NONCONFORMITY and the LABOUR MOVEMENT.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iris Murdoch

Sunday 9th August 2020 www.rmmc.org.uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/tempRMMC/ Last week I shared the first part of the story of Arthur & Ada Salter that had impressed me as I walked the Thames Path. Part Two included today with Part One as reference if you want to re-read! Zoom Church Service Aug 9, 2020 6pm led by Cathy Smith https://astrazeneca.zoom.us/j/99881042054?pwd=UWU3QmE0VkNYNXBMNENLd2dkVmh4QT09 Meeting ID: 998 8104 2054. Password: 562655 0203 481 5237 or 0800 260 5801 7.30pm Monday 10th August The Prayer Course Session 1: Why Pray? https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84151838035?pwd=WFpkZTBjUW9MSW9VL2VMRDBYcU9iUT09 ID: 841 5183 8035 Passcode: 483980. Landline: 0203 051 2874 ‘Prayer is simply paying attention to God, which is a form of love.’ Iris Murdoch Unlike the last course I am thinking of this one being once or twice a month, and with a different aspect of prayer each time it will be easy for people to attend as many sessions as they like and are able. I look for- ward to us learning together. Living Streets and Highways We pray for the living streets in our neighbourhood, where our daily travels begin and end, and our love of God inspires our interactions with our neighbours. In our walks and our rides and our drives and our deliveries, God keep us safe and looking out for others. Somebody during the post-service coffee session on last Sunday's zoom call asked for more de- tails about the Highway Code Consultation. In summary the proposed changes support a heirar- chy of road-users, prioritising people who are most vulnerable to harm, starting with pedestrians, (especially children, older adults and people with disabilities) and stating more clearly how all oth- er road users can reduce the danger they may pose to others. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

Red Flag Over Bermondsey - the Ada Salter Story

7.00 pm SATURDAY 5 DECEMBER 2015 RED FLAG OVER BERMONDSEY - THE ADA SALTER STORY Written and performed by Lynn Morris Directed by Dave Morris Where to start with Ada Salter? She was a true radical, campaigner for equal rights, socialist, republican, pacifist, environmentalist, trade union activist and a leading light in the transformation of the Bermondsey slums in the early part of the 20th century. Born into Methodism, she moved to London and became involved with the Bermondsey Settlement. She became a Quaker in 1914. She and her GP husband, Alfred Salter, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, living and working right in the heart of their community – and having to accept the tragic consequences of their choice. She and her husband were among the founders of the Independent Labour Party in Bermondsey. Ada herself broke through the glass ceiling of her time, becoming both the first woman councillor in London, and then the first woman mayor. Red Flag over Bermondsey explores the private and the public lives of Ada from 1909 until 1922, interwoven with her beloved Ira Sankey hymns and her passion for Handel. Further background about Ada (1866–1942) is to be found at www.quakersintheworld.org The performance lasts 65 minutes without interval. Lynn and Dave Morris are Journeymen theatre and they are committed to performing their work in any venue, theatre or non-theatre. Lynn and David attend Stourbridge Quaker Meeting. Visit the website at: www.journeymentheatre.com for details about the company, current and future productions, and reviews. Contact us at: [email protected] or [email protected] Admission FREE: All profits and donations from Red Flag over Bermondsey will be used to support our work with the Women’s Co-operative of Seir, West Bank, Palestine. -

New A4 Pages (Page 4)

