Chapter 31 the Weirdos (Part 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

Tense, Time, Aspect and the Ancient Greek Verb by Jerome Moran

Tense, Time, Aspect and the Ancient Greek Verb by Jerome Moran early every – no, every – Greek The questions in the first sentence 3. In Greek the tense of a verb may Ngrammar and course book, even (‘deliberative’ questions, therefore in denote something different from or the most comprehensive (in English, the subjunctive) refer to present (or additional to the time at which the at any rate), gives a very skimpy, perhaps future) time. But one of act, event, occurrence, process, state perfunctory and unhelpful account — the verbs (εἴπωμεν) is in a past denoted by the verb is located. In insofar as it gives any account at all – of tense (aorist). The second sentence particular, it may denote something what ‘aspect’ is and how exactly it is refers to past time, but one of the called ‘aspect’. related to verb tense and time (which verbs (βούλοιτο) is in the present tend to be conflated). Most of the tense. 4. Whether the tense of a Greek verb books and articles on the subject of denotes time or/and aspect depends the aspect of the Greek verb are What is going on? The answer is in the first place on the mood of the accessible only to the professional something called ‘aspect’, and its verb (‘the form which a verb philologist, and can’t therefore be connection with tense and time. Just assumes in order to reflect the easily applied by non-specialists to the note for now a difference in the manner (modus) in which the speaker understanding of the actual usage of kind of things denoted by the verbs conceives the action’ (Woodcock)). -

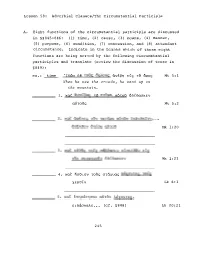

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

The Indo-European K-Aorist

Frederik Kortlandt, Leiden University, www.kortlandt.nl The Indo-European k-aorist Ten years ago I wrote (2007: 155f.): “It has been impossible to establish an original meaning for the alleged velar suffix in the root aorists fēcī and iēcī (cf. Untermann 1993). I therefore think that we have to look for a phonetic explanation. Since the -k- is limited to the singular in the Greek active aorist indicative, I am h inclined to regard fēc- as the phonetic reflex of monosyllabic *dhēk < *d eH1t, where *-k- may have been either an intrusive consonant after the laryngeal before the final *-t, like -p- in Latin emptus ‘bought’ or *-s- in Hittite ezta ‘he ate’ < *edto, or a remnant of the Indo-Uralic velar consonant from which the laryngeal developed, as in Finnish teke- ‘make’ (cf. Kortlandt 2002: 220). The present stems of faciō and iaciō support the former possibility. This would also account for Tocharian A tāk, B tāka ‘became’, h h which reflect *steH2t. In a similar vein I reconstruct *hēp < *g eH1b t and *sēp < *seH1pt for Oscan hipid, hipust ‘will hold’, sipus ‘knowing’. While Oscan hafiest ‘will hold’ is in accordance with the Latin, Celtic and Germanic evidence, Umbrian hab- suggests that h h h *g eH1b - yielded *g eb- with preglottalized *-b- at an early stage and that this root- final consonant was generalized in Italic. It appears that Latin capiō ‘take’ < *kH2p- adopted the -ē- of cēpī from its synonym apiō, ēpī, and that scabō, scābī ‘scratch’ reflects original *skebh- (cf. Schrijver 1991: 431).” As Untermann observes (1993: 463), the Latin stems fac- and iac- behave as roots of primary verbs, and the same holds for Sabellic and Venetic. -

Greek Tenses in John's Apocalypse

CHAPTER 13 Greek Tenses in John’s Apocalypse: Issues in Verbal Aspect, Discourse Analysis, and Diachronic Change Buist M. Fanning This essay will concentrate on discourse functions for the Greek tenses in the Apocalypse of John. I will pursue this through a dialogue with and critique of David Mathewson’s views as presented in his 2010 monograph published by Brill and an earlier article in Novum Testamentum (2008) on this topic.1 Mathewson’s work is a reflection of a larger school of thought on nt Greek ver- bal usage that has been influenced greatly by Stanley Porter, and so this gives me an opportunity to interact with the views of a larger group of recent writers based on work that I have done on verbal aspect in nt Greek.2 The issue that triggers this discussion is what some have called the confu- sion of tenses or erratic shifting of tenses in John’s Apocalypse, just one area of the larger topic of John’s solecisms or unusual Greek grammatical expressions.3 What Mathewson argues for (following Porter) and what I will dispute in this paper is twofold: (1) that aspect alone is the focus of the ancient Greek tense forms; they do not in themselves express any temporal meaning; in regard to the Apocalypse if we take time out of the equation, we eliminate all of the supposed problems with shifting tense forms; (2) the main secondary effect of aspect is a certain function to reflect discourse prominence, that is, back- ground, foreground, and frontground events or features in a text. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

Tense in Time: the Greek Perfect 1

Gerš/Stechow Draft 8. January 2002: EVA-CARIN GER… AND ARNIM VON STECHOW TENSE IN TIME: THE GREEK PERFECT 1. Survey .................................................................................................................................1 2. On the Tense/Aspect/Aktionsart-architecture .......................................................................4 3. Chronology of Tense/Aspect Systems................................................................................10 3.1. Archaic Greek (700-500 BC) .....................................................................................11 3.2. Classical (500 Ð 300 BC)............................................................................................18 3.3. Postclassical and Greek-Roman (300 BC Ð 450 AD)..................................................29 3.4. Transitional and Byzantine/Mediaeval Period (300 Ð 1450 AD) .................................31 3.5. Modern Greek (From 1450 AD).................................................................................33 4. Conclusion.........................................................................................................................35 * 1. SURVEY The paper will deal with the diachronic development of the meaning and form of the Greek Perfect. The reason for focusing on this language is twofold: first, it has often been neglected in the modern linguistic literature about tense; secondly, in Greek, it is possible to observe (even without taking into account the meaning and form of the Perfect in Modern -

