The Coâ•'Occurring Use and Misuse of Cannabis and Tobacco: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smoking Cessation Treatment at Substance Abuse Rehabilitation Programs

SMOKING CEssATION TREATMENT AT SUBSTANCE ABUSE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS Malcolm S. Reid, PhD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry; Jeff Sel- zer, MD, North Shore Long Island Jewish Healthcare System; John Rotrosen, MD, New York University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry Cigarette smoking is common among persons with drug and alcohol n Nicotine is a highly use disorders, with prevalence rates of 80-90% among patients in sub- addictive substance stance use disorder treatment programs. Such concurrent smoking may that meets all of produce adverse behavioral and medical problems, and is associated the criteria for drug with greater levels of substance use disorder. dependence. CBehavioral studies indicate that the act of cigarette smoking serves as a cue for drug and alcohol craving, and the active ingredient of cigarettes, nicotine, serves as a primer for drug and alcohol abuse (Sees and Clarke, 1993; Reid et al., 1998). More critically, longitudinal studies have found tobacco use to be the number one cause of preventable death in the United States, and also the single highest contributor to mortality in patients treated for alcoholism (Hurt et al., 1996). Nicotine is a highly addictive substance that meets all of the criteria for drug dependence, and cigarette smoking is an especially effective method for the delivery of nicotine, producing peak brain levels within 15-20 seconds. This rapid drug delivery is one of a number of common properties that cigarette smok- ing shares with hazardous drug and alcohol use, such as the ability to activate the dopamine system in the reward circuitry of the brain. -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning

6 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Cognitive Functioning Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. Regular cannabis use is associated with mild cognitive difficulties, which are typically not apparent following about one month of abstinence. Heavy (daily) and long-term cannabis use is related to more This is the first in a series of reports noticeable cognitive impairment. that reviews the effects of cannabis • Cannabis use beginning prior to the age of 16 or 17 is one of the strongest use on various aspects of human predictors of cognitive impairment. However, it is unclear which comes functioning and development. This first — whether cognitive impairment leads to early onset cannabis use or report on the effects of chronic whether beginning cannabis use early in life causes a progressive decline in cannabis use on cognitive functioning cognitive abilities. provides an update of a previous report • Regular cannabis use is associated with altered brain structure and function. with new research findings that validate Once again, it is currently unclear whether chronic cannabis exposure and extend our current understanding directly leads to brain changes or whether differences in brain structure of this issue. Other reports in this precede the onset of chronic cannabis use. series address the link between chronic • Individuals with reduced executive function and maladaptive (risky and cannabis use and mental health, the impulsive) decision making are more likely to develop problematic cannabis use and cannabis use disorder. -

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Prescription Drugs: the Relationship with Illicit Drugs in the Treatment of Substance Users

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author version of an article published as: Teesson, M., Farrugia, P., Mills, K., Hall, W., & Baillie, A. (2012). Alcohol, tobacco, and prescription drugs: The relationship with illicit drugs in the treatment of substance users. Substance use & misuse, Vol. 47, Issue 8-9, p. 963-971. Access to the published version: http://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.663283 Copyright: Copyright the Publisher 2012. Version archived for private and non- commercial use with the permission of the author/s and according to publisher conditions. For further rights please contact the publisher. Comorbidity 1 Alcohol, tobacco and prescription drugs: The relationship with illicit drugs in the treatment of substance users. Maree Teesson, Philippa Farrugia, Katherine Mills 1 Wayne Hall2, Andrew Baillie3. 1. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052 Australia, 2. University of Queensland Centre for Clinical Research, 3. Centre for Emotional Health, Department of Psychology, Macquarie University. * Corresponding author: Maree Teesson National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre University of New South Wales, Sydney New South Wales 2052 Australia Tel: +61 2 9385 0333; fax: +61 2 9385 0222; email: [email protected] Abstract Alcohol, tobacco, prescription drug and illicit drug use frequently co-occur. This paper reviews the extent of this co-occurrence in both general population samples and clinical samples, and its impact on treatment outcome. We argue that the research base for understanding comorbidity between tobacco, alcohol, prescription and illicit drugs needs to be broadened. We specifically advocate for: 1) more epidemiological studies of relationships between alcohol, tobacco and other illicit drug use; and 2) increased research on treatment options that address the problematic use of all of these drugs. -

