Turquoise, Coral, and Pearl in Sowa Rigpa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in International Buddhist Organizations by the Example of the Organization Rigpa

grant reference number: 01UL1823X The decontextualization of Vajrayāna Buddhism in international Buddhist Organizations by the example of the organization Rigpa Anne Iris Miriam Anders Globalization and commercialization of Buddhism: the organization Rigpa Rigpa is an international Buddhist organization (Vajrayāna Buddhism) with currently 130 centers and groups in 41 countries (see Buddhistische Religionsgemeinschaft Hamburg e.V. c/o Tibetisches Zentrum e.V., Nils Clausen, Hermann-Balk- Str. 106, 22147 Hamburg, Germany : "Rigpa hat mittlerweile mehr als 130 Zentren und Gruppen in 41 Ländern rund um die Welt." in https://brghamburg.de/rigpa-e-v/ date of retrieval: 5.11.2020) Rigpa in Austria: centers in Vienna and Salzburg see https://www.rigpa.de/zentren/daenemark-oesterreich-tschechien/ date of retrieval: 27.10.2020 Rigpa in Germany: 19 centers see https://www.rigpa.de/aktuelles/ date of retrieval: 19.11.2019 Background: globalization, commercialization and decontextualization of (Vajrayāna) Buddhism Impact: of decontextualization of terms and neologisms is the rationalization of economical, emotional and physical abuse of people (while a few others – mostly called 'inner circles' in context - draw their profits) 2 contents of the presentation I. timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa II. testimonies of probands from the organization Rigpa (in the research project TransTibMed) III. impact of decontextualizing concepts of Vajrayāna Buddhism and cross-group neologisms in international Buddhist organizations IV. additional citations in German language V. references 3 I) timeline of crucial incidents in and around the organization Rigpa 1. timeline of crucial events (starting 1994, 2017- summer 2018) (with links to the documents) 2. analysis of decontextualized concepts, corresponding key dynamics and neologisms 3. -

Glossary of Recurrent Tibetan and Sanskrit Terms

GLOSSARY OF RECURRENT TIBETAN AND SANSKRIT TERMS Glossary of Recurrent Tibetan Terms (Except Proper Names) Wylie Transliteration Phonetic English Translation or Defijinition of of Tibetan Terms Transliteration Tibetan Terms of Tibetan Terms ’brug pa bka’ brgyud Drukpa Kagyü a major branch within the Kagyü school of Tibetan Buddhism ’byung ba jungwa element, mostly referring to the fijive elements ’byung ba lnga jungwa nga fijive elements: earth, water, fijire, wind, and space ’byung rtsis jungtsi ‘elemental calculation,’ also known as ‘Chinese divination’ or nag rtsis ’cham cham ritual mask dance ’chi ltas chitä signs of death, death omens ’chi med chime deathlessness ’chi med srog thig chime sogtik ‘Life drop of deathlessness,’ name of a longevity practice of the Nyingma tradition of Dudjom Rinpoche ’chi med tshe yi dngos chime tseyi the siddhi of longevity and grub ngödrup immortality ’khyams pa khyampa ‘wandering,’ a term used to describe the bla when lost; also vagrants that wander around without any fijixed seasonal abode ’pho ba lung powa lung name of an empowerment and a practice regarding the transfer- ence of consciousness at death to a higher realm of existence ’phreng ba trenga rosary am chi amchi Mongolian-derived word for a or or Tibetan medical practitioner, em chi emchi widely used across the Himala- yas bad kan bekan one of the three nyes pa, often translated as ‘phlegm’ Baidūrya dkar po Baidūrya karpo ‘White Beryl,’ the brief title of Desi or Sangye Gyatso’s work on astrol- Baiḍūr dkar po Baidūr karpo ogy, completed in 1685 -

+1. Introduction 2. Cyrillic Letter Rumanian Yn

MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM +1. INTRODUCTION These are comments to "Additional Cyrillic Characters In Unicode: A Preliminary Proposal". I'm examining each section of that document, as well as adding some extra notes (marked "+" in titles). Below I use standard Russian Cyrillic characters; please be sure that you have appropriate fonts installed. If everything is OK, the following two lines must look similarly (encoding CP-1251): (sample Cyrillic letters) АабВЕеЗКкМНОопРрСсТуХхЧЬ (Latin letters and digits) Aa6BEe3KkMHOonPpCcTyXx4b 2. CYRILLIC LETTER RUMANIAN YN In the late Cyrillic semi-uncial Rumanian/Moldavian editions, the shape of YN was very similar to inverted PSI, see the following sample from the Ноул Тестамент (New Testament) of 1818, Neamt/Нямец, folio 542 v.: file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 1 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM Here you can see YN and PSI in both upper- and lowercase forms. Note that the upper part of YN is not a sharp arrowhead, but something horizontally cut even with kind of serif (in the uppercase form). Thus, the shape of the letter in modern-style fonts (like Times or Arial) may look somewhat similar to Cyrillic "Л"/"л" with the central vertical stem looking like in lowercase "ф" drawn from the middle of upper horizontal line downwards, with regular serif at the bottom (horizontal, not slanted): Compare also with the proposed shape of PSI (Section 36). 3. CYRILLIC LETTER IOTIFIED A file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 2 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM I support the idea that "IA" must be separated from "Я". -

