Emotional Literacy and Whole School Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

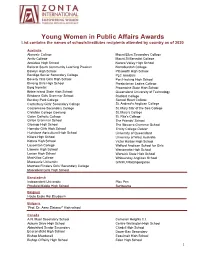

Young Women in Public Affairs Awards List Contains the Names of Schools/Institutes Recipients Attended by Country As of 2020

Young Women in Public Affairs Awards List contains the names of schools/institutes recipients attended by country as of 2020 Australia Alanvale College Mount Eliza Secondary College Amity College Mount St Benedict College Armidale High School Narara Valley High School Ballarat South Community Learning Precinct Narrabundah College Balwyn High School Pittsworth High School Bendigo Senior Secondary College PLC Armidale Beverly Hills Girls High School Port Hacking High School Birrong Girls High School Presbyterian Ladies College Borg Nonntal Proserpine State High School Bribie Island State High School Queensland University of Technology Brisbane Girls Grammar School Radford College Buckley Park College Sacred Heart College Canterbury Girls' Secondary College St. Andrew's Anglican College Castlemaine Secondary College St. Mary Star of the Sea College Christian College Geelong St. Mary’s College Galen Catholic College St. Rita's College Girton Grammar School The Friends' School Glossop High School The Illawarra Grammar School Hornsby Girls High School Trinity College Gawler Hurlstone Agricultural High School University of Queensland Killara High School University of West Australia Kotara High School Victor Harbor High School Laucenton College Walford Anglican School for Girls Lismore High School Wangaratta High School Loxton High School Warwick State High School MacKillop College Whitsunday Anglican School Macquarie University GWIKU Haizingergasse Matthew Flinders Girls' Secondary College Moorefield Girls High School Bangladesh Independent -

Report to Synod 2017

Report to Synod 2017 Contents Chairman's Report ....................................................1 Schools Members...................................................................2 Arndell Richard Johnson Corporation Anglican College .........................................10 Anglican School .........................................28 1. Background .........................................................3 Claremont Roseville College ........................................................12 College ........................................................30 2. Charter ................................................................3 3. Access .................................................................3 Danebank Rouse Hill School .........................................................14 Anglican College ........................................32 4. Management and Structure .................................3 4.1 Board ............................................................ 3 Macquarie Shellharbour Anglican Grammar School ..........................16 Anglican College ........................................34 4.2 Board Committees ....................................... 4 4.3 School Councils ........................................... 5 Mamre St Luke’s Anglican School ..........................................18 Grammar School ........................................36 4.4 Senior Officers of the Corporation ................ 5 4.5 Organisational Chart ................................... 5 Nowra Thomas Hassall Anglican College -

2019 Report to Synod 2019 Contents

Report to SYNOD2019 REPORT TO SYNOD 2019 CONTENTS Chairman’s Report Board Members 1. Background 2 Charter 3 Access 4 Management and Structure 4.1 Board 4.2 Board Committees 4.3 School Councils 4.4 Senior Officers of the Corporation 4.5 Organisational Chart 5. Summary Review of Activities 6. Financial Results (Summary) Our Schools Serving Christ REPORT TO SYNOD 2019 | 3 BOARD MEMBERS MR PHILIP BELL OAM MR ANDREW COX MR TONY WILLIS MRS JENNIFER EVERIST MR MARTYN MITCHELL REV KERRIE NEWMARCH BBuild CE(Hons) AAIQS ARI BA DipEd BTh JP DipTh JP BSc Chem Eng DipTheol (SMBC) CA BEd DipTeach AdvDipMin DipTh Chairman from July 2018 Deputy Chairman Retired July 2018 Rev Jennie Everist is Assistant Martyn currently chairs the Audit, Resigned Dec 2018 Philip was Managing Director of Resigned Dec 2018 Tony worked as a teacher and Minister at St Luke’s Anglican Risk and Finance Committee and Kerrie is Manager, Church a group of companies involved in Andrew chairs the Property and in parish ministry before joining Church Miranda, where she has has been an ASC Board Member Engagement & Training at printing, publishing, graphic design Asset Management Committee. Anglican Youthworks, coordinating been on staff for 18 years. As well as since 2014. With 30 years’ experience Anglican Deaconess Ministries. She and marketing. Now the Executive With a background in construction, Andrew the training of Youth and Children’s ministry being an ASC Board Member, she is also Chair as a PricewaterhouseCoopers chartered has contributed in many ways to Christian Chairman of Growth Coaching International, established a quantity surveying and construction staff. -