A Discourse Analysis of the Periphrastic Imperfect In

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE PERIPHRASTIC IMPERFECT IN THE GREEK NEW TESTAMENT WRITINGS OF LUKE by CARL E. JOHNSON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2010 Copyright © by Carl Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to express my sincere appreciation to each member of my committee whose helpful criticism has made this project possible. I am indebted to Don Burquest for his incredible attention to detail and his invaluable encouragement at certain critical junctures along the way; to my chair Jerold A. Edmondson who challenged me to maintain a linguistic focus and helped me frame this work within the broader linguistic perspective; and to Dr. Chiasson who has helped me write a work that I hope will be accessible to both the linguist and the New Testament Greek scholar. I am also indebted to Robert Longacre who, as an initial member of my committee, provided helpful insight and needed encouragement during the early stages of this work, to Alicia Massingill for graciously proofing numerous editions of this work in a concise and timely manner, and to other members of the Arlington Baptist College family who have provided assistance and encouragement along the way. Finally, I am grateful to my wife, Diana, whose constant love and understanding have made an otherwise impossible task possible. All errors are of course my own, but there would have been far more without the help of many. -

An Introduction to Dena'ina Grammar

AN INTRODUCTION TO DENA’INA GRAMMAR: THE KENAI (OUTER INLET) DIALECT by Alan Boraas, Ph.D. Professor of Anthropology Kenai Peninsula College Based on reference material by: Peter Kalifornsky James Kari, Ph.D. and Joan Tenenbaum, Ph.D. June 30, 2009 revisions May 22, 2010 Page ii Dedication This grammar guide is dedicated to the 20th century children who had their mouth’s washed out with soap or were beaten in the Kenai Territorial School for speaking Dena’ina. And to Peter Kalifornsky, one of those children, who gave his time, knowledge, and friendship so others might learn. Acknowledgement The information in this introductory grammar is based on the sources cited in the “References” section but particularly on James Kari’s draft of Dena’ina Verb Dictionary and Joan Tenenbaum’s 1978 Morphology and Semantics of the Tanaina Verb. Many of the examples are taken directly from these documents but modified to fit the Kenai or Outer Inlet dialect. All of the stem set and verb theme information is from James Kari’s electronic Dena’ina verb dictionary draft. Students should consult the originals for more in-depth descriptions or to resolve difficult constructions. In addition much of the material in this document was initially developed in various language learning documents developed by me, many in collaboration with Peter Kalifornsky or Donita Peter for classes taught at Kenai Peninsula College or the Kenaitze Indian Tribe between 1988 and 2006, and this document represents a recent installment of a progressively more complete grammar. Anyone interested in Dena’ina language and culture owes a huge debt of gratitude to Dr. -

The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect Version 1.0 July 2007 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: The origin of the pluperfect is the biggest remaining hole in our understanding of the Ancient Greek verbal system. This paper provides a novel unitary account of all four morphological types— alphathematic, athematic, thematic, and the anomalous Homeric form 3sg. ᾔδη (ēídē) ‘knew’—beginning with a “Jasanoff-type” reconstruction in Proto-Indo-European, an “imperfect of the perfect.” © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 The following paper has had a long history (see the first footnote). This version, which was composed as such in the first half of 2006, will be appearing in more or less the present form in volume 46 of the Viennese journal Die Sprache. It is dedicated with affection and respect to the great Indo-Europeanist Jay Jasanoff, who turned 65 in June 2007. *** for Jay Jasanoff on his 65th birthday The Oxford English Dictionary defines the rather sad word has-been as “One that has been but is no longer: a person or thing whose career or efficiency belongs to the past, or whose best days are over.” In view of my subject, I may perhaps be allowed to speculate on the meaning of the putative noun *had-been (as in, He’s not just a has-been; he’s a had-been!), surely an even sadder concept, did it but exist. When I first became interested in the Indo- European verb, thanks to Jay Jasanoff’s brilliant teaching, mentoring, and scholarship, the study of pluperfects was not only not a “had-been,” it was almost a blank slate. -

Errant Aorist Interpreters

Grace Theological Journal 2.2 (Fall 1981) 205-26. [Copyright © 1981 Grace Theological Seminary; cited with permission; digitally prepared for use at Gordon College] ERRANT AORIST INTERPRETERS CHARLES R. SMITH The thesis of this essay is that exegesis and theology have been plagued by the tendency of Greek scholars and students to make their field of knowledge more esoteric, recondite, and occult than is actually the case. There is an innate human inclination to attempt to impress people with the hidden secrets which only the truly initiated can rightly understand or explain. Nowhere is this more evident than in the plethora of arcane labels assigned to the aorist tense in its supposed classifications and significations. Important theological dis- tinctions are often based on the tense and presented with all the authority that voice or pen can muster. It is here proposed that the aorist tense (like many other grammatical features) should be "de- mythologized" and simply recognized for what it is--the standard verbal aspect employed for naming or labeling an act or event. As such, apart from its indications of time relationships, it is exegetically insignificant: (1) It does not necessarily refer to past time; (2) It neither identifies nor views action as punctiliar; (3) It does not indicate once- for-all action; (4) It does not designate the kind of action; (5) It is not the opposite of a present, imperfect, or perfect; (6) It does not occur in classes or kinds; and, (7) It may describe any action or event. * * * THE ABUSED AORIST In 1972 Frank Stagg performed yeoman service in publishing an article titled "The Abused Aorist."1 A number of the illustrations referred to in the following discussion are taken from his article.