MARIJUANA and SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a Historical Perspective and DSM-5 Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smoking Cessation Treatment at Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Programs

SMOKING CEssATION TREATMENT AT SUBSTANCE ABUSE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS Malcolm S. Reid, PhD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; Jeff Sel- zer, MD, North Shore Long Island Jewish Healthcare System; John Rotrosen, MD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry Cigarette smoking is common among persons with drug and alcohol n Nicotine is a highly use disorders, with prevalence rates of 80-90% among patients in sub- addictive substance stance use disorder treatment programs. Such concurrent smoking may that meets all of produce adverse behavioral and medical problems, and is associated the criteria for drug with greater levels of substance use disorder. dependence. CBehavioral studies indicate that the act of cigarette smoking serves as a cue for drug and alcohol craving, and the active ingredient of cigarettes, nicotine, serves as a primer for drug and alcohol abuse (Sees and Clarke, 1993; Reid et al., 1998). More critically, longitudinal studies have found tobacco use to be the number one cause of preventable death in the United States, and also the single highest contributor to mortality in patients treated for alcoholism (Hurt et al., 1996). Nicotine is a highly addictive substance that meets all of the criteria for drug dependence, and cigarette smoking is an especially effective method for the delivery of nicotine, producing peak brain levels within 15-20 seconds. This rapid drug delivery is one of a number of common properties that cigarette smok- ing shares with hazardous drug and alcohol use, such as the ability to activate the dopamine system in the reward circuitry of the brain. -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning

6 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. Regular cannabis use is associated with mild cognitive difficulties, which are typically not apparent following about one month of abstinence. Heavy (daily) and long-term cannabis use is related to more This is the first in a series of reports noticeable cognitive impairment. that reviews the effects of cannabis • Cannabis use beginning prior to the age of 16 or 17 is one of the strongest use on various aspects of human predictors of cognitive impairment. However, it is unclear which comes functioning and development. This first — whether cognitive impairment leads to early onset cannabis use or report on the effects of chronic whether beginning cannabis use early in life causes a progressive decline in cannabis use on cognitive functioning cognitive abilities. provides an update of a previous report • Regular cannabis use is associated with altered brain structure and function. with new research findings that validate Once again, it is currently unclear whether chronic cannabis exposure and extend our current understanding directly leads to brain changes or whether differences in brain structure of this issue. Other reports in this precede the onset of chronic cannabis use. series address the link between chronic • Individuals with reduced executive function and maladaptive (risky and cannabis use and mental health, the impulsive) decision making are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. -

Adverse Health Consequences of Cannabis Use a Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and Including the Autumn of 2003

The mission of the National Institute of Public Health Sweden is to promote health and to prevent illness and harm. Its mandate includes the synthesis and dissemination of research findings. This report is a survey of the harmful effects – mental as well as physical – which can arise as a consequence of cannabis use. The author, Jan Ramström, is a psychiatrist with several years’ experience of specialised drug-abuse services. A long-time Head of Clinic in the field of general psychiatry, he has been affiliated with the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare for nine years in the capacity of Scientific Adviser on issues of psychiatry Adverse Health and substance abuse. His previous publications include other reports as well as several textbooks in the field of substance abuse, psychiatry and youth development. Consequences of The report is intended for health-care organisations, information officers such as drugs advisers and drug counsellors, and others Cannabis Use in need of knowledge-based information on the consequences of A Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and cannabis use. including the Autumn of 2003 Jan Ramström national institute of public health – sweden National Institute of Public Health Fax +46 8 449 88 11 Rapport R 2004:46 www.fhi.se Distribution E-mail [email protected] ISSN 1651-8624 SE-120 88 Stockholm Internet www.fhi.se ISBN 91-7257-314-7 Adverse Health Consequences of Cannabis Use A Survey of Scientific Studies Published up to and including the Autumn of 2003 Jan Ramström national institute of public health – sweden www.fhi.se © national institute of public health – sweden r 2004:46 issn: 1651-8624 isbn: 91-7257-314-7 cover photo by: sjöberg, www.sjobergbild.se printing: sandvikens tryckeri, sandviken 2004 Table of Contents Foreword ____________________________________________________________ 5 Introduction __________________________________________________________ 7 Part One – General Remarks ____________________________________________ 11 1. -

