Built Environment Auditing, Active Mobility and Children's Wellbeing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Índices De Caminhabilidade Urbana

ÍNDICES DE CAMINHABILIDADE URBANA Aplicação do projeto IAAPE ao planeamento urbano André Filipe Tomás Ferreira Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Civil Orientador: Prof. Doutor Filipe Manuel Mercier Vilaça e Moura Orientadora: Prof.a Ana dos Santos Morais de Sá Júri Presidente: Prof. Doutor João Torres de Quinhones Levy Orientadora: Prof.a Ana dos Santos Morais de Sá Vogal: Prof. Doutor Jorge Manuel Lopes Baptista e Silva Junho de 2017 ÍNDICES DE CAMINHABILIDADE URBANA: Aplicação do projeto IAAPE ao planeamento urbano 73260 – André Filipe Tomás Ferreira RESUMO E PALAVRAS-CHAVE O intenso processo de urbanização ocorrido nos últimos anos tem tido repercussões importantes no comportamento das pessoas, nomeadamente nas suas deslocações pedonais. Nos últimos anos o tema dos modos ativos de deslocação, em especial o modo pedonal, tem assumido um papel cada vez mais importante devido aos inúmeros benefícios que estes trazem para a saúde pública, para o ambiente, para a cidade, entre outros, tendo sido alvo de diversos estudos. Contudo a caminhabilidade tem sido essencialmente abordada no ambiente já construído, não havendo estudos realizados nos processos de planeamento urbano em relação a esta temática, em Portugal. Esta dissertação utiliza uma metodologia proposta pelo projeto IAAPE (Indicadores de Acessibilidade e Atratividade PEdonal) para realizar uma avaliação da caminhabilidade na Cidade Universitária, em Lisboa. Numa primeira fase avaliou-se a situação atual, a partir da qual foi possível concluir que a Cidade Universitária devido à sua especificidade de usos é acessível, mas pouco atrativa. Numa segunda fase, avaliaram-se as propostas incluídas no Plano de Pormenor para a Cidade Universitária (ainda em fase de elaboração) o que permitiu concluir que o Plano traria melhorias significativas na questão da caminhabilidade, em especial da atratividade da zona. -

An Audit of a Diverse Community for Safe Routes to Age in Place Environmental Policy Implications Adriana Perez, Phd, ANP-BC, FAAN; Anamarie Garces, MPH; Rebecca H

Public Policy An Audit of a Diverse Community for Safe Routes to Age in Place Environmental Policy Implications Adriana Perez, PhD, ANP-BC, FAAN; Anamarie Garces, MPH; Rebecca H. Hunter, MEd; and David X. Marquez, PhD ABSTRACT Physical and cognitive limitations of- ten accompany aging, increasing the importance of a safe and supportive environment to help older adults maintain mobility. Neighborhood design and maintenance must be evaluated to promote physical activ- ity, mobility, and safety. Audit tools, geographic information system data, and resident interviews are used for this purpose, but often fail to provide information that can be translated to practice. The current project is part of a larger Miami-Dade Age-Friendly Ini- tiative to create a metropolitan area that fosters a healthy environment for diverse adults of all ages and abili- ties. Safe Routes uses a toolkit based on the 5-E model providing practical © 2015 Shutterstock.com/kamira resources to guide stakeholders in ABOUT THE AUTHORS meeting the needs of the commu- Dr. Perez is Assistant Professor and Southwest Boarderlands Scholar, College of Nurs- nity. Findings include the Centers ing and Health Innovation, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona; Ms. Garces is Partner, Urban Health Solutions LLC, and Executive Director, Urban Health Partner- for Disease Control Healthy Aging ships, Inc., Miami, Florida; Dr. Hunter is Research Associate, University of North Carolina Research Network Audit Tool assess- Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; and Dr. Marquez is Associate Professor, Depart- ment for environmental walkability ment of Kinesiology and Nutrition, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. -

