Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smoking Cessation Treatment at Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Programs

SMOKING CEssATION TREATMENT AT SUBSTANCE ABUSE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS Malcolm S. Reid, PhD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; Jeff Sel- zer, MD, North Shore Long Island Jewish Healthcare System; John Rotrosen, MD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry Cigarette smoking is common among persons with drug and alcohol n Nicotine is a highly use disorders, with prevalence rates of 80-90% among patients in sub- addictive substance stance use disorder treatment programs. Such concurrent smoking may that meets all of produce adverse behavioral and medical problems, and is associated the criteria for drug with greater levels of substance use disorder. dependence. CBehavioral studies indicate that the act of cigarette smoking serves as a cue for drug and alcohol craving, and the active ingredient of cigarettes, nicotine, serves as a primer for drug and alcohol abuse (Sees and Clarke, 1993; Reid et al., 1998). More critically, longitudinal studies have found tobacco use to be the number one cause of preventable death in the United States, and also the single highest contributor to mortality in patients treated for alcoholism (Hurt et al., 1996). Nicotine is a highly addictive substance that meets all of the criteria for drug dependence, and cigarette smoking is an especially effective method for the delivery of nicotine, producing peak brain levels within 15-20 seconds. This rapid drug delivery is one of a number of common properties that cigarette smok- ing shares with hazardous drug and alcohol use, such as the ability to activate the dopamine system in the reward circuitry of the brain. -

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Prescription Drugs: the Relationship with Illicit Drugs in the Treatment of Substance Users

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author version of an article published as: Teesson, M., Farrugia, P., Mills, K., Hall, W., & Baillie, A. (2012). Alcohol, tobacco, and prescription drugs: The relationship with illicit drugs in the treatment of substance users. Substance use & misuse, Vol. 47, Issue 8-9, p. 963-971. Access to the published version: http://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.663283 Copyright: Copyright the Publisher 2012. Version archived for private and non- commercial use with the permission of the author/s and according to publisher conditions. For further rights please contact the publisher. Comorbidity 1 Alcohol, tobacco and prescription drugs: The relationship with illicit drugs in the treatment of substance users. Maree Teesson, Philippa Farrugia, Katherine Mills 1 Wayne Hall2, Andrew Baillie3. 1. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052 Australia, 2. University of Queensland Centre for Clinical Research, 3. Centre for Emotional Health, Department of Psychology, Macquarie University. * Corresponding author: Maree Teesson National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre University of New South Wales, Sydney New South Wales 2052 Australia Tel: +61 2 9385 0333; fax: +61 2 9385 0222; email: [email protected] Abstract Alcohol, tobacco, prescription drug and illicit drug use frequently co-occur. This paper reviews the extent of this co-occurrence in both general population samples and clinical samples, and its impact on treatment outcome. We argue that the research base for understanding comorbidity between tobacco, alcohol, prescription and illicit drugs needs to be broadened. We specifically advocate for: 1) more epidemiological studies of relationships between alcohol, tobacco and other illicit drug use; and 2) increased research on treatment options that address the problematic use of all of these drugs. -