Substance Abuse and Dependence

9 Substance Abuse and Dependence CHAPTER CHAPTER OUTLINE CLASSIFICATION OF SUBSTANCE-RELATED THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES 310–316 Residential Approaches DISORDERS 291–296 Biological Perspectives Psychodynamic Approaches Substance Abuse and Dependence Learning Perspectives Behavioral Approaches Addiction and Other Forms of Compulsive Cognitive Perspectives Relapse-Prevention Training Behavior Psychodynamic Perspectives SUMMING UP 325–326 Racial and Ethnic Differences in Substance Sociocultural Perspectives Use Disorders TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Pathways to Drug Dependence AND DEPENDENCE 316–325 DRUGS OF ABUSE 296–310 Biological Approaches Depressants Culturally Sensitive Treatment Stimulants of Alcoholism Hallucinogens Nonprofessional Support Groups TRUTH or FICTION T❑ F❑ Heroin accounts for more deaths “Nothing and Nobody Comes Before than any other drug. (p. 291) T❑ F❑ You cannot be psychologically My Coke” dependent on a drug without also being She had just caught me with cocaine again after I had managed to convince her that physically dependent on it. (p. 295) I hadn’t used in over a month. Of course I had been tooting (snorting) almost every T❑ F❑ More teenagers and young adults die day, but I had managed to cover my tracks a little better than usual. So she said to from alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents me that I was going to have to make a choice—either cocaine or her. Before she than from any other cause. (p. 297) finished the sentence, I knew what was coming, so I told her to think carefully about what she was going to say. It was clear to me that there wasn’t a choice. I love my T❑ F❑ It is safe to let someone who has wife, but I’m not going to choose anything over cocaine. -

GABA Systems, Benzodiazepines, and Substance Dependence

Robert J. Malcolm GABA Systems, Benzodiazepines, and Substance Dependence Robert J. Malcolm, M.D. Alterations in the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex and GABA neurotransmission influence the reinforcing and intoxicating effects of alcohol and benzodiazepines. Chronic modulation of the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complex plays a major role in central nervous system dysregulation during alcohol abstinence. Withdrawal symptoms stem in part from a decreased GABAergic inhibitory function and an increase in glutamatergic excitatory function. GABAA recep- tors play a role in both reward and withdrawal phenomena from alcohol and sedative-hypnotics. Although less well understood, GABAB receptor complexes appear to play a role in inhibition of moti- vation and diminish relapse potential to reinforcing drugs. Evidence suggests that long-term alcohol use and concomitant serial withdrawals permanently alter GABAergic function, down-regulate ben- zodiazepine binding sites, and in preclinical models lead to cell death. Benzodiazepines have substan- tial drawbacks in the treatment of substance use–related disorders that include interactions with alco- hol, rebound effects, alcohol priming, and the risk of supplanting alcohol dependency with addiction to both alcohol and benzodiazepines. Polysubstance-dependent individuals frequently self-medicate with benzodiazepines. Selective GABA agents with novel mechanisms of action have anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and reward inhibition profiles that have potential in treating substance use and with- drawal and enhancing relapse prevention with less liability than benzodiazepines. The GABAB receptor agonist baclofen has promise in relapse prevention in a number of substance dependence dis- orders. The GABAA and GABAB pump reuptake inhibitor tiagabine has potential for managing alcohol and sedative-hypnotic withdrawal and also possibly a role in relapse prevention. -

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D., M.P.H.; Joseph Guydish, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Jill Williams, M.D.; Marc Steinberg, Ph.D.; and Jonathan Foulds, Ph.D. Despite the high prevalence of tobacco use among people with substance use disorders, tobacco dependence is often overlooked in addiction treatment programs. Several studies and a meta-analytic review have concluded that patients who receive tobacco dependence treatment during addiction treatment have better overall substance abuse treatment outcomes compared with those who do not. Barriers that contribute to the lack of attention given to this important problem include staff attitudes about and use of tobacco, lack of adequate staff training to address tobacco use, unfounded fears among treatment staff and administration regarding tobacco policies, and limited tobacco dependence treatment resources. Specific clinical-, program-, and system-level changes are recommended to fully address the problem of tobacco use among alcohol and other drug abuse patients. KEY WORDS: Alcohol and tobacco; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use, abuse, dependence; addiction care; tobacco dependence; smoking; secondhand smoke; nicotine; nicotine replacement; tobacco dependence screening; tobacco dependence treatment; treatment facility-based prevention; co-treatment; treatment issues; treatment barriers; treatment provider characteristics; treatment staff; staff training; AODD counselor; client counselor interaction; smoking cessation; Tobacco Dependence Program at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey obacco dependence is one of to the other. The common genetic vul stance use was considered a potential the most common substance use nerability may be located on chromo trigger for the primary addiction. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: a Case Report in Mexico

