Roshan Ara Begum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

Program Coordinators LUMS Music Fest'21 Dear Sir/Madam, the Music

To Managers/ Program Coordinators LUMS Music Fest’21 Dear Sir/Madam, The Music Society of Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) is proud to invite your institution’s musicians and non-musicians to the “LUMS Music Fest 2020 (LMF’20),” which will take place from 5th February to 7th February 2021. The Music Society of LUMS Since its inception, in 1999, the Music Society of LUMS has actively been serving as a platform for talented artists across the country to showcase their abilities. Whether it’s the students of LUMS themselves, or those from other educational institutions, we have strived to give everyone an opportunity to not only perform on stage, but also to hone their skills in doing so. We believe that the Pakistani music industry is in a critical stage of its revival, with an ever-growing audience, and a pool of talent that is expanding just as rapidly. In such promising and almost revolutionary times, the Music Society of LUMS is eager to play its part in furthering the endeavors of those before it. What is LUMS Music Fest? Music Fest is the flagship event of the Music Society of LUMS, spanning a total of three days. It is primarily a series of music-based competitions, between students from all over Pakistan, punctuated by social events to take the edge off things and of course to promote music from every genre. Over 1200 people attend Music Fest every year, whether it is the participants from a plethora of educational institutions, or the student body and faculty of LUMS itself, making it, by far the largest college-based Music Festival across the board, in Pakistan. -

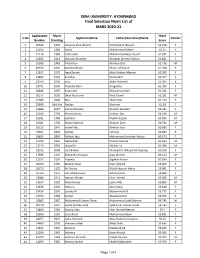

Final List MBBS.Xlsx

Final Selection Merit List of MBBS 2020-21 Application Merit Merit S.No Applicant Name Father/Guardian/Name Gender Number Standing Score 1 30524 2256 Vaneeza Khan Bhand Rehmatullah Bhand 62.218 F 2 31242 2289 Salwa Muhammad Saleem 62.15 F 3 22118 2384 Aisha Jatoi Muhammad Baqir Yousif 61.941 F 4 22645 2413 Warisha Waseem Waseem Ahmed Chohan 61.841 F 5 26993 2449 Irfan Khan Ali Khan Shar 61.736 M 6 20539 2453 Ramsha Shams Shams Ul Haque 61.736 F 7 12657 2507 Aqsa Zareen Abdul Hafeez Memon 61.595 F 8 32822 2554 Sandhya Parshotam 61.477 F 9 22949 2590 Iqra Abdul Waheed 61.364 F 10 24731 2594 Priyanka Devi Durga Das 61.355 F 11 26844 2597 Eman Asif Muhammad Asif 61.345 F 12 28577 2620 Dhan Raj Kumar Reva Chand 61.291 M 13 32385 2640 Ritu Tikam Das 61.223 F 14 25690 Add.List Hadiqa Khurram 61.18 F 15 32968 2697 Kainat Mustafa Ghulam Mustafa 61.041 F 16 21240 2704 Manoj Kumar Kishwar Das 61.018 M 17 19031 2760 Saifullah Khalid Hussain 60.873 M 18 24566 2796 Rizwan Ahmed Ghulam Zakir 60.791 M 19 20213 2844 Kashaf Naz Ghafoor Bux 60.686 F 20 18302 2846 Mehak Lal Dino 60.682 F 21 29855 2895 Rafidah Iqra Mohammad Jamshed Akhtar 60.573 F 22 22744 2961 Habibullah Muhammad Ali 60.432 M 23 12710 2982 Jawad Ali Akhtiar Ali 60.386 M 24 19252 3038 Laraib Noor Shaheed Dr Wilayat Ali Gopang 60.259 F 25 17996 3115 Shabeeh Ul Hassan Aijaz Ahmed 60.114 M 26 12734 3156 Yogeeta Jagdesh Kumar 60.036 F 27 26059 3165 Moatar Nisar Nisar Ahmed 60.009 F 28 16273 3172 Ali Fatima Khalid Hussain Hakro 59.991 F 29 19760 3175 Juhi Maheshwari Ashok Kumar 59.982 F 30 16080 -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