Concurrent Alcohol and Tobacco Dependence

Concurrent Alcohol and Tobacco Dependence Mechanisms and Treatment David J. Drobes, Ph.D. People who drink alcohol often also smoke and vice versa. Several mechanisms may contribute to concurrent alcohol and tobacco use. These mechanisms include genes that are involved in regulating certain brain chemical systems; neurobiological mechanisms, such as cross-tolerance and cross-sensitization to both drugs; conditioning mechanisms, in which cravings for alcohol or nicotine are elicited by certain environmental cues; and psychosocial factors (e.g., personality characteristics and coexisting psychiatric disorders). Treatment outcomes for patients addicted to both alcohol and nicotine are generally worse than for people addicted to only one drug, and many treatment providers do not promote smoking cessation during alcoholism treatment. Recent findings suggest, however, that concurrent treatment for both addictions may improve treatment outcomes. KEY WORDS: comorbidity; AODD (alcohol and other drug dependence); alcoholic beverage; tobacco in any form; nicotine; smoking; genetic linkage; cross-tolerance; AOD (alcohol and other drug) sensitivity; neurotransmitters; brain reward pathway; cue reactivity; social AODU (AOD use); cessation of AODU; treatment outcome; combined modality therapy; literature review lcohol consumption and tobacco ers who are dependent on nicotine Department of Health and Human use are closely linked behaviors. have a 2.7 times greater risk of becoming Services 1989). The concurrent use of A Thus, not only are people who alcohol dependent than nonsmokers both drugs by pregnant women can drink alcohol more likely to smoke (and (e.g., Breslau 1995). Finally, although also result in more severe prenatal dam- vice versa) but also people who drink the smoking rate in the general popula age and neurocognitive deficits in their larger amounts of alcohol tend to smoke tion has gradually declined over the offspring than use of either drug alone more cigarettes. -

Substance Abuse: the Pharmacy Educator’S Role in Prevention and Recovery

Substance Abuse: The Pharmacy Educator’s Role in Prevention and Recovery Curricular Guidelines for Pharmacy: Substance Abuse and Addictive Disease i Curricular Guidelines for Pharmacy: Substance Abuse and Addictive Disease1,2 BACKGROUND OF THE CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT In 1988, the AACP Special Interest Group (SIG) on Pharmacy Student and Faculty Impairment (renamed Substance Abuse Education and Assistance) undertook the development of curricular guidelines for colleges/schools of pharmacy to facilitate the growth of educational opportunities for student pharmacists. These Curricular Guidelines for Pharmacy Education: Substance Abuse and Addictive Disease were published in 1991 (AJPE. 55:311-16. Winter 1991.) One of the charges of the Special Committee on Substance Abuse and Pharmacy Education was to review and revise the 1991 curricular guidelines. Overall, the didactic and experiential components in the suggested curriculum should prepare the student pharmacist to competently problem-solve issues concerning alcohol and other drug abuse and addictive diseases affecting patients, families, colleagues, themselves, and society. The guidelines provide ten educational goals, while describing four major content areas including: psychosocial aspects of alcohol and other drug use; pharmacology and toxicology of abused substances; identification, intervention, and treatment of people with addictive diseases; and legal/ethical issues. The required curriculum suggested by these guidelines addresses the 1 These guidelines were revised by the AACP Special Committee on Substance Abuse and Pharmacy Education. Members drafting the revised guidelines were Edward M. DeSimone (Creighton University), Julie C. Kissack (Harding University), David M. Scott (North Dakota State University), and Brandon J. Patterson (University of Iowa). Other Committee members were Paul W. Jungnickel, Chair (Auburn University), Lisa A. -

Substance Abuse and Dependence

9 Substance Abuse and Dependence CHAPTER CHAPTER OUTLINE CLASSIFICATION OF SUBSTANCE-RELATED THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES 310–316 Residential Approaches DISORDERS 291–296 Biological Perspectives Psychodynamic Approaches Substance Abuse and Dependence Learning Perspectives Behavioral Approaches Addiction and Other Forms of Compulsive Cognitive Perspectives Relapse-Prevention Training Behavior Psychodynamic Perspectives SUMMING UP 325–326 Racial and Ethnic Differences in Substance Sociocultural Perspectives Use Disorders TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Pathways to Drug Dependence AND DEPENDENCE 316–325 DRUGS OF ABUSE 296–310 Biological Approaches Depressants Culturally Sensitive Treatment Stimulants of Alcoholism Hallucinogens Nonprofessional Support Groups TRUTH or FICTION T❑ F❑ Heroin accounts for more deaths “Nothing and Nobody Comes Before than any other drug. (p. 291) T❑ F❑ You cannot be psychologically My Coke” dependent on a drug without also being She had just caught me with cocaine again after I had managed to convince her that physically dependent on it. (p. 295) I hadn’t used in over a month. Of course I had been tooting (snorting) almost every T❑ F❑ More teenagers and young adults die day, but I had managed to cover my tracks a little better than usual. So she said to from alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents me that I was going to have to make a choice—either cocaine or her. Before she than from any other cause. (p. 297) finished the sentence, I knew what was coming, so I told her to think carefully about what she was going to say. It was clear to me that there wasn’t a choice. I love my T❑ F❑ It is safe to let someone who has wife, but I’m not going to choose anything over cocaine. -

