Low Grade Lymphomas in the Elderly*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRF4/DUSP22 Gene Rearrangement by FISH

IRF4/DUSP22 Gene Rearrangement by FISH The IRF4/DUSP22 locus is rearranged in a newly recognized subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement. These lymphomas are uncommon, but are clinically distinct from morphologically similar lymphomas, Tests to Consider including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade follicular lymphoma, and pediatric- type follicular lymphoma. The IRF4/DUSP22 locus is also rearranged in a subset of ALK- IRF4/DUSP22 (6p25) Gene Rearrangement negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL), where this rearrangement is associated by FISH 3001568 with a signicantly better prognosis. Method: Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH) Test is useful in identifying ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphomas and large B- Disease Overview cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement The rearrangement is associated with an improved prognosis Incidence See Related Tests Large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement accounts for <1% of all non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas overall More common in younger patients, with an incidence of 5-6% under age 18 IRF4/DUSP22 rearrangement is found in 30% of ALK-negative ALCLs Symptoms/Findings Large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement typically presents with limited stage disease in the head and neck, while the presentation of ALK-negative ALCLs is variable. Disease-Oriented Information Patients with large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement typically have a favorable outcome after treatment. Rearrangement of the IRF4/DUSP22 locus in ALK-negative ALCL is associated with a better prognosis than ALK-negative ALCL without this rearrangement. Test Interpretation Analytical Sensitivity The limit of detection (LOD) for the IRF4/DUSP22 probe was established by calculating the upper limit of the abnormal signal pattern in normal cells using the Microsoft Excel BETAINV function. -

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular Lymphoma What is follicular lymphoma? Let us explain it to you. www.anticancerfund.org www.esmo.org ESMO/ACF Patient Guide Series based on the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMA: A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS PATIENT INFORMATION BASED ON ESMO CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES This guide for patients has been prepared by the Anticancer Fund as a service to patients, to help patients and their relatives better understand the nature of follicular lymphoma and appreciate the best treatment choices available according to the subtype of follicular lymphoma. We recommend that patients ask their doctors about what tests or types of treatments are needed for their type and stage of disease. The medical information described in this document is based on the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma. This guide for patients has been produced in collaboration with ESMO and is disseminated with the permission of ESMO. It has been written by a medical doctor and reviewed by two oncologists from ESMO including the lead author of the clinical practice guidelines for professionals, as well as two oncology nurses from the European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS). It has also been reviewed by patient representatives from ESMO’s Cancer Patient Working Group. More information about the Anticancer Fund: www.anticancerfund.org More information about the European Society for Medical Oncology: www.esmo.org For words marked with an asterisk, a definition is provided at the end of the document. Follicular Lymphoma: a guide for patients - Information based on ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines – v.2014.1 Page 1 This document is provided by the Anticancer Fund with the permission of ESMO. -

The Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma Center

The Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma Center What Sets Us Apart We provide multidisciplinary • Experienced, nationally and internationally recognized physicians dedicated exclusively to treating patients with lymphoid treatment for optimal survival or plasma cell malignancies and quality of life for patients • Cellular therapies such as Chimeric Antigen T-Cell (CAR T) therapy for relapsed/refractory disease with all types and stages of • Specialized diagnostic laboratories—flow cytometry, cytogenetics, and molecular diagnostic facilities—focusing on the latest testing lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic that identifies patients with high-risk lymphoid malignancies or plasma cell dyscrasias, which require more aggresive treatment leukemia, multiple myeloma and • Novel targeted therapies or intensified regimens based on the other plasma cell disorders. cancer’s genetic and molecular profile • Transplant & Cellular Therapy program ranked among the top 10% nationally in patient outcomes for allogeneic transplant • Clinical trials that offer tomorrow’s treatments today www.roswellpark.org/partners-in-practice Partners In Practice medical information for physicians by physicians We want to give every patient their very best chance for cure, and that means choosing Roswell Park Pathology—Taking the best and Diagnosis to a New Level “ optimal front-line Lymphoma and myeloma are a diverse and heterogeneous group of treatment.” malignancies. Lymphoid malignancy classification currently includes nearly 60 different variants, each with distinct pathophysiology, clinical behavior, response to treatment and prognosis. Our diagnostic approach in hematopathology includes the comprehensive examination of lymph node, bone marrow, blood and other extranodal and extramedullary tissue samples, and integrates clinical and diagnostic information, using a complex array of diagnostics from the following support laboratories: • Bone marrow laboratory — Francisco J. -

Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma / Lymphomatoid

Primary Cutaneous CD30-Positive T-cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders Definition A spectrum of related conditions originating from transformed or activated CD30-positive T-lymphocytes May coexist in individual patients Clonally related Overlapping clinical and/or histological features Clinical, histologic, and phenotypic characteristics required for diagnosis Types 1. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (C-ALCL) 2. Lymphomatoid papulosis 3. Borderline lesions C-ALCL: Definition T-cell lymphoma, presenting in the skin and consisting of anaplastic lymphoid cells, the majority of which are CD30- positive Distinction from: (a) systemic ALCL with cutaneous involvement, and (b) secondary high-grade lymphomas with CD30 expression In nearly all patients disease is limited to the skin at the time of diagnosis Assessed by meticulous staging Patients should not have other subtypes of lymphoma C-ALCL: Synonyms Lukes-Collins: Not listed (T-immunoblastic) Kiel: Anaplastic large cell Working Formulation: Various categories (diffuse large cell; immunoblastic) REAL: Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell (CD30+) lymphoma Related terms: Regressing atypical histiocytosis; Ki-1 lymphoma C-ALCL: Epidemiology 25% of the T-cell lymphomas arising primarily in the skin. Predominantly in adults/elderly and rare in children. The male to female ratio is 1.5-2.0:1. C-ALCL: Sites of Involvement The disease is nearly always limited to the skin at the time of diagnosis Extracutaneous dissemination may occur Mainly regional lymph nodes Involvement of other organs is rare C-ALCL: Clinical Features Most present solitary or localized skin lesions which may be tumors, nodules or (more rarely) papules Multicentric cutaneous disease occurs in 20% Lesions may show partial or complete spontaneous regression (similar to lymphomatoid papulosis) Cutaneous relapses are frequent Extracutaneous dissemination occurs in approximately 10% of the patients. -

Low-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Book

Low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma Low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma Follicular lymphoma Mantle cell lymphoma Marginal zone lymphomas Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia This book has been researched and written for you by Lymphoma Action, the only UK charity dedicated to people affected by lymphoma. We could not continue to support you, your clinical team and the wider lymphoma community, without the generous donations of our incredible supporters. As an organisation we do not receive any government or NHS funding and so every penny received is truly valued. To make a donation towards our work, please visit lymphoma-action.org.uk/Donate 2 Your lymphoma type and stage Your treatment Key contact Name: Role: Contact details: Job title/role Name and contact details GP Consultant haematologist/ oncologist Clinical nurse specialist or key worker Treatment centre 3 About this book Low-grade (or indolent) non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a type of blood cancer that develops from white blood cells called lymphocytes. It is a broad term that includes lots of different types of lymphoma. This book explains what low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma is and how it is diagnosed and treated. It includes tips on coping with treatment and dealing with day-to-day life. The book is split into chapters. You can dip in and out of it and read the sections that are relevant to you at any given time. Important and summary points are written in the chapter colour. Lists practical tips and chapter summaries. Gives space for questions and notes. Lists other resources you might find useful, some of which are online. -

Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma in the Era of New Drugs and CAR-T Cell Therapy

cancers Review Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma in the Era of New Drugs and CAR-T Cell Therapy Miriam Marangon 1, Carlo Visco 2 , Anna Maria Barbui 3, Annalisa Chiappella 4, Alberto Fabbri 5, Simone Ferrero 6,7 , Sara Galimberti 8 , Stefano Luminari 9,10 , Gerardo Musuraca 11, Alessandro Re 12 , Vittorio Ruggero Zilioli 13 and Marco Ladetto 14,15,* 1 Department of Hematology, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano Isontina, 34129 Trieste, Italy; [email protected] 2 Section of Hematology, Department of Medicine, University of Verona, 37134 Verona, Italy; [email protected] 3 Hematology Unit, ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, 24127 Bergamo, Italy; [email protected] 4 Division of Hematology, Fondazione IRCCS, Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 5 Hematology Division, Department of Oncology, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Senese, 53100 Siena, Italy; [email protected] 6 Hematology Division, Department of Molecular Biotechnologies and Health Sciences, Università di Torino, 10126 Torino, Italy; [email protected] 7 Hematology 1, AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, 10126 Torino, Italy 8 Hematology Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Pisa, 56126 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] 9 Hematology Unit, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42123 Modena, Italy; [email protected] 10 Surgical, Medical and Dental Department of Morphological Sciences Related -

Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Coding Manual

Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Coding Manual Effective with Cases Diagnosed 1/1/2010 and Forward Published August 2021 Editors: Jennifer Ruhl, MSHCA, RHIT, CCS, CTR, NCI SEER Margaret (Peggy) Adamo, BS, AAS, RHIT, CTR, NCI SEER Lois Dickie, CTR, NCI SEER Serban Negoita, MD, PhD, CTR, NCI SEER Suggested citation: Ruhl J, Adamo M, Dickie L., Negoita, S. (August 2021). Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Coding Manual. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 2021. Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Coding Manual 1 In Appreciation NCI SEER gratefully acknowledges the dedicated work of Drs, Charles Platz and Graca Dores since the inception of the Hematopoietic project. They continue to provide support. We deeply appreciate their willingness to serve as advisors for the rules within this manual. The quality of this Hematopoietic project is directly related to their commitment. NCI SEER would also like to acknowledge the following individuals who provided input on the manual and/or the database. Their contributions are greatly appreciated. • Carolyn Callaghan, CTR (SEER Seattle Registry) • Tiffany Janes, CTR (SEER Seattle Registry) We would also like to give a special thanks to the following individuals at Information Management Services, Inc. (IMS) who provide us with document support and web development. • Suzanne Adams, BS, CTR • Ginger Carter, BA • Sean Brennan, BS • Paul Stephenson, BS • Jacob Tomlinson, BS Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Coding Manual 2 Dedication The Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Coding Manual (Heme manual) and the companion Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasm Database (Heme DB) are dedicated to the hard-working cancer registrars across the world who meticulously identify, abstract, and code cancer data. -

The Lymphoma Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers

The Lymphoma Guide Information for Patients and Caregivers Ashton, lymphoma survivor This publication was supported by Revised 2016 Publication Update The Lymphoma Guide: Information for Patients and Caregivers The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society wants you to have the most up-to-date information about blood cancer treatment. See below for important new information that was not available at the time this publication was printed. In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved obinutuzumab (Gazyva®) in combination with chemotherapy, followed by Gazyva alone in those who responded, for people with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma (stage II bulky, III or IV). In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris®) for treatment of adult patients with primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pcALCL) or CD30- expressing mycosis fungoides (MF) who have received prior systemic therapy. In October 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved acalabrutinib (CalquenceTM) for the treatment of adults with mantle cell lymphoma who have received at least one prior therapy. In October 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma. Yescarta is a CD19-directed genetically modified autologous T cell immunotherapy FDA approved. Yescarta is not indicated for the treatment of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. In September 2017, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved copanlisib (AliqopaTM) for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least two prior systemic therapies. -

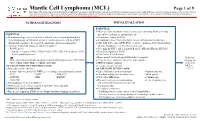

Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL)

Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) Page 1 of 9 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. PATHOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS INITIAL EVALUATION ESSENTIAL: ● Physical exam: attention to node-bearing areas, including Waldeyer's ring, ESSENTIAL: size of liver and spleen, and patient’s age ● Hematopathology review of all slides with at least one tumor paraffin block. ● Performance status (ECOG) Hematopathology confirmation of classic versus aggressive variant of MCL ● B symptoms (fever, drenching night sweats, unintentional weight loss) (blastoid/pleomorphic). Re-biopsy if consult material is non-diagnostic. ● CBC with differential, LDH, BUN, creatinine, albumin, AST, total bilirubin, 1 ● Adequate immunophenotype to confirm diagnosis alkaline phosphatase, serum calcium, uric acid ○ Paraffin panel: ● Screening for HIV 1 and 2, hepatitis B and C (HBcAb, HBaAg, HCVAb) - Pan B-cell marker (CD19, CD20, PAX5), CD3, CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1 ● Beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) - Ki-67 (proliferation rate) ● Chest x-ray, PA and lateral or ● Bone marrow bilateral biopsy with unilateral aspirate Induction ○ Flow cytometry immunophenotyping: -

Divergent Clonal Evolution of a Common Precursor to Mantle Cell Lymphoma and Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma

Downloaded from molecularcasestudies.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Divergent clonal evolution of a common precursor to mantle cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma Hammad Tashkandi1, Kseniya Petrova-Drus1, Connie Lee Batlevi2, Maria Arcila1, Mikhail Roshal1, Filiz Sen1, Jinjuan Yao1, Jeeyeon Baik1, Ashley Bilger2, Jessica Singh2, Stephanie de Frank2, Anita Kumar2, Ruth Aryeequaye1, Yanming Zhang1, Ahmet Dogan1, Wenbin Xiao1,* 1Department of Pathology, 2Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY *Correspondence: Wenbin Xiao, MD, PhD Department of Pathology Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center 1275 York Avenue New York, NY 10065 [email protected] Running title: Clonally related mantle cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma Words: 1771 Figures: 2 Tables: 1 Reference: 14 Supplemental materials: Figure S1-S2, Table S1-S4 Downloaded from molecularcasestudies.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Abstract: Clonal heterogeneity and evolution of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) remain unclear despite the progress in our understanding of its biology. Here we report a 71 years old male patient with an aggressive MCL and depict the clonal evolution from initial diagnosis of typical MCL to relapsed blastoid MCL. During the course of disease, the patient was diagnosed with Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), and received CHL therapeutic regimen. Molecular analysis by next generation sequencing of both MCL and CHL demonstrated clonally related CHL with characteristic immunophenotype and PDL1/2 gains. Moreover, our data illustrate the clonal heterogeneity and acquisition of additional genetic aberrations including a rare fusion of SEC22B-NOTCH2 in the process of clonal evolution. -

Indolent Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas

Follicular and Low-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (Indolent Lymphomas) Stefan K Barta, M.D., M.S. Associate Professor of Medicine Leader, T Cell Lymphoma Program Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine Facts and Figures: Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas • Most common blood cancer • 7th most common cancer in the US3 • 71,850 new cases in the US in 20151 • 19,790 died of NHL in 20151 • About 549,625 people are living with a history of NHL (2012)1 • 85% of all NHLs are B-cell lymphomas2 • Follicular lymphoma = 2nd most common type, ~25% of all NHLs4 1 http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/nhl.html. 2 ACS. Detailed Guide (revised January 21, 2000): Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. 3 http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/commoncancers 4 Blood 89: 3909, 1997 The Immune System T- CELLS B- CELLS Cellular immunity: Humoral immunity: helper + cytotoxic T-cells antibodies Lymphatic System Lymph Node Anatomy Lymph Node: Microscopic View germinal center Lymphocyte: Microscopic View Causes Possible cause(s): • chemical exposures (pesticides, fertilizers or solvents) • individuals with compromised immune systems • heredity • infections (e.g. H. pylori, Hep C, chlamydia trachomatis) • most patients have no clear risk factors • IN MOST CASES, THE EXACT CAUSE IS UNKNOWN Cellular Origins of Lymphomas & Leukemias PLEURIPOTENT STEM CELL ACUTE LEUKEMIAS LYMPHOID STEM CELL ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKEMIAS PRECURSOR T - CELL PRECURSOR B - CELL LYMPHOBLASTIC LYMPHOMAS / LEUKEMIAS MATURE T - CELL MATURE B - CELL NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMAS / CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA LYMPH NODES, EXTRANODAL -

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphoproliferative disorders Objectives: • To understand the general features of lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) • To understand some benign causes of LPD such as infectious mononucleosis • To understand the general classification of malignant LPD Important. • To understand the clinicopathological features of chronic lymphoid leukemia Extra. • To understand the general features of the most common Notes (LPD) (Burkitt lymphoma, Follicular • lymphoma, multiple myeloma and Hodgkin lymphoma). Success is the result of perfection, hard work, learning Powellfrom failure, loyalty, and persistence. Colin References: Editing file 435 teamwork slides 6 girls & boys slides Do you have any suggestions? Please contact us! @haematology436 E-mail: [email protected] or simply use this form Definitions Lymphoma (20min) Lymphoproliferative disorders: Several clinical conditions in which lymphocytes are produced in excessive quantities (Lymphocytosis) increase in lymphocytes that are not normal Lymphoma: Malignant lymphoid mass involving the lymphoid tissues. (± other tissues e.g: skin, GIT, CNS ..) The main deference between Lymphoma & Leukemia is that the Lymphoma proliferate primarily in Lymphoid Tissue and cause Mass , While Leukemia proliferate mainly in BM& Peripheral blood Lymphoid leukemia: Malignant proliferation of lymphoid cells in Bone marrow and peripheral blood. (± other tissues e.g: lymph nodes, spleen, skin, GIT, CNS ..) BCL is an anti-apoptotic (prevent apoptosis) Lymphocytosis (causes) 1- Viral infection: 2- Some* bacterial