Status of Sea Cucumber Populations at Ngardmau State Republic of Palau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

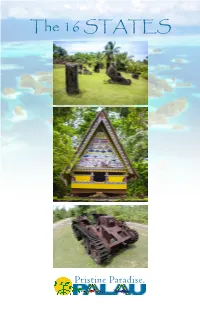

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Holothuriidae 1165

click for previous page Order Aspidochirotida - Holothuriidae 1165 Order Aspidochirotida - Holothuriidae HOLOTHURIIDAE iagnostic characters: Body dome-shaped in cross-section, with trivium (or sole) usually flattened Dand dorsal bivium convex and covered with papillae. Gonads forming a single tuft appended to the left dorsal mesentery. Tentacular ampullae present, long, and slender. Cuvierian organs present or absent. Dominant spicules in form of tables, buttons (simple or modified), and rods (excluding C-and S-shaped rods). Key to the genera and subgenera of Holothuriidae occurring in the area (after Clark and Rowe, 1971) 1a. Body wall very thick; podia and papillae short, more or less regularly arranged on bivium and trivium; spicules in form of rods, ovules, rosettes, but never as tables or buttons ......→ 2 1b. Body wall thin to thick; podia irregularly arranged on the bivium and scattered papillae on the trivium; spicules in various forms, with tables and/or buttons present ...(Holothuria) → 4 2a. Tentacles 20 to 30; podia ventral, irregularly arranged on the interradii or more regularly on the radii; 5 calcified anal teeth around anus; spicules in form of spinose rods and rosettes ...........................................Actinopyga 2b. Tentacles 20 to 25; podia ventral, usually irregularly arranged, rarely on the radii; no calcified anal teeth around anus, occasionally 5 groups of papillae; spicules in form of spinose and/or branched rods and rosettes ............................→ 3 3a. Podia on bivium arranged in 3 rows; spicules comprise rocket-shaped forms ....Pearsonothuria 3b. Podia on bivium not arranged in 3 rows; spicules not comprising rocket-shaped forms . Bohadschia 4a. Spicules in form of well-developed tables, rods and perforated plates, never as buttons .....→ 5 4b. -

2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU APPELLATE DIVISION NGEREMLENGUI STATE GOVERNMENT and NGEREMLENGUI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellants/Cross-Appellees, v. NGARDMAU STATE GOVERNMENT and NGARDMAU STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellees/Cross-Appellants. Cite as: 2016 Palau 24 Civil Appeal No. 15-014 Appeal from Civil Action No. 13-020 Decided: November 16, 2016 Counsel for Ngeremlengui ............................................... Oldiais Ngiraikelau Counsel for Ngardmau ..................................................... Yukiwo P. Dengokl Matthew S. Kane BEFORE: KATHLEEN M. SALII, Associate Justice LOURDES F. MATERNE, Associate Justice C. QUAY POLLOI, Associate Justice Pro Tem Appeal from the Trial Division, the Honorable R. Ashby Pate, Associate Justice, presiding. OPINION PER CURIAM: [¶ 1] This appeal arises from a dispute between the neighboring States of Ngeremlengui and Ngardmau regarding their common boundary line. In 2013, the Ngeremlengui State Government and Ngeremlengui State Public Lands Authority (Ngeremlengui) filed a civil suit against the Ngardmau State Government and Ngardmau State Public Lands Authority (Ngardmau), seeking a judgment declaring the legal boundary line between the two states. After extensive evidentiary proceedings and a trial, the Trial Division issued a decision adjudging that common boundary line. [¶ 2] Each state has appealed a portion of that decision and judgment. Ngardmau argues that the Trial Division applied an incorrect legal standard to determine the boundary line. Ngardmau also argues that the Trial Division Ngeremlengui v. Ngardmau, 2016 Palau 24 clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning parts of the common land boundary. Ngeremlengui argues that the Trial Division clearly erred in making factual determinations concerning a part of the common maritime boundary. For the reasons below, the judgment of the Trial Division is AFFIRMED. -