Chronology of Seventh-Day Adventist Education: 1872-1972

CII818L8tl or SIYIITI·Ill IIYIITIST IIUCITIGI CENTURY OF ADVENTIST EDUCATION 1872 - 1972 ·,; Compiled by Walton J. Brown, Ph.D. Department of Education, General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists ·t. 6840 Eastern Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20012 i/ .I Foreword In anticipation of the education centennial in 1972 and the publication of a Seventh-day Adventist chronology of education, the General Conference Department of Education started to make inquiries of the world field for historical facts and statistics regarding the various facets of the church program in education. The information started to come in about a year ago. Whlle some of the responses were quite detalled, there were others that were rather general and indefinite. There were gaps and omissions and in several instances conflicting statements on certain events. In view of the limited time and the apparent cessation of incoming materials from the field, a small committee was named with Doctor Walton J. Brown as chairman. It was this committee's responsibility to execute the project in spite of the lack of substantiation of certain information. We believe that this is the first project of its kind in the denomination's history. It is hoped that when the various educators and administrators re view the data about their own organizations, they will notify the Department of Education concerning any corrections and additions. They should please include supporting evidence from as many sources as possible. It is hoped that within the next five to ten years a revised edition may replace this first one. It would contain not only necessary changes, but also would be brought up to date. -

In This Issue

In this Issue: Making sense of makerspaces Thinkers and Tinkers at Scotch Get Caught up in Reading 2014 Library Awards Thoughts from the Professional Journal of the Library Officer’s Desk WA School Library Association Vol. 5, No. 1 May 2015 Contents Editorial Vol. 5, No. 1, 2015 In this edition of ic3, it was decided that the theme would be makerspaces. Maker education has the potential to revolutionise the way we approach teaching and 2. From the President’s Desk learning. School libraries are well positioned to take the lead in this revolution. If we are to remain relevant and 4. WASLA News be considered leaders in education at our schools, it is important that we move out of our comfort zones and 5. Making Sense of Maker Spaces explore new possibilties and ideas. Don’t know what you are doing? Educate yourself. 8. Thinkers and Tinkers at Scotch Attend professional learning opportunities; read blogs, articles and tweets; attend the upcoming WASLA PDs. 9. Makers Bridge the Gap Then jump in a give it a go. Start small and experiment. Jennifer Lightfoot, at Scotch College, did just that. You will be amazed that it doesn’t need to cost very much 11. SpringShare: Australian roadshow and that your students will help you along the way as they will be fascinated in making new things. 12. Get Caught Up Reading You will find some interesting ideas to start your 13. Promoting Primary Industries exploration in this publication. If you are reading it online, you have the advantage of clicking on the hyperlinks to explore further. -

Annual Report 2018 2 Loreto Kirribilli 2018 Annual Report

LORETO KIRRIBILLI ANNUAL REPORT 2018 2 LORETO KIRRIBILLI 2018 ANNUAL REPORT LORETO KIRRIBILLI 85 Carabella Street Kirribilli NSW 2061 Mrs Anna Dickinson Principal Telephone: 02 9957 4722 Email: [email protected] Registered: Kindergarten to Year 12 from 1st January 2019 to 31st December 2023 Accredited: Years 7 to 12 teaching School Certificate and Higher School Certificate from 1st January 2019 to 31st December 2023 LORETO KIRRIBILLI 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 3 TaBLE Of COnTEnTs INTRODUCTION 5 PRINCIPAL’S MESSAGE 6 PHILOSOPHY 8 GOVERNANCE 8 THEME 1: MESSAGE FROM KEY SCHOOL BODIES 9 1 .1 School Board 10 1 .2 Parents and Friends Committee (P&F) 13 1 .3 Senior School Student Representative Council 15 THEME 2: CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL 16 THEME 3: STUDENT OUTCOMES IN STANDARDISED NATIONAL LITERACY & NUMERACY TESTING 18 3 .1 Junior School: Kindergarten to Year 6 NAPLAN Results 19 3 .2 Senior School: Years 7 to 12 NAPLAN Results 22 THEME 4: SENIOR SECONDARY OUTCOMES 25 4 .1 Record of Student Achievement Years 10 to 11 26 4 .2 Higher School Certificate 26 THEME 5: TEACHER PROFESSIONAL LEARNING, QUALIFICATIONS & ACCREDITATION 30 5 .1 Junior School Professional Development 31 5 .2 Senior School Professional Development 32 5. 3 Teacher Qualifications 34 5. 4 Teacher Accreditation 34 THEME 6: WORKFORCE COMPOSITION 35 4 LORETO KIRRIBILLI 2018 ANNUAL REPORT THEME 7: STUDENT ATTENDANCE & RETENTION RATES & POST SCHOOL DESTINATIONS IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS 37 7 .1 Student Attendance Rates 38 7 .2 Student Retention Rates 38 7 .3 Post-School Destinations -