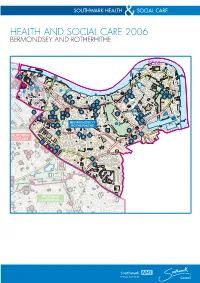

HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE GP Practices Southwark PCT Premises Pharmacies 1 The New Mill Street Surgery (Dr A Campion) 1 Mary Sheridan House 1 A.R. Chemists 1 Wolseley Street, SE1 2BP 11-19 Thomas Street, SE1 9RY 176-178 Old Kent Road, SE1 5TY Tel: 020 7252 1817 2 Mabel Goldwin House Tel: 020 7703 4097 2 Parkers Row Family Practice (Dr S Bhatti) 49 Grange Walk, SE1 3DY 2 ABC Pharmacy 2 Wade House, Parkers Row, SE1 2DN 3 Woodmill Building 243 Southwark Park Road, SE16 3TS Tel: 020 7237 1517 Neckinger, SE16 3QN Tel: 020 7237 1659 3 Alfred Salter Medical Centre (Dr S Bhatti) 4 Bermondsey Health Centre 3 Amadi Chemist 6-8 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW 107 Abbey Street, SE1 3NP Tel: 020 7237 1857 5 John Dixon Clinic Tel: 020 7771 3863 4 The Grange Road Practice (Dr M Brooks) Prestwood House, 4 Bonamy Pharmacy Bermondsey Health Centre, 201-209 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 355 Rotherhithe New Road, 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW Bonamy Estate, SE16 3HF Tel: 020 7237 1078 6 Albion Street Health Centre 87 Albion Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 7JX Tel: 020 7231 9988 5 Bemondsey and Lansdowne Medical Mission, 5 Boots The Chemist PLC (Dr R Torry) 7 St Olave's Nursing Home 15 Ann Moss Way, SE16 2TJ Unit 11-13 Surrey Quays Shopping Centre, Decima Street, SE1 4QX Redriff Road, SE16 9SP 8 Surrey Docks Health Centre Enquiries: 020 7407 0752 Tel: 020 7252 0084 Appointments: 020 7403 36186 Downtown Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 1NP 6 Boots The Chemist PLC 9 Silverlock Clinic 6 -

Alfred Salter Weekly

Alfred Salter Weekly st 21 May 2021 News from Alfred Salter Primary School Headteacher’s Message Alfred Salter’s Birthday It has been another busy week in school as We will be marking what would have been we near the end of this half term. I Alfred Salter’s birthday on Wednesday conducted a few more tours this week for 16th June 2021, which falls during D&T our new Reception parents and the feedback and week. The focus will be on the humanitarian work comments have been very positive. As these tours which he and his wife Ada Salter did for the have been very successful, we will be doing the community and the love they had for Bermondsey same after half term for our new Nursery families and Rotherhithe. We are hoping that the weather who will be joining the school in September. will be kind to us and that we can bring the whole I held several parental consultation meetings on the school together on the astroturf, in socially new statutory Relationships and Sex Education distanced bubbles, so that we can experience being (RSE) and health education curriculum on Thursday. together as a whole school after so long apart. We Thank you to all the parents and carers that will be sharing details shortly. attended. There were some really important queries Class Photos raised and questions asked. I hope that you found Braiswick, the school photographer will the meetings informative and any hesitations or be in on the morning of Monday 14th worries around RSE have been eased. -

Southwark Life

Southwark LifeWinter 2017 #TalkSouthwark Join the Conversation about our changing borough Festive Fun A look at what’s going on this Christmas Top of the Class Why Southwark’s schools are standing out Your magazine from Southwark Council Winter 2017 Contents 4 Need to know – All your Southwark news and festive information this winter welcome... 8 Southwark Conversation As 2017 draws to a close, it’s natural to look back over the year – Find out how to make your that’s passed. For Southwark, and London, 2017 was a year where voice heard as part of the we faced true tragedy on our doorsteps, with terrorist attacks in Southwark Conversation London Bridge and Borough, Westminster and beyond, as well as 10 Top of the class – Read why the awful fire at Grenfell Tower that claimed so many lives. We Southwark has some of the best learned a huge amount from these heartrending incidents, not schools in London least about how resilient we are as a borough and a city, pulling 12 Building a healthy together in the face of horror, offering our help and support to borough – What can we do to help people be healthier? strangers, refusing to give in to hate, but love instead. 15 Conversation – Our pull out Of course, we won’t ever forget those who lost their lives, or pages for you to complete and join in the conversation were hurt or scarred by these events, and we are working with Southwark Cathedral, Borough Market, the police, and anyone 20 Is Universal Credit else who wants to get involved on plans for a permanent memorial working? – We speak to people affected by the to those harmed on June 3rd. -

ROTHERHITHE 2) (B) Dockmasters Office and Clock Tower (1892) Mid C19 Steam Grain Mill and Warehouse