Conservation Areas

Republic of Palau Conservation Areas Palauans have always understood the intricate balance between the health of Palau’s natural habitats and the long-term health of its people. For many centuries, Palauans have practiced conservation and sustainable use of its natural habitats. To date, Palau has 290km² (112 square miles) of natural habitat, both marine and terrestrial, that is under some sort of protection. This is significant considering that Palau has a land mass of approximately 363 square kilometers. The national government, state governments, traditional leaders, NGOs, and the communities as a whole have all played a instrumental role in the creation and management of Palau’s conservation areas. Area Authority Year Approx size Regulations Ngerukewid Islands Wildlife no fishing, hunting, or Preserve (Seventy Islands Republic of Palau 1999 12km2 distrubance of any kind governed according to the reserve board Ngeruangel Reserve Kayangel State 1996 35km2 management plan Ngarchelong & Ngarchelong/Kayangel Reef Kayangel Chiefs - no fishing in 8 channels Channels Traditional bul 1994 90km2 during April through July Ebiil Channel Conservation Area Ngarchelong State 2000 15km2 no entry or fishing only traditional Ngaraard Conservation Area subsistence and (mangrove) Ngaraard State 1994 1.8km2 educational uses allowed Ngardmau Conservation Area (reef flat, Taki Waterfall, no entry, fishing, or Mount Ngerchelchuus) Ngardmau State 1998 7km2 hunting for 5 years Ngemai Conservation Area Ngiwal State 1997 1km2 no entry or fishing Ngerumekaol -

Republic of Palau Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, 2007-2012

National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007 - 2012 R National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 To all Palauans, who make the Cancer Journey May their suffering return as skills and knowledge So that the people of Palau and all people can be Cancer Free! Special Thanks to The planning groups and their chairs whose energy, Interest and dedication in working together to develop the road map for cancer care in Palau. We also would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant # U55-CCU922043) National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 October 15, 2006 Dear Colleagues, This is the National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau. The National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau provides a road map for nation wide cancer prevention and control strategies from 2007 through to 2012. This plan is possible through support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the Ministry of Health (Palau) and OMUB (Community Advisory Group, Palau). This plan is a product of collaborative work between the Ministry of Health and the Palauan community in their common effort to create a strategic plan that can guide future activities in preventing and controlling cancers in Palau. The plan was designed to address prevention, early detection, treatment, palliative care strategies and survivorship support activities. The collaboration between the health sector and community ensures a strong commitment to its implementation and evaluation. The Republic of Palau trusts that you will find this publication to be a relevant and useful reference for information or for people seeking assistance in our common effort to reduce the burden of cancer in Palau. -

Evaluation Report

EVALUATION REPORT Watamu Marine Protected Area Location: Kenyan Coast, Western Indian Ocean Blue Park Status: Nominated (2020), Evaluated (2021) MPAtlas.org ID: 68812840 Manager(s): Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) MAPS 2 1. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA 1.1 Biodiversity Value 4 1.2 Implementation 8 2. AWARD STATUS CRITERIA 2.1 Regulations 11 2.2 Design, Management, and Compliance 12 3. SYSTEM PRIORITIES 3.1 Ecosystem Representation 17 3.2 Ecological Spatial Connectivity 18 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: Evidence of MPA Effects 20 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: Additional species of 20 conservation concern MAPS Figure 1: Watamu Marine Protected Area includes Watamu Marine National Park (dark blue, indicating that it is fully protected), Watamu Marine National Reserve (light blue, indicating that it is highly protected), and half of Malindi-Watamu Marine National Reserve (light blue lined; it is also highly protected). Watamu Marine National Park is a no-take marine refuge which provides coral reefs and a variety of marine species with total protection from extractive exploitation. The adjacent Watamu Marine National Reserve protects the estuary known as Mida Creek and allows limited fishing. The Malindi-Watamu Marine National Reserve, located on the coastal side of Watamu Marine National Park, also allows limited fishing. See Section 2.1 for more information about the regulations of each zone. (Source: Kenya Wildlife Service, 2015) - 2 - Figure 2: Watamu National Marine Park (pink) sees high visitor use. The Watamu Marine Reserve (yellow) is a Medium Use Zone. The portion of the Malindi-Watamu Reserve within Watamu MPA (olive green) is a Low Use Zone, with respect to recreational activities. -

