The Grieg Journal Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) – Norwegian and European. A critical review By Berit Holth National Library of Norway Edvard Grieg, ca. 1858 Photo: Marcus Selmer Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, Leipzig ca. 1850 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg graduated from The Music Conservatory of Leipzig, 1862 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, 11 year old Alexander Grieg (1806-1875)(father) Gesine Hagerup Grieg (1814-1875)(mother) Cutout of a daguerreotype group. Responsible: Karl Anderson Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway Ole Bull (1810-1880) Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910) Wedding photo of Edvard & Nina Grieg (1845-1935), Copenhagen 1867 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives Edvard & Nina Grieg with friends in Copenhagen Owner: http://griegmuseum.no/en/about-grieg Capital of Norway from 1814: Kristiania name changed to Oslo Edvard Grieg, ca. 1870 Photo: Hansen & Weller Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives. Original in National Library of Norway From Kvam, Hordaland Photo: Reidun Tveito Owner: National Library of Norway Owner: National Library of Norway Julius Röntgen (1855-1932), Frants Beyer (1851-1918) & Edvard Grieg at Løvstakken, June 1902 Owner: Bergen Public Library. Edvard Grieg Archives From Gudvangen, Sogn og Fjordane Photo: Berit Holth Gjendine’s lullaby by Edvard Grieg after Gjendine Slaalien (1871-1972) Owner: National Library of Norway Max Abraham (1831-1900), Oscar Meyer, Nina & Edvard Grieg, Leipzig 1889 Owner: Bergen Public Library. -

Grieg & Musical Life in England

Grieg & Musical Life in England LIONEL CARLEY There were, I would prop ose, four cornerstones in Grieg's relationship with English musicallife. The first had been laid long before his work had become familiar to English audiences, and the last was only set in place shortly before his death. My cornerstones are a metaphor for four very diverse and, you might well say, ve ry un-English people: a Bohemian viol inist, a Russian violinist, a composer of German parentage, and an Australian pianist. Were we to take a snapshot of May 1906, when Grieg was last in England, we would find Wilma Neruda, Adolf Brodsky and Percy Grainger all established as significant figures in English musicallife. Frederick Delius, on the other hand, the only one of thi s foursome who had actually been born in England, had long since left the country. These, then, were the four major musical personalities, each having his or her individual and intimate connexion with England, with whom Grieg established lasting friendships. There were, of course, others who com prised - if I may continue and then finally lay to rest my architectural metaphor - major building blocks in the Grieg/England edifice. But this secondary group, people like Francesco Berger, George Augener, Stop ford Augustus Brooke, for all their undoubted human charms, were firs t and foremost representatives of British institutions which in their own turn played an important role in Grieg's life: the musical establishment, publishing, and, perhaps unexpectedly religion. Francesco Berger (1834-1933) was Secretary of the Philharmonic Soci ety between 1884 and 1911, and it was the Philharmonic that had first prevailed upon the mature Grieg to come to London - in May 1888 - and to perform some of his own works in the capital. -

572258Bk Mozart US 572258Bk Mozart 16/03/2011 17:38 Page 2

572258bk Mozart US_572258bk Mozart 16/03/2011 17:38 Page 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) two children, and he waited several years to reclaim his and lyrical Adagio, which appears less of a contrast. The time, employed by Prince Esterházy, at whose court Kraft the cello. In the same concert, the talented Prague balance of 1000 Gulden from Mozart’s widow. During four other movements are somewhat lighter. The third Joseph Haydn was Kapellmeister. In 1783 Haydn wrote singer!Josepha Duschek sang arias ‘from Figaro and Divertimento in E flat major, K. 563 • String Trio in G major, K. 562e the Napoleonic wars Puchberg lost his fortune, and he movement, a fiery and lively Minuet, is written in the his famous Cello Concerto in D major for Kraft. When Don Juan’. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart never succeeded in autumn of 1788, a work that, unusually, was not died in poverty. manner of a Ländler, an Austrian peasant dance. The Mozart met Anton Kraft in Dresden, he was on a concert The following day Mozart played at court in obtaining the position of Kapellmeister, director of commissioned, but was a present for his friend and Mozart wrote a number of string quartets, but only fourth movement is an air, a song-like Andante, tour with his eleven-year old son Nikolaus Kraft in Dresden the piano concerto later known as the music at any court.!In Vienna the reason undoubtedly fellow-mason!Johann Michael Puchberg (1741-1822), two string trios, and a further one that was unfinished. consisting of a folk-music theme with four variations. -