Sites of interest (numbered on map overleaf) 26) Old School House (1697) Est. 1613 for education of 8 sons of seamen by Peter Hills. Moved here 1795 1) (A) Deal Porters Statue, by Philip Bews Dockers carrying heavy timber across shoulders 27) Thames Tunnel Mills ROTHERHITHE 2) (B) Dockmasters Office and Clock Tower (1892) Mid C19 steam grain mill and warehouse. Site of steam ferry. Early residential conversion Rotherhithe, originally called Redriff from C13 and frequently 3) King George’s Field (public open space dedicated to King George V (1865-1936) 28)* (R) Mayflower Inn (1780) (formerly Spreadeagle) mentioned by the C17 diarist Samuel Pepys, came from the Site of All Saints Church. Destroyed during WWII List of passengers who sailed on the Mayflower. Licensed to sell US and UK stamps Anglo Saxon for a haven where cattle were landed. It was closely connected to Bermondsey Abbey, as well as having 4) Metropolitan drinking trough (from 1865) 29) (B) (D) Rotherhithe Picture Research Library & Sands Films Studios (Grice's Granary ancient river crossing points associated with shipbuilding and Fountains established by public subscription for humans, then troughs for horses and dogs, 1795) Library includes section on Rotherhithe. Film studio, production and costume making following C19 out breaks of cholera due to contaminated drinking water facilities. Houses one of London's smallest cinemas. www.sandsfilms.co.uk supporting trades (from C17 and probably from the middle ages), and seafaring is recorded in church memorials and 5) (B) Site of St. Olave's Hospital (1870-1985) 30)* (A) (B) (R) (D) Brunel Museum and Cafe (1842) gravestones. -

Transforming Education and Politics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Engendering city politics and educational thought: elite women and the London Labour Party, 1914-1965 Jane Martin Dr Jane Martin is Reader in History of Education at the Institute of Education, University of London. Her research interests are focused on the educational experiences of girls and women, women’s engagement in educational policy-making through participation in local and national politics, socialist politics around education, teachers and teaching, social identities and action, biographical theory and biographical method, historical theory and methodology, gender, education and empire. The author of Women and the Politics of Schooling in Victorian and Edwardian England (Leicester University Press, 1999) which won the History of Education Society Book Prize for 2002 and Women and Education 1800-1980 (Palgrave, 2004) with Joyce Goodman, she was the Brian Simon Educational Research Fellow 2004-05 nominated by the British Educational Research Association for her on-going biographical project on the British socialist educator activist Mary Bridges Adams (1855-1939). She is preparing a book length manuscript for Manchester University Press under the title: Making Socialists: Mary Bridges Adams and the Fight for Knowledge and Power. She is Editor of the journal History of Education. Address: Institute of Education, University of London, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H OAL 1 Abstract This article uses biographical approaches to recover the contribution of hitherto neglected figures in the history of education and the political history of the Left in London. Place and location are important since it is important to grasp the uniqueness of the London County Council within the framework of English local government and of the London Labour Party within the framework of the Labour Party. -

The Journal of the Women's History Network Spring 2017

Women’s History The journal of the Women’s History Network Spring 2017 Articles by Elizabeth A. O’Donnell, Peter Ayres, Eleanor Fitzsimons, Annemarie van Heerikhuizen, Irene Gill Plus Five book reviews Getting to know each other Committee News Volume 2 Issue 7 ISSN 2059-0164 www.womenshistorynetwork.org Women’s History Network Annual Conference, 2017 WOMEN AND THE WIDER WORLD Friday 1 September – Saturday 2 September 2017 University of Birmingham Image Credit: The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in Zurich, from LSE Library’s collections. Call for Papers We invite established scholars, postgraduate researchers, independent scholars, museum curators and practitioners from a wide range of disciplines, working on any place or period, to contribute to this year’s conference. Potential topics relating to ‘Women and the Wider World’ could include: Humanitarian activism, medieval warriors, the formation of professional identities in the international sphere, war work and philanthropy, mythological and folklore representations, migration, the Empire, suffrage through an international lens, travel writers and explorers, pilgrimages and religious travel, international diplomacy, anti-slavery campaigning, global artistic, literary, and intellectual networks, artistic and literary representations of women’s internationalism, pacifism and international peace movements, letter writing, international communities of educated women and women’s role in internationalising education, women on the crusades, the material culture and spaces of women’s internationalism, exchanges between women across colonial & Cold War borders, theorizing international feminism. We encourage those working in archaeology, museums studies, geography, history of science, technology and medicine, art history, environmental history and all forms of history for any period, focused on women, to send in proposals for themed 90 minute panels, individual 20 minute papers, 90-minute round tables/discussions, and posters. -