The Wittelsbach-Graff and Hope Diamonds: Not Cut from the Same Rough

THE WITTELSBACH-GRAFF AND HOPE DIAMONDS: NOT CUT FROM THE SAME ROUGH Eloïse Gaillou, Wuyi Wang, Jeffrey E. Post, John M. King, James E. Butler, Alan T. Collins, and Thomas M. Moses Two historic blue diamonds, the Hope and the Wittelsbach-Graff, appeared together for the first time at the Smithsonian Institution in 2010. Both diamonds were apparently purchased in India in the 17th century and later belonged to European royalty. In addition to the parallels in their histo- ries, their comparable color and bright, long-lasting orange-red phosphorescence have led to speculation that these two diamonds might have come from the same piece of rough. Although the diamonds are similar spectroscopically, their dislocation patterns observed with the DiamondView differ in scale and texture, and they do not show the same internal strain features. The results indicate that the two diamonds did not originate from the same crystal, though they likely experienced similar geologic histories. he earliest records of the famous Hope and Adornment (Toison d’Or de la Parure de Couleur) in Wittelsbach-Graff diamonds (figure 1) show 1749, but was stolen in 1792 during the French T them in the possession of prominent Revolution. Twenty years later, a 45.52 ct blue dia- European royal families in the mid-17th century. mond appeared for sale in London and eventually They were undoubtedly mined in India, the world’s became part of the collection of Henry Philip Hope. only commercial source of diamonds at that time. Recent computer modeling studies have established The original ancestor of the Hope diamond was that the Hope diamond was cut from the French an approximately 115 ct stone (the Tavernier Blue) Blue, presumably to disguise its identity after the that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier sold to Louis XIV of theft (Attaway, 2005; Farges et al., 2009; Sucher et France in 1668. -

Pearl Accessories Operator's Manual

Pearl® Trilogy Accessories Manual CE Marking: This product (model number 5700-DS) is a CE-marked product. For conformity information, contact LI-COR Support at http://www.licor.com/biotechsupport. Outside of the U.S., contact your local sales office or distributor. Notes on Safety LI-COR products have been designed to be safe when operated in the manner described in this manual. The safety of this product cannot be guaranteed if the product is used in any other way than is specified in this manual. The Pearl® Docking Station and Pearl Clean Box is intended to be used by qualified personnel. Read this entire manual before using the Pearl Docking Station and Pearl Clean Box. Equipment Markings: The product is marked with this symbol when it is necessary for you to refer to the manual or accompanying documents in order to protect against damage to the product. The product is marked with this symbol when a hazardous voltage may be present. Manual Markings: WARNING Warnings must be followed carefully to avoid bodily injury. CAUTION Cautions must be observed to avoid damaging your equipment. NOTE Notes contain additional information and useful tips. IMPORTANT Information of importance to prevent procedural mistakes in the operation of the equipment or related software. Failure to comply may result in a poor experimental outcome but will not cause bodily injury or equipment damage. Federal Communications Commission Radio Frequency Interference Statement WARNING: This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and if not installed in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause interference to radio communications. -

