Mississippi Sports Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2021 NCAA WOMEN's BASKETBALL GAME ADMINISTRATION and TABLE CREW REFERENCE SHEET GAME ADMINISTRATION Game Administration

2019-2021 NCAA WOMEN’S BASKETBALL GAME ADMINISTRATION AND TABLE CREW REFERENCE SHEET Edited by Jon M. Levinson, Women’s Basketball Secretary-Rules Editor [email protected] GAME ADMINISTRATION Game administration shall make available an individual at each basket with a device capable of untangling the net when necessary. The individual must ensure that play has clearly moved away from the affected basket before going onto the playing court. SCORER It is strongly recommended that the scorer be present at the table with no less than 15 minutes remaining on the pregame clock. Signals 1. For a team’s fifth foul, the scorer will display two fingers and verbally state the team is in the bonus. The public- address announcer is not to announce the number of team fouls beyond the fifth team foul. 2. in a game with replay equipment, record the time on the game clock when the official signals for reviewing a two- or three-point goal. 3. For a disqualified player, the scorer will inform the officials as soon as possible by displaying five fingers with an open hand and verbally state that this is the fifth foul on the number of the disqualified player. New Rules 1. During two- or three-shot free throw situations, substitutes are permitted before the first attempt or when the last attempt is successful. 2. A replaced player may reenter the game before the game clock has properly started and stopped when the opposing team has committed a foul or violation. GAME CLOCK TIMER TIMER must: 1. Confirm with the officials that the game clock is operating properly, which includes displaying tenths-of-a-second under one minute, the horn is operating, and the red/LED lights are functioning. -

Game Information

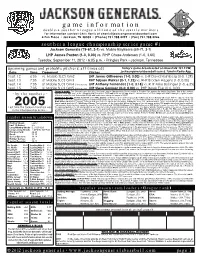

game information double-a southern league affiliate of the seattle mariners For Information contact Chris Harris at [email protected] 4 Fun Place • Jackson, TN 38305 • (Phone) 731.988.5299 • (Fax) 731.988.5246 southern league championship series game #1 Jackson Generals (79-61, 3-1) vs. Mobile BayBears (69-71, 3-1) LHP James Paxton (1-0, 0.00) vs. RHP Chase Anderson (1-0, 3.60) Tuesday, September 11, 2012 • 6:05 p.m. • Pringles Park • Jackson, Tennessee upcoming games and probable pitchers: all times cdt Today’s game broadcasted on NewsTalk 101.5 FM, Date Time Opponent Pitcher jacksongeneralsbaseball.com & TuneIn Radio App. Sept. 12 6:05 vs. Mobile SLCS Gm2 LHP James Gillheeney (1-0, 3.00) vs. LHP David Holmberg (0-0, 1.29) Sept. 13 7:05 at Mobile SLCS Gm3 RHP Taijuan Walker (0-1, 1.23) vs. RHP Braden Hagens (1-0, 0.00) Sept. 14 7:05 at Mobile SLCS Gm4 (if necessary) LHP Anthony Fernandez (1-0, 3.18) vs. RHP Mike Bolsinger (1-0, 6.35) Sept. 15 7:05 at Mobile SLCS Gm5 (if necessary) LHP Steve Garrison (0-0, 0.00) vs. RHP Derek Eitel (0-0, 0.00) TODAY’S GAME: The Generals open the 2012 Southern League Championship Series tonight at Pringles Park against the Mobile BayBears. This is the Jackson franchise’s first apperance in the Championship Series since 2005 and fourth overall appearance. Jackson won 6 of 10 meetings with Mobile during the regular season. - by the numbers - Mobile is looking for their 2nd straight SL title and fourth since joining the league in 19997. -