GABA Systems, Benzodiazepines, and Substance Dependence

Robert J. Malcolm GABA Systems, Benzodiazepines, and Substance Dependence Robert J. Malcolm, M.D. Alterations in the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex and GABA neurotransmission influence the reinforcing and intoxicating effects of alcohol and benzodiazepines. Chronic modulation of the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complex plays a major role in central nervous system dysregulation during alcohol abstinence. Withdrawal symptoms stem in part from a decreased GABAergic inhibitory function and an increase in glutamatergic excitatory function. GABAA recep- tors play a role in both reward and withdrawal phenomena from alcohol and sedative-hypnotics. Although less well understood, GABAB receptor complexes appear to play a role in inhibition of moti- vation and diminish relapse potential to reinforcing drugs. Evidence suggests that long-term alcohol use and concomitant serial withdrawals permanently alter GABAergic function, down-regulate ben- zodiazepine binding sites, and in preclinical models lead to cell death. Benzodiazepines have substan- tial drawbacks in the treatment of substance use–related disorders that include interactions with alco- hol, rebound effects, alcohol priming, and the risk of supplanting alcohol dependency with addiction to both alcohol and benzodiazepines. Polysubstance-dependent individuals frequently self-medicate with benzodiazepines. Selective GABA agents with novel mechanisms of action have anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and reward inhibition profiles that have potential in treating substance use and with- drawal and enhancing relapse prevention with less liability than benzodiazepines. The GABAB receptor agonist baclofen has promise in relapse prevention in a number of substance dependence dis- orders. The GABAA and GABAB pump reuptake inhibitor tiagabine has potential for managing alcohol and sedative-hypnotic withdrawal and also possibly a role in relapse prevention. -

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

Vol. 1, Issue 1

Methamphetamine Topical Brief Series: Vol. 1, Issue 1 What is countries involved in World War II provided amphetamine to soldiers Methamphetamine? for performance enhancement and the drug was used by “actors, artists, Methamphetamine is an addictive, athletes, politicians, and the public stimulant drug that affects the alike.”5 central nervous system. It is typically used in powder or pill form and can By the 1960s, media coverage be ingested orally, snorted, smoked, began drawing simplistic, negative or injected. Methamphetamine is connections between amphetamine known as meth, blue, ice, speed, and and crime, and government officials 1 crystal among other names. The term discussed public safety and drugs amphetamine has been used broadly as a social concern.6 Over-the- to refer to a group of chemicals that counter amphetamines were have similar, stimulating properties available until 1959,7 and by 1970 and methamphetamine is included in all amphetamines were added to 2 this group. According to the National the controlled substances list as Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Schedule II drugs. Schedule II drugs “Methamphetamine differs from required a new prescription with amphetamine in that, at comparable each fill and strict documentation doses, much greater amounts of the by doctors and pharmacists.8 drug get into the brain, making it a The reduction in a legal supply 3 more potent stimulant.” of amphetamine led to increased black-market production and sale From the 1930s to the 1960s, of various types of amphetamine U.S. pharmaceutical -