DR. ISAACS ENDS 15 YEARS ·At P9stf: by Irwin Witty Special to the Commentator

' -Good Luck . :. .·:. :. ·-~-- on :. · ~ Finals • .,I. .' ·' •• -- ~ ~ .., ••.,. ~ • Official Undergi:aduate :J~·ewspapef of Yeshiva College •. ,,._/ • : VOLUME XXXYI I NEW YORK CITY, .THURS~AY, JU~E-4, · 1953 . : ,. DR. ISAACS ENDS 15 YEARS ·At P9Stf: By Irwin Witty Special to the Commentator The resignation of Dr. Moses Legis Isaacs, Dean of Y eshitva College, eJ;f ective Sep tember I, 1953, was revealed by Dr. Samuel Belkin, President of:i the-University. Dr. Isaacs' resignation terminates 15 years of teen years. You may i remember that I served as a member of the Executivie Committee of Yeshiva College service as administrator of the College, 11 years I . ., under your chairmanship during the administration of my of which he served in the capacity of dean, and late predecessor, the sainted Dr. Bernard Revel of blessed comes at the end of 25 years of instruction as memory. I say in all sincerity that I never met a man a 01e01her of the college faculty. No im.01ediate more honest, sincere, and self-effacing than you. · successor has been ·named. "I can readily understand, however, thlt a position Dr. Belkin also announced that he expects of a dean-at best-is a very difficult one r;ndeed, it is Dr. Isaacs to remain with the faculty in the ca almo~t ~possible to satisfy a faculty, a student body, and alunµii. • pacity of Professor of Chemistry. "You Will always be remembered in the annals of In his letter to Dr. Is~cs, dated June 1, the Yeshiva College for having been greatly· instrumen~ in president wrote : . -

Speaking Russian

05_149744 ch01.qxp 7/26/07 6:07 PM Page 5 Chapter 1 I Say It How? Speaking Russian In This Chapter ᮣ Understanding the Russian alphabet ᮣ Pronouncing words properly ᮣ Discovering popular expressions elcome to Russian! Whether you want to read Wa Russian menu, enjoy Russian music, or just chat it up with your Russian friends, this is the begin- ning of your journey. In this chapter, you get all the letters of the Russian alphabet, discover the basic rules of Russian pronunciation, and say some popular Russian expressions and idioms. Looking at the Russian Alphabet If you’re like most English speakers, you probably think that the Russian alphabet is the most challenging aspect of picking up the language. But not to worry. The Russian alphabet isn’t as hard as you think. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL From A to Ya: Making sense of Cyrillic The Russian alphabet is based on the Cyrillic alpha- bet, which was named after the ninth-century Byzantine monk, Cyril. But throughout this book, we convert all the letters into familiar Latin symbols, which are the same symbols we use in the English 05_149744 ch01.qxp 7/26/07 6:07 PM Page 6 6 Russian Phrases For Dummies alphabet. This process of converting from Cyrillic to Latin letters is known as transliteration. We list the Cyrillic alphabet here in case you’re adventurous and brave enough to prefer reading real Russian instead of being fed with the ready-to-digest Latin version of it. And even if you don’t want to read the real Russian, check out Table 1-1 to find out what the whole fuss is about regarding the notorious “Russian alphabet.” Notice that, in most cases, a transliterated letter corresponds to the way it’s actually pronounced. -

The Letter to Sogyal (Lakar)

July 14, 2017 Sogyal Lakar, The Rigpa Sangha is in crisis. Long-simmering issues with your behavior can no longer be ignored or denied. As long-time committed and devoted students we feel compelled to share our deep concern regarding your violent and abusive behavior. Your actions have hurt us individually, harmed our fellow sisters and brothers within Rigpa the organization, and by extension Buddhism in the West. We write to you following the advice of the Dalai Lama, in which he has said that students of Tibetan Buddhist lamas are obliged to communicate their concerns about their teacher: If one presents the teachings clearly, others benefit. But if someone is supposed to propagate the Dharma and their behavior is harmful, it is our responsibility to criticize this with a good motivation. This is constructive criticism, and you do not need to feel uncomfortable doing it. In “The Twenty Verses on the Bodhisattvas’ Vows,” it says that there is no fault in whatever action you engage in with pure motivation. Buddhist teachers who abuse sex, power, money, alcohol, or drugs, and who, when faced with legitimate complaints from their own students, do not correct their behavior, should be criticized openly and by name. This may embarrass them and cause them to regret and stop their abusive behavior. Exposing the negative allows space for the positive side to increase. When publicizing such misconduct, it should be made clear that such teachers have disregarded the Buddha’s advice. However, when making public the ethical misconduct of a Buddhist teacher, it is only fair to mention their good qualities as well. -

