Entropy. Temperature. Chemical Potential. Thermodynamic Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Entropy, Information, and Conservation of Information

entropy Article On Entropy, Information, and Conservation of Information Yunus A. Çengel Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The term entropy is used in different meanings in different contexts, sometimes in contradic- tory ways, resulting in misunderstandings and confusion. The root cause of the problem is the close resemblance of the defining mathematical expressions of entropy in statistical thermodynamics and information in the communications field, also called entropy, differing only by a constant factor with the unit ‘J/K’ in thermodynamics and ‘bits’ in the information theory. The thermodynamic property entropy is closely associated with the physical quantities of thermal energy and temperature, while the entropy used in the communications field is a mathematical abstraction based on probabilities of messages. The terms information and entropy are often used interchangeably in several branches of sciences. This practice gives rise to the phrase conservation of entropy in the sense of conservation of information, which is in contradiction to the fundamental increase of entropy principle in thermody- namics as an expression of the second law. The aim of this paper is to clarify matters and eliminate confusion by putting things into their rightful places within their domains. The notion of conservation of information is also put into a proper perspective. Keywords: entropy; information; conservation of information; creation of information; destruction of information; Boltzmann relation Citation: Çengel, Y.A. On Entropy, 1. Introduction Information, and Conservation of One needs to be cautious when dealing with information since it is defined differently Information. Entropy 2021, 23, 779. -

Thermodynamics Notes

Thermodynamics Notes Steven K. Krueger Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Utah August 2020 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is thermodynamics? . .1 1.2 The atmosphere . .1 2 The Equation of State 1 2.1 State variables . .1 2.2 Charles' Law and absolute temperature . .2 2.3 Boyle's Law . .3 2.4 Equation of state of an ideal gas . .3 2.5 Mixtures of gases . .4 2.6 Ideal gas law: molecular viewpoint . .6 3 Conservation of Energy 8 3.1 Conservation of energy in mechanics . .8 3.2 Conservation of energy: A system of point masses . .8 3.3 Kinetic energy exchange in molecular collisions . .9 3.4 Working and Heating . .9 4 The Principles of Thermodynamics 11 4.1 Conservation of energy and the first law of thermodynamics . 11 4.1.1 Conservation of energy . 11 4.1.2 The first law of thermodynamics . 11 4.1.3 Work . 12 4.1.4 Energy transferred by heating . 13 4.2 Quantity of energy transferred by heating . 14 4.3 The first law of thermodynamics for an ideal gas . 15 4.4 Applications of the first law . 16 4.4.1 Isothermal process . 16 4.4.2 Isobaric process . 17 4.4.3 Isosteric process . 18 4.5 Adiabatic processes . 18 5 The Thermodynamics of Water Vapor and Moist Air 21 5.1 Thermal properties of water substance . 21 5.2 Equation of state of moist air . 21 5.3 Mixing ratio . 22 5.4 Moisture variables . 22 5.5 Changes of phase and latent heats . -

ENERGY, ENTROPY, and INFORMATION Jean Thoma June

ENERGY, ENTROPY, AND INFORMATION Jean Thoma June 1977 Research Memoranda are interim reports on research being conducted by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, and as such receive only limited scientific review. Views or opinions contained herein do not necessarily represent those of the Institute or of the National Member Organizations supporting the Institute. PREFACE This Research Memorandum contains the work done during the stay of Professor Dr.Sc. Jean Thoma, Zug, Switzerland, at IIASA in November 1976. It is based on extensive discussions with Professor HAfele and other members of the Energy Program. Al- though the content of this report is not yet very uniform because of the different starting points on the subject under consideration, its publication is considered a necessary step in fostering the related discussion at IIASA evolving around th.e problem of energy demand. ABSTRACT Thermodynamical considerations of energy and entropy are being pursued in order to arrive at a general starting point for relating entropy, negentropy, and information. Thus one hopes to ultimately arrive at a common denominator for quanti- ties of a more general nature, including economic parameters. The report closes with the description of various heating appli- cation.~and related efficiencies. Such considerations are important in order to understand in greater depth the nature and composition of energy demand. This may be highlighted by the observation that it is, of course, not the energy that is consumed or demanded for but the informa- tion that goes along with it. TABLE 'OF 'CONTENTS Introduction ..................................... 1 2 . Various Aspects of Entropy ........................2 2.1 i he no me no logical Entropy ........................ -