Concurrent Alcohol and Tobacco Dependence

Concurrent Alcohol and Tobacco Dependence Mechanisms and Treatment David J. Drobes, Ph.D. People who drink alcohol often also smoke and vice versa. Several mechanisms may contribute to concurrent alcohol and tobacco use. These mechanisms include genes that are involved in regulating certain brain chemical systems; neurobiological mechanisms, such as cross-tolerance and cross-sensitization to both drugs; conditioning mechanisms, in which cravings for alcohol or nicotine are elicited by certain environmental cues; and psychosocial factors (e.g., personality characteristics and coexisting psychiatric disorders). Treatment outcomes for patients addicted to both alcohol and nicotine are generally worse than for people addicted to only one drug, and many treatment providers do not promote smoking cessation during alcoholism treatment. Recent findings suggest, however, that concurrent treatment for both addictions may improve treatment outcomes. KEY WORDS: comorbidity; AODD (alcohol and other drug dependence); alcoholic beverage; tobacco in any form; nicotine; smoking; genetic linkage; cross-tolerance; AOD (alcohol and other drug) sensitivity; neurotransmitters; brain reward pathway; cue reactivity; social AODU (AOD use); cessation of AODU; treatment outcome; combined modality therapy; literature review lcohol consumption and tobacco ers who are dependent on nicotine Department of Health and Human use are closely linked behaviors. have a 2.7 times greater risk of becoming Services 1989). The concurrent use of A Thus, not only are people who alcohol dependent than nonsmokers both drugs by pregnant women can drink alcohol more likely to smoke (and (e.g., Breslau 1995). Finally, although also result in more severe prenatal dam- vice versa) but also people who drink the smoking rate in the general popula age and neurocognitive deficits in their larger amounts of alcohol tend to smoke tion has gradually declined over the offspring than use of either drug alone more cigarettes. -

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D., M.P.H.; Joseph Guydish, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Jill Williams, M.D.; Marc Steinberg, Ph.D.; and Jonathan Foulds, Ph.D. Despite the high prevalence of tobacco use among people with substance use disorders, tobacco dependence is often overlooked in addiction treatment programs. Several studies and a meta-analytic review have concluded that patients who receive tobacco dependence treatment during addiction treatment have better overall substance abuse treatment outcomes compared with those who do not. Barriers that contribute to the lack of attention given to this important problem include staff attitudes about and use of tobacco, lack of adequate staff training to address tobacco use, unfounded fears among treatment staff and administration regarding tobacco policies, and limited tobacco dependence treatment resources. Specific clinical-, program-, and system-level changes are recommended to fully address the problem of tobacco use among alcohol and other drug abuse patients. KEY WORDS: Alcohol and tobacco; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use, abuse, dependence; addiction care; tobacco dependence; smoking; secondhand smoke; nicotine; nicotine replacement; tobacco dependence screening; tobacco dependence treatment; treatment facility-based prevention; co-treatment; treatment issues; treatment barriers; treatment provider characteristics; treatment staff; staff training; AODD counselor; client counselor interaction; smoking cessation; Tobacco Dependence Program at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey obacco dependence is one of to the other. The common genetic vul stance use was considered a potential the most common substance use nerability may be located on chromo trigger for the primary addiction. -

Is Cannabis Addictive?

Is cannabis addictive? CANNABIS EVIDENCE BRIEF BRIEFS AVAILABLE IN THIS SERIES: ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for youth aged 13–17 years. ` Is cannabis safe to use? Facts for young adults aged 18–25 years. ` Does cannabis use increase the risk of developing psychosis or schizophrenia? ` Is cannabis safe during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding? ` Is cannabis addictive? PURPOSE: This document provides key messages and information about addiction to cannabis in adults as well as youth between 16 and 18 years old. It is intended to provide source material for public education and awareness activities undertaken by medical and public health professionals, parents, educators and other adult influencers. Information and key messages can be re-purposed as appropriate into materials, including videos, brochures, etc. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2018 Publication date: August 2018 This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, provided that it is reproduced for public education purposes and that due diligence is exercised to ensure accuracy of the materials reproduced. Cat.: H14-264/3-2018E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-660-27409-6 Pub.: 180232 Key messages ` Cannabis is addictive, though not everyone who uses it will develop an addiction.1, 2 ` If you use cannabis regularly (daily or almost daily) and over a long time (several months or years), you may find that you want to use it all the time (craving) and become unable to stop on your own.3, 4 ` Stopping cannabis use after prolonged use can produce cannabis withdrawal symptoms.5 ` Know that there are ways to change this and people who can help you. -

