Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

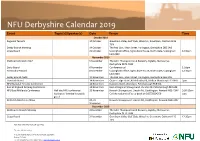

NFU Derbyshire Calendar 2019

NFU Derbyshire Calendar 2019 Event Topic(s)/Speaker(s) Date Venue Time October2019 Regional Tenants 14 October Greetham Valley Golf Club, Wood Ln, Greetham, Oakham LE15 7SN Derby Branch Meeting 14 October The Red Lion, Main Street, Hollington, Derbyshire DE6 3AG Crops Board 22 October Uppingham Office, Agriculture House, North Gate, Uppingham 12:30pm LE15 9NX November 2019 Melbourne Branch AGM 5 November The John Thompson Inn & Brewery, Ingleby, Melbourne, Derbyshire DE73 7HW Dairy Board 6 November Conference call 1:30pm Horticulture Board 8 November Uppingham Office, Agriculture House, North Gate, Uppingham 12:30pm LE15 9NX Derby Branch AGM 11 November The Red Lion, Main Street, Hollington, Derbyshire DE6 3AG Livestock Board 14 November Quorn Lodge Hotel, 46 Asfordby Rd, Melton Mowbray LE13 0HR 2pm NFU National Tenants Conference 14 November Haycock Hotel, Wansford, Peterborough PE8 6JA East of England Farming Conference 14 November East of England Showground, Oundle Rd, Peterborough PE2 6XE NFU East Midlands Conference Half day NFU conference 20 November Newark Showground, Lincoln Rd, Coddington, Newark NG24 2NY 9:30-10am looking at ‘farming for public Call the regional office to book on 01572 824250 start good’ Midlands Machinery Show 20, 21 Newark Showground, Lincoln Rd, Coddington, Newark NG24 2NY November December 2019 Melbourne Branch Meeting 3 December The John Thompson Inn & Brewery, Ingleby, Melbourne, Derbyshire DE73 7HW Crops Board 3 December Greetham Valley Golf Club, Wood Ln, Greetham, Oakham LE15 12:30pm 7SN NEW ADDITIONS -

Highfield Park, Fenny Bentley, Derbyshire

HIGHFIELD PARK, FENNY BENTLEY, DERBYSHIRE Archaeological Scoping Study Oxford Archaeology North November 2008 Rural Solutions Issue No: 2008-9\887 OA North Job No: L10082 NGR: SK 1710 5095 Highfield Park, Fenny Bentley, Derbyshire: Archaeological Scoping Study 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Circumstances of Project................................................................................. 5 1.2 Location, Topography and Geology ................................................................ 5 2. METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Design................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Legislative Framework.................................................................................... 6 2.3 Scoping Methodology..................................................................................... 6 3. HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND............................................ 8 3.1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Background.................................................................................................... -

Land at Blacksmith's Arms

Land off North Road, Glossop Education Impact Assessment Report v1-4 (Initial Research Feedback) for Gladman Developments 12th June 2013 Report by Oliver Nicholson EPDS Consultants Conifers House Blounts Court Road Peppard Common Henley-on-Thames RG9 5HB 0118 978 0091 www.epds-consultants.co.uk 1. Introduction 1.1.1. EPDS Consultants has been asked to consider the proposed development for its likely impact on schools in the local area. 1.2. Report Purpose & Scope 1.2.1. The purpose of this report is to act as a principle point of reference for future discussions with the relevant local authority to assist in the negotiation of potential education-specific Section 106 agreements pertaining to this site. This initial report includes an analysis of the development with regards to its likely impact on local primary and secondary school places. 1.3. Intended Audience 1.3.1. The intended audience is the client, Gladman Developments, and may be shared with other interested parties, such as the local authority(ies) and schools in the area local to the proposed development. 1.4. Research Sources 1.4.1. The contents of this initial report are based on publicly available information, including relevant data from central government and the local authority. 1.5. Further Research & Analysis 1.5.1. Further research may be conducted after this initial report, if required by the client, to include a deeper analysis of the local position regarding education provision. This activity may include negotiation with the relevant local authority and the possible submission of Freedom of Information requests if required. -

