Computers and Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Research Universal Communication Communication of Selling the Narrow Column Square Span Text in Color Change of Impact New Slaves

VISUAL RESEARCH UNIVERSAL COMMUNICATION COMMUNICATION OF SELLING THE NARROW COLUMN SQUARE SPAN TEXT IN COLOR CHANGE OF IMPACT NEW SLAVES ON TYPOGRAPHY by Herbert Bayer Typography is a service art, not a fine art, however pure and elemental the discipline may be. The graphic designer today seems to feel that the typographic means at his disposal have been exhausted. Accelerated by the speed of our time, a wish for new excitement is in the air. “New styles” are hopefully expected to appear. Nothing is more constructive than to look the facts in the face. What are they? The fact that nothing new has developed in recent decades? The boredom of the dead end without signs for a renewal? Or is it the realization that a forced change in search of a “new style” can only bring superficial gain? It seems appropriate at this point to recall the essence of statements made by progressive typographers of the 1920s: Previously used largely as a medium for making language visible, typographic material was discovered to have distinctive optical properties of its own, pointing toward specifically typographic expression. Typographers envisioned possibilities of deeper visual experiences from a new exploitation of the typographic material itself. Typography was for the first time seen not as an isolated discipline and technique, but in context with the ever-widening visual experiences that the picture symbol, photo, film, and television brought. They called for clarity, conciseness, precision; for more articulation, contrast, tension in the color and black and white values of the typographic page. They recognized that in all human endeavors a technology had adjusted to man’s demands; while no marked change or improvement had taken place in man’s most profound invention, printing-writing, since Gutenberg. -

Smooth Writing with In-Line Formatting Louise S

NESUG 2007 Posters Smooth Writing with In-Line Formatting Louise S. Hadden, Abt Associates Inc., Cambridge, MA ABSTRACT PROC TEMPLATE and ODS provide SAS® programmers with the tools to create customized reports and tables that can be used multiple times, for multiple projects. For ad hoc reporting or the exploratory or design phase of creating custom reports and tables, SAS® provides us with an easy option: in-line formatting. There will be a greater range of in-line formatting available in SAS 9.2, but the technique is still useful today in SAS versions 8.2 and 9.1, in a variety of procedures and output destinations. Several examples of in-line formatting will be presented, including formatting titles, footnotes and specific cells, bolding specified lines, shading specified lines, and publishing with a custom font. INTRODUCTION In-line formatting within procedural output is generally limited to three procedures: PROC PRINT, PROC REPORT and PROC TABULATE. The exception to this rule is in-line formatting with the use of ODS ESCAPECHAR, which will be briefly discussed in this paper. Even without the use of ODSESCAPECHAR, the number of options with in- line formatting is still exciting and almost overwhelming. As I was preparing to write this paper, I found that I kept thinking of more ways to customize output than would be possible to explore at any given time. The scope of the paper therefore will be limited to a few examples outputting to two destination “families”, ODS PRINTER (RTF and PDF) and ODS HTML (HTML4). The examples presented are produced using SAS 9.1.3 (SP4) on a Microsoft XP operating system. -

Multimedia Foundations Glossary of Terms Chapter 5 – Page Layout

Multimedia Foundations Glossary of Terms Chapter 5 – Page Layout Body Copy The main text of a published document or advertisement. Border A visible outline or stroke denoting the outer frame of a design element such as a table cell, text box, or graphic. A border’s width and style can vary according to the aesthetic needs or preferences of the designer. Box Model Or CSS Box Model. A layout and design convention used in CSS for wrapping HTML text and images in a definable box consisting of: margins, borders, and padding. Cell The editable region of a data table or grid defined by the intersection of a row and column. Chunking The visual consolidation of related sentences or ideas into small blocks of information that can be quickly and easily digested (e.g. paragraphs, lists, callouts, text boxes, etc.). Column The vertically aligned cells in a data table or grid. Dynamic Page A multimedia page with content that changes (often) over time or with each individual viewing experience. F-Layout A layout design where the reader’s gaze is directed through the page in a pattern that resembles the letter F. Fixed Layout A multimedia layout where the width of the page (or wrapper) is constrained to a predetermined width and/or height. Floating Graphic The layout of a graphic on a page whereby the adjacent text wraps around it to the left and/or right. Fluid Layout Or liquid layout. A multimedia layout where the width of the page (or wrapper) is set to a percentage of the current user’s browser window size. -