Prospectus We Focus on Developing the Whole Person – Intellectually, Physically, Socially, Emotionally and Dr Timothy Petterson Spiritually

Shore Prospectus We focus on developing the whole person – intellectually, physically, socially, emotionally and Dr Timothy Petterson spiritually. The Headmaster Shore was established in 1889 as a leading comprehensive school for the education of boys. In 2003 we also welcomed girls to our Early Learning Centre and Kindergarten, Year 1 and Year 2 facility at the Northbridge Campus. Our rich history and traditions have powerfully shaped our School, fostering a sense of community and belonging. Reflecting Shore’s Christian foundations, we focus on developing the whole person – intellectually, physically, socially, emotionally and spiritually. We place a strong emphasis on character formation, challenging our students to be responsible citizens of integrity who seek to serve the wider community. Our commitment to a truly comprehensive education means we pursue engaged rigour in academic work, and also offer a wide range of learning experiences, both in and out of the classroom. We create a genuine partnership between the School and home, enabling each student to discover their individual talents and preparing them for the realities and challenges of our contemporary world. We believe the best evidence of success will be exhibited in the adult lives of those who have passed through the School. We are proud of our many Old Boys who have served in all walks of life with great dedication. I am delighted to extend an invitation to you to visit Shore and explore all that a Shore education has to offer. School motto Vitai Lampada Tradunt Dr Timothy Petterson Headmaster The motto from Lucretius, translates ‘They hand on the Torch of Life’. -

Good Hope School Annual Report 2019-2020

GOOD HOPE SCHOOL ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Good Hope School, 303 Clear Water Bay Road, Kowloon Tel: (852) 2321 0250 Fax: (852) 2324 8242 Page 1 of 18 School Annual Report for 2019-20 CONTENTS School Information Pg. 3 - 9 Report – Priorities Pg. 10 - 17 Financial Report Pg. 18 Page 2 of 18 School Annual Report for 2019-20 Introduction GOOD HOPE is a Catholic school sponsored by the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception (MIC), originally established as a Kindergarten on Waterloo Road in 1954. In 1955, the Primary School opened at its current location on Clear Water Bay Road. The Secondary School accepted its first Secondary 1 students in 1957. These students sat their HKCE Examination in 1962. Good Hope School Secondary Section grew to its current size of 36 classes in 1975. The Secondary Section became fully subsidized under the Hong Kong Education Department in 1978 and since 2002 the school has been operating under the Direct Subsidy Scheme, which allows greater flexibility for the school to provide quality education. Mission Statement Good Hope School puts special emphasis on the Christian values of Love, Hope, Joy and Thanksgiving. Through a whole-school approach we aim to draw out the potential and foster the sense of uniqueness of each student. We are committed to providing all Good Hopers with equal opportunities to develop their spiritual, moral, intellectual, physical, social, emotional and aesthetic dimensions. We accept the call to facilitate the formation of graceful, reflective young women who have a global perspective and are mindful of both their responsibilities of citizenship and their capability of making a difference. -

Enhanced Student Information System (ESIS) ESIS Data Dictionary

Enhanced Student Information System (ESIS) ESIS Data Dictionary First Edition How to obtain more information Specific inquiries about this product and related statistics or services should be directed to: Client Services, Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0T6 (telephone: (613) 951-7608; toll free at 1 800 307-3382; by fax at (613) 951-9040; or e-mail: [email protected]). For information on the wide range of data available from Statistics Canada, you can contact us by calling one of our toll-free numbers. You can also contact us by e-mail or by visiting our Web site. National inquiries line 1 800 263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1 800 363-7629 E-mail inquiries [email protected] Web site www.statcan.ca Ordering information This product, is available on the Internet for free. Users can obtain single issues at: http://www.statcan.ca/english/sdds/5017.htm Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner and in the official language of their choice. To this end, the Agency has developed standards of service which its employees observe in serving its clients. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll free at 1 800 263-1136. Enhanced Student Information System (ESIS) ESIS Data Dictionary Note of appreciation Canada owes the success of its statistical system to a long-standing partnership between Statistics Canada, the citizens of Canada, its businesses, governments and other institutions. -