Arizona Diamondbacks 2015 Spring Training Game Notes

ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS 2015 SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES dbacks.com losdbacks.com @Dbacks @LosDbacks facebook.com/D-backs Salt River Fields at Talking Stick 7555 N. Pima Road, Scottsdale, Ariz., 85258 ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS (2-1) @ SEATTLE MARINERS (2-1) PRESS.DBACKSMEDIA.COM Saturday, March 7, 2015 ♦ Peoria Sports Complex ♦ Peoria, Ariz. ♦ 1:05 p.m. ♦Daily content includes media guides, game notes, statistical reports, lineups, Game No. 4 ♦ Road Game No. 2 ♦ Home Record: 1-1 ♦ Road Record: 1-0 press releases, etc.…please contact a D-backs’ Communications staff mem- RHP Josh Collmenter (NR) vs. RHP Hisashi Iwakuma (NR) ber for the login/password. Arizona Sports 98.7 FM 2015 D-BACKS SPRING SCHEDULE (2-1) DIAMOND-FACTS D-BACKS WEARING “KAYLA” PATCH THIS WEEK WINNING LOSING DATE OPP RESULT REC. PITCHER PITCHER ATT. ♦Arizona is in its 18th Cactus League season (fi fth in ♦D-backs are wearing a black patch with “KAYLA” 3/3 Arizona State W, 4-0 - Schugel Graybill 6,655 the Valley)…Tucson served as the club’s headquar- written on the sleeve in memory of Prescott resi- 3/4 @ COL W, 6-2 1-0 Blair (R, 1-0) Laffey (R, 0-1) 6,780 ters from 1998-2010. dent Kayla Mueller, a human rights activist who 3/5 COL W, 4-3 2-0 Nuño (R, 1-0) Butler (R, 0-1) 7,595 ♦D-backs are 2-1 this spring and 284-267-17 all-time passed away last month while being held captive by 3/6 OAK L, 2-7 2-1 Graveman (1-0) Ray (0-1) 10,726 in spring…in 2014, the D-backs went 12-13-3. -

The Astros' Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal Major League Baseball (MLB) fosters an extremely competitive environment. Tens of millions of dollars in salary (and endorsements) can hang in the balance, depending on whether a player performs well or poorly. Likewise, hundreds of millions of dollars of value are at stake for the owners as teams vie for World Series glory. Plus, fans, players and owners just want their team to win. And everyone hates to lose! It is no surprise, then, that the history of big-time baseball is dotted with cheating scandals ranging from the Black Sox scandal of 1919 (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”), to Gaylord Perry’s spitter, to the corked bats of Albert Belle and Sammy Sosa, to the widespread use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, the Houston Astros have joined this inglorious list. Catchers signal to pitchers which type of pitch to throw, typically by holding down a certain number of fingers on their non-gloved hand between their legs as they crouch behind the plate. It is typically not as simple as just one finger for a fastball and two for a curve, but not a lot more complicated than that. In September 2016, an Astros intern named Derek Vigoa gave a PowerPoint presentation to general manager Jeff Luhnow that featured an Excel-based application that was programmed with an algorithm. The algorithm was designed to (and could) decode the pitching signs that opposing teams’ catchers flashed to their pitchers. The Astros called it “Codebreaker.” One Astros employee referred to the sign- stealing system that evolved as the “dark arts.”1 MLB rules allowed a runner standing on second base to steal signs and relay them to the batter, but the MLB rules strictly forbade using electronic means to decipher signs. -