Main Street South Pedestrian Safety Study

MAIN STREET SOUTH PEDESTRIAN SAFETY STUDY SOUTHBURY, CONNECTICUT MAY 2020 MAIN STREET SOUTH PAGE | 1 PEDESTRIAN SAFETY STUDY This study is dedicated to the memory of DeLoris Curtis (1940 – 2020) “She took great pride in how Southbury got developed for future generations. She spent 40 years working for the Town of Southbury in various roles, most recently as the certified AICP planning administrator… The next time you take a walk down Main Street, look at the beautiful trees, flowers and sidewalk; think of her…” SOUTHBURY, CT MAY 2020 MAIN STREET SOUTH PAGE | 2 PEDESTRIAN SAFETY STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Study Purpose ………………………………………………………………...………... page 3 2. Background ..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 4 3. Existing Conditions …………………………………………………………….…………………………………. page 8 4. Recommended Improvements ………………………………………………………………...…………... page 16 5. Preliminary Cost-estimates ………………………………………………………………………...……….... page 36 6. Safety benefits of Recommended Improvements ………………………………………………... page 40 7. Next Steps ………………………………………………………………………...………………………………….. page 41 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…....…. page 43 SOUTHBURY, CT MAY 2020 MAIN STREET SOUTH PAGE | 3 PEDESTRIAN SAFETY STUDY 1. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY PURPOSE The Town of Southbury is seeking to improve pedestrian safety along Main Street South from Route 172 (South Britain Road & Georges Hill Road) to U.S. Route 6 (Main Street North). This approximately 1.8 mile stretch of Main Street South includes seven signalized intersections, many unsignalized intersections/driveways, a number of crosswalks (two at unsignalized locations), much of the town’s commercial base, some residential buildings, the Southbury Green, municipal/town government buildings and the Pomperaug Elementary School. The Rochambeau Middle School and adjacent neighborhoods are also in the vicinity of Main Street South. As the Town of Southbury seeks to improve the livability and safety of residents, employees, and visitors, it has undertaken this study with the aid of Milone & MacBroom, Inc. -

Pioneer Square Walking Audit

Pioneer Square Walking Audit DRAFTObservations & Recommendations April 20, 2012 Early one Tuesday morning in February, more than 40 people, representing residents, business, property owners and city departments, gathered in Occidental Park. Their goal: to understand what makes Pioneer Square a terrific place to be and to identify the opportunities for making it better. Their method: audit the streets and alleys of Pioneer Square. They set out on three different routes with a map, clipboard, a list of questions and a camera. They covered every corner of Pioneer Square, and they were prolific observers. These long-term residents and business owners created more than 40 pages of notes and took hundreds of photographs. Participants scored each route in three categories: getting there (finding your way and accessibility), wanting to stay (quality of public spaces and appearance) and feeling comfortable (quality of sidewalks and feeling of safety). Scores range from 1 representing poor to 5 being excellent. The result is an unprecedented inventory of Pioneer Square’s promises and challenges. The International Sustainability culled from this data what’s most important to those who work, live and play in Pioneer Square. You’ll find lots of quick wins and short term projects to support an economically vibrant neighborhood. If you have additional comments or ideas, please email [email protected]. project of PIONEER SQUARE ACTIVE STREETS prepared by the International Sustainability Institute 1.9 getting there 1.9 getting there SCORES 2.3 wanting to stay (1-5) Pioneer Square Walking Audit | ROUTE 1 | 2.5 feeling comfortable Transit & Neighborhood Connections: Occidental Park to Chinatown/ID and Transit Hub Uwajimaya 5th Ave ID 5 Assets & Promise Tunnel + Great Connection: between Chinatown/ID & Pioneer Square Union Station 4th Ave 4 Weller Bridge & 3 Sounder Entry + Transit Hub: brings people into Pioneer Square via numerous transit options (train, bus and light rail) 2 King St. -

