Motor Vehicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LABOUR and TECHNOLOGY in the CAR INDUSTRY. Ford Strategies in Britain and Brazil

LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE CAR INDUSTRY. Ford strategies in Britain and Brazil Elizabeth Bortolaia Silva Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD, Imperial College of Science and Technology University of London May 1988 LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE CAR INDUSTRY Ford strategies in Britain and Brazil ABSTRACT This thesis looks at aspects of recent changes in international competition in the car industry. It examines the implications of the changes for the relationship between technology and work and it considers how strategies of multinational corporations interact with different national contexts. It is based on a case-study of the Ford Motor Company in its two largest factories in Britain and Brazil, Dagenham and São Bernardo. Chapter 1 describes existing theoretical approaches to comparative studies of technology and work, criticizes technological and cultural determinist approaches and argues for a method that draws on a 'historical regulation' approach. Chapters 2, 3 and 4 describe the long-term background and recent shifts in the pattern of international competition in the motor industry. In particular they look at important shifts in the late 1970s and 1980s and at Ford's changes in management structure and product strategy designed to meet these challenges. Chapter 5 considers recent debates on international productivity comparisons and presents a fieldwork-based comparison of the production process at Dagenham and São Bernardo. The description shows the importance of issues other than technology in determining the flexibility and quality of production. In different national contexts, 2 different mixes of technology and labour can produce comparable results. Chapters 6, 7 and 8 look at the national and local contexts of industrial relations in the two countries to throw light on the different patterns of change observed in the factories. -

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry Aerospace • KAWASAKI • VOLVO • CATERPILLAR • ADVANCED COATING • KEDDEG COMPANY • XI'AN AIRCRAFT INDUSTRY • CHINA FAW GROUP TECHNOLOGIES GROUP • KOREAN AIRLINES • CHINA INTERNATIONAL Agriculture • AIRBUS MARINE CONTAINERS • L3 COMMUNICATIONS • AIRCELLE • AGRICOLA FORNACE • CHRYSLER • LOCKHEED MARTIN • ALLIANT TECHSYSTEMS • CARGILL • COMMERCIAL VEHICLE • M7 AEROSPACE GROUP • AVICHINA • E. RITTER & COMPANY • • MESSIER-BUGATTI- CONTINENTAL AIRLINES • BAE SYSTEMS • EXOPLAST DOWTY • CONTINENTAL • BE AEROSPACE • MITSUBISHI HEAVY • JOHN DEERE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES • • BELL HELICOPTER • MAUI PINEAPPLE CONTINENTAL • NASA COMPANY AUTOMOTIVE SYSTEMS • BOMBARDIER • • NGC INTEGRATED • USDA COOPER-STANDARD • CAE SYSTEMS AUTOMOTIVE Automotive • • CORNING • CESSNA AIRCRAFT NORTHROP GRUMMAN • AGCO • COMPANY • PRECISION CASTPARTS COSMA INDUSTRIAL DO • COBHAM CORP. • ALLIED SPECIALTY BRASIL • VEHICLES • CRP INDUSTRIES • COMAC RAYTHEON • AMSTED INDUSTRIES • • CUMMINS • DANAHER RAYTHEON E-SYSTEMS • ANHUI JIANGHUAI • • DAF TRUCKS • DASSAULT AVIATION RAYTHEON MISSLE AUTOMOBILE SYSTEMS COMPANY • • ARVINMERITOR DAIHATSU MOTOR • EATON • RAYTHEON NCS • • ASHOK LEYLAND DAIMLER • EMBRAER • RAYTHEON RMS • • ATC LOGISTICS & DALPHI METAL ESPANA • EUROPEAN AERONAUTIC • ROLLS-ROYCE DEFENCE AND SPACE ELECTRONICS • DANA HOLDING COMPANY • ROTORCRAFT • AUDI CORPORATION • FINMECCANICA ENTERPRISES • • AUTOZONE DANA INDÚSTRIAS • SAAB • FLIR SYSTEMS • • BAE SYSTEMS DELPHI • SMITH'S DETECTION • FUJI • • BECK/ARNLEY DENSO CORPORATION -