School Calendar 2021-2022 6.27.2020

School Calendar School Year 2021-2022 August 02, 2021 to May 13, 2022 MOE Vision & Mission Statements, Important Dates & Holidays STATE HOLIDAYS MINISTRY OF EDUCATION August 15 Peleliu State Liberation Day August 30 Aimeliik: Alfonso Rebechong Oiterong Day VISION STATEMENT: Cherrengelel a osenged el kirel a skuul. September 11 Peleliu State Constitution Day September 13 Kayangel State Constitution Day September 13 Ngardmau Memorial Day A rengalek er a skuul a mo ungil chad er a Belau me a beluulechad. September 28 Ngchesar State Memorial Day Our students will be successful in the Palauan society and the world. October 01 Ngardmau Constitution Day October 08 Angaur State Liberation Day MISSION STATEMENT: Ngerchelel a skuul er a Belau. October 08 Ngarchelong State Constitution Day October 21 Koror State Constitution Day November 05 Ngarchelong State Memorial Day A skuul er a Belau, kaukledem ngii me a rengalek er a skuul, rechedam me November 02 Angaur State Memorial Day a rechedil me a buai, a mo kudmeklii a ungil el klechad er a rengalek er a November 04 Melekeok State Constitution Day skuul el okiu a ulterekokl el suobel me a ungil osisechakl el ngar er a ungil November 17 Angaur: President Lazarus Salii Memorial Day el olsechelel a omesuub. November 25 Melekeok State Memorial Day November 27 Peleliu State Memorial Day January 06 Ngeremlengui State Constitution Day The Republic of Palau Ministry of Education, in partnership with students, January 12 Ngaraard State Constitution Day parents, and the community, is to ensure student success through effective January 23 Sonsorol State Constitution Day curriculum and instruction in a conducive learning environment. -

2014-2019 Palau National Review of Implementation of the Beijing Declaration -25Th Anniversary of the 4Th World Conference on Women

2014-2019 Palau National Review of Implementation of the Beijing Declaration -25th Anniversary of the 4th World Conference on Women Republic of Palau National Review for the Implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) and the outcomes of the twenty-third special session of the General Assembly (2000) in the context of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action 2020 April 2019 Submitted by Minister Baklai Temengil-Chilton Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs REPUBLIC OF PALAU Tel: (680) 767 1126 Fax: (680) 767 -3354 Compiled by Ann Hillmann Kitalong, PhD The Environment, Inc. 1 2014-2019 Palau National Review of Implementation of the Beijing Declaration -25th Anniversary of the 4th World Conference on Women Acknowledgements Many people contributed to the oversight, research, information, and writing of this review. We acknowledge Bilung Gloria G. Salii and Ebilreklai Gracia Yalap, the two highest ranking traditional women leaders responsible for the Mechesil Belau Annual Conference, that celebrated its 25th Anniversary in 2018. We especially thank Bilung Gloria G. Salii for giving the opening remarks for the validation workshop. We acknowledge the government of the Republic of Palau for undergoing the review, and for the open and constructive participation of so many participants. We wish to acknowledge the members of civil society and donor and development partners who participated in interviews and focus group discussion for their valuable insights. The primary government focal points were the Ministry of Community and Cultural Affairs (MCCA), Minister Baklai Temengil-Chilon; Director of Aging and Gender, Ms. -

Mme SLIMANE TAMACHA Farah

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UNIVERSITE ABDELHAMID IBN BADIS DE MOSTAGANEM FACULTE DES SCIENCES DE LA NATURE ET DE LA VIE DEPARTEMENT DES SCIENCES DE LA MER ET DE L’AQUACULTURE Laboratoire de Protection, Valorisation des Ressources Marine Littoral et Systématique Moléculaire THESE En vue de l’obtention du diplôme de Doctorat en sciences Filière : hydrobiologie marine et continentale Spécialité : biologie écologie marine. Présenté par : Mme SLIMANE TAMACHA Farah Thème Les Holothuries Aspidochirotes de la côte Ouest Algérienne : biologie, écologie et exploitation Soutenue le 08/ 12/ 2019 Devant le jury composé de : M. TAIBI N. Professeur Univ. Abdelhamid Ibn Badis Président Mostaganem M. ROUANE-HACENE O. MCA Univ. d’Oran1 Ahmed Ben Bella Examinateur Mme TALEB BENDIAB A-A. MCA Univ. d’Oran1 Ahmed Ben Bella Examinatrice Mme SOUALILI D.L. Professeur Univ. Abdelhamid Ibn Badis Examinatrice Mostaganem BENDIMERAD M. E-A MCA Univ. Abou Bakr Belkaid Tlemcen Examinateur M. MEZALI K. Professeur Univ. Abdelhamid Ibn Badis Directeur de thèse Mostaganem Année universitaire 2019-2020 Avant propos La présente thèse de doctorat s’appuie sur l’étude de la biologie de la reproduction, la croissance et la dynamique des populations de certaines holothuries de la région de Ain Franine. Les révisions et actualisations de la systématique des holothuries ou « concombre de mer » a connu de multitude mis à jours depuis le commencement de cette thèse en 2013, parmis ces révisions on note l’ordre des Aspidochirotida, qui depuis 2018 a été remplacé par l’ordre Holothuriida. WoRMS (Registre mondial des espèces marines) comme base de données taxonomiques modernes accepte cette modification, l’utilisation de cette nouvelle classification était utilisé tout le long de la rédaction de cette thèse, et vue qu’on ne peut changer le titre initial de la thèse (selon les recommandations de la VRPG de l’université de Mostaganem) on a gardé l’ancienne classification. -

