CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES for MANAGEMENT of CANNABIS DEPENDENCE Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning

6 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. Regular cannabis use is associated with mild cognitive difficulties, which are typically not apparent following about one month of abstinence. Heavy (daily) and long-term cannabis use is related to more This is the first in a series of reports noticeable cognitive impairment. that reviews the effects of cannabis • Cannabis use beginning prior to the age of 16 or 17 is one of the strongest use on various aspects of human predictors of cognitive impairment. However, it is unclear which comes functioning and development. This first — whether cognitive impairment leads to early onset cannabis use or report on the effects of chronic whether beginning cannabis use early in life causes a progressive decline in cannabis use on cognitive functioning cognitive abilities. provides an update of a previous report • Regular cannabis use is associated with altered brain structure and function. with new research findings that validate Once again, it is currently unclear whether chronic cannabis exposure and extend our current understanding directly leads to brain changes or whether differences in brain structure of this issue. Other reports in this precede the onset of chronic cannabis use. series address the link between chronic • Individuals with reduced executive function and maladaptive (risky and cannabis use and mental health, the impulsive) decision making are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. -

Adverse Health Consequences of Cannabis Use a Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and Including the Autumn of 2003

The mission of the National Institute of Public Health Sweden is to promote health and to prevent illness and harm. Its mandate includes the synthesis and dissemination of research findings. This report is a survey of the harmful effects – mental as well as physical – which can arise as a consequence of cannabis use. The author, Jan Ramström, is a psychiatrist with several years’ experience of specialised drug-abuse services. A long-time Head of Clinic in the field of general psychiatry, he has been affiliated with the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare for nine years in the capacity of Scientific Adviser on issues of psychiatry Adverse Health and substance abuse. His previous publications include other reports as well as several textbooks in the field of substance abuse, psychiatry and youth development. Consequences of The report is intended for health-care organisations, information officers such as drugs advisers and drug counsellors, and others Cannabis Use in need of knowledge-based information on the consequences of A Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and cannabis use. including the Autumn of 2003 Jan Ramström national institute of public health – sweden National Institute of Public Health Fax +46 8 449 88 11 Rapport R 2004:46 www.fhi.se Distribution E-mail [email protected] ISSN 1651-8624 SE-120 88 Stockholm Internet www.fhi.se ISBN 91-7257-314-7 Adverse Health Consequences of Cannabis Use A Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and including the Autumn of 2003 Jan Ramström national institute of public health – sweden www.fhi.se © national institute of public health – sweden r 2004:46 issn: 1651-8624 isbn: 91-7257-314-7 cover photo by: sjöberg, www.sjobergbild.se printing: sandvikens tryckeri, sandviken 2004 Table of Contents Foreword ____________________________________________________________ 5 Introduction __________________________________________________________ 7 Part One – General Remarks ____________________________________________ 11 1. -

The Motivational Hallo

THEMATIC REVIEW Theotivational motivationalhallo helloMANNERS MATTER PART 3 THE With its empathic style, motivational interviewing seems the ideal way to engage new clients in treatment, a psychological handshake which avoids gripping too tightly yet subtly steers the patient in the intended direction. And often it is, as long as we avoid deploying a mechanical arm. by Mike Ashton of THE MANNERS MATTER SERIES is about how services has been on reinforcing motivation, an amalgam of Thanks to Bill Miller, Jim can encourage clients to stay and do well by the acknowledging a problem, wanting help, and resolv- McCambridge, Dwayne Simpson, 5 Don Dansereau, Gerard Connors, manner in which they offer treatment. Parts one and ing that treatment is the help you need. and John Witton for their comments. two dealt with practical issues like reminders, trans- Once thought of as something the patient either Thanks also to Bill Miller, Janice port and childcare. Even at this level, more is in- did or did not have, motivation is now seen as a fluid Brown, Terri Moyers, Paul Amrhein, John Baer and Damaris Rohsenow volved: respect; treating people as individuals; state of mind susceptible to influence. Of the ways for help with obtaining and conveying concern and caring. to exert this influence, motivational interviewing is interpreting their work. Though they 6 have enriched it, none bear any From here on, relationship issues take centre by far the best known. It qualifies for this review responsibility for the final text. stage. Relegated by medicine -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: a Case Report in Mexico