Walking Audit Report

[This page was intentionally left blank.] Page 2 • City of Lauderhill Walking Audit Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Partners The Broward MPO would like to extend special thanks to the City of Lauderhill’s Commission and the School Administration at Lauderhill 6-12 STEM-MED Magnet Program. Dr. Reardon graciously allowed the event to be hosted within the school and the school administrators including Ms. Gina Montagnino and Leticia Mercado helped to organize the logistics and student-participation. City of Lauderhill Commissioner Thurston actively participated and Mayor Kaplan and Commissioner Bates attended the presentation, showing support for the Complete Streets-oriented workshop. The Broward MPO extend their gratitude to the more than 60 individuals who participated in the Walking Audit, and to the City of Lauderhill’s staff, both Earl Hahn and Molly Howson, for their assistance in preparing for the event. Roughly thirty students, from Lauderhill 6-12 provided the unique perspectives of young community members who use active transportation in the area almost every day, by walking to and from the school. Additional community support came from local agencies and nonprofit partners such as: Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT), Department of Health (FDOH) Broward Office, Broward Regional Health Planning Council’s (BRHPC) Transforming Our Community’s Health (TOUCH) Initiative partners, Broward Metropolitan Planning Organization (Broward MPO), AARP, Broward County Transit (BCT), and many others. The Broward MPO appreciates everyone’s participation -

Ja D C M B G Ill a Rs R

. e Dr . Park Ridg e Harrison D v r. A t M l u Morton Ave. l C lfo a r t d W . F . s y y e . Klos W . e Hill y e top Dr. W W v A d s Dr Stanton Ave. o la . n il o r i n l a l C w D z r e o n a ucero idg e C . A R M r v m D e u Mi . l ner o . Ave c B . l y. d u W R Joh ap r. e l n A c D id r. l ve. A la s w D a o e ie M an e v . p e H p Es r v t ro to T G i ll S l i Ga H rrity W ate lv y. h hg Dr. t g i . Hi e y 1 Pa w 1 bl w Pa o Vi H Pk lmer sta A ir. D ill Ave. ve. C r to d ew . p D on evi r. m at r. h G D Mckenz ic Co ller ie D R nnec Mi . r. ticu t y on Dr. t Ave. er Gilm Henders b W a D Ro r. a l A r. r airmede D l F E . t . t n r. a e e W D S e y. M v d . m M Wiswall D . r o h r u r A e ro ll . e i d t D n G s r b D 4 r a R Ri o B r. -

Practical Tools and Innovative Strategies for Creating Great Communities Speaker Biographies

14th Annual New Partners for Smart Growth: Practical Tools and Innovative Strategies for Creating Great Communities Speaker Biographies Azibuike Akaba Azibuike Akaba, Public Health Institute, is currently a policy Analyst that manages an environmental program that includes air quality; land use, transportation and public health policy. Currently he is a consultant for the AB32 Environmental Justice Advisory Board for the California Air Resources Board. Mustafa Ali Mustafa is a founding member of the Office of Environmental Justice (OEJ) and has a played major role in the design and implementation of many of EPA’s most successful programs focused on environmental justice and community revitalization. He currently serves as the Acting Senior Advisor to the Administrator for Environmental Justice. In this role Mustafa helps to elevate EJ issues to the highest levels of the Agency. Shirronda Almeida Shirronda Almeida, MACDC Director of Membership Initiatives, assists CDCs in improving their capacity as community resources through the Mel King Institute for Community Building. The Institute provides professional education and other learning opportunities for community development leadership, staff and board members. John Anderson John Anderson is a builder, developer, planner, and urbanist. Prior to the Great Recession he was the director of planning and design for New Urban Builders in Chico and Redding, where the firm has demonstrated that California production builders can build sustainable neighborhoods. In 2009 John and his partner David Kim formed Anderson / Kim Architecture + Urban Design with offices in Albuquerque and NYC. The firm specializes in infill design and development. Kate Ange Katharine Ange, AICP is a Principal and Vice President with Renaissance Planning Group. -