Practice Problems from Chapter 1-3 Problem 1 One Mole of a Monatomic Ideal Gas Goes Through a Quasistatic Three-Stage Cycle (1-2, 2-3, 3-1) Shown in V 3 the Figure

Practice Problems from Chapter 1-3 Problem 1 One mole of a monatomic ideal gas goes through a quasistatic three-stage cycle (1-2, 2-3, 3-1) shown in V 3 the Figure. T1 and T2 are given. V 2 2 (a) (10) Calculate the work done by the gas. Is it positive or negative? V 1 1 (b) (20) Using two methods (Sackur-Tetrode eq. and dQ/T), calculate the entropy change for each stage and ∆ for the whole cycle, Stotal. Did you get the expected ∆ result for Stotal? Explain. T1 T2 T (c) (5) What is the heat capacity (in units R) for each stage? Problem 1 (cont.) ∝ → (a) 1 – 2 V T P = const (isobaric process) δW 12=P ( V 2−V 1 )=R (T 2−T 1)>0 V = const (isochoric process) 2 – 3 δW 23 =0 V 1 V 1 dV V 1 T1 3 – 1 T = const (isothermal process) δW 31=∫ PdV =R T1 ∫ =R T 1 ln =R T1 ln ¿ 0 V V V 2 T 2 V 2 2 T1 T 2 T 2 δW total=δW 12+δW 31=R (T 2−T 1)+R T 1 ln =R T 1 −1−ln >0 T 2 [ T 1 T 1 ] Problem 1 (cont.) Sackur-Tetrode equation: V (b) 3 V 3 U S ( U ,V ,N )=R ln + R ln +kB ln f ( N ,m ) V2 2 N 2 N V f 3 T f V f 3 T f ΔS =R ln + R ln =R ln + ln V V 2 T V 2 T 1 1 i i ( i i ) 1 – 2 V ∝ T → P = const (isobaric process) T1 T2 T 5 T 2 ΔS12 = R ln 2 T 1 T T V = const (isochoric process) 3 1 3 2 2 – 3 ΔS 23 = R ln =− R ln 2 T 2 2 T 1 V 1 T 2 3 – 1 T = const (isothermal process) ΔS 31 =R ln =−R ln V 2 T 1 5 T 2 T 2 3 T 2 as it should be for a quasistatic cyclic process ΔS = R ln −R ln − R ln =0 cycle 2 T T 2 T (quasistatic – reversible), 1 1 1 because S is a state function. -

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

Entropy: Ideal Gas Processes

Chapter 19: The Kinec Theory of Gases Thermodynamics = macroscopic picture Gases micro -> macro picture One mole is the number of atoms in 12 g sample Avogadro’s Number of carbon-12 23 -1 C(12)—6 protrons, 6 neutrons and 6 electrons NA=6.02 x 10 mol 12 atomic units of mass assuming mP=mn Another way to do this is to know the mass of one molecule: then So the number of moles n is given by M n=N/N sample A N = N A mmole−mass € Ideal Gas Law Ideal Gases, Ideal Gas Law It was found experimentally that if 1 mole of any gas is placed in containers that have the same volume V and are kept at the same temperature T, approximately all have the same pressure p. The small differences in pressure disappear if lower gas densities are used. Further experiments showed that all low-density gases obey the equation pV = nRT. Here R = 8.31 K/mol ⋅ K and is known as the "gas constant." The equation itself is known as the "ideal gas law." The constant R can be expressed -23 as R = kNA . Here k is called the Boltzmann constant and is equal to 1.38 × 10 J/K. N If we substitute R as well as n = in the ideal gas law we get the equivalent form: NA pV = NkT. Here N is the number of molecules in the gas. The behavior of all real gases approaches that of an ideal gas at low enough densities. Low densitiens m= enumberans tha oft t hemoles gas molecul es are fa Nr e=nough number apa ofr tparticles that the y do not interact with one another, but only with the walls of the gas container. -