Directory of Churches

Directory of Churches www.derby.anglican.org Please email any amendments to [email protected] December 2016 Contents Contact Details Diocese of Derby 1 Diocesan Support Office, Church House 2 Area Deans 4 Board of Education 5 Alphabetical List of Churches 6 List of Churches - Archdeaconry, Deanery, Benefice, Parish & Church Order 13 Church Details Chesterfield Archdeaconry Carsington Deanery ................................................................................................................... 22 Hardwick Deanery ..................................................................................................................... 28 North East Derbyshire Deanery .................................................................................................. 32 Peak Deanery ............................................................................................................................. 37 Derby Archdeaconry City Deanery ............................................................................................................................... 45 Duffield & Longford Deanery ...................................................................................................... 51 Mercia Deanery .......................................................................................................................... 56 South East Derbyshire Deanery ................................................................................................. 60 Chesterfield Archdeaconry Carsington Deanery .................................................................................................................. -

Village & Community Magazine

VILLAGE & COMMUNITY MAGAZINE November Edition - 2019 Keeping Connected the Villages of ALSTONEFIELD ~ BUTTERTON ~ ELKSTONES ..... ILAMSee Inside ~ WARSLOW for August’s Specials~ WETTON..... DEADLINE for the December Magazine is **6pm FRIDAY** 22nd November “WHAT’S ON” NOVEMBER 2019 1st 7.30pm Butterton Bingo Butterton Village Hall 1st 7.00pm Live Comedy Performance ‘The Frozen Roman’ Alstonefield Village Hall 5th A.M. Ilam X Country Running Group (& every Tuesday) From Ilam 5th Evening Ilam School Association Bonfire & BBQ 6th Friendship Club Christmas Shopping Trip Burton on Trent 7th 3.30pm Pilates (& every Thursday) Beechenhill Hay Barn, Ilam 11th 7.30pm Hartington Surgery Patient Participation Meeting Hartington Surgery. 12th A.M. Ilam X Country Running Group (& every Tuesday) From Ilam 12th 8.00pm Ilam Parish Council Meeting Ilam School 12th 7.30pm Butterton W.I. (& every 2nd Tuesday) Butterton Village Hall 13th 10.00am Free Nordic Walking Taster Session National Trust, Ilam 13th 7.00pm Alstonefield History Group (Illustrated Talk) Alstonefield Village Hall 14th 1.15pm Free Nordic Walking Taster Session Old Dog, Thorpe 14th 3.30pm Pilates (& every Thursday) Beechenhill Hay Barn, Ilam 14th 7.30pm Wetton Parish Council Meeting Wetton Village Hall 18th 7.30pm Butterton Reading Group (& every 3rd Monday) Various Locations 18th 7.30pm Warslow Parish Council Meeting Warslow Village Hall 19th 7.30pm Body Shop Event Sheen Village Hall 19th A.M. Ilam X Country Running Group (& every Tuesday) From Ilam 19th 7.30pm CPR & Defibrillator Training Alstonefield Village Hall 20th 7.30pm Warslow Bingo Warslow Village Hall 21st 3.30pm Pilates (& every Thursday) Beechenhill Hay Barn, Ilam 23rd 7.30pm Live Music ‘Tom McConville Band’ Alstonefield Village Hall 24th 12 – 4pm Warslow Annual Christmas Fayre Warslow Village 26th A.M. -