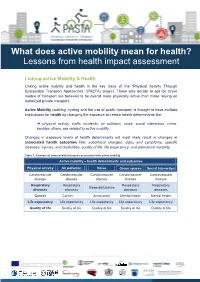

What Does Active Mobility Mean for Health? Lessons from Health Impact Assessment

What does active mobility mean for health? Lessons from health impact assessment Linking active Mobility & Health Linking active mobility and health is the key issue of the “Physical Activity Through Sustainable Transport Approaches” (PASTA) project. Those who decide to opt for active modes of transport are believed to be overall more physically active than those relying on motorized private transport. Active Mobility (walking, cycling and the use of public transport) is thought to have multiple implications for health by changing the exposure to certain health determinants like: physical activity, traffic incidents, air pollution, noise, social interaction, crime, besides others, are related to active mobility. Changes in exposure levels of health determinants will most likely result in changes in associated health outcomes like: subclinical changes, signs and symptoms, specific diseases, injuries, and disabilities, quality of life, life expectancy, and premature mortality. Table 1: Example of some health outcomes associated with active mobility Active mobility – health determinants and outcomes Physical activity Air pollution Noise Green spaces Social interaction Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular disease disease disease disease disease Respiratory Respiratory Respiratory Respiratory Sleep distubance diseases diseases diseases diseases Cancer Cancer Annoyance Mental health Mental health Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research; technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602624-2. Benefits one translates into benefits for all! The uptake of active mobility impacts not only the health determinants of individual travelers who decide to walk, cycle or use public transport, but also for society as a whole. -

Cycling to Work: Not Only a Utilitarian Movement but Also an Embodiment of Meanings and Experiences That Constitute Crucial

Conclusion This research analysed the different facets of utility cycling in Switzerland, using the example of commuting. We took as our starting point the concept of the cycling system, or velomobility, which underlines the importance of taking into account all elements—not only material and technical but also social, political and symbolic— which influence this practice. From this perspective, we argued that cycling—in terms of volume, frequency, distance, motivation, etc.—depends on the coming together of two potentials. The first of these is motility [11–13] or, more precisely, the indi- viduals’ cycling potential. It is built around access (‘to be able to’ use a means of transport), skills ((‘to know how to’ cycle for utility reasons) and appropriation (‘to want to’ cycle). Individuals’ appropriation of cycling depends on their perception of that mode and of its particularities, which can be interpreted as a confluence of three fundamental dimensions of mobility: movement, meaning and experience in a context of power in regards to the dominant system of automobility [6]. The second of the two potentials is the territory’s hosting potential, or its degree of bikeability, which relates to the spatial context, the available infrastructure and amenities (bicycle urbanism), as well as social and legal norms and rules. In order to identify a large sample of bicycle commuters, we focused on the bike to work scheme, which each year brings together people who commit to cycling to their place of work as often as possible during the months of May and/or June. Nearly 14,000 people completed an online questionnaire addressing the dimensions of velomobility. -

Safe Routes to School Bicycling and Walking Audit Report

Appendix O: Safe Routes to School Bicycling and Walking Audit Report City of Davis Draft Walk and Bike Audit Report November 2013 City of Davis Walk and Bike Audit Report Draft November 2013 Prepared for: City of Davis Prepared by: Alta Planning and Design In Partnership with: Parisi Transportation Consulting Acknowledgements Mayor and City Council Joe Krovoza, Mayor Dan Volk, Mayor Pro Tempore Lucas Frerichs, Councilmember Brett Lee, Councilmember Rochelle Swanson, Councilmember City Staff Bob Clarke, Public Works Director Brian Mickelson, Assistant City Engineer Roxanne Namazi, Senior Civil Engineer Rachel Hartsough, Project Manager, Street Smarts Program Manager David Kemp, Active Transportation Coordinator Alta Planning + Design Brett Hondorp, Principal Jennifer Donlon Wyant, Project Manager Christopher Kidd, Assistant Project Manager Parisi Transportation Consulting David Parisi, PE, TE This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... ES-1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1. What is Safe Routes to School? .......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.2. Project Goal............................................................................................................................................. 1-2 -