PADMA OIL COMPANY LIMITED Unclaimed Dividend As at 30Th June 2021

PADMA OIL COMPANY LIMITED Unclaimed Dividend as at 30th June 2021 Folio/BO No Folio/BO Name Father's Name Financial Net Dividend Year Amount (BDT) 00003 MR. A.M.M.RAFIQUE UDDIN 2017 925.65 00004 MR. A.T.M.FARIDUDDIN AHMAD 2017 925.65 00011 MR. SHAIK AHMED 2017 925.65 00017 MR. MUJIBUR RAHMAN 2017 3,543.65 00026 MR.ANWARUDDIN AHMED & 2017 7,302.35 00028 MR. RUHUL AMIN 2017 7,302.35 00039 MR. MUKBUL AHMED 2017 36,736.15 00070 MR. NOWSHA MEAH 2017 364.65 00071 MR. MD. TABARAKULLAH 2017 364.65 00072 MR. MD. FAIZ AHMED FAIZ 2017 364.65 00078 MR. SIS ESSOF GULAM MOHAMED 2017 925.65 00082 MR. MADHU SUDAN SEN 2017 364.65 00094 MR. DEEN MOHAMMED 2017 1,673.65 00095 MR. FAKIR CHAND 2017 1,673.65 00101 MR. MD. SAHABUDDIN 2017 3,543.65 00107 MR. MD. DILWAR AHMED 2017 130.90 00108 MR. MD. TOFAZZAL HOSSAIN 2017 3,543.65 00110 MR. ALAMGIR MOHAMMED KAMA LUDDIN & 2017 3,543.65 00113 MR. MD. NURUL ALAM MEAH 2017 3,543.65 00114 MR. SUKUMAR DHAR 2017 3,543.65 00115 MRS. NUR BANU KARIMUNNESA BEGUM 2017 3,543.65 00126 MR. KALA MEAH 2017 3,543.65 00127 MRS. LAL BANU 2017 3,543.65 00128 MR. MOHAMMAD IBRAHIM 2017 3,543.65 00133 MR. SK. MD. NIZAM 2017 3,543.65 00138 MR. ABDUL HAKAM 2017 5,413.65 00140 MR. IQBALUR RAHMAN 2017 10,668.35 00152 MR. MD. YOUSUF 2017 7,302.35 00162 MR. -

LIST of MEDIA RIGHTS VIOLATIONS by JOURNALIST SAFETY INDICATES (JSIS), MAY 2018 to APRIL 2019 the Media Violations Are Categorised by the Journalist Safety Indicators

74 IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2018–2019 LIST OF MEDIA RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY JOURNALIST SAFETY INDICATES (JSIS), MAY 2018 TO APRIL 2019 The media violations are categorised by the Journalist Safety Indicators. Other notable incidents are media violations recorded by the IFJ in its violation mapping. *Other notable incidents are media violations recorded by the IFJ. These are violations that fall outside the JSIs and are included in IFJ mapping on the South Asia Media Solidarity Network (SAMSN) Hub - samsn.ifj.org Afghanistan, was killed in an attack on the Sayeed Ali ina Zafari, political programs operator police chief of Kandahar, General Abdul Raziq. on Wolesi Jerga TV; and a Wolesi Jerga TV driver AFGHANISTAN The Taliban-claimed attack took place in the were entering the MOFA road for an interview in governor’s compound during a high-level official Zanbaq square when they were confronted by a JOURNALIST KILLINGS: 12 (Journalists: 5, meeting. Angar, along with others, was killed in policeman. Media staff: 7. Male: 12, Female: 0) the cross-fire. THREATS AGAINST THE LIVES OF June 5, 2018: Takhar JOURNALISTS: 8 December 4, 2018: Nangarhar Milli TV Takhar province reporter Merajuddin OTHER THREATS TO JOURNALISTS: Engineer Zalmay, director and owner or Enikass Sharifi was beaten up by the head of the None recorded radio and TV stations was kidnapped at 5pm community after a verbal disagreement. NON-FATAL ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS: during a shopping trip. He was taken by armed 61 (Journalists: 52; Media staff: 9) men who arrived in an armoured vehicle. His June 11, 2018, Ghor THREATS AGAINST MEDIA INSTITUTIONS: 3 driver was shot and taken to hospital where he Saam Weekly Director, Nadeem Ghori, had his ATTACKS ON MEDIA INSTITUTIONS: 3 later died. -