CASE REPORT Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report in Mexico Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz,1 Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete,3 Emmanuel Solís Ayala,1 Ana de la Fuente-Martín2 1 Medicina Interna, Hospital Ánge- ABSTRACT les Pedregal. 2 Escuela de Medicina, Universi- Background. The first case report on the Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was registered in 2004. dad la Salle. Years later, other research groups complemented the description of CHS, adding that it was associated with 3 Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría such behaviors as chronic cannabis abuse, acute episodes of nausea, intractable vomiting, abdominal pain Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. and compulsive hot baths, which ceased when cannabis use was stopped. Objective. To provide a brief re- view of CHS and report the first documented case of CHS in Mexico. Method. Through a systematic search Correspondence: Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz. in PUBMED from 2004 to 2016, a brief review of CHS was integrated. For the second objective, CARE clinical Medicina Interna, Hospital Ángeles case reporting guidelines were used to register and manage a patient with CHS at a high specialty general del Pedregal. hospital. Results. Until December 2016, a total of 89 cases had been reported worldwide, although none from Av. Periférico Sur 7700, Int. 681, Latin American countries. Discussion and conclusion. Despite the cases reported in the scientific literature, Col. Héroes de Padierna, Del. Magdalena Contreras, C.P. 10700 experts have yet to achieve a comprehensive consensus on CHS etiology, diagnosis and treatment. The lack Ciudad de México. of a comprehensive, standardized CHS algorithm increases the likelihood of malpractice, in addition to con- Phone: +52 (55) 2098-5988. -

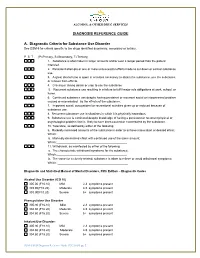

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Substance Use Disorders (SUD) Begin in Childhood Or Adolescence (Kandel, 1992)

PSYCHIATRY TELEHEALTH, LIAISON & CONSULTS (PSYCH TLC) Substance Related Disorders in Children and Adolescents Written and initially reviewed, 11/2011: Zaid Malik, M.D. Deepmala Deepmala, M.D Jody Brown, M.D. Laurence Miller, M.D. Reviewed and updated, 03/04/2014: Deepmala Deepmala, M.D. Work submitted by Contract # 4600016732 from the Division of Medical Services, Arkansas Department of Human Services 1 | P a g e Department of Human Services Psych TLC Phone Numbers: 501-526-7425 or 1-866-273-3835 The free Child Psychiatry Telemedicine, Liaison & Consult (Psych TLC) service is available for: Consultation on psychiatric medication related issues including: . Advice on initial management for your patient . Titration of psychiatric medications . Side effects of psychiatric medications . Combination of psychiatric medications with other medications Consultation regarding children with mental health related issues Psychiatric evaluations in special cases via tele-video Educational opportunities This service is free to all Arkansas physicians caring for children. Telephone consults are made within 15 minutes of placing the call and can be accomplished while the child and/or parent are still in the office. Arkansas Division of Behavioral Health Services (DBHS): (501) 686-9465 http://humanservices.arkansas.gov/dbhs/Pages/default.aspx 2 | P a g e Substance Related Disorders in Children and Adolescents ______________________________________________________ Table of Contents 1. Epidemiology 2. Symptomatology 3. Diagnostic Criteria -- Highlights of Changes from DSM IV to DSM 5 3.1 Substance Use Disorder 3.2 Substance Induced Disorder 3.2.1 Substance Withdrawal 3.2.2 Substance Intoxication 3.2.3 Substance/Medication-Induced Mental Disorders 4. Etiology, Risk Factors and Protective Factors 4.1 Etiology 4.2 Risk Factors and Protective Factors 5. -

Can Tobacco Dependence Provide Insights Into Other Drug Addictions? Joseph R

DiFranza BMC Psychiatry (2016) 16:365 DOI 10.1186/s12888-016-1074-4 DEBATE Open Access Can tobacco dependence provide insights into other drug addictions? Joseph R. DiFranza Abstract Within the field of addiction research, individuals tend to operate within silos of knowledge focused on specific drug classes. The discovery that tobacco dependence develops in a progression of stages and that the latency to the onset of withdrawal symptoms after the last use of tobacco changes over time have provided insights into how tobacco dependence develops that might be applied to the study of other drugs. As physical dependence on tobacco develops, it progresses through previously unrecognized clinical stages of wanting, craving and needing. The latency to withdrawal is a measure of the asymptomatic phase of withdrawal, extending from the last use of tobacco to the emergence of withdrawal symptoms. Symptomatic withdrawal is characterized by a wanting phase, a craving phase, and a needing phase. The intensity of the desire to smoke that is triggered by withdrawal correlates with brain activity in addiction circuits. With repeated tobacco use, the latency to withdrawal shrinks from as long as several weeks to as short as several minutes. The shortening of the asymptomatic phase of withdrawal drives an escalation of smoking, first in terms of the number of smoking days/ month until daily smoking commences, then in terms of cigarettes smoked/day. The discoveries of the stages of physical dependence and the latency to withdrawal raises the question, does physical dependence develop in stages with other drugs? Is the latency to withdrawal for other substances measured in weeks at the onset of dependence? Does it shorten over time? The research methods that uncovered how tobacco dependence emerges might be fruitfully applied to the investigation of other addictions.