Cannabis Use Disorder: Implications and Best Practices by Cameron Duncan, DNP, MS, APRN, FNP-C, PMHNP-BC; Kendra Butler, BSN, RN; and Laurielyn Loa, BSN, RN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning

6 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. Regular cannabis use is associated with mild cognitive difficulties, which are typically not apparent following about one month of abstinence. Heavy (daily) and long-term cannabis use is related to more This is the first in a series of reports noticeable cognitive impairment. that reviews the effects of cannabis • Cannabis use beginning prior to the age of 16 or 17 is one of the strongest use on various aspects of human predictors of cognitive impairment. However, it is unclear which comes functioning and development. This first — whether cognitive impairment leads to early onset cannabis use or report on the effects of chronic whether beginning cannabis use early in life causes a progressive decline in cannabis use on cognitive functioning cognitive abilities. provides an update of a previous report • Regular cannabis use is associated with altered brain structure and function. with new research findings that validate Once again, it is currently unclear whether chronic cannabis exposure and extend our current understanding directly leads to brain changes or whether differences in brain structure of this issue. Other reports in this precede the onset of chronic cannabis use. series address the link between chronic • Individuals with reduced executive function and maladaptive (risky and cannabis use and mental health, the impulsive) decision making are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: a Case Report in Mexico

CASE REPORT Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report in Mexico Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz,1 Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete,3 Emmanuel Solís Ayala,1 Ana de la Fuente-Martín2 1 Medicina Interna, Hospital Ánge- ABSTRACT les Pedregal. 2 Escuela de Medicina, Universi- Background. The first case report on the Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was registered in 2004. dad la Salle. Years later, other research groups complemented the description of CHS, adding that it was associated with 3 Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría such behaviors as chronic cannabis abuse, acute episodes of nausea, intractable vomiting, abdominal pain Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. and compulsive hot baths, which ceased when cannabis use was stopped. Objective. To provide a brief re- view of CHS and report the first documented case of CHS in Mexico. Method. Through a systematic search Correspondence: Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz. in PUBMED from 2004 to 2016, a brief review of CHS was integrated. For the second objective, CARE clinical Medicina Interna, Hospital Ángeles case reporting guidelines were used to register and manage a patient with CHS at a high specialty general del Pedregal. hospital. Results. Until December 2016, a total of 89 cases had been reported worldwide, although none from Av. Periférico Sur 7700, Int. 681, Latin American countries. Discussion and conclusion. Despite the cases reported in the scientific literature, Col. Héroes de Padierna, Del. Magdalena Contreras, C.P. 10700 experts have yet to achieve a comprehensive consensus on CHS etiology, diagnosis and treatment. The lack Ciudad de México. of a comprehensive, standardized CHS algorithm increases the likelihood of malpractice, in addition to con- Phone: +52 (55) 2098-5988. -

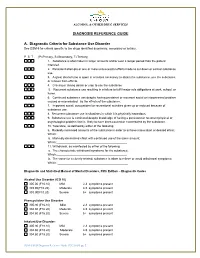

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Mental Health

1 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Mental Health Sarah Konefal, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular cannabis use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. • Regular cannabis use is at least twice as common among individuals with This is the first in a series of reports mental disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depressive and that reviews the effects of cannabis anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). use on various aspects of human • There is strong evidence linking chronic cannabis use to increased risk of developing psychosis and schizophrenia among individuals with a family functioning and development. This history of these conditions. report on the effects of regular • Although smaller, there is still a risk of developing psychosis and cannabis use on mental health provides schizophrenia with regular cannabis use among individuals without a family an update of a previous report with history of these disorders. Other factors contributing to increased risk of new research findings that validate and developing psychosis and schizophrenia are early initiation of use, heavy or extend our current understanding of daily use and the use of products high in THC content. this issue. Other reports in this series • The risk of developing a first depressive episode among individuals who use address the link between regular cannabis regularly is small after accounting for the use of other substances cannabis use and cognitive functioning, and common sociodemographic factors. -

Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use

The Corinthian Volume 20 Article 16 November 2020 Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use Celia G. Imhoff Georgia College and State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Imhoff, Celia G. (2020) "Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use," The Corinthian: Vol. 20 , Article 16. Available at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol20/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Corinthian by an authorized editor of Knowledge Box. LONG-TERM OUTCOMES OF CHRONIC, RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA USE Amidst insistent, nationwide demand for the acceptance of recreational marijuana, many Americans champion the supposedly non-addictive, inconsequential, and creativity-inducing nature of this “casual” substance. However, these personal beliefs lack scientific evidence. In fact, research finds that chronic adolescent and young adult marijuana use predicts a wide range of adverse occupational, educational, social, and health outcomes. Cannabis use disorder is now recognized as a legitimate condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and cannabis dependence is gaining respect as an authentic drug disorder. Some research indicates that medical marijuana can be somewhat effective in treating assorted medical conditions such as appetite in HIV/AIDS patients, neuropathic pain, spasticity and multiple sclerosis, nausea, and seizures, and thus its value to medicine continues to evolve (Atkinson, 2016). However, many studies on medical marijuana produce mixed results, casting doubt on our understanding of marijuana's medicinal properties (Atkinson, 2016; Keehbauch, 2015). -

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome: an Update on the Pathophysiology and Management

REVIEW ARTICLE Annals of Gastroenterology (2020) 33, 571-578 Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome: an update on the pathophysiology and management Abhilash Perisettia, Mahesh Gajendranb, Chandra Shekhar Dasaric, Pardeep Bansald, Muhammad Azize, Sumant Inamdarf, Benjamin Tharianf, Hemant Goyalg University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR; Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso; Kansas City VA Medical Center; Moses Taylor Hospital and Reginal Hospital of Scranton, Scranton, PA; University of Toledo, HO; The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education, Scranton, PA, USA Abstract Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a form of functional gut-brain axis disorder characterized by bouts of episodic nausea and vomiting worsened by cannabis intake. It is considered as a variant of cyclical vomiting syndrome seen in cannabis users especially characterized by compulsive hot bathing/showers to relieve the symptoms. CHS was reported for the first time in 2004, and since then, an increasing number of cases have been reported. With cannabis use increasing throughout the world as the threshold for legalization becomes lower, its user numbers are expected to rise over time. Despite this trend, a strict criterion for the diagnosis of CHS is lacking. Early recognition of CHS is essential to prevent complications related to severe volume depletion. The recent body of research recognizes that patients with CHS impose a burden on the healthcare systems. Understanding the pathophysiology of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) remains central in explaining the clinical features and potential drug targets for the treatment of CHS. The frequency and prevalence of CHS change in accordance with the doses of tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids in various formulations of cannabis. -

MARIJUANA and SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a Historical Perspective and DSM-5 Overview

MARIJUANA AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a historical perspective and DSM-5 overview Introduction Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the Western world and the third most commonly used recreational drug after alcohol and tobacco. According to the World Health Organization, it also is the illicit substance most widely cultivated, trafficked, and used. Although the long-term clinical outcome of marijuana use disorder may be less severe than other commonly used substances, it is by no means a "safe" drug. Sustained marijuana use can have negative impacts on the brain as well as the body. Studies have indicated a link between regular marijuana use and schizophrenia as well as a demonstrated relationship between marijuana use and a higher incidence of lung cancer. Although there are no pharmacological treatments available with a proven impact on marijuana use disorder, there are several types of behavior therapy that may be effective in treating this disorder. Worldwide Use Of Marijuana For a number of years, the United Nations has been compiling annual surveys of worldwide drug use, including cannabis. Reflecting the difficulties and uncertainties associated with developing estimates of the number of people who use drugs (such as the quality of the data gathered and the methodologies used to sample populations), the latest United Nations estimates are presented in ranges, reflecting the lower and upper estimates indicated through the array of surveys ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 1 available. In their 2012 report (covering 2010), the United Nations estimated that between 119.4 and 224.5 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 had used cannabis in the past year, representing between 2.6% and 5.0% of the world’s population.22 In 2014, approximately 22.2 million people ages 12 and up reported using marijuana during the past month. -

1 Public Policy Statement on Cannabis Background Cannabis Is a Plant That Has Been Used for Its Intoxicating Effects for at Leas

Public Policy Statement on Cannabis Background Cannabis is a plant that has been used for its intoxicating effects for at least a century in the United States and for longer in other cultures. It also has a long history of use around the world for purported medical benefits. More than 100 different cannabinoids have been identified in cannabis. The primary intoxicating cannabinoid in cannabis is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The cannabinoid cannabidiol (CBD) has received increasing public attention in recent years; preliminary findings suggest that CBD may be a useful treatment for several medical conditions and it is not reported to be associated with intoxication or addiction, unlike THC.1 In this document, the term “cannabis” is used to describe the plant-based products. When the document refers specifically to individual cannabinoids, they are identified as such. Between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013, the prevalence of past-year cannabis use by U.S. adults increased from 4.1% to 9.5%, respectively, and the prevalence of cannabis use disorder (CUD) nearly doubled.2 Adults and adolescents increasingly view cannabis use as harmless. A 2019 Pew Research Center survey revealed two-thirds of American adults support cannabis legalization, which reflects a steady increase over the past decade.3 However, between 9.3% and 30.6% of American adults who use cannabis have CUD as measured in the largest recent national surveys. Specifically, 9.3% of past-year adult cannabis users met DSM-IV criteria for CUD based on the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).4 2012-2013 data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) showed that 30.6% of past- year cannabis users had DSM-IV CUD.2 Among U.S. -