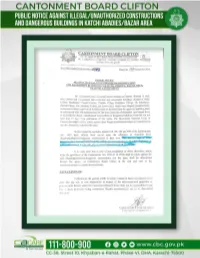

Public Notice Against Illegal / Unauthorized Constructions

CANTONMENT BOARD CLIFTON CC-38, Street 10, Kh-e-Rahat, Phase-VI, DHA, Karachi-75500 Ph. # 35847831-2, 35348774-5, 35850403, 35348784, Fax 5847835 Website: www.cbc.gov.pk _____________________________________ No. CBC/Lands/Publication/012/ Dated the 16 December 2020. PUBLIC NOTICE AGAINST ILLEGAL/UNAUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION AND DANGEROUS BUILDINGS IN KATCHI ABADIES/BAZAR AREA CLIFTON CANTONMENT All concerned/owners/occupants/lessees/tenants are hereby directed in their own interest and convenience that residential and commercial buildings situated at Delhi Colony, Madniabad, Punjab Colony, Chandio Village, Bukhshan Village, Ch. Khaliq-uz-Zaman Colony, Pak Jamhoria Colony and Lower Gizri, which were illegally/unauthorizedly constructed without approval of building plans or deviated from the approved building plans or constructed with sub- standard material and may cause loss of properties and human lives, to demolish the illegal, unauthorized constructions or dangerous buildings forthwith but not later than 15 days from publication of this notice. The Honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken serious notice against these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions and also directed to demolish the same. In this regard the requisites notices U/S 126, 185 and 256 of the Cantonments Act, 1924 have already been served upon the offenders to demolish these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions at their own. The details of such properties are as under:- DEHLI COLONY NO.01 S. Property Name of present owner Violation/ status of Name of original Lessee No. No. as per record of CBC illegal construction 1 A-01/01 Mr. Noor Bat Khan Mrs. Abida Noor Ground + 7th Floor 2 A-01/02 Mr. -

RESULT of ENTRANCE TEST for ADMISSION to PRIVATE and PUBLIC SECTOR MEDICAL and DENTAL COLLEGES 2011 ID No

RESULT OF ENTRANCE TEST FOR ADMISSION TO PRIVATE AND PUBLIC SECTOR MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGES 2011 ID No. NAME FATHER NAME MARKS 00001 KARESHMA WALI SHER WALI 116 00002 KASHIF ULLAH HAKEEM KHAN 194 00003 MUHAMMAD NAEEM MUHAMMED ILYAS 88 00004 TAZA GUL JANAN KHAN 394 00005 SHEEMA IQBAL MUHAMMAD IQBAL 30 00006 AMIR JAMAL NOOR JAMAL 73 00007 GOHAR JAMAL NOOR JAMAL 35 00008 RAHEEL ZAMAN SHAH ZAMAN 437 00009 SAMRINA KHAN PROF. DR. AMIR KHAN 189 00010 SIKANDAR IQBAL MUHAMMAD TAHIR 320 00011 MEHRUNISA KHAN KHALIL AURANGZEB KHAN KHALIL 395 00012 KARIM ULLAH SARFARAZ KHAN 244 00013 SUMAYYA SADIQ HAJI SADIQ SHAH 221 00014 SYED SEBGHAT ULLAH SAHIBZADA 123 00015 NAZISH YOUSAF YOUSAF ALI 120 00016 NAILA IJAZ IJAZ HUSSAIN 273 00017 NADIA ZAIB JEHAN ZAIB KHAN 75 00018 MAHREEN GOHAR GOHAR DIN 115 00019 ANAM ULLAH MUZAMMIL KHAN 419 00020 MARIA NIZAM NIZAM UD DIN 360 00021 MUJHAMMAD BASIT MUSHTAQ HUSSAIN 378 00022 UZMA MUSHRAZULLAH 89 00023 IJAZ ULLAH BAKHT SULTAN 27 00024 HAMID KHAN MUHAMMAD AFZAL 367 00025 ANEES KHAN MUHAMMAD KHAN 187 00026 ASIF KAMAL ABDUL MAJEEB 436 00027 ASIF ULLAH FAIZ ULLAH 70 00028 UMAR HAYAT BAKHTAWAR SHAH 429 00029 SHEHZADI UMBREEN EID BADSHAH 232 00030 BILAL AHMAD YAR MUHAMMAD 79 00031 SAMEERA TAJ BAHADAR 202 00032 AMJAD HAMEED ABDUL HAMEED KHAN 20 00033 ZEESHAN KAMIL KHAN 232 00034 NAJMUL ALAM SHAH DAD KHAN 228 00035 ALMAS RANI NABI REHMAT 314 00036 IQRA NAWAZ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ 344 00037 MUHAMMAD ASAD ALI SHAUKAT ALI 218 00038 AYESHA ZAIB JEHANZAIB 424 00039 IZHAR UL HAQ GUL SALAM KHAN 104 00040 MIDRARULLAH KHAN MOHAMMAD ALI -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Shareholders Without CNIC.PDF