Burials 1813 -1991

Burials 1813 -1991 Burial Surname Christian Description, notes, etc Abode Age Minister Death Name 1813-01-09 Wright Thomas FB 67 John Bowness 1813-02-20 Awkwright Richard Son of Richard Awkwright Esq. and Ashbourne Inf Geo.Roe, Rector Martha his wife 1813-03-11 Bowler Elizabeth Daughter of Isaac and Hannah FB 7 Geo.Roe, Rector 1813-03-19 Awkwright Agnes Daughter of Richard Awkwright Esq. Ashbourne 4 Geo.Roe, Rector and Martha his wife 1813-05-03 Waterfall Sarah Daughter of William and Elizabeth FB 33 Geo.Roe, Rector 1814-05-20 Hodgkinson William Son of William and Hannah Sturston, 4 Geo.Roe, Rector Ashbourne 1814-09-11 Bowler William FB 59 Geo.Roe, Rector 1814-10-12 Bowler Elizabeth Wife of Joseph Woodeaves, 40 Geo.Roe, Rector Tissington 1814-10-13 Rangedale Thomas FB 68 Geo.Roe, Rector 1814-11-27 Wright Elizabeth Daughter of Richard and Hannah FB Inf Geo.Roe, Rector 1814-12-01 Bowler Hannah Wife of Jacob FB 26 Geo.Roe, Rector 1814-12-01 Bowler Maria Daughter of Jacob and Hannah FB Inf Geo.Roe, Rector 1815-01-08 Irons John FB 38 Geo.Roe, Rector 1815-03-01 Bowler Lydia Margaret Wife of Joseph FB 21 John Bowness 1815-04-26 Davis Sarah Illegitimate daughter of Mary FB 3m John Bowness 1815-04-30 Beresford Alice Widow of Richard Beresford Esq of Ashbourne 78 Geo.Roe, Rector Ashbourne (father of Richard, who died in Wales) 1815-06-17 Bowler Ann Daughter of Joseph Woodeaves, 19 John Bowness Tissington 1815-08-25 Beresford Fanny Widow of the late Francis Beresford Ashbourne 75 Geo.Roe, Rector Esq. -

Fenny Bentley Biographies

FENNY BENTLEY BIOGRAPHIES 1 Ambulford, Simon Rector of Fenny Bentley 1432 - 1443 Attlowe, Robert de Rector of Fenny Bentley 1362 - 1374 Baggaley, Charles Rector of Fenny Bentley 1925 - 1927 1908 Deacon of St. Philip's Dewsbury 1911 Moved to Barton on Humber 1915 Moved to Ratcliffe on Trent. Served as army chaplain in war 1919 - 1925 Newark 10 June 1925 Inducted as Rector of Fenny Bentley by Archdeacon Noakes. Ballidon, Roger de Rector of Fenny Bentley 1361 - 1362 Bamford, Nicholas Rector of Fenny Bentley 12 Sept 1561 - Feb 1564 Deprived of the living Feb 1564 Barnes, Jeremiah M.A. Born 1808 Died 24 Feb 1883 Sometime Vicar of Tissington (1879 according to Kelly 1936 although this may be the date of the window to his wife ); former Rural Dean of Leek In 1834 Jeremiah Barnes, assistant curate at St. Edward's, Leek and master of the grammar school, started a monthly lecture at the school. It was so well attended that he began a lecture and service in the church every Sunday evening later the same year. A subscription was started in 1835 to meet the cost, including a stipend of £30 a year for the lecturer; in addition a special sermon was preached annually to raise funds. Barnes also started cottage lectures. The Sunday evening lecture continued at least until 1888. Attendances at the services on Census Sunday 1851 were 350 in the morning and 200 in the afternoon, besides Sunday school children, and 550 in the Having been 'Rector designate' of Bentley, stood down in favour of Edward Hayton in 1877 Purchased Bank Top Farm in 1852 when the Irving and Jackson estate was broken up and converted the old farmhouse into Bentley Cottage (now The Bentley Brook Inn) as his 'occasional residence'. -

Listing Showing Events from 07/07/2016 to 17/07/2016 and Within 12 Miles of Ashbourne

Listing showing events from 07/07/2016 to 17/07/2016 and within 12 miles of Ashbourne Time to....... www.visitpeakdistrict.com Parwich Wakes Week at Parwich Parwich, Derbyshire, DE6 1QL 2nd Jul 2016 - 9th Jul 2016 Contact: Parwich.org Email: [email protected] Web: https://parwich.org/2016/06/30/parwich-wakes-summary-of-events/ A packed week of events in the pretty village with its old pond and green. Situated in the scenic hill country of the White Peak. Nestling with its' back' against Parwich Hill. Matlock Artists Society Exhibition at Carsington Water Visitor Centre Carsington Water Visitor Centre, Carsington Water, Carsington, Ashbourne, Derbyshire, DE6 1ST 2nd Jul 2016 - 10th Jul 2016 10:00-16:00 Contact: Carsington Visitor Centre Art Exhibition by various artists in the Henmore Room Summer Gardens at Hopton Hall Hopton Hall , Hopton, Wirksworth, Matlock, Derbyshire, DE4 4DF 5th Jul 2016 - 7th Jul 2016 10:30-16:00 12th Jul 2016 - 14th Jul 2016 10:30-16:00 Contact: Hopton Hall Tel: 01629 540923 Web: http://www.hoptonhall.co.uk £4.00 per person Summer garden spectacular with visual surprises at each corner. ‘Blithe Spirit’ by Noel Coward at Denstone Denstone, Uttoxeter, Staffordshire, ST14 5DR 7th Jul 2016 - 9th Jul 2016 19:30 Contact: Tickets Tel: 01538 722667 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.denstoneplayers.com Tickets £7.00 Fussy, cantankerous novelist Charles Condomine, re-married but haunted (literally) by the ghost of his late first wife, the clever and insistent Elvira who is called up by a visiting "happy medium", one Madame Arcati. -