Existing Conditions June 2016 El Cajon Boulevard Table of Contents

ELSAN CAJONDIEGO BOULEVARD COMPLETE BOULEVARD PLANNING STUDY WORKING PAPER #1: EXISTING CONDITIONS JUNE 2016 EL CAJON BOULEVARD TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 | INTRODUCTION 1-1 6.2 | AREAS OF OPPORTUNITY 6-2 1.1 | PURPOSE OF STUDY 1-1 6.3 | LANDSCAPING 6-2 1.2 | STUDY CORRIDOR DESCRIPTION 1-1 6.4 | AREAS OF ENCROACHMENT 6-3 1.3 | REPORT ORGANIZATION 1-2 6.5 | STUDY CORRIDOR ENHANCEMENT OPPORTUNITIES 6-4 2 | PREVIOUS STUDY REVIEW 2-1 2.1 | CITY OF SAN DIEGO 2-1 2.2 | SANDAG 2-4 2.3 | METRO TRANSIT SYSTEM 2-5 2.4 | OTHER RELEVANT STUDIES 2-5 3 | AVAILABLE DATA 3-1 3.1 | AS-BUILT CADD DATA 3-1 3.2 | SANGIS 3-1 3.3 | INTERSECTION TRAFFIC CONTROL 3-5 3.4 | AREA CONNECTIONS 3-6 3.5 | PARKING AND TRUCK LOADING/UNLOADING 3-6 3.6 | SAFETY 3-8 4 | MULTIMODAL LEVEL OF SERVICE ANALYSIS 4-1 4.1 | LEVEL OF SERVICE ANALYSIS 4-1 4.2 | VEHICULAR 4-1 4.3 | TRANSIT 4-3 4.4 | PEDESTRIAN 4-5 4.5 | BICYCLE 4-10 5 | WALK AUDIT SUMMARY AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT 5-1 5.1 | WALK AUDIT SUMMARY 5-1 5.2 | FOCUS GROUP MEETING 5-3 5.3 | LITTLE SAIGON DISTRICT SURVEY 5-4 6 | ASSETS/LIABILITIES/OPPORTUNITIES/CONSTRAINTS 6-1 6.1 | OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS 6-1 i LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1-1 | El Cajon Boulevard Study Corridor 1-1 Figure 3-13 | Bike and Pedestrian Portion of Total Crashes 3-9 Figure 1-2 | Context of Study Area 1-1 Figure 3-14 | Crash Locations Involving Bicycle and Pedestrian (Years 2009-Oct.2013) 3-9 Figure 1-3 | Existing Conditions Photo Map 1-3 Figure 3-15 | Surrounding Area Bicycle and Pedestrian Involved Crash Locations 3-9 Figure 1-4 | Existing Conditions Photo -

Active Mobility in Singapore 19 Walking and Cycling in the Tropics

Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility 105 © 2014 Centre for Liveable Cities and Urban Land Institute. All rights reserved. Printed on Enviro Wove, an FSC Mix Credit Certified Paper ISBN 978-981-09-2479-9 (print) ISBN 978-981-09-2480-5 (e-book) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Every effort has been made to trace all sources and copyright holders of news articles, figures, and information in this book before publication. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, CLC and ULI will ensure that full credit is given at the earliest opportunity. The e-book can be accessed at http://clc.gov.sg/documents/books/active_ mobility/index.html 4 Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility 5 FOREWORD Cities are for people to live and enjoy. But A bolder plan is to support inter-town cycling. From the pressures on physical infrastructure of the Institute’s global networks to shape some cities are more liveable than others, This will be more challenging. Amsterdam such as transport, housing and public space projects and places in ways that improve the as a result of forward planning and sound took decades to wean off their attachment to through to intangible challenges such as health of people and communities. implementation. private cars and acquire a wonderful culture securing economic competitiveness and of walking and cycling.