Time to Drop the Infield Fly Rule and End a Common Law Anomaly

A STEP ASIDE TIME TO DROP THE INFIELD FLY RULE AND END A COMMON LAW ANOMALY ANDREW J. GUILFORD & JOEL MALLORD† I1 begin2 with a hypothetical.3 It’s4 the seventh game of the World Series at Wrigley Field, Mariners vs. Cubs.5 The Mariners lead one to zero in the bottom of the ninth, but the Cubs are threatening with no outs and the bases loaded. From the hopeful Chicago crowd there rises a lusty yell,6 for the team’s star batter is advancing to the bat. The pitcher throws a nasty † Andrew J. Guilford is a United States District Judge. Joel Mallord is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School and a law clerk to Judge Guilford. Both are Dodgers fans. The authors thank their friends and colleagues who provided valuable feedback on this piece, as well as the editors of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review for their diligent work in editing it. 1 “I is for Me, Not a hard-hitting man, But an outstanding all-time Incurable fan.” OGDEN NASH, Line-Up for Yesterday: An ABC of Baseball Immortals, reprinted in VERSUS 67, 68 (1949). Here, actually, we. See supra note †. 2 Baseball games begin with a ceremonial first pitch, often resulting in embarrassment for the honored guest. See, e.g., Andy Nesbitt, UPDATE: 50 Cent Fires back at Ridicule over His “Worst” Pitch, FOX SPORTS, http://www.foxsports.com/buzzer/story/50-cent-worst-first-pitch-new-york- mets-game-052714 [http://perma.cc/F6M3-88TY] (showing 50 Cent’s wildly inaccurate pitch and his response on Instagram, “I’m a hustler not a damn ball player. -

A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions

Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 1995 A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions Joseph J. McMahon Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph J. McMahon Jr., A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions, 2 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 213 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McMahon: A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF BASEBALL'S THREE ANTITRUST EXEMPTIONS JOSEPH J. MCMAHON, JR.* AND JOHN P. RossI** I. INTRODUCTION What is professional baseball? It is difficult to answer this ques- tion without using a value-laden term which, in effect, tells us more about the speaker than about the subject. Professional baseball may be described as a "sport,"' our "national pastime,"2 or a "busi- ness."3 Use of these descriptors reveals the speaker's judgment as to the relative importance of professional baseball to American soci- ety. Indeed, all of the aforementioned terms are partially accurate descriptors of professional baseball. When a Scranton/Wilkes- Barre Red Barons fan is at Lackawanna County Stadium 4 ap- plauding a home run by Gene Schall, 5 the fan is engrossed in the game's details. -

2014 Starting Pitchers Fatigue Ratings GS BF BF

2014 Starting Pitchers Fatigue Ratings GS BF BF RATING Chase Anderson ARI 21 486 23 Bronson Arroyo ARI 14 357 26 Mike Bolsinger ARI 9 221 25 Trevor Cahill ARI 17 397 23 Andrew Chafin* ARI 3 60 20 Josh Collmenter ARI 28 683 24 Randall Delgado ARI 4 78 20 Wade Miley* ARI 33 866 26 Zeke Spruill ARI 1 29 29 Gavin Floyd ATL 9 229 25 David Hale ATL 6 138 23 Aaron Harang ATL 33 876 27 Mike Minor* ATL 25 637 25 Ervin Santana ATL 31 817 26 Julio Teheran ATL 33 884 27 Alex Wood* ATL 24 625 26 Wei-Yin Chen* BAL 31 772 25 Kevin Gausman BAL 20 476 24 Miguel Gonzalez BAL 26 662 25 Ubaldo Jimenez BAL 22 527 24 T.J. McFarland* BAL 1 20 20 Bud Norris BAL 28 687 25 Chris Tillman BAL 34 871 26 Clay Buchholz BOS 28 737 26 Rubby De La Rosa BOS 18 434 24 Anthony Ranaudo BOS 7 170 24 Allen Webster BOS 11 259 24 Brandon Workman BOS 15 353 24 Steven Wright BOS 1 22 22 Jake Arrieta CHC 25 614 25 Dallas Beeler CHC 2 46 23 Kyle Hendricks CHC 13 321 25 Edwin Jackson CHC 27 629 23 Eric Jokisch* CHC 1 20 20 Carlos Villanueva CHC 5 106 21 Tsuyoshi Wada* CHC 13 289 22 Travis Wood* CHC 31 781 25 Chris Bassitt CHW 5 137 27 Scott Carroll CHW 19 482 25 John Danks* CHW 32 855 27 Erik Johnson CHW 5 109 22 Charles Leesman* CHW 1 17 17 Felipe Paulino CHW 4 103 26 Jose Quintana* CHW 32 830 26 2014 Starting Pitchers Fatigue Ratings GS BF BF RATING Andre Rienzo CHW 11 262 24 Chris Sale* CHW 26 685 26 Dylan Axelrod CIN 4 69 17 Homer Bailey CIN 23 604 26 Tony Cingrani* CIN 11 262 24 Daniel Corcino CIN 3 66 22 Johnny Cueto CIN 34 961 28 David Holmberg* CIN 5 110 22 Mat Latos CIN 16 420 26 Mike Leake CIN 33 902 27 Alfredo Simon CIN 32 818 26 Trevor Bauer CLE 26 663 26 Carlos Carrasco CLE 14 360 26 T.J. -