Einstein Solid 1 / 36 the Results 2

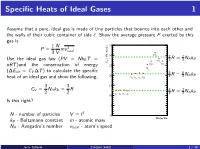

Specific Heats of Ideal Gases 1 Assume that a pure, ideal gas is made of tiny particles that bounce into each other and the walls of their cubic container of side `. Show the average pressure P exerted by this gas is 1 N 35 P = mv 2 3 V total SO 30 2 7 7 (J/K-mole) R = NAkB Use the ideal gas law (PV = NkB T = V 2 2 CO2 C H O CH nRT )and the conservation of energy 25 2 4 Cl2 (∆Eint = CV ∆T ) to calculate the specific 5 5 20 2 R = 2 NAkB heat of an ideal gas and show the following. H2 N2 O2 CO 3 3 15 CV = NAkB = R 3 3 R = NAkB 2 2 He Ar Ne Kr 2 2 10 Is this right? 5 3 N - number of particles V = ` 0 Molecule kB - Boltzmann constant m - atomic mass NA - Avogadro's number vtotal - atom's speed Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 1 / 36 The Results 2 1 N 2 2 N 7 P = mv = hEkini 2 NAkB 3 V total 3 V 35 30 SO2 3 (J/K-mole) V 5 CO2 C N k hEkini = NkB T H O CH 2 A B 2 25 2 4 Cl2 20 H N O CO 3 3 2 2 2 3 CV = NAkB = R 2 NAkB 2 2 15 He Ar Ne Kr 10 5 0 Molecule Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 2 / 36 Quantum mechanically 2 E qm = `(` + 1) ~ rot 2I where l is the angular momen- tum quantum number. -

Thermodynamics, Flame Temperature and Equilibrium

Thermodynamics, Flame Temperature and Equilibrium Combustion Summer School 2018 Prof. Dr.-Ing. Heinz Pitsch Course Overview Part I: Fundamentals and Laminar Flames • Introduction • Fundamentals and mass balances of combustion systems • Thermodynamic quantities • Thermodynamics, flame • Flame temperature at complete temperature, and equilibrium conversion • Governing equations • Chemical equilibrium • Laminar premixed flames: Kinematics and burning velocity • Laminar premixed flames: Flame structure • Laminar diffusion flames • FlameMaster flame calculator 2 Thermodynamic Quantities First law of thermodynamics - balance between different forms of energy • Change of specific internal energy: du specific work due to volumetric changes: δw = -pdv , v=1/ρ specific heat transfer from the surroundings: δq • Related quantities specific enthalpy (general definition): specific enthalpy for an ideal gas: • Energy balance for a closed system: 3 Multicomponent system • Specific internal energy and specific enthalpy of mixtures • Relation between internal energy and enthalpy of single species 4 Multicomponent system • Ideal gas u and h only function of temperature • If cpi is specific heat at constant pressure and hi,ref is reference enthalpy at reference temperature Tref , temperature dependence of partial specific enthalpy is given by • Reference temperature may be arbitrarily chosen, most frequently used: Tref = 0 K or Tref = 298.15 K 5 Multicomponent system • Partial molar enthalpy hi,m is and its temperature dependence is where the molar specific -

Statistical Physics Problem Sets 5–8: Statistical Mechanics

Statistical Physics xford hysics Second year physics course A. A. Schekochihin and A. Boothroyd (with thanks to S. J. Blundell) Problem Sets 5{8: Statistical Mechanics Hilary Term 2014 Some Useful Constants −23 −1 Boltzmann's constant kB 1:3807 × 10 JK −27 Proton rest mass mp 1:6726 × 10 kg 23 −1 Avogadro's number NA 6:022 × 10 mol Standard molar volume 22:414 × 10−3 m3 mol−1 Molar gas constant R 8:315 J mol−1 K−1 1 pascal (Pa) 1 N m−2 1 standard atmosphere 1:0132 × 105 Pa (N m−2) 1 bar (= 1000 mbar) 105 N m−2 Stefan{Boltzmann constant σ 5:67 × 10−8 Wm−2K−4 2 PROBLEM SET 5: Foundations of Statistical Mechanics If you want to try your hand at some practical calculations first, start with the Ideal Gas questions Maximum Entropy Inference 5.1 Factorials. a) Use your calculator to work out ln 15! Compare your answer with the simple version of Stirling's formula (ln N! ≈ N ln N − N). How big must N be for the simple version of Stirling's formula to be correct to within 2%? b∗) Derive Stirling's formula (you can look this up in a book). If you figure out this derivation, you will know how to calculate the next term in the approximation (after N ln N − N) and therefore how to estimate the precision of ln N! ≈ N ln N − N for any given N without calculating the factorials on a calculator. Check the result of (a) using this method. -