CASE REPORT Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report in Mexico Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz,1 Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete,3 Emmanuel Solís Ayala,1 Ana de la Fuente-Martín2 1 Medicina Interna, Hospital Ánge- ABSTRACT les Pedregal. 2 Escuela de Medicina, Universi- Background. The first case report on the Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was registered in 2004. dad la Salle. Years later, other research groups complemented the description of CHS, adding that it was associated with 3 Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría such behaviors as chronic cannabis abuse, acute episodes of nausea, intractable vomiting, abdominal pain Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. and compulsive hot baths, which ceased when cannabis use was stopped. Objective. To provide a brief re- view of CHS and report the first documented case of CHS in Mexico. Method. Through a systematic search Correspondence: Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz. in PUBMED from 2004 to 2016, a brief review of CHS was integrated. For the second objective, CARE clinical Medicina Interna, Hospital Ángeles case reporting guidelines were used to register and manage a patient with CHS at a high specialty general del Pedregal. hospital. Results. Until December 2016, a total of 89 cases had been reported worldwide, although none from Av. Periférico Sur 7700, Int. 681, Latin American countries. Discussion and conclusion. Despite the cases reported in the scientific literature, Col. Héroes de Padierna, Del. Magdalena Contreras, C.P. 10700 experts have yet to achieve a comprehensive consensus on CHS etiology, diagnosis and treatment. The lack Ciudad de México. of a comprehensive, standardized CHS algorithm increases the likelihood of malpractice, in addition to con- Phone: +52 (55) 2098-5988. -

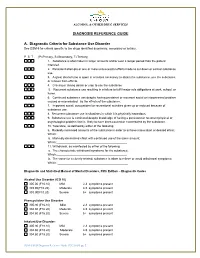

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Mental Health

1 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Mental Health Sarah Konefal, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular cannabis use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. • Regular cannabis use is at least twice as common among individuals with This is the first in a series of reports mental disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depressive and that reviews the effects of cannabis anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). use on various aspects of human • There is strong evidence linking chronic cannabis use to increased risk of developing psychosis and schizophrenia among individuals with a family functioning and development. This history of these conditions. report on the effects of regular • Although smaller, there is still a risk of developing psychosis and cannabis use on mental health provides schizophrenia with regular cannabis use among individuals without a family an update of a previous report with history of these disorders. Other factors contributing to increased risk of new research findings that validate and developing psychosis and schizophrenia are early initiation of use, heavy or extend our current understanding of daily use and the use of products high in THC content. this issue. Other reports in this series • The risk of developing a first depressive episode among individuals who use address the link between regular cannabis regularly is small after accounting for the use of other substances cannabis use and cognitive functioning, and common sociodemographic factors. -

Burke Danielle Final Project 4.14.16 -2

Integrating family systems into substance use treatment Item Type Other Authors Burke, Danielle M. Download date 07/10/2021 22:11:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8035 DocuSign Envelope ID: 22D0C50D-E5D0-47D1-B6D8-920C7825D12F INTEGRATING FAMILY INTO SUBSTANCE USE TREATMENT By Danielle M. Burke * DocuSigned by: Man* WsfliA, RECOMMENDED! V—_ B59EC4405A35447. .. _______________________________ Hilary Wilson, M. A. , DocuSigned by: l/akric &(fyrji 174D4DC2384B4A1... ______________________________ Dr. Valerie Gifford * DocuSigned by: W a-H R .l'h .l'l >5—=S3BE4E3E6248481™ ------------------------------------------------ Dr. Susan Renes, Advisory Committee Chair * DocuSigned by: V a3RF4F3FR94S4fi1__________________________________________________________________ Dr. Susan Renes, Chair School of Education Counseling Program Running Head: FAMILY INTO SUBSTANCE USE TREATMENT 1 Integrating Family Systems into Substance Use Treatment Danielle Burke A Graduate Research Project Submitted to the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Masters of Education, Counseling Presented to Susan Renes, Ph.D. Valerie Gifford, Ph.D. Hilary Wilson, MA, NCSP University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, AK Spring 2016 INTEGRATING FAMILY INTO SUBSTANCE USE TREATMENT 2 Abstract It is important to understand the powerful influence of loved ones in the recovery process. This influence can help encourage substance users to receive treatment, help them remain engaged in treatment, and allow those being treated to receive understanding from their loved ones they might not have received without this treatment component. Providing effective substance use treatment to families should take different aspects into consideration, including family dynamics, cultural aspects, and using the best treatment methods available. Treatment providers may not know how to incorporate social supports into specific treatment interventions. -

Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use

The Corinthian Volume 20 Article 16 November 2020 Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use Celia G. Imhoff Georgia College and State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Imhoff, Celia G. (2020) "Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use," The Corinthian: Vol. 20 , Article 16. Available at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol20/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Corinthian by an authorized editor of Knowledge Box. LONG-TERM OUTCOMES OF CHRONIC, RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA USE Amidst insistent, nationwide demand for the acceptance of recreational marijuana, many Americans champion the supposedly non-addictive, inconsequential, and creativity-inducing nature of this “casual” substance. However, these personal beliefs lack scientific evidence. In fact, research finds that chronic adolescent and young adult marijuana use predicts a wide range of adverse occupational, educational, social, and health outcomes. Cannabis use disorder is now recognized as a legitimate condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and cannabis dependence is gaining respect as an authentic drug disorder. Some research indicates that medical marijuana can be somewhat effective in treating assorted medical conditions such as appetite in HIV/AIDS patients, neuropathic pain, spasticity and multiple sclerosis, nausea, and seizures, and thus its value to medicine continues to evolve (Atkinson, 2016). However, many studies on medical marijuana produce mixed results, casting doubt on our understanding of marijuana's medicinal properties (Atkinson, 2016; Keehbauch, 2015). -

Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders Second Edition WORK GROUP ON SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Herbert D. Kleber, M.D., Chair Roger D. Weiss, M.D., Vice-Chair Raymond F. Anton Jr., M.D. To n y P. G e o r ge , M .D . Shelly F. Greenfield, M.D., M.P.H. Thomas R. Kosten, M.D. Charles P. O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D. Bruce J. Rounsaville, M.D. Eric C. Strain, M.D. Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D. Grace Hennessy, M.D. (Consultant) Hilary Smith Connery, M.D., Ph.D. (Consultant) This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in August 2006. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available in the Psychiatric Practice section of the APA web site at www.psych.org. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. -

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome: an Update on the Pathophysiology and Management

REVIEW ARTICLE Annals of Gastroenterology (2020) 33, 571-578 Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome: an update on the pathophysiology and management Abhilash Perisettia, Mahesh Gajendranb, Chandra Shekhar Dasaric, Pardeep Bansald, Muhammad Azize, Sumant Inamdarf, Benjamin Tharianf, Hemant Goyalg University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR; Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso; Kansas City VA Medical Center; Moses Taylor Hospital and Reginal Hospital of Scranton, Scranton, PA; University of Toledo, HO; The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education, Scranton, PA, USA Abstract Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a form of functional gut-brain axis disorder characterized by bouts of episodic nausea and vomiting worsened by cannabis intake. It is considered as a variant of cyclical vomiting syndrome seen in cannabis users especially characterized by compulsive hot bathing/showers to relieve the symptoms. CHS was reported for the first time in 2004, and since then, an increasing number of cases have been reported. With cannabis use increasing throughout the world as the threshold for legalization becomes lower, its user numbers are expected to rise over time. Despite this trend, a strict criterion for the diagnosis of CHS is lacking. Early recognition of CHS is essential to prevent complications related to severe volume depletion. The recent body of research recognizes that patients with CHS impose a burden on the healthcare systems. Understanding the pathophysiology of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) remains central in explaining the clinical features and potential drug targets for the treatment of CHS. The frequency and prevalence of CHS change in accordance with the doses of tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids in various formulations of cannabis. -

Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs

Medication-Assisted Treatment For Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs A Treatment Improvement Protocol TIP 43 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment MEDICATION- www.samhsa.gov ASSISTED TREATMENT Medication-Assisted Treatment For Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs Steven L. Batki, M.D. Consensus Panel Chair Janice F. Kauffman, R.N., M.P.H., LADC, CAS Consensus Panel Co-Chair Ira Marion, M.A. Consensus Panel Co-Chair Mark W. Parrino, M.P.A. Consensus Panel Co-Chair George E. Woody, M.D. Consensus Panel Co-Chair A Treatment Improvement Protocol TIP 43 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 1 Choke Cherry Road Rockville, MD 20857 Acknowledgments The guidelines in this document should not be considered substitutes for individualized client Numerous people contributed to the care and treatment decisions. development of this Treatment Improvement Protocol (see pp. xi and xiii as well as Appendixes E and F). This publication was Public Domain Notice produced by Johnson, Bassin & Shaw, Inc. All materials appearing in this volume except (JBS), under the Knowledge Application those taken directly from copyrighted sources Program (KAP) contract numbers 270-99- are in the public domain and may be reproduced 7072 and 270-04-7049 with the Substance or copied without permission from SAMHSA/ Abuse and Mental Health Services CSAT or the authors. Do not reproduce or Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department distribute this publication for a fee without of Health and Human Services (DHHS).