Proposed National Landfill Project

Environmental Impact Statement for The Proposed National Landfill Imul Hamlet, Aimeliik State Alternate Site A at Ongerarekieu, Imul Hamlet Aimeliik in 2009 Proposed National Landfill Alternative Site B at Ngeruchael, Imul Hamlet Aimeliik in 2017 March 2017 Prepared for: Prepared By: Capital Improvement Project The Environment, Inc. Box 1696 Koror, Palau 96940 Koror, Palau 96940 The Environment, Inc. Proposed National Landfill 2/8/18 Draft EIS Alternative Site A Ongerarekieu and Alternate Site B Ngeruchael, Imul Hamlet Aimeliik State 1. Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 3. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Identification of the Applicant .................................................................................. 6 3.2 Identification of the Environmental Assessment Company that prepared the EA. .. 6 3.3 EA Process Documentation ...................................................................................... 8 3.4 Summary List of assessment methodology used for the land-based and water-based assessment of the project. ............................................................................................... 8 4. Detailed Project Description .................................................................................... -

SEA CUCUMBER and SEA Urcffln RESOURCES and BECHE-DE-MER INDUSTRY

18 SEA CUCUMBER AND SEA URCfflN RESOURCES AND BECHE-DE-MER INDUSTRY D. B. JAMES^ INTRODUCTION It prefers areas where calcareous alga Halimeda sp. on which it feeds is present. In some areas, especially in The Andaman and Nicobar Islands offer one of the Sesostris Bay, 10-15 Specimens are found in 25 sq.m most suitable habitats for sea cucumbers and sea urchins area. On the reef flat the size range is 200-300 mm and due to the presence of sheltered bays and lagoons. on the outer edge of the reef the specimens reach 500 The sea cucumbers prefer muddy or sandy flats and mm in length. This species was processed for the the sea urchins rocky coasts and algal beds. There first time in Andamans in 1976. It is to be noted that have been very few reports on these echinoderms of the H. atra has a toxin in the body wall in the living condi islands in the earlier years (Theel, 1882 ; Koehler and tion. Probably boiling and processing renders the Vaney, 1908 ; Koehler, 1927). More recently James product harmless. (1969) recorded several species of sea cucumbers and sea urchins from the islands. A specific account of Holothuria scabra (PI. I, A) is almost exclusively used the beche-de-mer resources of India was given by James in Andamans and on the mainland (Gulf of Mannar (1973). A cottage level export-oriented beche-de-mer and Palk Bay) due to its abundance, large size and" thick industry has been established in the Andamans since body wall. -

Palau: Facility for Economic and Infrastructure Management

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 40595 November 2007 Republic of Palau: Facility for Economic and Infrastructure Management Prepared by: Don Townsend, Infrastructure Specialist PINZ Wellington, New Zealand For Government of Palau and Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. November 2007 Project Number: TA 4929-PAL Facility for Economic & Infrastructure Management Project Infrastructure Specialist Assessment Report November 2007 Final Prepared for: Prepared by: Government of Palau & Don Townsend, Infrastructure Specialist Asian Development Bank PINZ Facility for Economic and Infrastructure Management Project CONTENTS Acronyms......................................................................................................................................iii Executive Summary...................................................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction............................................................................................................................ 7 II. Background ........................................................................................................................... 8 III. Approach ..............................................................................................................................