Neil Thomson — Biografia

Neil Thomson — Biografia Neil Thomson é um dos mais respeitados e versáteis maestros britânicos de sua geração. Nascido em 1966, estudou com Norman Del Mar na Royal College of Music em Londres e mais tarde em Tanglewood, com Leonard Bernstein e Kurt Sanderling. O maestro assume em 2014 a regência titular e direção artística da Orquestra Filarmônica de Goiás. Ele já gravou com a Orquestra Sinfônica de Londres, Orquestra Filarmônica Real de Liverpool e trabalhou nos concertos da Orquestra Filarmônica de Londres, da Philharmonia, da Orquestra Filarmônica da BBC, da Royal Scottish National Orchestra, da Hallé, da Orquestra Filarmônica Real, da Aarhus Symphony Orchestra, da Orquestra do Teatro Massimo em Palermo, Orquestra Sinfônica de Yucatan no México, Romanian Radio Chamber Orchestra e a RTE Concert Orchestra. Em maio de 2005, o maestro foi convidado para reger o concerto em homenagem ao cinquentenário da morte de George Enescu com a Orquestra Nacional da Romênia e os solistas David Geringas e Carmen Oprisanu. Ele fez atualmente estreias bem-sucedidas com a Orquestra Filarmônica de Tóquio, com as Orquestras Sinfônicas de Lahtu e de Oulu na Finlândia, a Royal Northern Sinfonia, a Orquestra Sinfônica de Israel, a Orquestra Sinfonica do Porto Casa da Música, a Orquestra da Rádio WDR, a Koln, Orquestra da Ópera Nacional de Gales, Orchestra of Opera North, a Royal Oman Symphony Orchestra, a Aurora Orchestra e a Nordic Youth Orchestra. Ele tem se apresentado com vários solistas ilustres, como Sir James Galway, Dame Moura Lympany, Sir Thomas Allen, Dame Felicity Lott, Philip Langridge, Sarah Chang, Ittai Shapira, Steven Isserlis, Julian Lloyd Webber, David Geringas, Natalie Clein, Gyorgy Pauk, Brett Dean, Jean-Philippe Collard,Stephen Hough,Peter Jablonski e Sir Richard Rodney Bennett. -

Anders Sveaas' Almennyttige Fond 2017

ÅRSRAPPORT ANDERS SVEAAS’ ALMENNYTTIGE FOND 2017 ASAF ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 1 Interiør fra Kistefos Træsliberi, idag en del av Kistefos-Museet. Foto: Kistefos-Museets bildearkiv Presentasjon 4 Prosjekter vi har støttet i 2017 11 Instrumentene 13 Musikerne 19 Årsberetning 29 Resultatregnskap 34 Balanse 35 Noter 36 English summary 39 Forsiden har utsnitt av portrett av Konsul Anders Sveaas, stifteren av A/S Kistefos Træsliberi. Til høyre hans sønn Advokat Anders Sveaas, far til Christen Sveaas. 2 ASAF ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 ASAF ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 3 Fra Krepselagskonserten 2017. David Coucheron t.v. og Christopher Tun Andersen t.h. Foto: Marte Aubert Presentasjon av Anders Sveaas’ Almennyttige Fond (ASAF) Formålet med fondet er å yte bidrag til allmennyttige og veldedige formål, særlig organisasjoner uten relevant offentlig støtte, og til unge norske musikere, gjennom stipend og utlån av strykeinstrumenter. Fondet ble opp- rettet i 1990 og kunne i 2015 markere 25 års jubileum. Anders Sveaas’ Almennyttige Fond (ASAF) bærer Konsul Anders Sveaas’ navn – stifteren av AS Kistefos Træsliberi i 1889. Styret i ASAF består av Christen Sveaas (styreformann), advokat Carl J. Hambro (viseformann), Annette Vibe Gregersen (forretnings- fører), Torhild Munthe-Kaas og advokat Erik Wahlstrøm. ASAF eier en samling strykeinstrumenter som fortrinnsvis lånes ut til fremstående unge, norske talenter. SØKNADER For søknader til fondet se www.legatsiden.no Skriftlige søknader mottas kun i perioden 1.- 31. mai hvert år. Det finnes ikke eget søknadsskjema. Søknader sendes til Forretningsfører Annette Vibe Gregersen, Dorthes vei 18, 0287 Oslo. E-mail: [email protected] FOR INFORMASJON OM: ASAF, se www.asaf.no Kistefos AS, se www.kistefos.no Kistefos-Museet, se www.kistefos.museum.no Bysten av Konsul Anders Sveaas, stifteren av AS Kistefos Træsliberi AS Kistefos Træsliberi, se www.kistefos-tre.no i 1889, ble laget i 2001 av Nils Aas. -

CHAN 9985 BOOK.Qxd 10/5/07 5:14 Pm Page 2

CHAN 9985 Front.qxd 10/5/07 4:50 pm Page 1 CHAN 9985 CHANDOS CHAN 9985 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 5:14 pm Page 2 Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) Poetic Tone-Pictures, Op. 3 11:45 1 1 Allegro ma non troppo 1:52 2 2 Allegro cantabile 2:19 3 3 Con moto 1:55 4 4 Andante con sentimento 3:17 Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht 5 5 Allegro moderato – Vivo 1:16 6 6 Allegro scherzando 0:49 Sonata, Op. 7 19:41 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur 7 I Allegro moderato – Allegro molto 4:43 8 II Andante molto – L’istesso tempo 4:54 9 III Alla Menuetto, ma poco più lento 3:26 10 IV Finale. Molto allegro – Presto 6:25 Seven fugues for piano (1861–62) 13:29 11 Fuga a 2. Allegro 1:01 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur 12 [Fuga a 2] 1:07 in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeur 13 Fuga a 3. Andante non troppo 2:11 Edvard Grieg in D major • in D-Dur • en ré majeur 14 Fuga a 3. Allegro 1:09 in A minor • in a-Moll • en la mineur 3 CHAN 9985 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 5:14 pm Page 4 Grieg: Sonata, Op. 7 etc. 15 Fuga a 4. Allegro non troppo 2:36 There were two principal strands in Edvard there, and he was followed by an entire in G minor • in g-Moll • en sol mineur Grieg’s creative personality: the piano and cohort of composers-to-be, among them 16 Fuga a 3 voci. -

Download Booklet

MOZART Violin Concertos Nos. 3, 4 and 5 Henning Kraggerud, Violin Norwegian Chamber Orchestra Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Norwegian Chamber Orchestra Violin Concertos Nos. 3, 4 and 5 Photo: Mona Ødegaard Since its formation in 1977 the Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg in 1756, describe as a disgrace to his profession, coarse and dirty. Norwegian Chamber Orchestra has the son of a court musician who, in the year of his Brunetti, a Neapolitan by birth, had been appointed secured a reputation for itself for its youngest child’s birth, published an influential book on Hofmusikdirektor and Hofkonzertmeister in Salzburg in innovative programming and violin-playing. Leopold Mozart rose to occupy the position 1776 and in the following year he succeeded Mozart as creativity. The artistic directors and of Vice-Kapellmeister to the Archbishop of Salzburg, but Konzertmeister, when the latter left the service of the guest leaders of the orchestra have sacrificed his own creative career to that of his son, in Archbishop of Salzburg to seek his fortune in Mannheim included Iona Brown, Leif Ove whom he detected early signs of precocious genius. With and Paris. In 1778 Brunetti had to marry Maria Judith Andsnes, Martin Fröst, François the indulgence of his patron, he was able to undertake Lipps, the sister-in-law of Michael Haydn, who had Leleux and Steven Isserlis together extended concert tours of Europe in which his son and already born him a child. Mozart himself was fastidious with the current artistic director Terje older daughter Nannerl were able to astonish audiences. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

Conference Program 2011

Grieg Conference in Copenhagen 11 to 13 August 2011 CONFERENCE PROGRAM 16.15: End of session Thursday 11 August: 17.00: Reception at Café Hammerich, Schæffergården, invited by the 10.30: Registration for the conference at Schæffergården Norwegian Ambassador 11.00: Opening of conference 19.30: Dinner at Schæffergården Opening speech: John Bergsagel, Copenhagen, Denmark Theme: “... an indefinable longing drove me towards Copenhagen" 21.00: “News about Grieg” . Moderator: Erling Dahl jr. , Bergen, Norway Per Dahl, Arvid Vollsnes, Siren Steen, Beryl Foster, Harald Herresthal, Erling 12.00: Lunch Dahl jr. 13.00: Afternoon session. Moderator: Øyvind Norheim, Oslo, Norway Friday 12 August: 13.00: Maria Eckhardt, Budapest, Hungary 08.00: Breakfast “Liszt and Grieg” 09.00: Morning session. Moderator: Beryl Foster, St.Albans, England 13.30: Jurjen Vis, Holland 09.00: Marianne Vahl, Oslo, Norway “Fuglsang as musical crossroad: paradise and paradise lost” - “’Solveig`s Song’ in light of Søren Kierkegaard” 14.00: Gregory Martin, Illinois, USA 09.30: Elisabeth Heil, Berlin, Germany “Lost Among Mountain and Fjord: Mythic Time in Edvard Grieg's Op. 44 “’Agnete’s Lullaby’ (N. W. Gade) and ‘Solveig’s Lullaby’ (E. Grieg) Song-cycle” – Two lullabies of the 19th century in comparison” 14.30: Coffee/tea 10.00: Camilla Hambro, Åbo, Finland “Edvard Grieg and a Mother’s Grief. Portrait with a lady in no man's land” 14.45: Constanze Leibinger, Hamburg, Germany “Edvard Grieg in Copenhagen – The influence of Niels W. Gade and 10.30: Coffee/tea J.P.E. Hartmann on his specific Norwegian folk tune.” 10.40: Jorma Lünenbürger, Berlin, Germany / Helsinki, Finland 15.15: Rune Andersen, Bjästa, Sweden "Grieg, Sibelius and the German Lied". -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Wednesday 15 February 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall UK PREMIERE: MARK-ANTHONY TURNAGE London’s Symphony Orchestra Mark-Anthony Turnage Håkan (UK premiere, LSO co-commission) INTERVAL Rachmaninov Symphony No 2 John Wilson conductor Håkan Hardenberger trumpet Concert finishes approx 9.30pm Supported by LSO Patrons 2 Welcome 15 February 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican, THE LSO ON TOUR which features the UK premiere of one of two works by Mark-Anthony Turnage co-commissioned by the This month, the LSO will embark on a landmark LSO this season. Håkan is Mark-Anthony Turnage’s tour of the Far East. On 20 February the Orchestra second work for trumpeter Håkan Hardenberger; will open the UK-Korea Year of Culture in Seoul, regular members of the audience will remember the followed by performances in Beijing, Shanghai and LSO’s performance of the first concerto, From the Macau. To conclude the tour, on 4 March the LSO will Wreckage, in 2013. It is a great pleasure to welcome make history by becoming the first British orchestra this collaboration of composer and soloist once again. to perform in Vietnam, conducted by Elim Chan, winner of the 2014 Donatella Flick LSO Conducting The LSO is very pleased to welcome conductor Competition. A trip of this scale is possible thanks to John Wilson for this evening’s performance, and the support of our tour partners. The LSO is grateful is grateful to him for stepping in to conduct at to Principal Partner Reignwood, China Taiping, short notice. -

George Gershwin Soloist: Mike Thomson

Pelly Concert Orchestra ~ 29 January 2011 Welcome to tonight‟s concert which replaces the postponed Christmas Concert. We have altered the programme slightly to reflect the fact that it is no longer the Christmas season and hope you will enjoy the additional pieces such as Copland‟s Rodeo, the Tahiti Trot and Arnold‟s Cornish Dance. Thank you for your support tonight and wishing you a very Happy New Year from all associated with the Pelly. Pelly Concert Orchestra News HMS Pinafore 30 October 2010 The Pelly Orchestra was delighted to have the opportunity to play with Grosvenor Light Opera Company at the end of October. The performance was „from scratch‟ and was semi-staged in St Gabriel‟s Church, Pimlico. This was a new experience for the orchestra and proved that we can adapt ourselves to a new setting and role. It was fun to be part of this vibrant production and the singers enjoyed performing with such an enthusiastic and competent orchestra. Playday 27 February 2011 Come and play with the Pelly Concert Orchestra for the day in February when our third Playday will be taking place at Farnborough Hill. The programme will include: Pictures at an Exhibition – Mussorgsky, The Pines of Rome – Respighi and La Mer – Debussy. To find out more please speak to our bassoonist, Karen Carter, during the interval or send an email to pellyorchestra @hotmail.co.uk. Peter Houghton RIP We were very sorry to hear of the death on 11 November of Peter Houghton who was a Patron and a staunch supporter of the orchestra. -

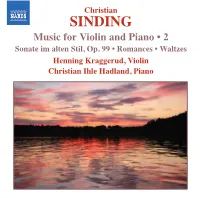

Sinding 2/9/09 10:03 Page 4

572255 bk Sinding 2/9/09 10:03 Page 4 Henning Kraggerud Christian Born in Oslo in 1973, the Norwegian violinist Henning Kraggerud studied with Camilla Wicks and Emanuel Hurwitz and is a recipient of Norway’s prestigious Grieg Prize, the SINDING Ole Bull Prize and the Sibelius Prize. He is a professor at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo, and appears as a soloist with many of the world’s leading orchestras in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. He has enjoyed successful artistic collaborations with many conductors including Marek Janowski, Ivan Fischer, Paavo Music for Violin and Piano • 2 Berglund, Kirill Petrenko, Yakov Kreizberg, Mariss Jansons, Stephane Denève and Kurt Sanderling. A committed chamber musician, Henning Kraggerud also performs Sonate im alten Stil, Op. 99 • Romances • Waltzes both on violin and on viola at major international festivals, collaborating with musicians such as Stephen Kovacevich, Kathryn Stott, Leif Ove Andsnes, Jeffrey Kahane, Truls Mørk and Martha Argerich. His recordings include an acclaimed release of the Henning Kraggerud, Violin complete Unaccompanied Violin Sonatas of Ysaÿe for Simax, and he is a winner of the Spellemann CD Award. His recordings for Naxos include Grieg’s Violin Sonatas (8.553904) and Norwegian Favourites (8.554497) for violin and orchestra. He plays a Christian Ihle Hadland, Piano 1744 Guarneri del Gesù instrument (violin bow: Niels Jørgen Røine, Oslo 2003), provided by Dextra Musica AS, a company founded by Sparebankstiftelsen DnB NOR. Christian Ihle Hadland Christian Ihle Hadland was born in Stavanger in 1983. He received his first lessons at the age of eight and at the age of eleven was enrolled at the Rogaland Music Conservatory, later studying with Jiri Hlinka, the teacher of among others Leif Ove Andsnes, at the Barratt Due Institute of Music in Oslo.