Ocr: a Statistical Model of Multi-Engine Ocr Systems

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2004 Ocr: A Statistical Model Of Multi-engine Ocr Systems Mercedes Terre McDonald University of Central Florida Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation McDonald, Mercedes Terre, "Ocr: A Statistical Model Of Multi-engine Ocr Systems" (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 38. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/38 OCR: A STATISTICAL MODEL OF MULTI-ENGINE OCR SYSTEMS by MERCEDES TERRE ROGERS B.S. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in the College of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2004 ABSTRACT This thesis is a benchmark performed on three commercial Optical Character Recognition (OCR) engines. The purpose of this benchmark is to characterize the performance of the OCR engines with emphasis on the correlation of errors between each engine. The benchmarks are performed for the evaluation of the effect of a multi-OCR system employing a voting scheme to increase overall recognition accuracy. This is desirable since currently OCR systems are still unable to recognize characters with 100% accuracy. -

2010 Type Quiz

Text TypeCon 2010 Typographic Quiz Here’s How It Works 30+ Questions to Test Your Typographic Smarts Divided Into Two Parts Part One • 12 Questions (OK, 17) • First right answer to each question wins a prize • Your proctor is the arbiter of answer correctness Part Two • 18 Questions • Answers should be put on “quiz” sheets • Every correct answer to a multiple part question counts as a point • 33 Possible right answers What’s it worth? • There are the bragging rights... • How about the the Grand Prize of the complete Monotype OpenType Library of over 1000 fonts? There’s More... • Something special from FontShop • Gimme hats from Font Bureau • Industrial strength prizes from House Industries • TDC annual complements of the TDC And Even More... • Posters from Hamilton Wood Type Museum • Complete OpenType Font families from Fonts.com • Books from Mark Batty Publisher • Fantastic stuff from P22 And Even More... • Fonts & books & lots of great things from Linotype • Great Prizes from Veer – including the very desirable “Kern” sweatshirt • Font packs and comics from Active Images Over 80 prizes Just about everyone can win something Some great companies • Active Images • Font Bureau • Font Shop • Hamilton Wood Type Museum • House Industries • Linotype • Mark Batty Publisher • Monotype Imaging • P22 • Type Directors Club • Veer Awards • Typophile of the Year • The Doyald Young Typographic Powerhouse Award • The Fred Goudy Honorable Mention • Typographer’s Apprentice (Nice Try) • Typographically Challenged Note: we’re in L.A., so some questions may -

Draft Student Name: Teacher

Draft Student Name: ______________________ Teacher: ______________________ Date: ___________ District: Johnston Assessment: 9_12 Business and IT BM10 - Microsoft Word and PowerPoint Test 1 Description: Quiz 3 Form: 501 Draft 1. What is the process of changing the way characters appear, both on screen and in print, to improve document readability? A. Text formatting B. Paragraph formatting C. Character formatting D. Document formatting 2. To make text appear in a smaller font size below the middle point of the line, which character formatting effect is applied? A. Superscript B. Strikethrough C. Subscript D. Italic 3. In Microsoft Word, what is the name of the group formatting characteristics called? A. Style B. Effects C. Cluster D. Group 4. Which option on the Apply Styles dialog box changes the settings for a selected style? A. Change Styles B. Edit C. Modify D. New Style 5. How are different underline styles selected when applying the underline font format to selected text? A. Choose the Underline drop-down arrow on the Home Ribbon to select various underline styles B. Right-click underlined text and choose underline styles from the Shortcut Menu C. Select the underlined text, then choose Underline Styles from the Insert Ribbon D. Double-click underlined text and choose Underline Styles from the Shortcut Menu 6. Which command on the Home Ribbon applies a shadow, glow, or reflection to selected text or paragraphs? A. Text Effects B. Text Highlight Color C. Shading D. Color 7. Which command on the Home Ribbon allows a user to change the case of selected text to all uppercase, lowercase, sentence case, toggle case, or capitalize each word? A. -

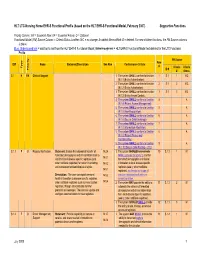

HL7 LTC-Nursing Home EHR-S Functional Profile (Based on the HL7 EHR-S Functional Model, February 2007) Supportive Functions

HL7 LTC-Nursing Home EHR-S Functional Profile (based on the HL7 EHR-S Functional Model, February 2007) Supportive Functions Priority Column: EN = Essential Now; EF = Essential Future; O = Optional Functional Model (FM) Source Column -- Criteria Status is either: N/C = no change; A=added; M=modified; D = deleted. For new children functions, the FM Source columns is blank. Blue, Underscored text = addition to text from the HL7 EHR-S Functional Model; Strikethrough text = HL7 EHR-S Functional Model text deleted for the LTC Functional Profile FM Source Row ID# Name Statement/Description See Also Conformance Criteria # Type Criteria Criteria Priority ID # # Status S.1 H EN Clinical Support 1. The system SHALL conform to function 1 S.1 1 N/C IN.1.1 (Entity Authentication). 2. The system SHALL conform to function 2 S.1 2 N/C IN.1.2 (Entity Authorization). 3. The system SHALL conform to function 3 S.1 3 N/C IN.1.3 (Entity Access Control). 4. The system SHALL conform to function 4 A IN.1.4 (Patient Access Management) 5. The system SHALL conform to function 5 A IN.1.5 (Non-Repudiation) 6. The system SHALL conform to function 6 A IN.1.6 (Secure Data Exchange) 7. The system SHALL conform to function 7 A IN.1.8 (Information Attestation) 8. The system SHALL conform to function 8 A IN.1.9 (Patient Privacy and Confidentiality) 9. The system SHALL conform to function 9 A IN.1.10 (Secure Data Routing – LTC) S.1.1 F O Registry Notification Statement: Enable the automated transfer of IN.2.4 1. -

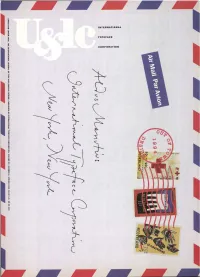

INTERNATIONAL TYPEFACE CORPORATION, to an Insightful 866 SECOND AVENUE, 18 Editorial Mix

INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION TYPEFACE UPPER AND LOWER CASE , THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF T YPE AND GRAPHI C DESIGN , PUBLI SHED BY I NTE RN ATIONAL TYPEFAC E CORPORATION . VO LUME 2 0 , NUMBER 4 , SPRING 1994 . $5 .00 U .S . $9 .90 AUD Adobe, Bitstream &AutologicTogether On One CD-ROM. C5tta 15000L Juniper, Wm Utopia, A d a, :Viabe Fort Collection. Birc , Btarkaok, On, Pcetita Nadel-ma, Poplar. Telma, Willow are tradmarks of Adobe System 1 *animated oh. • be oglitered nt certain Mrisdictions. Agfa, Boris and Cali Graphic ate registered te a Ten fonts non is a trademark of AGFA Elaision Miles in Womb* is a ma alkali of Alpha lanida is a registered trademark of Bigelow and Holmes. Charm. Ea ha Fowl Is. sent With the purchase of the Autologic APS- Stempel Schnei Ilk and Weiss are registimi trademarks afF mdi riot 11 atea hmthille TypeScriber CD from FontHaus, you can - Berthold Easkertille Rook, Berthold Bodoni. Berthold Coy, Bertha', d i i Book, Chottiana. Colas Larger. Fermata, Berthold Garauannt, Berthold Imago a nd Noire! end tradematts of Bern select 10 FREE FONTS from the over 130 outs Berthold Bodoni Old Face. AG Book Rounded, Imaleaa rd, forma* a. Comas. AG Old Face, Poppl Autologic typefaces available. Below is Post liedimiti, AG Sitoploal, Berthold Sr tapt sad Berthold IS albami Book art tr just a sampling of this range. Itt, .11, Armed is a trademark of Haas. ITC American T}pewmer ITi A, 31n. Garde at. Bantam, ITC Reogutat. Bmigmat Buick Cad Malt, HY Bis.5155a5, ITC Caslot '2114, (11 imam. -

2.1 Typography

Working With Type FUN ROB MELTON BENSON POLYTECHNIC HIGH SCHOOL WITH PORTLAND, OREGON TYPE Points and picas If you are trying to measure something very short or very thin, then inches are not precise enough. Originally English printers devised picas to precisely measure the width of type and points to precise- ly measure the height of type. Now those terms are used interchangeably. There are 12 points in one pica, 6 picas in one inch — or 72 points in one inch. This is a 1-point line (or rule). 72 of these would be one inch thick. This is a 12-point rule. It is 1 pica thick. Six of these would be one inch thick. POINTS PICAS INCHES Thickness of rules I Lengths of rules Lengths of stories I Sizes of type (headlines, text, IWidths of text, photos, cutlines, IDepths of photos and ads cutlines, etc.) gutters, etc. (though some publications use IAll measurements smaller than picas for photo depths) a pica. Type sizes Type is measured in points. Body type is 7–12 point type, while display type starts at 14 point and goes to 127 point type. Traditionally, standard point sizes are 14, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 54, 60 and 72. Using a personal computer, you can create headlines in one-point increments beginning at 4 point and going up to 650 point. Most page designers still begin with these standard sizes. The biggest headline you are likely to see is a 72 pt. head and it is generally reserved for big stories on broadsheet newspapers. -