Particle Characterisation In

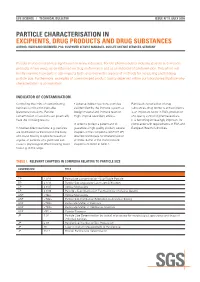

LIFE SCIENCE I TECHNICAL BULLETIN ISSUE N°11 /JULY 2008 PARTICLE CHARACTERISATION IN EXCIPIENTS, DRUG PRODUCTS AND DRUG SUBSTANCES AUTHOR: HILDEGARD BRÜMMER, PhD, CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER, SGS LIFE SCIENCE SERVICES, GERMANY Particle characterization has significance in many industries. For the pharmaceutical industry, particle size impacts products in two ways: as an influence on drug performance and as an indicator of contamination. This article will briefly examine how particle size impacts both, and review the arsenal of methods for measuring and tracking particle size. Furthermore, examples of compromised product quality observed within our laboratories illustrate why characterization is so important. INDICATOR OF CONTAMINATION Controlling the limits of contaminating • Adverse indirect reactions: particles Particle characterisation of drug particles is critical for injectable are identified by the immune system as substances, drug products and excipients (parenteral) solutions. Particle foreign material and immune reaction is an important factor in R&D, production contamination of solutions can potentially might impose secondary effects. and quality control of pharmaceuticals. have the following results: It is becoming increasingly important for In order to protect a patient and to compliance with requirements of FDA and • Adverse direct reactions: e.g. particles guarantee a high quality product, several European Health Authorities. are distributed via the blood in the body chapters in the compendia (USP, EP, JP) and cause toxicity to specific tissues or describe techniques for characterisation organs, or particles of a given size can of limits. Some of the most relevant cause a physiological effect blocking blood chapters are listed in Table 1. flow e.g. in the lungs. -

IB Questionbank

Topic 3 Past Paper [94 marks] This question is about thermal energy transfer. A hot piece of iron is placed into a container of cold water. After a time the iron and water reach thermal equilibrium. The heat capacity of the container is negligible. specific heat capacity. [2 marks] 1a. Define Markscheme the energy required to change the temperature (of a substance) by 1K/°C/unit degree; of mass 1 kg / per unit mass; [5 marks] 1b. The following data are available. Mass of water = 0.35 kg Mass of iron = 0.58 kg Specific heat capacity of water = 4200 J kg–1K–1 Initial temperature of water = 20°C Final temperature of water = 44°C Initial temperature of iron = 180°C (i) Determine the specific heat capacity of iron. (ii) Explain why the value calculated in (b)(i) is likely to be different from the accepted value. Markscheme (i) use of mcΔT; 0.58×c×[180-44]=0.35×4200×[44-20]; c=447Jkg-1K-1≈450Jkg-1K-1; (ii) energy would be given off to surroundings/environment / energy would be absorbed by container / energy would be given off through vaporization of water; hence final temperature would be less; hence measured value of (specific) heat capacity (of iron) would be higher; This question is in two parts. Part 1 is about ideal gases and specific heat capacity. Part 2 is about simple harmonic motion and waves. Part 1 Ideal gases and specific heat capacity State assumptions of the kinetic model of an ideal gas. [2 marks] 2a. two Markscheme point molecules / negligible volume; no forces between molecules except during contact; motion/distribution is random; elastic collisions / no energy lost; obey Newton’s laws of motion; collision in zero time; gravity is ignored; [4 marks] 2b.