School Personnel

LORETO NEDLANDS Inspired – Confident - Compassionate 2021 Parent Handbook CONTENTS Loreto Nedlands Mission Statement 3 Loreto Schools of Australia Mission Statement 4 Loreto Brief History 4 Crest and Motto 5 Houses 5 School Board 5 Principal Address 6 School Personnel 7 Term Dates 8 Class Times 9 Arrival and Pick Up Times 9 After School Play 9 Office 10 Out of School Hours Care 10 Parent Information and Emergency Contact Details 10 Communication 11 Newsletter 11 Messages to Children 11 Late Arrivals 11 Absences 11 Leaving School Grounds 11 Family Detail Forms and Emergency Contact Numbers 11 Parent Involvement at Loreto Nedlands 11 Parents and Friends (P&F) 11 Class Parent Representatives (CPR) 11 Parent Volunteers 12 Canteen 12 Assemblies 12 Booklists 12 Insurance 12 Parent Code of Conduct 12 Pupil Free Days and Public Holidays 13 Emergency Evacuation 13 Toys and Games 13 Mobile Phones 13 Library 13 Music 13 Physical Education 13 Performing Arts 14 Camps 14 Excursions 14 Homework 14 Golden Rules 15 Administration of Medication 16 Allergy Aware Policy 17 Treats and Birthday Food 17 Dogs on School Grounds 17 Communicable Diseases (Health Department of WA) 17 Recommended Minimum Exclusion Periods from School 18 Student Drop-Off and Pick-Up Zones 18 Parking 19 Uniform Shop 20 Hairstyles/ Jewellery 20 Lost Property 20 Uniforms 20-21 2 Loreto Nedlands Mission Statement Loreto Nedlands creates empowered thinkers who are inspired to excel, feel confident to lead and show compassion as they serve others in the spirit of Mary Ward. Inspired. Confident. Compassionate. School Prayer May Mary Ward our founder Guide us to faith and love in you. -

List AWS Educate Institutions

Educate Institution City Country 1337 KHOURIBGA Morocco 1daoyun 无锡 China 3aaa Apprenticeships Derby United Kingdom 3W Academy Paris France 42 São Paulo sao paulo Brazil 42 seoul seoul Korea, Republic of 42 Tokyo Minato-ku Tokyo Japan 42Quebec QUEBEC Canada A P Shah Institute of Technology Thane West India A. D. Patel Institute of Technology Ahmedabad India A.V.C. College of Engineering Mayiladuthurai India Aalim Muhammed Salegh College of Engineering Avadi-IAF India Aaniiih Nakoda College Harlem United States AARHUS TECH Aarhus N Denmark Aarhus University Aarhus Denmark Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology Kanchipuram(Dt) India Abb Industrigymansium Västerås Sweden Abertay University Dundee United Kingdom ABES Engineering College Ghaziabad India Abilene Christian University Abilene United States Research Pune Pune India Abo Akademi University Turku Finland Academia de Bellas Artes Semillas Ltda Bogota Colombia Academia Desafio Latam Santiago Chile Academia Sinica Taipei Taiwan Academie Informatique Quebec-Canada Lévis Canada Academy College Bloomington United States Academy for Career Exploration PROVIDENCE United States Academy for Urban Scholars Columbus United States ACAMICA Palermo Argentina Accademia di Belle Arti di Cuneo Cuneo Italy Achariya College of Engineering Technology Puducherry India Acharya Institute of Technology Bangalore India Acharya Narendra Dev College New Delhi India Achievement House Cyber Charter School Exton United States Acropolis Institute of Technology & Research, Indore Indore India ACT AMERICAN COLLEGE -

2014 Annual Report and Financial Statements

2014 Annual Report and Financial Statements as presented at the 2015 Annual General Meeting Table of Contents AISWA Strategic Plan 3 Office Bearers 6 Executive Committee Membership 7 Executive Summary 8 AISWA 2014 9 State Issues 16 National Issues 17 Funding 19 Australian Curriculum 20 Aboriginal Independent Community Schools 21 Inclusive Education 22 Industrial Issues 23 Literacy 24 Numeracy 25 Quality Teacher Agenda 26 Statistics 27 List of AISWA Member Schools 28 Audited Financial Statements for Year Ended 31 December 2014 30 Appendices Appendix 1: 2015 Membership Fees Association of Independent Schools of Western Australia (Inc) 2014 Annual Report 2 AISWA Strategic Plan 2010 ‐ 2014 The Association of Independent Schools of Western Australia is the peak body representing Independent schools in Western Australia. It has 158 member schools which enrol over 70,000 students; accounting for over 16% of Western Australian school enrolments. As a sector, Independent schools are diverse in nature. They provide for students of all abilities and all social and ethnic backgrounds. They provide quality schooling for a wide range of communities, including some of Western Australia’s most remote and disadvantaged Indigenous communities, communities in regional towns and diverse communities in Perth. Many member schools espouse a religious or values‐based education, while others promote a particular educational philosophy. They are all registered through the Office of Non‐Government Education. Member schools of the Association are not‐for‐profit and are governed independently. Our Vision For Independent schools to be acknowledged and recognised as valued providers of education in Western Australia. Our Mission To promote a strong Independent sector which offers a high quality education appropriate to the needs of Western Australian children.