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: a Case Report in Mexico

CASE REPORT Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case report in Mexico Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz,1 Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete,3 Emmanuel Solís Ayala,1 Ana de la Fuente-Martín2 1 Medicina Interna, Hospital Ánge- ABSTRACT les Pedregal. 2 Escuela de Medicina, Universi- Background. The first case report on the Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was registered in 2004. dad la Salle. Years later, other research groups complemented the description of CHS, adding that it was associated with 3 Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría such behaviors as chronic cannabis abuse, acute episodes of nausea, intractable vomiting, abdominal pain Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. and compulsive hot baths, which ceased when cannabis use was stopped. Objective. To provide a brief re- view of CHS and report the first documented case of CHS in Mexico. Method. Through a systematic search Correspondence: Luis Fernando García-Frade Ruiz. in PUBMED from 2004 to 2016, a brief review of CHS was integrated. For the second objective, CARE clinical Medicina Interna, Hospital Ángeles case reporting guidelines were used to register and manage a patient with CHS at a high specialty general del Pedregal. hospital. Results. Until December 2016, a total of 89 cases had been reported worldwide, although none from Av. Periférico Sur 7700, Int. 681, Latin American countries. Discussion and conclusion. Despite the cases reported in the scientific literature, Col. Héroes de Padierna, Del. Magdalena Contreras, C.P. 10700 experts have yet to achieve a comprehensive consensus on CHS etiology, diagnosis and treatment. The lack Ciudad de México. of a comprehensive, standardized CHS algorithm increases the likelihood of malpractice, in addition to con- Phone: +52 (55) 2098-5988. -

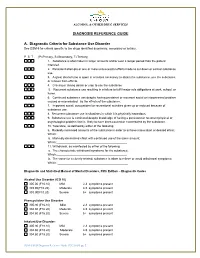

DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance

ALCOHOL & OTHER DRUG SERVICES DIAGNOSIS REFERENCE GUIDE A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorder See DSM-5 for criteria specific to the drugs identified as primary, secondary or tertiary. P S T (P=Primary, S=Secondary, T=Tertiary) 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts and/or over a longer period than the patient intended. 2. Persistent attempts or one or more unsuccessful efforts made to cut down or control substance use. 3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from effects. 4. Craving or strong desire or urge to use the substance 5. Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home. 6. Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problem caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance. 7. Important social, occupational or recreational activities given up or reduced because of substance use. 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous. 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance. 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. Markedly increased amounts of the substance in order to achieve intoxication or desired effect; Which:__________________________________________ b. Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount; Which:___________________________________________ 11. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following: a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for the substance; Which:___________________________________________ b. -

Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis: Regular Use and Mental Health

1 Clearing the Smoke on Cannabis Regular Use and Mental Health Sarah Konefal, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Robert Gabrys, Ph.D., Research and Policy Analyst, CCSA Amy Porath, Ph.D., Director, Research, CCSA Key Points • Regular cannabis use refers to weekly or more frequent cannabis use over a period of months to years. • Regular cannabis use is at least twice as common among individuals with This is the first in a series of reports mental disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depressive and that reviews the effects of cannabis anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). use on various aspects of human • There is strong evidence linking chronic cannabis use to increased risk of developing psychosis and schizophrenia among individuals with a family functioning and development. This history of these conditions. report on the effects of regular • Although smaller, there is still a risk of developing psychosis and cannabis use on mental health provides schizophrenia with regular cannabis use among individuals without a family an update of a previous report with history of these disorders. Other factors contributing to increased risk of new research findings that validate and developing psychosis and schizophrenia are early initiation of use, heavy or extend our current understanding of daily use and the use of products high in THC content. this issue. Other reports in this series • The risk of developing a first depressive episode among individuals who use address the link between regular cannabis regularly is small after accounting for the use of other substances cannabis use and cognitive functioning, and common sociodemographic factors. -

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Pharmacological Management of Substance Abuse, Harmful Use, Addictio

444324 JOP0010.1177/0269881112444324Lingford-Hughes et al.Journal of Psychopharmacology 2012 BAP Guidelines BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, Journal of Psychopharmacology 0(0) 1 –54 harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav recommendations from BAP DOI: 10.1177/0269881112444324 jop.sagepub.com AR Lingford-Hughes1, S Welch2, L Peters3 and DJ Nutt 1 With expert reviewers (in alphabetical order): Ball D, Buntwal N, Chick J, Crome I, Daly C, Dar K, Day E, Duka T, Finch E, Law F, Marshall EJ, Munafo M, Myles J, Porter S, Raistrick D, Reed LJ, Reid A, Sell L, Sinclair J, Tyrer P, West R, Williams T, Winstock A Abstract The British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines for the treatment of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity with psychiatric disorders primarily focus on their pharmacological management. They are based explicitly on the available evidence and presented as recommendations to aid clinical decision making for practitioners alongside a detailed review of the evidence. A consensus meeting, involving experts in the treatment of these disorders, reviewed key areas and considered the strength of the evidence and clinical implications. The guidelines were drawn up after feedback from participants. The guidelines primarily cover the pharmacological management of withdrawal, short- and long-term substitution, maintenance of abstinence and prevention of complications, where appropriate, for substance abuse or harmful use or addiction as well management in pregnancy, comorbidity with psychiatric disorders and in younger and older people. Keywords Substance misuse, addiction, guidelines, pharmacotherapy, comorbidity Introduction guidelines (e.g. -

Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use

The Corinthian Volume 20 Article 16 November 2020 Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use Celia G. Imhoff Georgia College and State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Imhoff, Celia G. (2020) "Long-Term Outcomes of Chronic, Recreational Marijuana Use," The Corinthian: Vol. 20 , Article 16. Available at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol20/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Corinthian by an authorized editor of Knowledge Box. LONG-TERM OUTCOMES OF CHRONIC, RECREATIONAL MARIJUANA USE Amidst insistent, nationwide demand for the acceptance of recreational marijuana, many Americans champion the supposedly non-addictive, inconsequential, and creativity-inducing nature of this “casual” substance. However, these personal beliefs lack scientific evidence. In fact, research finds that chronic adolescent and young adult marijuana use predicts a wide range of adverse occupational, educational, social, and health outcomes. Cannabis use disorder is now recognized as a legitimate condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and cannabis dependence is gaining respect as an authentic drug disorder. Some research indicates that medical marijuana can be somewhat effective in treating assorted medical conditions such as appetite in HIV/AIDS patients, neuropathic pain, spasticity and multiple sclerosis, nausea, and seizures, and thus its value to medicine continues to evolve (Atkinson, 2016). However, many studies on medical marijuana produce mixed results, casting doubt on our understanding of marijuana's medicinal properties (Atkinson, 2016; Keehbauch, 2015). -

Opioid and Nicotine Use, Dependence, and Recovery: Influences of Sex and Gender

Opioid and Nicotine: Influences of Sex and Gender Conference Report: Opioid and Nicotine Use, Dependence, and Recovery: Influences of Sex and Gender Authors: Bridget M. Nugent, PhD. Staff Fellow, FDA OWH Emily Ayuso, MS. ORISE Fellow, FDA OWH Rebekah Zinn, PhD. Health Program Coordinator, FDA OWH Erin South, PharmD. Pharmacist, FDA OWH Cora Lee Wetherington, PhD. Women & Sex/Gender Differences Research Coordinator, NIH NIDA Sherry McKee, PhD. Professor, Psychiatry; Director, Yale Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory Jill Becker, PhD. Biopsychology Area Chair, Patricia Y. Gurin Collegiate Professor of Psychology and Research Professor, Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute, University of Michigan Hendrée E. Jones, Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Executive Director, Horizons, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Marjorie Jenkins, MD, MEdHP, FACP. Director, Medical Initiatives and Scientific Engagement, FDA OWH Acknowledgements: We would like to acknowledge and extend our gratitude to the meeting’s speakers and panel moderators: Mitra Ahadpour, Kelly Barth, Jill Becker, Kathleen Brady, Tony Campbell, Marilyn Carroll, Janine Clayton, Wilson Compton, Terri Cornelison, Teresa Franklin, Maciej Goniewcz, Shelly Greenfield, Gioia Guerrieri, Scott Gottlieb, Marsha Henderson, RADM Denise Hinton, Marjorie Jenkins, Hendrée Jones, Brian King, George Koob, Christine Lee, Sherry McKee, Tamra Meyer, Jeffery Mogil, Ann Murphy, Christine Nguyen, Cheryl Oncken, Kenneth Perkins, Yvonne Prutzman, Mehmet Sofuoglu, Jack Stein, Michelle Tarver, Martin Teicher, Mishka Terplan, RADM Sylvia Trent-Adams, Rita Valentino, Brenna VanFrank, Nora Volkow, Cora Lee Wetherington, Scott Winiecki, Mitch Zeller. We would also like to thank those who helped us plan this program. Our Executive Steering Committee included Ami Bahde, Carolyn Dresler, Celia Winchell, Cora Lee Wetherington, Jessica Tytel, Marjorie Jenkins, Pamela Scott, Rita Valentino, Tamra Meyer, and Terri Cornelison.