GIPE-003723-Contents.Pdf

DhananJayarao Gadgil ~ibrary 111111111111 0111 m~ lUll Mil 1m III GIPE-PWlE-003723 HandboOK~of ~ ~~,. -;" Local Government for England and Wales Ra. re -stcHur, Prepar~d for the use of Councillors + S:,~o~e:O~llG~~ ~"~i~"'~' ~ ftI PUBLISHED BY l'HJi: LABOUR PARTY, 33, ECCLESTON SQ., WESTMINSTER, S.W. I, t1 BY GEORGEi~ LEr{ ~ ITIiIW"- I~l~~~~m RUSKIN HOL_ f.J STREET, W.C. U,Sl\l I\.OU.)£ LIST OF. CONTRI'BUTORS R. PAGE ARNOT C. M. LLOYD MARGARET BURGE HERBERT MORRISON EMILE BURNS E. R. PEASE G. D. H. COLE MAIUOII PHILUI'S MARGARET I. COLI: RICHARD L. REISS EDWARD GILL ALFRED SALTER W. RSES JEFFREYS W. STEPHEN SANDn F. W. JOWETT W. H. THOMP'iON A. E. LAI"DER SIDNEY WEIS/I MABEL LAWRENCE .~~g S72~ This Handbook was prepared for the LABOUR- PARTY by The Advisory Committee on Local Government (Chairman, F. W. JowB'rT; Secretary, R. PAGB AIlNOT) €:I The Labour Research Department with the collaboration of The Fabian Society and The I.L.P. Information Committee CONTENTS I'AGI PREFACE-By F. W. JOWETT V PART I SCHEME OF LOCAL AUTJJORITIES 'PART 11 LOCAL, AUTHOIUTIES AND THEIR POWERS PART III PR.OCEDUR.E AND FINANCE PART IV HOUSING, TOWN PLANNING, EDUCATION, MILK SUPPLY, MATER. NITV AND CHILD WELFARE, FOOD CONTROL, PENSIONS, Pac>- FITEERll'IG PART V ALPHABET OF LOCAL SERVICES • 14'> BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE FIGHTING OF A MUNICIPAL ELECTION • • 193 DIRECTORY OF TRADES COUSCILS A~ DIVISIONAL AND LOCAL LAaouR PARTIES, - 203 PREFACE FTER the Labour victories in thE' Borough ~ouncils elections of Npvember, 1919. -

Pat Kingwell First Published 2010 Copyright Pat Kingwell the Friends of Southwark Park

OUR PARK Pat Kingwell First published 2010 Copyright Pat Kingwell The Friends of Southwark Park No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means without prior permission of the author. The Friends of Southwark Park Introduction enjoyable and fun way; In 1999 the Heritage Lottery to involve local people of all ages; to recount the Fund awarded Southwark history of Southwark Council a very large grant to Park, not only in the written word, but also carry out badly-needed through oral reminiscences, visual and aural restoration and improvement recordings, an exhibition and a website. works to Southwark Park. A number of activities have taken place, such as It was a major moment in the life of one of London's guided walks, talks, oral history training and school-based oldest parks, so we held a party, sung some songs, had a projects. On the way we have developed partnerships with drink or two, and published a small booklet to mark the several local organisations and community groups. occasion. In summer 2009 we had some more drinks, As you can see we have drawn heavily upon the sung some more songs, and published another, slightly memories and opinions of people in Bermondsey and larger booklet, this time to herald the park's 140th Rotherhithe to make the book as rich as possible. anniversary. We thank everybody who agreed to take part, and also the Curiously, in looking back through the archives, we could Heritage Lottery Fund and Southwark Council's Parks find no record of any previous anniversary celebrations; Service for their help and encouragement. -

Alfred Salter Weekly

Alfred Salter Weekly 18th June 2021 News from Alfred Salter Primary School Headteacher’s Message pick the winner and took us a while to make a We have had a fantastic week this week! It decision. Well done to everyone who entered and has been very busy and there has been lots congratulations to the following pupils: of exciting learning, activities and events. First Prize: Eowyn, Reception Design and Technology (D&T) week was a triumph; Runners up: Ashley, Year 5 and Elizabeth, Year thank you to Louisa Ogborne, D&T Lead for 4. organising a great event. We also celebrated what Eowyn won a very special chef’s hat and apron and would have been Alfred Salter’s birthday on Ashley and Elizbeth both took home an inventor’s Wednesday with a focus on the humanitarian work handbook. The posters are proudly displayed all that he and his wife Ada Salter spent many years around the school. Photos from D&T week can be working on. Next week is Sports Day(s), details of seen on the last page. which can be found further down this Newsletter. We look forward to seeing as many parents and Alfred Salter’s Birthday th carers that can attend. It has been a very long time Wednesday 16 June would have been th since we have been able to safely invite parents and Alfred Salter’s 148 Birthday. This year, carers into the school, and I would like to remind you we focussed on the passion that both he that, to ensure the safety of the whole school and his wife Ada had for humanitarian work and the community, social distancing will be in place and love they showed for their local community.