Heritage Impact Assessment

The Ashes Farm, Fenny Bentley, Derbyshire Heritage Impact Assessment Project Reference: 21-020 Produced for Robert Winter August 2021 WWW.LOCUSCONSULTING.CO.UK Heritage Impact Assessment – The Ashes Farm, Fenny Bentley Locus Consulting Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Project Background ....................................................................................................... 6 1.2 The Site ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Proposed Works ............................................................................................................ 8 1.4 Scope of Study .............................................................................................................. 9 1.5 Planning Context ......................................................................................................... 10 1.6 Planning History .......................................................................................................... 11 SITE CONTEXT .............................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Historical Development ............................................................................................... 12 2.3 -

Ej..-Jtt O TCP31SSUED

RECEIVED AT P.FILE 1 CODE No. NPWED0193 012 DISTRICT _1 N~ 019: __ . 15 Jan 1993 GRID REF 1694 5098 OS MAP No. 1650 RECEIVED AT c/o AGENT APPLICANT PPJPB A J Startin Mr & Mrs Redfern 15 Jan 1993 62 Carter Street Highfields Caravan Park UTTOXETER Fenny Bentley PLOTTED Staffordshire 23 Dec 1992 ASHBOURNE SH Derbyshire ENTERED IN POSTCODE REGISTER POSTCODE Tel No. 0889568056 Tel No. ENTERED BY SVS CERTIFICA TE TYPE Full APPL A calor tank, bottle storage, garage, site PROPOSAL Retain games area, site shop, gas gas f.- store, recreation room and workshop PROPOSED LAND USE Highfields Caravan Park CARA IIOCATION 1--. - EXISTING PARISH Fenny Bentley C) LAND USE LAST ADVERT DATE 19 Feb 1993 ADVERT DATE 29 Jan 1993 PREVIOUS APP CONSTRAINTS PLANNING OFFICER JK DATE SENT DATE REPLY CONSULTATIONS \.' ' '... 18 Jan 1993 -': \,:1. Rivers Authority National I? ,- TCP3 DRAFT 18 Jan 1993 \ -,.' l Severn Trent Water \ 18 Jan 1993 .\.~ Council \)~ Fenny Bentley Parish .y . 18 Jan 1993 , , Derbyshire Dales District Council f-. - 18 Jan 1993 COMMITTEE Derbyshire County Council (Highways) eJ..-Jtt o TCP31SSUED .., (1 "2, (\.S --- ~ DEEMED REFUSAL DATE 12 Mar 1993 13 WEEKS DATE 21 Apr 1993 _..~ ~ - IN P Registry - THIS CARD SHOULD BE FILED IMMEDIA'lELY lD\<1-S FRONT OF THE YELLOW DECISION NOTICE WHICH IN 'IURN SHOULD BE IMMEDIA'lELY IN FRONT OF NP/v::m C,:;zb2. A SET OF APPROVED PLANS. ENFORCEMENT RECORD CARD Record site visits overleaf - this side to be used for addi tional notes as appropria te. \.,.; '-' NOTE The following amendments have been formally agreed since the issue of the decision notice. -