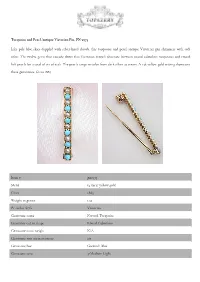

Turquoise and Pearl Antique Victorian Pin, PN-2973 Like Pale Blue Skies

Turquoise and Pearl Antique Victorian Pin, PN-2973 Like pale blue skies dappled with silver-lined clouds, this turquoise and pearl antique Victorian pin shimmers with soft color. The twelve gems that cascade down this Victorian brooch alternate between round cabochon turquoises and round half pearls for a total of six of each. The pearls range in color from dark silver to cream. A 14k yellow gold setting showcases these gemstones. Circa 1885 Item # pn2973 Metal 14 karat yellow gold Circa 1885 Weight in grams 1.22 Period or Style Victorian Gemstone name Natural Turquoise Gemstone cut or shape Round Cabochon Gemstone carat weight N/A Gemstone mm measurements 2.0 Gemstone hue Greenish Blue Gemstone tone 4-Medium Light Gemstone saturation 5-Strong Gemstone # of stones 6 Number of pearls 6 Pearl shape Round Half Pearls Pearl size 2.0 Pearl color Dark Silver White and Cream White Pearl overtone None Other pearl info Natural Half Pearls Length 26.8 mm [1.05 in] Width of widest point 3.66 mm [0.14 in] Important Jewelry Information Each antique and vintage jewelry piece is sent off site to be evaluated by an appraiser who is not a Topazery employee and who has earned the GIA Graduate Gemologist diploma as well as the title of AGS Certified Gemologist Appraiser. The gemologist/appraiser's report is included on the Detail Page for each jewelry piece. An appraisal is not included with your purchase but we are pleased to provide one upon request at the time of purchase and for an additional fee. -

AN Introduction to MUSIC to DELIGHT ALL the SAGES, the MEDICAL HISTORY of DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’

I AN iNTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TO DELIGHT ALL THE SAGES, THE MEDICAL HISTORY OF DRAKKAR TASO TRULKU CHOKYI WANGCRUK (1775-1837)’ STACEY VAN VLEET, Columbia University On the auspicious occasion of theft 50th anniversary celebration, the Dharamsala Men-tsee-khang published a previously unavailable manuscript entitled A Briefly Stated framework ofInstructions for the Glorious field of Medicine: Music to Delight All the Sages.2 Part of the genre associated with polemics on the origin and development of medicine (khog ‘bubs or khog ‘bugs), this text — hereafter referred to as Music to Delight All the Sages — was written between 1816-17 in Kyirong by Drakkar Taso Truilcu Chokyi Wangchuk (1775-1837). Since available medical history texts are rare, this one represents a new source of great interest documenting the dynamism of Tibetan medicine between the 1 $th and early 19th centuries, a lesser-known period in the history of medicine in Tibet. Music to Delight All the Sages presents a historical argument concerned with reconciling the author’s various received medical lineages and traditions. Some 1 This article is drawn from a more extensive treatment of this and related W” and 1 9th century medical histories in my forthcoming Ph.D. dissertation. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Tashi Tsering of the Amnye Machen Institute for sharing a copy of the handwritten manuscript of Music to Delight All the Sages with me and for his encouragement and assistance of this work over its duration. This publication was made possible by support from the Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. -

Plan De Compensación Global Definición De Volúmenes Volume Definitions

Plan de compensación Global www.globalimpacteam.com Definición de Volúmenes www.globalimpacteam.com Volume Definitions ▪ Qualifying Volume - QV ▪ Used to qualify for Ranks ▪ Commissionable Volume - CV ▪ The volume on which commissions are paid ▪ Starter Pack Volume - SV ▪ Volume on enrollment (Starter packs) for Team Bonus calculations ▪ Kyäni Volume – KV ▪ Volume used in calculating Kyäni Care Loyalty Bonus Genealogy Trees Paygate Team Bonus Fast Start Sponsor Bonus Fast Track Generation Matching Car Program Rank Bonus Ranks - Placement Tree, QV Personal Volume Group Volume Volume Outside Volume Outside KYÄNI RANK (QV) (QV) Largest Leg Largest Two Legs Qualified 100 Distributor Garnet 100 300 100 Jade 100 2000 800 Pearl 100 5,000 2,000 Sapphire 100 10,000 4,000 500 Ruby 100 25,000 10,000 1,250 Emerald 100 50,000 20,000 2,500 Diamond 100 100,000 40,000 5,000 Blue Diamond 100 250,000 100,000 12,500 Green Diamond 100 500,000 200,000 25,000 Purple Diamond 100 1,000,000 400,000 50,000 Red Diamond 100 2,000,000 800,000 100,000 Double Red 100 4,000,000 1,600,000 200,000 Diamond Black Diamond 100 10,000,000 4,000,000 500,000 Double Black 100 25,000,000 10,000,000 1,250,000 Diamond Team Bonus Level Payout Paid Level 6 (5% of SV) Team Bonus (Requires Sapphire Rank) Rank Required % of SV Level Distributor/ Paid Level 5 (5% of SV) Level 1 Qualified 25% (Requires Pearl Rank) Distributor Level 2 Garnet 10% Paid Level 4 (5% of SV) (Requires Jade Rank) Level 3 Jade 5% Level 4 Jade 5% Level 5 Pearl 5% Paid Level 3 (5% of SV) (Requires Jade Rank) Sapphire -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible.