Hassan; Muhammad Ashraf Cheema; G. M. Sheikh; Kh. Maqbool Ahmad; Mian Bashir Ahmed. 4th Row Standing: Muhammad Saadat Ali; Mian Muhammad Hayat; G. M. Subhani; M. A. Hamid Rahmani; Sh. Zahoor ul Haq; Khawaja Saleemud Din; S Ahmed Ali Shah; Abdul Hamid; S. A. Majeed; Ch. Muhammad Ali; M. T. Shah; A. Khalique; Malik Aman Ullah; Syed Iftikhar Ahmed; Muhammad Hanif; Shafique Ahmed; M A. Rashid; Fazal Karim; Shaukat Omar; Aziz Omar; M. A. Hafiz Khan; H. S. Zaidi; Ch. Abdul Hamid; Syed Mahdi Shah; Asrar Qureshy. 3rd Row Standing: S.A. Qureshi; S. M. Serajuz Zaman; S. Hamiud Din Ahmed; Sh. Abdur Rawoof; D. M Khanzada; M. H. Siddiqi; Rab Nawaz Batra; Sh. Mukhtar Mahmood; S. Jaffar Hussain; Malik N. M. Khan; Jameel A. Parvez; M. Faizanul Haq; H. J. Asar; F. Rahman: M. Saeed Ahmed; S. I. A. Shah; Muhammad Akram; M. M. Haque; M. S. Minhas; Yusuf Ali Siddiqi; S. S. Kirmani; I. A. S. Bokhari. 2nd Row Standing: Muhammad Aslam Butt; Ch. Abdul Azjz; Mian Muhammad Yunas; S.