Vicar's Letter

GROUP MAGAZINE St. Edmund’s St. Mary’s Fenny Bentley Tissington JULY and AUGUST 2011 50p St. Michael & All Angel’s Alsop-en-le-Dale St. Peter’s St. Leonard’s Parwich Thorpe WHITE PEAK D G Woodwork FARM BUTCHERY CARPENTRY & JOINERY MEAT AT ITS PEAK SPECIALIST • The Old Slaughterhouse SMALL JOBS UNDERTAKEN Chapel Lane, Tissington Nr. Ashbourne, DE6 1RA David Goldstraw Tel: 01335 390300 01335 390370 or 07749 629710 THE COACH & HORSES Fenny Bentley, Nr. Ashbourne. A friendly 17th century coaching inn, open all day, every day. Good food, good beers and warming log fires. Telephone: 01335 350246 Your local distributer for ASHBOURNE AGRICULTURAL secretarial and printing services FARM & ROAD FUELS LUBRICANTS A traditional secretarial service DOMESTIC HEATING OIL PEAK OIL PRODUCTS combined with modern print PEAK OIL PRODUCTS (NORTHERN) LTD technology SHOTTLE STATION, COWERS LANE Tel: 01335 300445 • Fax: 300485 BELPER, DERBYSHIRE. DE56 2LG Ashbourne Business Centre, Dig Street, Ashbourne TEL: 01773 550417 www.ashbournesecretarialandprintingservices.com Email: [email protected] Fax: 01773 550481 STURSTON FOR SERVICE JOHN HAMBLETON BUILDING & ROOFING For ALL your Motoring • Requirements STONE MASONRY • 01335 342512 EXPERIENCED IN WORKING WITH www.sturstongarage.co.uk LOCAL MATERIALS Sturston Garage Limited Airfield Industrial Estate, Ashbourne TEL: 01335 350574 Dear friends The rain is washing against my study window heralding the arrival of a truly British summer! Not that I'm complaining, wilted plants are starting to look a little greener. With the arrival of summer come the thoughts of vacation. Time to relax, rest and perhaps catch up with family and friends. For many, life rushes past at an alarming rate. -

Notice of Poll Notice Is Hereby Given That

Derbyshire County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE DOVEDALE DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for will be held on Thursday 4 May 2017, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm in this Division. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The following people stand nominated for election to this Division SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS SASKIA TALLIS, DOROTHY M DOBBS, SARAH K AITON, ELISABETH R AITON, BEN J FURNESS, ALESIA 43 GREENWAY ASHBOURNE FURNESS, VICTORIA J WRIGHT, AITON MARTIN Liberal Democrats DERBYSHIRE DE6 1EF STEPHEN J MILLS, SUSAN BIBBY, JOSEPH BIBBY ANNE CROASDELL, MAGGIE M FORD, PETER R CORK, L A COOPER, PAUL FLINT, STUART CUNNINGHAM, WOODLAND COTTAGE WELL DAVID L WAIN, SALLYANN CARLIN, BARKER TOM Labour Party GREEN CALVER S32 3XX CHARLES MONKHOUSE, SUSAN WATMORE STEPHEN HALL, JOHN LESLIE BIRKETT, PAMELA WOODRUFF, FRANCIS WOODRUFF, SUSAN BULL, ROSE VIEW ROSTON The Conservative JOHN SMITH, GAVIN SCZESNIOK, SPENCER SIMON ASHBOURNE DERBYSHIRE DE6 Party Candidate JOHN M HARRISON, STEPHEN 2EH BRYAN, ANDY ROGERS NIGEL BRUNEL MASON, ANNE PATRICIA WELLINGTON, PAULINE ANN MASON, JOHN ANDREW LABURNUM COTTAGE WELL Independent WELLINGTON, ANDREW PHILIP SWINDELL COLIN STREET ELTON MATLOCK DE4 Candidate BROWN, ANNA NATALIE BROWN, 2BY ANTHONY MALLICHAN, JANET CHRISTINE MALLICHAN, SUSAN LIGHTFOOT, JOHN B LIGHTFOOT IAN BRIGHT, DAVID A SKINNER, JEAN YOUATT, CHRISTOPHER J HOWLEY, EVE HOWLEY, JOAN M 17 NEW ROAD YOULGRAVE The Green Party STEED, JANINE SHEARING, MARK R YOUATT JOHN ROBIN BAKEWELL Candidate SHEARING, GLENYS A MOORE, ANDREW J BAKER Dated: 5 April 2017 Sandra Lamb Deputy Returning Officer Printed and published by The Deputy Returning Officer, Derbyshire Dales District Council, Town Hall, Matlock DE4 3NN 4.