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance AA AA. General Retailers — GBP 0.25 at close 03 August 2020 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 0.7 140 140 1D WTD MTD YTD 130 130 Absolute 4.6 4.6 4.6 -57.0 0.6 Rel.Sector 2.4 2.4 2.4 -48.8 120 120 Rel.Market 2.5 2.5 2.5 -46.1 110 110 0.5 100 100 VALUATION 90 0.4 90 80 Trailing Relative Price Relative Relative Price Relative 80 70 0.3 PE 1.6 70 Absolute Price (local currency) (local Price Absolute 60 EV/EBITDA 8.0 60 50 0.2 PB -ve 50 40 PCF 0.7 0.1 40 30 Div Yield 2.6 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Price/Sales 0.1 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity - 100 90 90 Div Payout 4.6 90 80 80 ROE - 80 70 70 70 Index) Share Share Sector) Share - - 60 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 40 40 The principal activity of the Company is providing 40 RSI RSI (Absolute) service of consumer roadside assistance. -

The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889-20151

The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889-20151 • JORDI CATALAN Universitat de Barcelona The life cycle of a cluster: some hypotheses Authors such as G. M. P. Swann and E. Bergman have defended the hy- pothesis that clusters have a life cycle.2 During their early history, clusters ben- efit from positive feedback such as strong local suppliers and customers, a pool of specialized labor, shared infrastructures and information externali- ties. However, as clusters mature, they face growing competition in input mar- kets such as real estate and labor, congestion in the use of infrastructures, and some sclerosis in innovation. These advantages and disadvantages combine to create the long-term cycle. In the automobile industry, this interpretation can explain the rise and decline of clusters such as Detroit in the United States or the West Midlands in Britain.3 The objective of this paper is to analyze the life cycle of the Barcelona au- tomobile- industry cluster from its origins at the end of the nineteenth centu- ry to today. The Barcelona district remained at the top of the Iberian auto- mobile clusters for a century. In 2000, when Spain had reached sixth position 1. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the International Conference of Au- tomotive History (Philadelphia 2012), the 16th World Economic History Congress (Stellen- bosch 2012), and the 3rd Economic History Congress of Latin America (Bariloche 2012). I would like to thank the participants in the former meetings for their comments and sugges- tions. This research benefitted from the financial support of the Spanish Ministry of Econo- my (MINECO) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the projects HAR2012-33298 (Cycles and industrial development in the economic history of Spain) and HAR2015-64769-P (Industrial crisis and productive recovery in the Spanish history). -

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

Downfall of Ford in the 70'S

Downfall of Ford in the 70’s Interviewer: Alex Casasola Interviewee: Vincent Sheehy Instructor: Alex Haight Date: February 13, 2013 Table of Contents Interviewee Release Form 3 Interviewer Release Form 4 Statement of Purpose 5 Biography 6 Historical Contextualization 7 Interview Transcription 15 Interview Analysis 35 Appendix 39 Works Consulted 41 Statement of Purpose The purpose of this project was to divulge into the topic of Ford Motor Company and the issues that it faced in the 1970’s through Oral History. Its purpose was to dig deeper into that facts as to why Ford was doing poorly during the 1970’s and not in others times through the use of historical resources and through an interview of someone who experienced these events. Biography Vincent Sheehy was born in Washington DC in 1928. Throughout his life he has lived in the Washington DC and today he resides in Virginia. After graduating from Gonzaga High School he went to Catholic University for college and got a BA in psychology. His father offered him a job into the car business, which was the best offer available to him at the time. He started out a grease rack mechanic and did every job in the store at the Ford on Georgia Ave in the 50’s. He worked as a mechanic in the parts department and became a owner until he handed down the dealership to his kids. He got married to his wife in 1954 and currently has 5 kids. He is interested in golf, skiing and music. When he was younger he participated in the Board of Washington Opera. -