Cocaine Use Disorder

COCAINE USE DISORDER ABSTRACT Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem. Millions of Americans regularly use cocaine, and some develop a substance use disorder. Cocaine is generally not ingested, but toxicity and death from gastrointestinal absorption has been known to occur. Medications that have been used as substitution therapy for the treatment of a cocaine use disorder include amphetamine, bupropion, methylphenidate, and modafinil. While pharmacological interventions can be effective, a recent review of pharmacological therapy for cocaine use indicates that psycho-social efforts are more consistent over medication as a treatment option. Introduction Cocaine is an illicit, addictive drug that is widely used. Cocaine addiction is a serious public health problem that burdens the healthcare system and that can be destructive to individual lives. It is impossible to know with certainty the extent of use but data from public health surveys, morbidity and mortality reports, and healthcare facilities show that there are millions of Americans who regularly take cocaine. Cocaine intoxication is a common cause for emergency room visits, and it is one drug that is most often involved in fatal overdoses. Some cocaine users take the drug occasionally and sporadically but as with every illicit drug there is a percentage of people who develop a substance use disorder. Treatment of a cocaine use disorder involves psycho-social interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com Pharmacology of Cocaine Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the Erthroxylum coca plant, a plant that is indigenous to South America and several other parts of the world, and is cultivated elsewhere. -

Alcohol Use Disorder

Section: A B C D E Resources References Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) Tool This tool is designed to support primary care providers (family physicians and primary care nurse practitioners) in screening, diagnosing and implementing pharmacotherapy treatments for adult patients (>18 years) with Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). Primary care providers should routinely offer medication for moderate and severe AUD. Pharmacotherapy alone to treat AUD is better than no therapy at all.1 Pharmacotherapy is most effective when combined with non-pharmacotherapy, including behavioural therapy, community reinforcement, motivational enhancement, counselling and/or support groups. 2,3 TABLE OF CONTENTS pg. 1 Section A: Screening for AUD pg. 7 Section D: Non-Pharmacotherapy Options pg. 4 Section B: Diagnosing AUD pg. 8 Section E: Alcohol Withdrawal pg. 5 Section C: Pharmacotherapy Options pg. 9 Resources SECTION A: Screening for AUD All patients should be screened routinely (e.g. annually or when indicators are observed) with a recommended tool like the AUDIT. 2,3 It is important to screen all patients and not just patients eliciting an index of suspicion for AUD, since most persons with AUD are not recognized. 4 Consider screening for AUD when any of the following indicators are observed: • After a recent motor vehicle accident • High blood pressure • Liver disease • Frequent work avoidance (off work slips) • Cardiac arrhythmia • Chronic pain • Rosacea • Insomnia • Social problems • Rhinophyma • Exacerbation of sleep apnea • Legal problems Special Patient Populations A few studies have reviewed AUD in specific patient populations, including youth, older adults and pregnant or breastfeeding patients. The AUDIT screening tool considered these populations in determining the sensitivity of the tool. -

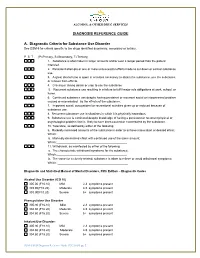

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Drug Use and Gender

Drug Use and Gender Tammy L. Anderson, Ph.D. University of lllinois, Chicago, lL GENDER DIFFERENCES IN study-report a greater occurrence ofillicit substance use DRUG USE AND ABUSE among males than among females. Both surveys have consistently documented this pattern over the years. Looking at the world through a "gender lens" began According to the 1997 NHSDA survey, men reported a in most areas of social science during the second wave of higher rate of illicit substance use (any illicit drug) than the women's movement, or the late 1960s through the women, 8.5 percent to 4.5 percent, nearly double. Men 1970s. During this time feminist researchers began report higher rates of cocaine use .9 percent versus .5 questioning science's conclusions by pointing to percent. alcohol use (58 percent versus 45 percent), binge male-oriented biases in research questions, hypotheses, drinking (23 percent versus 8 percent), and heavy drinking and designs. (8.7 percent versus 2.1 percent). The same pattern was Unfortunately, the "gender lens" did not appear in observed in marijuana use (Office of Applied Studies substance use research until the early 1980s. Prior to the [OAS] tee7). 1970s, most studies of alcohol and other drug use were Johnston. O'Malley, and Bachman (1997) the conducted among males. Early studies that included at University of Michigan yearly women suffered from the "add women and stir compile data on the substance use of 8th. 10th, and 12th graders, college students, approach." Females were added to samples, but no and young adults in the MTF study.