Gharibwal Cement Limited DETAIL OF WITHOUT CNIC SHAREHOLDERS S.No. Folio Name Address Current Net Dividend shareholding (Net of Zakat and Balance tax) 1 1 HAJI AMIR UMAR C/O.HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR COTTON MERCHANT,3RD FLOOR COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG, MCLEOD ROAD, P.O.BOX.NO.4124 586 KARACHI 578 2 3 MR.MAHBOOB AHMAD MOTI MANSION, MCLEOD ROAD, LAHORE. 11 11 3 11 MRS.FAUZIA MUGHIS 25-TIPU SULTAN ROAD MULTAN CANTT 1,287 1,271 4 19 MALIK MOHAMMAD TARIQ C/O.MALIK KHUDA BUX SECRETARY AGRICULTURE (WEST PAKISTAN), LAHORE. 110 108 5 20 MR. NABI AHMED CHAUDHRI, C/O, MODERN MOTORS LTD, VOLKSWAGEN HOUSE, P.O.BOX NO.8505, BEAUMONT ROAD, KARACHI.4. 2,193 2,166 6 24 BEGUM INAYAT NASIR AHMED 134 C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 67 66 7 26 MRS. AMTUR RAUF AHMED, 14/11 STREET 20, KHAYABAN-E-TAUHEED, PHASE V,DEFENCE, KARACHI. 474 468 8 27 MRS.AMTUL QAYYUM AHMED 134-C MODEL TOWN LAHORE 26 25 9 31 MR.ANEES AHMED C/O.DR.GHULAM RASUL CHEEMA BHAWANA BAZAR, FAISALABAD 649 642 10 36 MST.RAFIA KHANUM C/O.MIAN MAQSOOD A.SHEIKH M/S.MAQBOOL CO.LTD ILAMA IQBAL ROAD, LAHORE. 1,789 1,767 11 37 MST.ABIDA BEGUM C/O HAJI KHUDA BUX AMIR UMAR 3RD FLOOR. COTTON EXCHANGE BUILDING, 1.1.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD, KARACHI. 2,572 2,540 12 39 MST.SAKINA BEGUM F-105 BLOCK-F ALLAMA RASHID TURABI ROAD NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2,657 2,625 13 42 MST.RAZIA BEGUM C/O M/S SADIQ SIDDIQUE CO., 32-COTTON EXCHANGE BLDG., I.I.CHUNDRIGAR ROAD KARACHI. -

A Nonlinear Study on Time Evolution in Gharana

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC Archi Banerjee1,2*, Shankha Sanyal1,2*, Ranjan Sengupta2 and Dipak Ghosh2 1 Department of Physics, Jadavpur University 2 Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 India *[email protected] * Corresponding author Archi Banerjee: [email protected] Shankha Sanyal: [email protected]* Ranjan Sengupta: [email protected] Dipak Ghosh: [email protected] © 2019 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC ABSTRACT Indian classical music is entirely based on the “Raga” structures. In Indian classical music, a “Gharana” or school refers to the adherence of a group of musicians to a particular musical style of performing a raga. The objective of this work was to find out if any characteristic acoustic cues exist which discriminates a particular gharana from the other. Another intriguing fact is if the artists of the same gharana keep their singing style unchanged over generations or evolution of music takes place like everything else in nature. In this work, we chose to study the similarities and differences in singing style of some artists from at least four consecutive generations representing four different gharanas using robust non-linear methods. For this, alap parts of a particular raga sung by all the artists were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA and MFDXA) technique. -

Bhimsen Joshi and the Kirana Gharana«

Bhimsen Joshi and the Kirana Gharana« CHETAN KARNAN! I. INTRODUCIlON he Kirana ghariinii laid emphasis on melody rather than rhythm. In our times, Bhimsen Joshi has become the most popular artist of this gharana Tbecause he combines melody with vinuosity. His teacherSawaiGandharva combined melody with the euphony of his voice. Sawai Gandharva's teacher. Abdul Karim Khan, was a pioneer and the founder of the Kiranagharana. He had arare gift for making melodic phrases in any raga he chose to sing. Abdul Karim Khan had another notable disciple in Roshan Ara Begam, but Sawai Gandharva was by far his most distinguished disciple. Sawai Gandharva's important disciples are Bhimsen Joshi, Gangubai Hangal and Firoz Dastur. In later sections of this chapter I have emphasized the rugged masculinityof GangubaiHangal's voice. I have also discussed the systematic elaboration of ragas presentedby Firoz Dastur. Just as the Gwalior gharana has two lines represented by Haddu Khan and Hassu Khan, the Kirana gharana has two lines represented by Abdul Karim Khan and Abdul Wahid Khan. Abdul Wahid Khan combined melody with systematic elaboration of raga. He laid emphasis on the placid flow of music and preferred tosing in Jhoomra tala offourteen beats. By elaboratinga raga in slow tempo, he showed a facet of melody distinct from Abdul Karim Khan. His most di stinguished disciples were Hirabai Barodekar and Pran Nath, who sang with euphony in slow tempo. It is sheer good luck that the pioneers of the Kirana gharana, Abdul Karim Khan and Abdul Wahid Khan, were saved from oblivion by the gramophone COmpanies.