Patrol We Make Promises

NISSAN PATROL WE MAKE PROMISES. WE KEEP PROMISES. INTRODUCING NISSAN ASSURED, IT’S MORE THAN A PROMISE. AS PART OF THE NISSAN FAMILY YOU’RE GUARANTEED OUR COMMITMENT TO CUSTOMER CARE. A LASTING BOND BETWEEN YOU, YOUR VEHICLE AND THE NISSAN BRAND. THAT’S OUR PROMISE. CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE 6 YEAR OR 150 000KM We promise to make your Nissan experience WARRANTY one to cherish, from your delivery day and As long as your car is under our warranty, everyday after, our commitment is to deliver we'll always have you covered if anything a service experience you can trust – and goes wrong. You don’t need to stress for believe in. the first 6 years or 150 000km, whichever CUSTOMER SUPPORT comes first. ROADSIDE ASSISTANCE SERVICE AND REPAIRS We keep you on the road 24/7. Should FREE VEHICLE HEALTH CHECK anything unexpected happen we guarantee We'll give your car a free health check on you 24-hour roadside assistance, no matter every major and minor service prior to any the age of your Nissan, because it’s still a work being carried out, so you know exactly Nissan. Just call 0800 NISSAN (64 77 26) what needs to be done, and how much it anywhere, anytime. Terms and Conditions do apply. will cost. LICENCE RENEWAL REMINDER COMPETITIVELY PRICED PARTS We’ll remind you in advance so you can keep We deliver the highest care for your Nissan your licence disk up to date. by fitting only Nissan Genuine Parts. The expertise of our Nissan trained teams will 3 YEAR OR 90 000KM also guarantee best value-for-money by SERVICE PLAN finding the most competitively priced part For the first 3 years or 90 000km of driving for your local dealer. -

Auto 04 Temp.Qxd

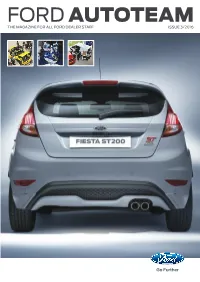

FORD AUTOTEAM THE MAGAZINE FOR ALL FORD DEALER STAFF ISSUE 3/2016 EDITORIAL Changing Times It’s all change for the management team at the Henry Ford Academy. Stuart Harris has moved on to a new position within Ford of Europe and, as I move into his role, I hope to continue with his goal of driving up training standards. Also joining the team is new Academy Principle, Kevin Perks, who brings with him a lifetime of automotive industry experience. Dan Savoury, the new Vice Principal, joined the Academy earlier this year and also has a wealth of industry and training experience that will help us continue to improve our training which, in turn, benefits your business. I hope to use the experience gained in my previous sales and marketing roles within Ford to help our training continue to grow in scope and quality. It is a really exciting time to be a part of the Ford family; with new vehicles joining the range and new technology transforming the industry more widely. Good training is vital to our success and we continue to strive to achieve the highest standards and keep you up to date with this rapidly changing industry, from the technical training for the All-new Ford Mustang detailed on page 4, to ensuring our Commercial Vehicle Sales staff can give their customers the best advice with courses such as Commercial Vehicle Type Approval and Legislation on page 30. The success of our training programmes is demonstrated in this issue, with Chelsea Riddle from TrustFord in Bradford a great example of what the Ford Masters Apprenticeship scheme offers to young people, or the success that Mike Gates from Dinnages Ford in Burgess Hill has achieved with a university scholarship through the Henry Ford Academy. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