A Tool for Facilitating OCR Postediting in Historical Documents

Proceedings of 1st Workshop on Language Technologies for Historical and Ancient Languages, pages 47–51 Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC 2020), Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC A Tool for Facilitating OCR Postediting in Historical Documents Alberto Poncelas, Mohammad Aboomar, Jan Buts, James Hadley, Andy Way ADAPT Centre, School of Computing, Dublin City University, Ireland Trinity Centre for Literary and Cultural Translation, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland falberto.poncelas, jan.buts [email protected] fABOOMARM, [email protected] Abstract Optical character recognition (OCR) for historical documents is a complex procedure subject to a unique set of material issues, including inconsistencies in typefaces and low quality scanning. Consequently, even the most sophisticated OCR engines produce errors. This paper reports on a tool built for postediting the output of Tesseract, more specifically for correcting common errors in digitized historical documents. The proposed tool suggests alternatives for word forms not found in a specified vocabulary. The assumed error is replaced by a presumably correct alternative in the post-edition based on the scores of a Language Model (LM). The tool is tested on a chapter of the book An Essay Towards Regulating the Trade and Employing the Poor of this Kingdom (Cary, 1719). As demonstrated below, the tool is successful in correcting a number of common errors. If sometimes unreliable, it is also transparent and subject to human intervention. Keywords: OCR Correction, Historical Text, NLP Tools 1. Introduction The approaches involving image-processing perform mod- Historical documents are conventionally preserved in phys- ifications on the scanned book that make the OCR perform ical libraries, and increasingly made available through dig- better. -

Corel® Wordperfect® Office 2020 Handbook

Handbook Part One: Introduction 3 getting started Part Two: WordPerfect 15 creating professional-looking documents Part Three: Quattro Pro 133 managing data with spreadsheets Part Four: Presentations 183 making visual impact with slide shows Part Five: Utilities 241 using WordPerfect Lightning, Address Book, and more Part Six: Writing Tools 259 checking your spelling, grammar, and vocabulary Part Seven: Macros 273 streamlining and automating tasks Part Eight: Web Resources 283 finding even more information on the Internet Handbook highlights What’s included? . 3 What’s new in WordPerfect Office 2020 . 11 Installation . 11 Help resources. 5 Documentation conventions . 6 WordPerfect basics . 17 Quattro Pro basics. 135 Presentations basics . 185 WordPerfect Lightning . 243 Index. 285 Part One: Introduction Welcome to the Corel® WordPerfect® Office 2020 Handbook! More than just a reference manual, this handbook is filled with valuable tips and insights on a wide variety of tasks and projects. The following chapters in this introductory section are key to getting started with the software: • What’s new in WordPerfect Office 2020 on page 11 • Installation on page 11 • Using the Help files on page 6 If you’re ready to explore specific components of the software in greater detail, see the subsequent sections in this handbook. For an A-to-Z look at the topics covered in this manual, see the index on page 285. What’s included? WordPerfect Office includes the following programs: • Corel® WordPerfect® — for creating professional-looking documents. See Part Two: WordPerfect on page 15. • Corel® Quattro Pro® — for managing, analyzing, reporting, and sharing data. See Part Three: Quattro Pro on page 133. -

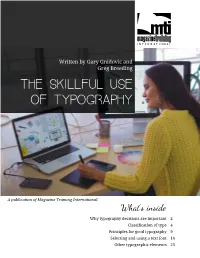

The Skillful Use of Typography

Written by Gary Gnidovic and Greg Breeding The Skillful Use Of Typography A publication of Magazine Training International. What’s inside Why typography decisions are important 2 Classification of type 4 Principles for good typography 9 Selecting and using a text font 14 Other typographic elements 23 Share your thoughts with #MTIebook Chapter 1 Why typography decisions are important Aaron Burns, an influential designer and founder of the International Typeface Corporation (ITC), once said, “In typography, function is of major importance, form is secondary, and fashion [trend] is almost meaningless.” Although this may sound like an extreme view, it holds a great deal of truth. If we choose to work well with our type, concentrating on its purpose, appropriateness, and legibility, our magazines will begin to take on an air of authenticity and integrity. Rather than blindly following stylistic trends in typography, intelligent, careful attention to detail will pave the way for a more expressive, creative approach. THE SKILLFUL USE OF TYPOGRAPHY 2 Share your thoughts with #MTIebook The skillful use of type in magazine design is an area where, even with limited resources, we can do a great deal to enhance the look and feel of our publications. The creative application of a couple of well-chosen font families is often preferable to a CD containing “600 Cool Fonts for Every Purpose.” This e-book will offer some principles that will help establish a firm foundation on which to build the visual approach to your magazine. THE SKILLFUL USE OF TYPOGRAPHY Chapter 1 3 Share your thoughts with #MTIebook Chapter 2 Classifications of type There are two major classifications of type: serif and sans-serif.