A Systematic Review and Bayesian Meta‐Analysis of Interventions

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Walsh, H., McNeill, A., Purssell, E. ORCID: 0000-0003-3748-0864 and Duaso, M. (2020). A systematic review and Bayesian meta‐ analysis of interventions which target or assess co‐‐ use of tobacco and cannabis in single or multi substance interventions. Addiction, 115(10), pp. 1800-1814. doi: 10.1111/add.14993 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/23622/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.14993 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Walsh Hannah (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-1638-1050) McNeill Ann (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-6223-4000) Duaso Maria (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-4801-2954) A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis of interventions which target or assess co-use of -

Acute and Long-Term Effects of Cannabis Use: a Review

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] Current Pharmaceutical Design, 2014, 20, 000-000 1 Acute and Long-Term Effects of Cannabis Use: A Review Laurent Karila1,*, Perrine Roux2, Benjamin Rolland3, Amine Benyamina4, Michel Reynaud4, Henri-Jean Aubin4 and Christophe Lançon5 1Addiction Research and Treatment Center, Paul Brousse Hospital, Paris Sud-11 University, AP-HP, INSERM-CEA U1000, Villejuif, France; 2INSERM U912 (SESSTIM), Université Aix Marseille, IRD, UMR-S912, ORS PACA, Observatoire Régional de la Santé Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, Marseille, France; 3Department of Addiction Medicine, CHU Lille; EA1046, Univ Lille Nord de France, Lille, France; 4Addiction Research and Treatment Center, Paul Brousse Hospital, Paris Sud-11 University, AP-HP, Villejuif, France; 5Psychiatry and Addictology Department, AP-HM, Marseille, France Abstract: Cannabis remains the most commonly used and trafficked illicit drug in the world. Its use is largely concentrated among young people (15- to 34-year-olds). There is a variety of cannabis use patterns, ranging from experimental use to dependent use. Men are more likely than women to report both early initiation and frequent use of cannabis. Due to the high prevalence of cannabis use, the impact of cannabis on public health may be significant. A range of acute and chronic health problems associated with cannabis use has been identi- fied. Cannabis can frequently have negative effects in its users, which may be amplified by certain demographic and/or psychosocial factors. Acute adverse effects include hyperemesis syndrome, impaired coordination and performance, anxiety, suicidal ideations/tendencies, and psychotic symptoms. Acute cannabis consumption is also associated with an increased risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially fatal col- lisions. -

ASAM Issues New Public Policy Statement on Cannabis

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 13, 2020 Media Contact Rebecca Reid 410-212-3843 [email protected] ASAM Issues New Public Policy Statement on Cannabis Nation’s leading association of addiction specialist physicians and other clinicians issues new policy recommendations to protect public health and mitigate the risks of cannabis use Rockville, MD – In a new public policy statement on cannabis, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) reviews the medical and social science literature about cannabis use and recommends important, evidence-based policy changes that mitigate potential harm related to cannabis use in the United States. As the medical community continues to document evidence of the harms and potential benefits of cannabis use, ASAM calls for the decriminalization of cannabis use, alongside appropriate regulations and oversight that protect public health. “Today’s public policy statement recognizes that our country’s historically punitive approach to cannabis use has caused significant harms—especially to persons of color, who are disproportionately arrested and incarcerated for cannabis possession and use,” said Paul H. Earley, MD, DFASAM, president of ASAM. “We must safeguard against the potential harms of cannabis use such as cannabis use disorder, while also recognizing that criminalization is not a constructive way to promote public health.” The new statement makes several recommendations regarding cannabis used for medical purposes, including: Cannabis used for medical purposes should be rescheduled from Schedule 1 of the Controlled Substances Act to promote more clinical research and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversight. Cannabis and cannabis-derived products recommended for medical indications should be subject to FDA review and approval to ensure their safety and effectiveness.