Ukraine As Manufacturing Hub

Ukraine as manufacturing hub Boosting value and reaching global market Introduction Yuliya Kovaliv Head of Office, National Investment Council of Ukraine As a result of changes in global geopolitical and international trade contexts, Ukraine emerged on investors’ radars as one of the key manufacturing hubs in Europe. Its beneficial location, well qualified labor force, affordably priced utilities, extensive transport infrastructure, and profound background in manufacturing make the country very attractive for export-oriented businesses. Historically, Ukraine had one of the strongest expertise in machine building among Eastern European and CIS countries. Designed and manufactured in Ukraine, sea vessels and railcars, motor vehicles and aircrafts were used domestically and exported across the world. Ukraine is known as designer and producer of a number of record-breaking machines like AN-225 Mriya – a famous aircraft with the highest carrying capacity and one the largest wingspan in the world. Up till now, expertise remains one of the principle advantages of Ukraine. In 1991, Ukraine gained independence and followed the course of economic reforms. Liberalized markets and free-trade agreements with 46 countries (the last one signed with Israel in January, 2019) resulted in the growing significance of Ukraine as a regional hub and improved its access to the global supply chain. Figures speak for themselves: export volumes in 11 months of 2018 grew by almost 10% and reached $43 billion, with exports to the EU taking over 42%. Now Ukraine is committed to further strengthen its position in the European and global manufacturing industry. For investors, opportunities are vast – from automotive spare parts production and food processing to shipbuilding and aerospace industry. -

Impact of Political Course Shift in Ukraine on Stock Returns

IMPACT OF POLITICAL COURSE SHIFT IN UKRAINE ON STOCK RETURNS by Oleksii Marchenko A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Economic Analysis Kyiv School of Economics 2014 Thesis Supervisor: Professor Tom Coupé Approved by ___________________________________________________ Head of the KSE Defense Committee, Professor Irwin Collier __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Date ___________________________________ Kyiv School of Economics Abstract IMPACT OF POLITICAL COURSE SHIFT IN UKRAINE ON STOCK RETURNS by Oleksii Marchenko Thesis Supervisor: Professor Tom Coupé Since achieving its independence from the Soviet Union, Ukraine has faced the problem which regional block to integrate in. In this paper an event study is used to investigate investors` expectations about winners and losers from two possible integration options: the Free Trade Agreement as a part of the Association Agreement with the European Union and the Custom Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. The impact of these two sudden shifts in the political course on stock returns is analyzed to determine the companies which benefit from each integration decisions. No statistically significant impact on stock returns could be detected. However, our findings suggest a large positive reaction of companies` stock prices to the dismissal of Yanukovych regime regardless of company`s trade orientation and political affiliation. -

Experience and Expertise in Machine Guarding for the Automotive Industry

WELSH AUTOMOTIVE FORUM DIRECTORY OF MEMBER COMPANIES 2016 www.welshautomotiveforum.co.uk WELSH AUTOMOTIVE FORUM DIRECTORY OF MEMBER COMPANIES 2016 3 CONTENTS FOREWORD TIM WILLIAMS, CHIEF EXECUTIVE Welcome to the third edition of the Directory of Welsh Automotive Forum Members. Membership has grown 34% over the past 5 years and I am very pleased that this directory demonstrates the depth and WELSH AUTOMOTIVE FORUM breadth of automotive manufacturing and technical competence of the DIRECTORY OF MEMBER sector in Wales. COMPANIES The Welsh Automotive Forum is the authoritative ‘Voice’ of the sector in Wales and represents the Membership, both nationally and internationally, by working with OEMs, Tier 1s and Government. FOREWORD 3 We have strong relationships with the following bodies: – SMMT, Automotive Council UK, The Automotive Investment Organisation CATEGORIES 4 (AIO), The Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC), The Motorsport Industry Association (MIA), The Niche Vehicle Network (NVN), The Low Carbon A-Z INDEX OF MEMBER COMPANIES 7 Vehicle Partnership (LCVP), the European Centre for Automotive Research (EUCAR) and the European Association of Automotive Suppliers – CLEPA. We also have regular dialogue with equivalent bodies to WAF in the rest of the UK. The growth of the automotive industry in the UK is well documented with the prediction that by 2020, 2million vehicles will be built per annum. For Wales, the announcements in 2016 from Aston Martin and TVR to locate vehicle assembly plants in Wales, generated international interest and further opportunities for the supply chain. The Welsh Automotive Forum has an industry Board which is chaired by Professor Garel Rhys CBE. It is supported by the Welsh Government and is a subsidiary of Industry Wales.