November 2015 John M

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Latino Baseball History Project Newsletter John M. Pfau Library 11-2015 November 2015 John M. Pfau Library Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/lbhp Part of the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation John M. Pfau Library, "November 2015" (2015). Latino Baseball History Project Newsletter. Paper 11. http://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/lbhp/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latino Baseball History Project Newsletter by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOV. 2015 VOLUME 5 / ISSUE 1 LATINO BASEBALL HISTORY PROJECT: N E W S L E T T E R THE LATINO BASEBALL HISTORY PROJECT ANNOUNCES THE RELEASE OF ITS 7TH BOOK: MEXICAN AMERICAN BASEBALL IN THE SAN FERNANDO VALLEY The Latino Baseball History Project ringing their cars around the fi eld of play to form a makeshift is proud to announce the release outfi eld barrier or packed the grandstands of professional of its seventh book, Mexican quality baseball fi elds. Furthermore, Mexican Americans American Baseball in the San played alongside white, black and Japanese Americans. Fernando Valley on Oct. 19, 2015. The San Fernando Extensive travel to central California and into Mexico allowed Valley is located north of players to network with other regions. Games between the Los Angeles Basin, San Fernando Valley and visiting Mexican teams acted surrounded by the Santa as important diplomatic events, at times bringing together Susana, Santa Monica, San politicians such as the Los Angeles Mexican consul and Gabriel, and Verdugo California governor. -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! September 24 - 30, 2020 INSIDE: has a new home at The latest House & Home THE LINKS! Listings Chris Rock gets 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 Page 21 Jacksonville Beach dramatic as Offering: · Hydrafacials ‘Fargo’ returns · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring Chris Rock stars in the Season 4 premiere · B12 Complex / of “Fargo” Sunday on FX. Lipolean Injections Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 www.SkinnyJax.com1 x 5” ad Now is a great time to It will provide your home: List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while the home is listed • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a Broker Associate home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with [email protected] ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan America’s Preferred Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! Home Warranty for your home when we put it on the market. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN FX brings Chris Rock to ‘Fargo’ for series’ fourth season What’s Available NOW Though the last visit to “Fargo” was a and pitched him what I wanted to do, and while ago, it’s still on the television map. -

Houston Rockets General Manager's Tweet Sparks Controversy

Houston Rockets General Manager's tweet sparks controversy 08 OCTOBER 2019 Michael A. Rueda PARTNER | HEAD OF US SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT | US CATEGORY: BLOG CLIENT TYPES: FAMILY TALENT AND CREATIVES SPORT On October 4th, 2019, during a National Basketball Association (“ NBA”) sponsored trip to China, Houston Rockets general manager, Daryl Morey, tweeted “ght for freedom, stand with Hong Kong.” The tweet has since been deleted, but not before sparking geopolitical controversy and outrage from the Chinese government, which demanded an apology, and announced Tuesday, October 8th that it had canceled the planned broadcast of two NBA exhibition games due to be played in the country. The NBA had Morey apologize and put out a statement characterizing his tweet as “regrettable” and clarifying that his support for Hong Kong protesters “does not represent the Rockets or the NBA.” However, the NBA’s attempt to quell the backlash in China prompted its own backlash from United States law makers, including Ted Cruz, Beto O’Rourke, and Julián Castro who were among those to denounce the NBA for giving in to Chinese condemnations. Now, the commissioner of the NBA, Adam Silver, has announced that the NBA “will not put itself in a position of regulating what players, employees, and team owners say or will not say on these issues,” and added: “It is inevitable that people around the world… will have different viewpoints over different issues. It is not the role of the NBA to adjudicate those differences.” Silver will travel to Shanghai on Wednesday, October 9th to meet with ofcials and some of the NBA’s business partners in hopes of nding some common ground. -

Ncaa Women's Basketball Playing Rules History

NCAA WOMEN’S BASKETBALL PLAYING RULES HISTORY Important Rules Changes (through 2017-18) 2 IMPORTANT RULES CHANGES FOR WOMEN’S BASKETBALL warned after third foul, sent to bench after fourth. Committee notes that some 1891-92 are using open-bottom baskets, and notes that officials must make certain the Basketball is invented by Dr. James Naismith, instructor at YMCA Training ball has passed through the basket. School in Springfield, Massachusetts, in December 1891. His 13 original rules and description of the game are published in January 1892 and read by Senda Berenson, physical education instructor at nearby Smith College. 1910-11 She immediately creates new rules for women to discourage roughness and Dribbling is eliminated. introduces basketball to Smith women. Peach baskets and the soccer ball are used, but she divides the court into three equal sections and requires players to stay in their section. Stealing the ball is prohibited, players may not 1913-14 hold the ball more than three seconds and there is a three-bounce limit on Single dribble returns, retaining requirement that ball must bounce knee- dribbles. Berenson’s rules, often modified, spread rapidly across the country high. If the court is small, the court can be divided in half and the center on via YMCAs and colleges, but many women also used men’s rules. five-player team (center had special markings) could play entire court but not shoot for a basket. 1894-95 Berenson’s article describing her game and its benefits in general terms is 1916-17 published in the September 1894 issue of the magazine Physical Edu cation. -

Introduction 1. Post Play 2.Screening – Legal/Illegal 3. Charging/ Blocking 4

FIBA Guidelines for Referee Education SCRIPT Points of Emphasis – Guidelines for Officiating INTRODUCTION 1. POST PLAY 2.SCREENING – LEGAL/ILLEGAL 3. CHARGING/ BLOCKING 4. REBOUNDS 5. UNSPORTSMANLIKE FOUL 6. ACT OF SHOOTING 7. FREE THROW VIOLATIONS 8. TRAVELLING 9. 24 SECONDS 10. GOAL TENDING & INTERFERENCE 11. TECHNICAL FOUL INTRODUCTION FIBA Logo & Title Points of Emphasis – Guidelines for Officiating Page 1 of 58 Montage of moments VOICE OVER (VO) from Athens Olympics, The Basketball tournament of Athens 2004 was one of the most including coaches brilliant events of the Olympic program. reactions, fans and major highlights. Generally the officiating of the games was of a high standard, contributing to the success of the tournament, with most situations well interpreted by all referees. However, there were a number of game situations and rulings that were reacted to with different perspectives and interpretations. This DVD is produced by FIBA to assist in focusing the spirit and intent of the rules as an aid to the training of all involved in basketball, including coaches, players and of course the referees. All references and examples where the calls were wrong or missed can’t be regarded as a personal criticism of any official. It must be understood that this is done for educational reasons only. 1. POST PLAY Montage of 3 point VO shots from Athens Modern Basketball has become more of a perimeter and outside Olympics & Post Play game due to the influence and value of the three point line and shot. However, strong and powerful pivot and post play remain an integral part of the game.